Art and Culture

The Age When Nothing Fits

‘Rebel Without a Cause’ remains a landmark classic, seventy years after its release.

The teen film has become so ubiquitous in recent years that it’s easy to forget it is still a relatively modern phenomenon. The word “teenager” only became part of the general lexicon in the early 1900s, and it took several decades for American cultural marketeers to work out that they could capitalise on this untapped demographic. American filmmakers virtually ignored adolescents until the middle of the 20th century, both in cinematic depictions and as a potential audience. As far as Hollywood was concerned, children were children until they were not, so the appearance of adolescent characters on screen was rare and usually unimportant.

The early Mary Pickford and Lillian Gish silent film vehicles were among the first adolescents portrayed in cinema, mostly as sweet Pollyanna ingénues and damsels in distress. Later, Joan Crawford in Our Dancing Daughters (1928), Mickey Rooney’s Andy Hardy series (1937–46), and Shirley Temple in The Bachelor and the Bobby Soxer (1947) were perky teens whose most pressing concerns were falling in love and getting married, thereby conforming to parental expectations. When other teen concerns were finally explored in a serious way during Hollywood’s early decades, it was usually in stirring patriotic war films like All Quiet on the Western Front (1930).

Even today, most teen films fall into the comedy and/or romance genres and are often dismissed as frivolous or formulaic. Not many films were prepared to treat adolescent angst seriously, even during the 1980s and ’90s heyday of teen cinema. This is why Nicholas Ray’s 1955 film Rebel Without a Cause remains a landmark classic, seventy years after its release. Although it was not the first film to explore young people’s discontent and alienation, it is still one of the best and most influential. In many ways, it was the prototype of this subgenre of cinema—a timeless and subversive story tucked within a conventional Hollywood narrative structure.

Rebel Without a Cause was released during a socially conservative era. Although the postwar boom saw America’s middle class comfortably ensconced in leafy suburbia, discontent and paranoia stirred beneath the idyllic facade. Reports of teen violence bewildered and terrified parents, who were led to believe that rock ’n roll was responsible for antisocial behaviour. In September 1954, a year before the premiere of Rebel Without a Cause, a Newsweek article appeared under the alarmist headline, “Our Vicious Young Hoodlums: Is There Any Hope?”

Hollywood studios were eager to exploit this new cultural phenomenon and the intergenerational conflict it seemed to be producing. Their cynicism is evident in the various taglines Warner Brothers used to publicise Rebel Without a Cause: “Teenage terror torn from today’s headlines!” splashed one alliterative poster. “And they both come from good families!” warned another. “Jim Stark... a kid from a good family—what makes him tick... like a bomb?” Hyperbole and sensationalism of this kind were partly designed to lure audiences back to the cinema at a time when the new technology of television was eating into movie-studio profits. But they also catered to the growing fear and anxiety many adults felt about the younger generation.

The title of Ray’s film was lifted from a book by psychiatrist Robert M. Lindner titled Rebel Without a Cause: The Hypnoanalysis of a Criminal Psychopath, first published in 1944. Lindner had already attempted to adapt his own bestseller for the screen, but without success. It was not until Ray, who had a difficult relationship with his own teenage son, wrote a seventeen-page treatment based on Lindner’s book that the project gained any traction within the studio system. Ray had previously dabbled in themes of juvenile criminality in his film noir They Live By Night (1948), and in the social-consciousness picture Knock on Any Door (1949), which coined the phrase “Live fast, die young, and leave a good-looking corpse.”

Ray turned his treatment over to several different screenwriters, but then rejected the scripts they submitted for being too clichéd. He wanted something gritty, realistic, and immediate and he was willing to wait for the right collaborator. When screenwriter Stewart Stern came on board, he began by researching the new phenomenon of “chicken runs”—dangerous car races in which newly licensed teenagers tempted death at high speeds. Stern also spent some time observing social workers at the Los Angeles Juvenile Division before turning in a screenplay that met with Ray’s approval and obtained a green light from Warner Brothers.

