Environmentalism

Why We Distrust Technology

Why do so many people reflexively favour social solutions to climate change while discounting the promise of technological breakthroughs? The answer lies in our evolutionary past.

The history of human flourishing is a story of technological progress. From the taming of fire to the Industrial Revolution, our species has found ways to reshape the world, turning scarcity into abundance and hardship into comfort. Yet, when it comes to some of today’s concerns—climate change, food security, deforestation—the instinctive response is rarely technological optimism. Instead, the prevailing narrative emphasises social change: reducing consumption, altering human behaviour, and enforcing collective restraint.

Why do so many people reflexively favour social solutions—carbon taxes, regulations, lifestyle changes—while discounting the promise of technological breakthroughs? The answer lies in our evolutionary past and in the way our minds have been shaped to solve problems. As psychologist William von Hippel has noted, humans evolved for social solutions rather than technological ones. That cognitive legacy continues to influence how we approach modern challenges, often leading us to dismiss the very innovations that could provide scalable, lasting solutions.

For most of our history, human survival depended less on technological ingenuity and more on cooperation and social cohesion. Our ancestors did not invent their way out of problems; they solved them through alliances, negotiations, and collective rulemaking. Food shortages, for instance, were addressed not by developing advanced agricultural techniques—those came much later—but by rationing resources, redistributing wealth within the tribe, and reinforcing norms against hoarding.

This survival strategy shaped our psychology. Over generations, humans became attuned to social fixes as the primary way to navigate crises. We evolved to seek consensus, enforce norms, and reward conformity—traits that helped small groups function efficiently in an unpredictable environment. As a result, when confronted with modern challenges, we instinctively default to social regulation over technological adaptation.

