Astronomy

Too Many Moons

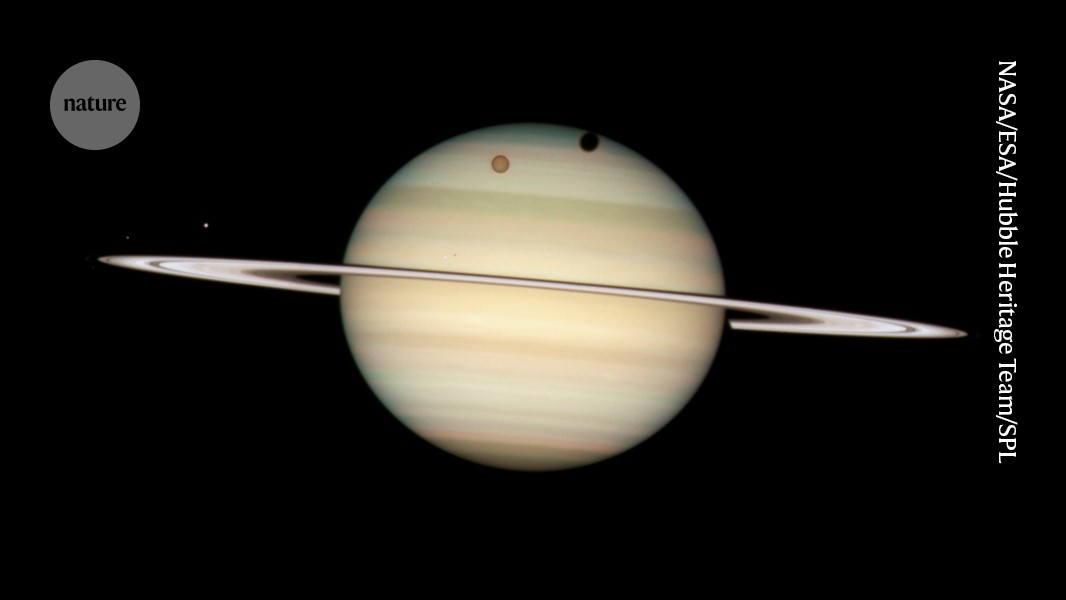

This week’s announcement that Saturn has 274 officially recognised ‘moons’ raises the question of whether that word needs a more restrictive definition.

When my daughter was in grade four, she was instructed to write about a planet of her choice. She chose Pluto. Alas, about fifteen years later, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) decided Pluto was no longer a full-fledged planet—partly because it’s just one of a number of similarly sized objects in an area of our solar system called the Kuiper Belt.

A newly drafted definition of the word “planet” limited the category to celestial bodies that (a) orbit around the Sun, (b) have sufficient mass so as to pull themselves into a nearly round shape, and (c) have “cleared the neighbourhood” around their orbits. Pluto failed the third criterion, and so became a mere “dwarf planet.”

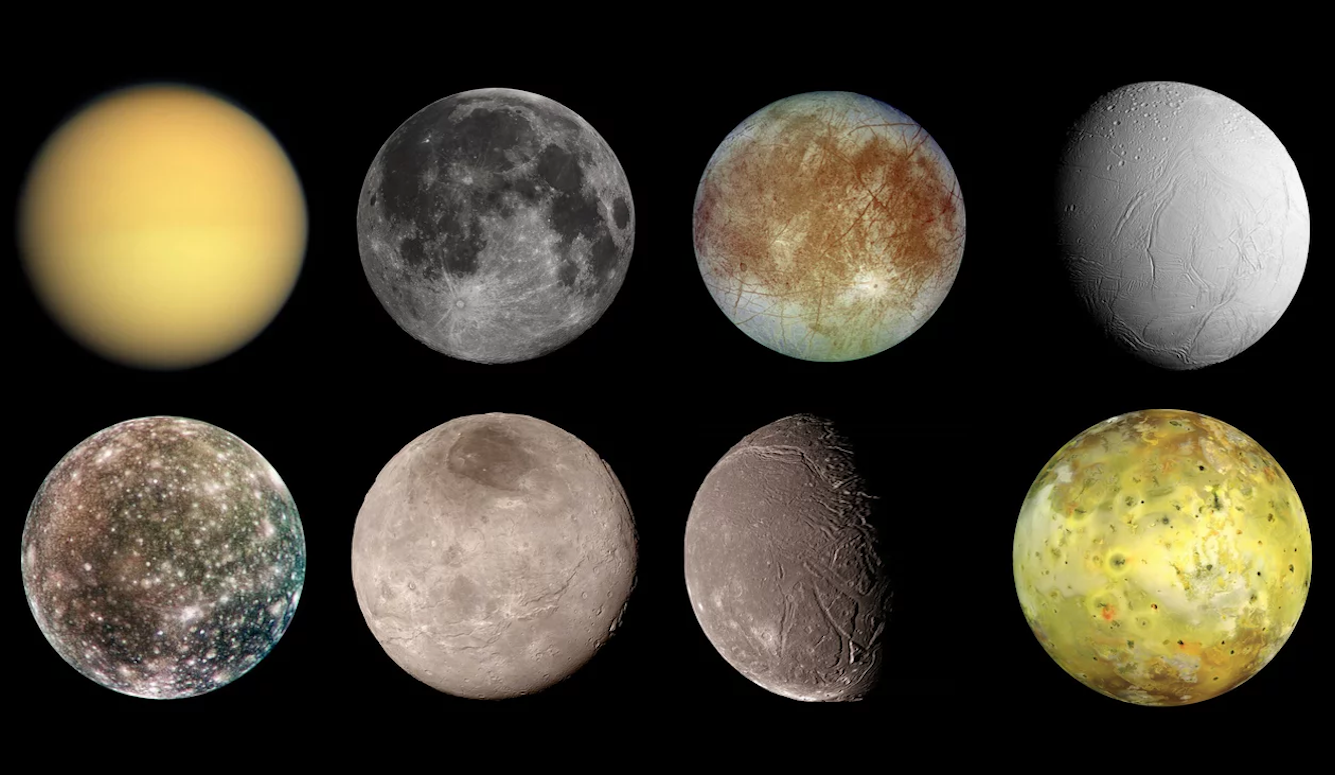

The word “moon” may now be in for similar revisionism: It was announced this week that the International Astronomical Union (IAU) has recognised no fewer than 128 new official moons of Saturn, bringing that planet’s total to 274 known moons. At some point, surely, the word “moon” begins to lose its currency.

When I was growing up, life was simpler. The National Hockey League had six teams, and all the planets had a reasonable number of moons. Jupiter led the way with thirteen (which increased to sixteen in 1979 when the Voyager spacecraft passed by and took a look). At the time, Saturn came close with nine moons, though the Voyager Science Team then added a few more, and so the two gas giants were, for a time, neck and neck.