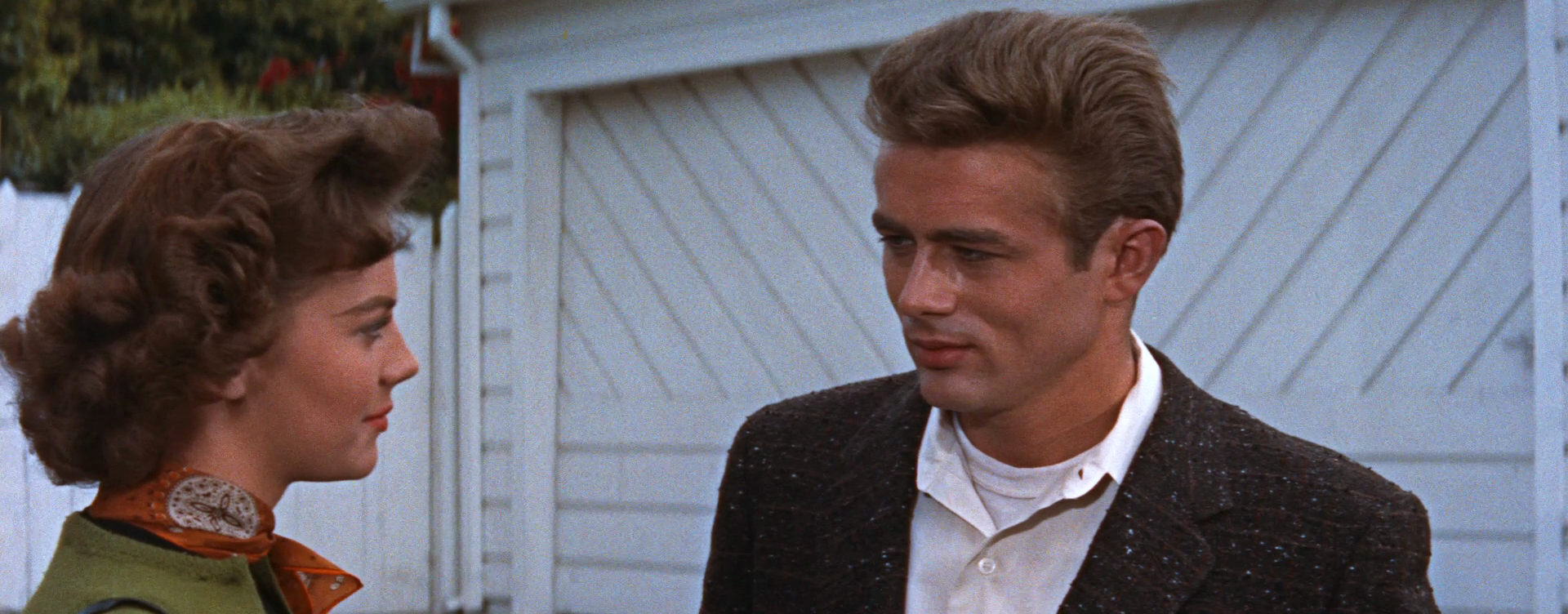

James Dean was cast in the soon-to-be iconic role of Jim Stark—the troublesome new kid in town trying to navigate the social hierarchies of his high school. On his first day, Jim is dismissed by his neighbour Judy (Natalie Wood) as “a new disease,” but he manages to befriend another social outcast named Plato (Sal Mineo) who begins to worship him. During a class excursion to LA’s Griffith Observatory planetarium, Jim is provoked by a local gang led by Judy’s boyfriend, Buzz (Corey Allen). Jim is challenged by Buzz to a “chickie run”—the young men will race their cars towards a cliff edge and see who is the first to jump out. In a development subsequently copied for the 1984 teen film Footloose (albeit with tractors!), Buzz’s jacket gets stuck, preventing him from leaping from his car, and he plunges over the cliff to his death.

To cope with his guilt, Jim befriends Judy and heads to an abandoned mansion with Plato in tow to hide from Buzz’s vengeful gang. The three play house with Jim and Judy taking on the role of pseudo-parents mocking young people as “noisy,” “troublesome,” and “annoying.” They are initially unaware that Plato has brought his father’s gun along to protect himself. When Plato runs and hides at the Griffith Observatory, a misunderstanding with police leads to him being shot to death in front of Jim and Judy.

The action in Stern’s screenplay plays out over 24 hours. According to Live Fast, Die Young, an exhaustive account of the movie’s production by film historians Lawrence Frascella and Al Weisel, Stern said this “crazy compactness” was intended to capture a sense “typical of young people who are running away from boredom and who are running away from themselves. Their days are stuffed with such incredible drama, and it’s a drama going on under the noses of the parents who don’t in the least suspect that it’s happening.”