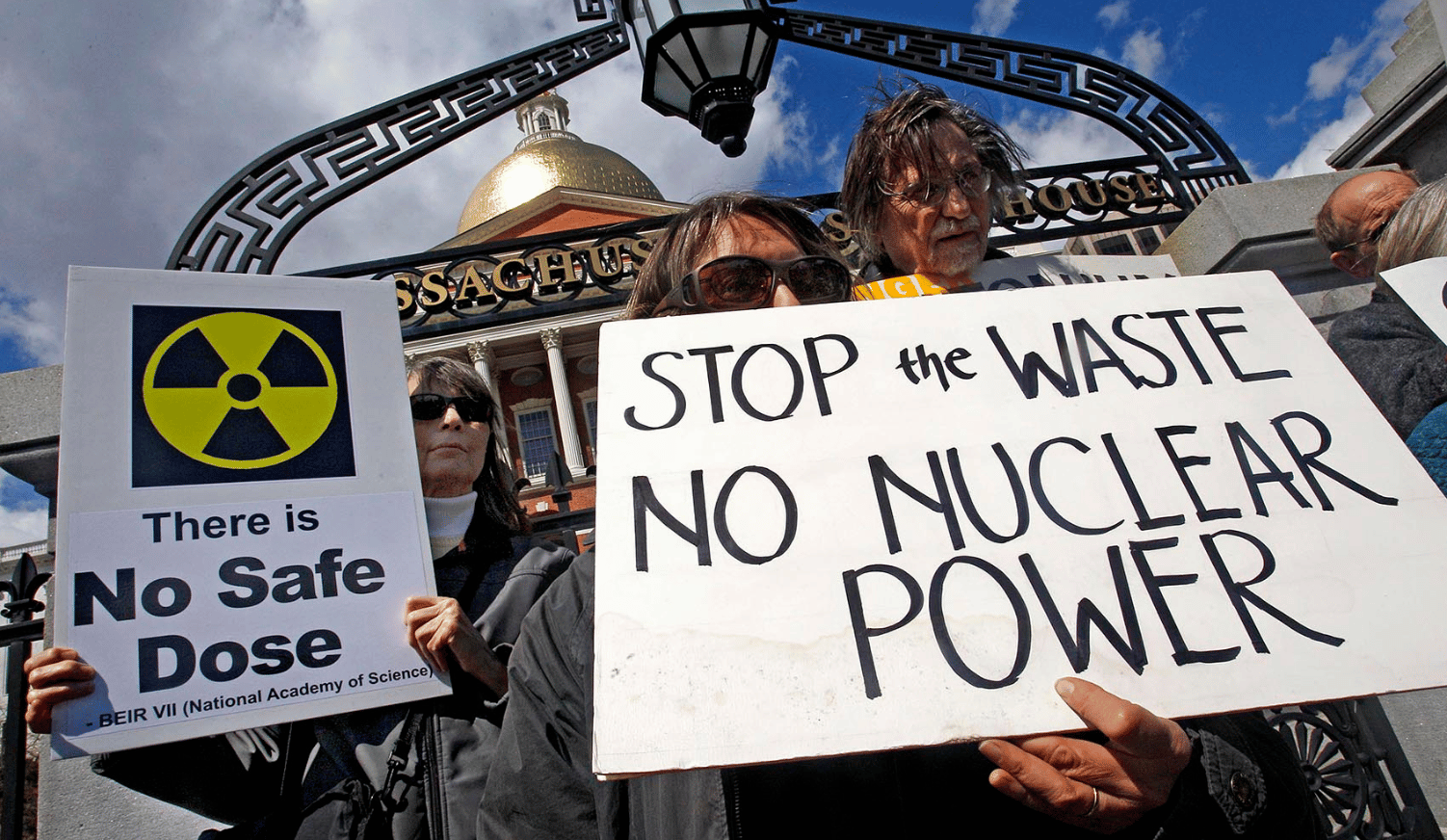

Today, this bias manifests in the way we talk about, for example, climate change. The dominant discourse does not emphasise nuclear fusion, carbon capture, or geoengineering, despite their potential to dramatically cut emissions. Instead, we hear calls for people to consume less, fly less, drive less, eat differently—as though the best way to tackle a global problem is through personal sacrifice. This isn’t a rational economic approach; it’s a deeply ingrained cognitive reflex.

Beyond evolutionary psychology, several well-documented cognitive biases reinforce our scepticism toward technological solutions. One of the most powerful is negativity bias, the tendency to focus more on potential downsides than on possible benefits. Innovations—especially large-scale ones like nuclear power or geoengineering—are often accompanied by uncertainties. A nuclear plant meltdown is a vivid disaster; the slow, cumulative benefits of abundant clean energy are far less emotionally gripping.

Similarly, the availability heuristic skews our perception of risk. When we think about environmental disasters, we can readily picture hurricanes, wildfires, and melting ice caps because they dominate the news cycle. But few can just as easily imagine the gradual improvement of solar efficiency, battery storage, or direct air capture technologies, even though these developments are advancing every year. The more available a mental image is, the more likely we are to see it as relevant. Since climate catastrophes are widely publicised while technological progress happens quietly, we develop a distorted sense of urgency and inevitability.

Then there’s linear thinking, the assumption that current trends will continue indefinitely. If emissions are rising and temperatures are increasing, many assume the trajectory will continue unchecked—unless human behaviour radically changes. What this ignores is the power of nonlinear technological breakthroughs to disrupt trends entirely. Few in 1970 predicted that agricultural innovation would allow us to feed four billion more people than seemed possible at the time. Similarly, few today can conceive of how energy revolutions might render current emissions concerns obsolete.

Another reason technological solutions struggle for mainstream acceptance is that moral frameworks dominate the climate debate. The prevailing rhetoric paints fossil fuel consumption as a sin, framing climate action as an ethical obligation rather than an engineering challenge. The underlying assumption is that suffering is virtuous—that real change requires sacrifice, restraint, and a return to a simpler way of living.

This moral framing naturally privileges social solutions over technological ones. Cutting emissions through sacrifice feels righteous; solving the problem through innovation seems like cheating. But history shows that progress has always come from overcoming limitations, not submitting to them. Fewer people today still argue that the solution to food insecurity is simply to eat less; yet many advocate that the best way to combat climate change is to consume less energy rather than produce it more cleanly.

This view is not only misguided but actively harmful. By demonising industry and technology, we risk stifling the very innovations that could ensure prosperity while reducing environmental impact. We should not ask, “How can we get people to use less energy?” but rather, “How can we produce abundant, clean energy?” We should focus not on curbing human ambition, but on directing it toward better outcomes.

The tendency to discount innovation is not new. Time and again, humanity has misjudged its own capacity for problem-solving. In the nineteenth century, urban planners feared cities would collapse under the burden of horse manure, failing to anticipate the automobile. In the 1960s, experts predicted mass starvation due to overpopulation, not foreseeing the Green Revolution, which vastly increased crop yields.

Even within the energy sector, past environmental concerns have been rendered irrelevant by technology. The deforestation crisis of the nineteenth century—caused by the need for wood as fuel—was solved not by conservation, but by the discovery of coal and oil. Today’s fear that renewables can never scale ignores the potential of next-generation batteries, advanced nuclear, and synthetic fuels to transform the landscape.

If history teaches us anything, it is that human ingenuity consistently outperforms doomsday predictions. That does not mean we should ignore environmental challenges. It means we should approach them with the mindset that has served us best—problem-solving through innovation, not retreat.

Climate change and other environmental concerns can be challenging, but they are not insurmountable. The solution is not to limit prosperity, but to decouple it from environmental harm through better technologies. Energy abundance, clean industry, and new materials are the future—not austerity, restriction, and economic regression.

Recognising the psychological roots of our bias against technological solutions is the first step toward overcoming it. The next step is to embrace a rational optimism—one that acknowledges risk while also investing in the solutions that history shows will prevail. The world has never been saved by fear, but it has been saved—again and again—by human ingenuity.