Israel

A Cartoonish View of History

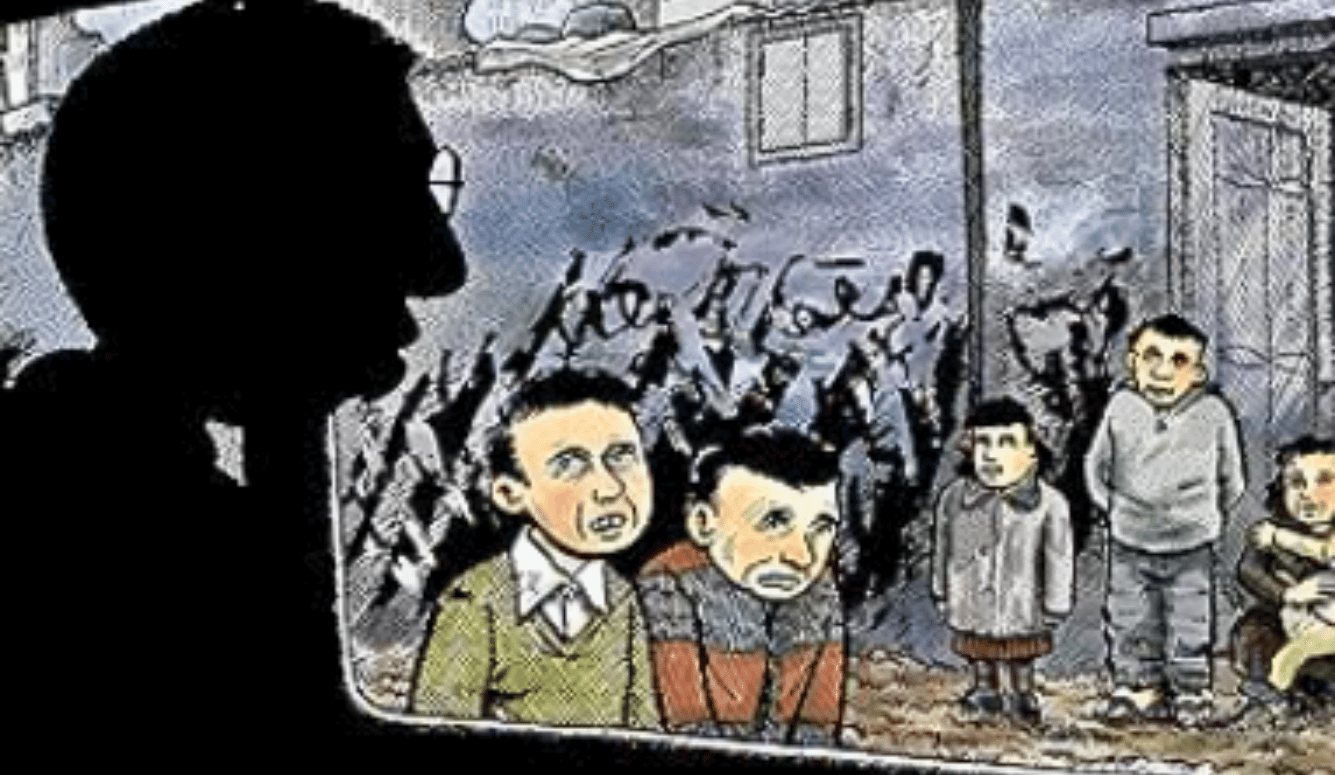

Joe Sacco’s graphic works provide vivid and moving depictions of the terrible suffering in the Strip. But his accounts of the causes of that suffering are simplistic and one-sided in the extreme.

A review of Joe Sacco’s books Palestine, 296 pages, Jonathan Cape (January 2003); Footnotes in Gaza, 432 pages, Metropolitan Books (October 2010); and War on Gaza, 32 pages, Fantagraphics (December 2024).

In April 2024, prominent French Jewish cartoonist Jean Sfar published a graphic novel entitled Nous Vivrons (“We Shall Live”), which dealt with Hamas’s barbarous 7 October 2023 attack on Israel and the worldwide wave of antisemitism it generated, with reference to French Jewry. After receiving death threats from Muslims, he was forced to live under police protection.

On the other hand, Joe Sacco, a prominent American cartoonist/journalist has required no police protection, though he has been publishing cartoons and graphic non-fiction books lambasting Israel’s behaviour towards the Palestinians for years now. In December 2024, he published a 32-page graphic booklet called War on Gaza, in which Israeli atrocities allegedly committed during the current bout of hostilities figure large.

But Malta-born Sacco’s obsession with Gaza—a crowded 141 square mile (365 square kilometre) strip of arable land and sand dunes along the Mediterranean, bordered by Israel, Egypt, and the sea—began two decades earlier. In 2001, he published Palestine, which covered the iniquities of the Israeli occupation of the West Bank, Gaza, and East Jerusalem since 1967 and the First Intifada of 1987–92. His second volume, Footnotes in Gaza, was published in 2009, to great acclaim. According to the New York Times, it constituted “investigative reporting of the highest quality. A gripping, important book.”