The parents in Rebel Without a Cause are generally oblivious or absent. Jim’s emasculated and bewildered father (Jim Backus) does his best to understand his son: “We give you love and affection, don’t we? Well, then, what is it?” he asks Jim at one point. Jim’s mother (Ann Doran) is much less sympathetic, more concerned with her reputation and the perception of others than she is with her son’s happiness. “You pray for your children. You read about things happening to other families, but you never dream it could happen to yours,” she complains.

However, parental struggles are not the film’s focus or subject. Nicholas Ray made Rebel Without a Cause in an earnest attempt to understand young people and their struggles. Ignoring studio attempts to interfere, he cast every role himself and workshopped the script for several weeks with his young cast until he was ready to shoot. This attention to detail produced heartbreaking performances from his three leading actors that still resonate seventy years later. In The Wild One (1953), an even earlier film about alienated youth from which Ray drew inspiration, Marlon Brando is asked what he is rebelling against. “Whaddaya got?” he replies. Jim, Judy, and Plato are less cryptic. Although the title of Ray’s film suggests that teenagers act out for no reason, his characters make it clear that they believe their parents’ lack of understanding is the cause of their anguish.

We meet all three protagonists in the film’s opening scenes when they are each brought into a police station for questioning late at night. Jim has been detained on a drunk and disorderly charge. Judy has been apprehended for walking the streets late at night, and gives a tearful story of her father rubbing off her lipstick and calling her “a dirty tramp.” Plato has shot some puppies while his mother is away on holidays—his father has not been seen in years—so the family maid has to collect him from custody. Although they do not speak, each is aware of the others’ presence. As Jim leaves the police station, he expresses his confusion to one of the police officers: “If I had one day when I didn’t have to be all confused and ashamed of everything… or I felt I belonged some place.”

Despite occasional lapses into hokey romance and melodrama, the film is fraught with the threat of danger, violence, and death. The origins of teenage criminality, it is implied, arise from a combination of boredom, peer pressure, frustration, and misdirected desire. The opening credits are rendered in a blood-red typeface, and the colour becomes a recurring motif also found in Dean’s iconic jacket, and in Wood’s coat and lipstick. (Principal photography actually began in black and white, but the studio insisted on switching to colour when the release of East of Eden made James Dean a star.)

Ray later explained that the use of red was “a warning.” Frascella and Weisel call it a symbol of teenage passion, “the anger of adolescence, the audacity of rebellion, the threat of blood and violence as well as a definite sexual bravado.” It complements what they call Ray’s “visual turbulence” and the theme of internal turmoil. All three protagonists are guilty of teenage histrionics, but they are also flirting dangerously with self-destruction. “I don’t know what to do anymore,” Jim says at one point, “except maybe die.”

If gossip columnists and trashy biopics are to be believed, James Dean, Sal Mineo, and Nicholas Ray were all either gay or bisexual. Although all references to homosexuality were coded to avoid the censors, the actors played up the homoeroticism implied by Stern’s script.

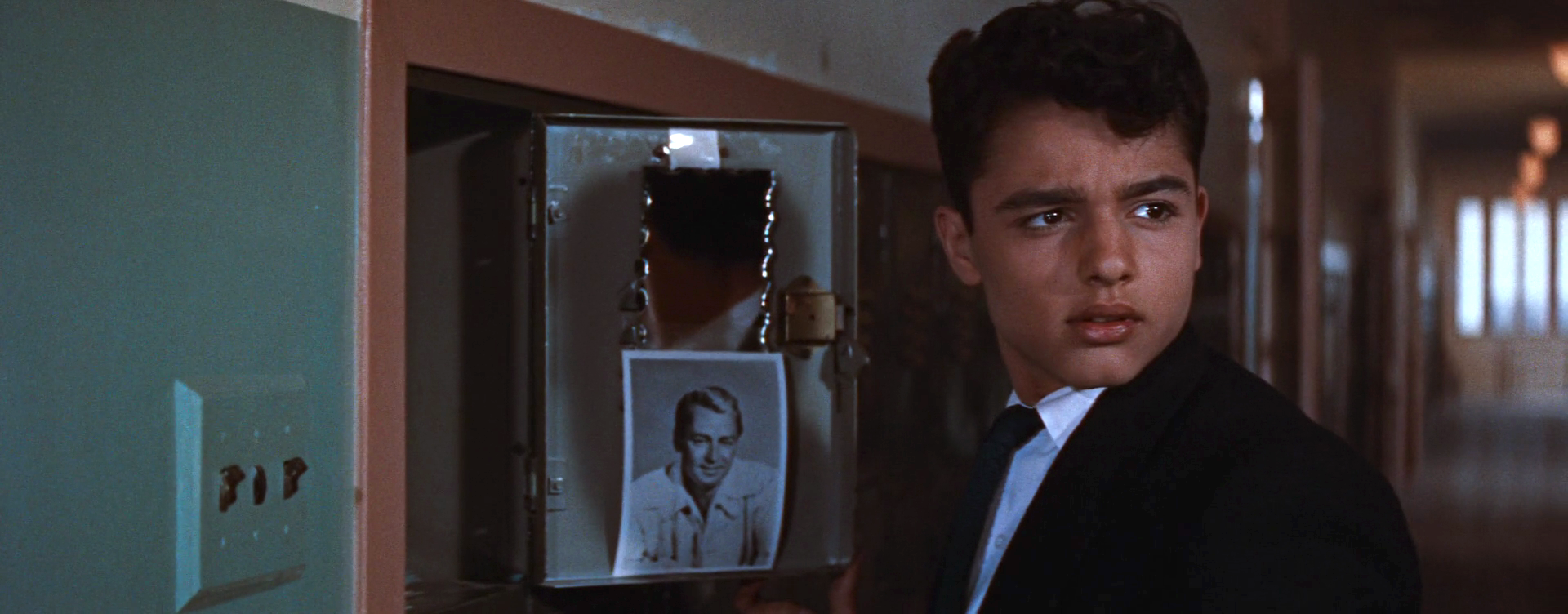

Plato’s adoration of Jim betrays a yearning seldom depicted in Hollywood film. Years later, Mineo maintained that Plato was “the first gay teenager in films.” Although Plato’s real name is revealed to be John, he adopts the name of the gay Greek philosopher, rides a Vespa, and keeps a photograph of film star Alan Ladd in his school locker—all of which is mocked by his peers. His loneliness is alleviated by Jim’s arrival in town, and he brags to Judy that Jim (who he’s only just met) is now his “best friend.” When the boys are alone, Plato asks Jim, “Hey, you want to come home with me? I mean, there’s nobody home at my house, and heck, I’m not tired.”

Although Jim and Judy will eventually wind up together, Jim responds to the younger boy’s infatuation with empathy and understanding. Dean only made three films during his short life (East of Eden and Rebel Without a Cause were both released in 1955 and Giant followed in 1956), but he managed to cultivate a screen persona that appealed to men and women alike. He could be tough, charming, and assertive, but he was still able to subvert gender norms. “[Dean] certainly altered the image of maleness on screen,” write Frascella and Weisel. “[H]e was not afraid to show fragility that might be characterised by some at the time as feminine. He was not afraid to cry on screen and his desire to seduce anyone who locked into his gaze knew no gender boundary.” When they were rehearsing their scenes together, Dean is said to have told Mineo to “look at me the way I look at Natalie.” Mineo later revealed that “it was only years later that I understood I was incredibly in love with him.”

Rebel Without a Cause rejects machismo for male sensitivity and tenderness. Its most intimate scenes are reserved for the conversations involving the male characters: between Jim and Plato as their friendship develops, and between Jim and his father as they try to connect and understand one another. Even Jim’s feelings for Judy are chaste rather than carnal in nature—as Stern’s screenplay explains, Jim “wants to find a girl who will be willing to receive his tenderness.”

Ray’s complex portrayal of Judy’s sexuality—a product of unrealistic social expectations imposed on female conduct—was also unusual and daring for the time. According to Rebecca Sullivan’s excellent 2016 biography of Natalie Wood, Judy is “a girl on the precipice of an adolescent rebellion defined almost exclusively by confusion between love and lust, first for her father then for the father-figure lover, Jimmy. Sex would simultaneously be her downfall and her redemption.” She is scolded by her father when she attempts to give him a greeting kiss: “Girls your age don’t do that,” he snaps. “Girls don’t love their fathers?” she replies. “Since when? Since I got to be sixteen?” When she tries to kiss him again, he slaps her face and she runs from the house in tears.

Rebel Without a Cause was a breakout role for Natalie Wood, then a sixteen-year-old former child star. It proved, Sullivan remarks, that she “could be believable as both a virginal sweetheart and a promiscuous rebel.” In 1961, Wood appeared in Elia Kazan’s Splendor in the Grass as a young woman grappling with her bourgeoning sexuality, fearful that accusations of promiscuity would ruin her reputation. “These scenes shed light on the postwar cinematic tropes of teen-girl sexuality,” Sullivan writes, “which often relied on Electra-infused psychodramas that eventually sort themselves out once the girl finds a young man to whom she can transfer her masochistic need to be dominated by love.” In Rebel Without a Cause, Judy ultimately finds what she is looking for in Jim. In a tight close-up before their first kiss, Judy confesses, “I love somebody. All this time I’ve been looking for someone to love me. And now I love somebody. And it’s so easy.”

Despite its bold exploration of sexuality (particularly during the era of Hayes Code censorship), Rebel Without a Cause finally conforms to the Hollywood convention of appearing to punish characters who stray too far from social norms. Mid-century Hollywood had a habit of killing off sexual deviants and femme fatales, and so it is Plato who is sacrificed in the final minutes of the film, thereby allowing Jim and Judy’s relationship to flourish uncontested. Nevertheless, Sal Mineo’s performance is one of the most sympathetic early representations of homosexuality on screen, and it is one with which young gay viewers can still identify.

The success of Rebel Without a Cause in 1955 was in no small part due to its originality. For the first time, American teenagers were presented with a Hollywood film that spoke about their lives, their frustrations, and their concerns. A serious studio drama took teenage disillusion seriously, and it didn’t patronise them or attempt to sanitise their confusion and pain. Many of them returned to rewatch it multiple times. Rebel Without a Cause also garnered Academy Award nominations for Nicholas Ray (Best Screen Story), Natalie Wood (Best Supporting Actress), and Sal Mineo (Best Supporting Actor). Today, the American Film Institute lists it among the 100 best films of all time and it is archived at the Library of Congress’ Film Registry in acknowledgement of its cultural, historical, and aesthetic importance.

Tragically, all three of the film’s stars died young. James Dean died in a car accident aged 24 on 30 September 1955, just a few weeks before Rebel Without a Cause was released. Sal Mineo was stabbed to death aged 37 during a mugging on 12 February 1976. And Natalie Wood died in a drowning accident on 29 November 1981, aged 43. This has all added to the mystique of the film in general, and to James Dean’s status as an American icon in particular. To this day, Dean’s name is synonymous with teenage rebellion and alienation, and his likeness is used to sell everything from mugs and bobble-heads to posters and clothing. His image has been licensed by Levi’s, Lee, Porsche, Mercedes Benz, and Dolce & Gabbana and his iconic red jacket fetched US$600,000 at an auction in 2018. According to Forbes magazine, Dean is still one of the highest earning dead celebrities.

Rebel Without a Cause was followed by many imitators (most of which are not nearly as good as the film that inspired them). First came a series of trashy low-budget juvenile-delinquent films, followed by a spate of coming-of-age dramas that attempted to recapture Ray’s earnest compassion. These included French New Wave classics like The 400 Blows (1959) and Breathless (1960), and mainstream Hollywood vehicles like Jailhouse Rock (1957), To Sir With Love (1967), Foxes (1980), The Outsiders (1983), The Breakfast Club (1985), Heathers (1989), Pump up the Volume (1990), Donnie Darko (2001), Eighth Grade (2018), and Booksmart (2019), all of which tried to explore adolescent angst with varying degrees of success. The genre is now so familiar that it has its own subgenre of parodies, including films like Cry-Baby (1990), High School High (1996), and Not Another Teen Movie (2001).

Asked why the film still resonates, screenwriter Stewart Stern said it was a “plea for compassion. That’s why kids love it … everything that people condemn in us as some kind of nefarious behaviour—experimental behaviour, dangerous behaviour—is absolutely pure, sweet, innocent reaching out.” After the lethal Chickie Run, Jim reaches out to Judy and she slowly lifts her arm to place her hand in his. Seventy years later, that tenderness is still being felt by misunderstood teenagers everywhere.