University Education

Universities Are Worth Saving

Those seeking to address the crisis on America’s campuses should resist the tendency toward nihilism—the temptation to conclude that we need to just (metaphorically) burn it all down.

If you ask most Americans where knowledge comes from, they will probably say: the marketplace of ideas. This is a concept that goes back to English philosopher John Stuart Mill (1806–73) in theoretical terms; and was first enunciated in its modern form by US Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. in his dissent in the 1919 case of Abrams v. United States: “The best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market.”

The marketplace of ideas is a great metaphor. But it turns out to be incomplete for reasons that have to do with the cognitive and social shortcomings of human beings. If you simply put people in a free-speech environment without any rules, guidelines, norms, institutions, or guardrails, you get a cacophony of voices, including trolling, tribalism, rabbit holes, conspiracy theories—in other words, chaos.

In order to create knowledge, on the other hand, you need something that goes beyond Mill and his marketplace. You need James Madison, the father of the US Constitution, and, in my opinion, the greatest political genius who ever lived. In the 1780s, Madison is the key figure, along with George Washington, who understood quickly that the Declaration of Independence was an inadequate basis to run a country.

The Declaration is a grand statement of principles relating to freedom and human equality. What it does not do is establish a structure for governing the independent United States of America. Within only a couple of years, in fact, America’s initial Articles of Confederation dissolved amid the squabbling that broke out among states, which began to inflate their currencies and get into trade wars. As a result, Madison came to understand that you need something more: you need a Constitution.

It turns out that you need exactly the same thing in the world of knowledge that you do in the world of governance: a Constitution of Knowledge. This is not a metaphor, an analogy, a simile, or a figure of speech. It’s an actual thing. You can go and read it.

It’s not in just one place, like the US Constitution, but you’ll find it in places such as the American Association of University Professors’ Redbook, the Code of Ethics developed by the American Society of Newspaper Editors (who now self-describe as News Leaders), and in similar guidelines and protocols developed by other professional, academic, and scientific societies. These are the rules, the norms, and the institutions that structure our public conversations so that they lead us toward truth and away from ignorance, conflict, and oppression.

The key word there is structure. You must have structure for these conversations—or, as famed social psychologist Jonathan Haidt puts it, settings. You need to have the social settings right in order to get the right kinds of conversations and disputations.

As I discuss in my 2021 book, The Constitution of Knowledge: A Defense of Truth, these two constitutions parallel each other—one in the political sphere, one in the epistemic sphere. They are both about settling disagreements, and turning those disagreements into consensus. And they operate on similar principles.

For example, no final say. There’s no last election. There’s no last experiment. The status quo is always subject to change. And that prevents any person or faction from becoming enshrined permanently.

Also, no purely personal authority. The rules are impersonal: Persons are interchangeable, so anyone can vote and gets the same vote. Applying this idea to science: anyone can replicate an experiment, and it better come out the same way. Anything that anyone can do, anyone else can do. No one in particular is in charge. This is the radical principle that underlies both of these systems.

Also, the focus is on consensus, not coercion. Both of these systems rule out the use of brute force, intimidation, bullying, and, of course, violence.

In order to make law, you must compromise. That’s the central idea of the United States Constitution. And in order to make knowledge, you must persuade. You’ve got to get a lot of other people in a community to agree that you’re probably right.

And then, finally, there’s checks and balances. This was Madison’s great inspiration, which, though drawn from Montesquieu, he refined to a great extent.

Ambition is the most powerful force in politics. It’s very difficult to restrain. How do you restrain it? With more ambition: You pit ambition against ambition, yielding a dynamic, energetic system that can be both constrained and creative.

The same principle applies in science. Cognitive researchers have shown that we’re all biased in many ways. And while we can’t see our own biases, you can see some of mine, and I can see some of yours. And if we can pit our biases against each other in a structured way, knowledge can flow from that diversity.

In a room where everyone agrees with everyone else on fundamentals that don’t get questioned, you will not be learning. You will be making mistakes, and you will be unaware of those mistakes.

Seeking knowledge by hunting for errors is the hallmark of the reality-based community. Scientists are professional members of this community. So are journalists in a newsroom—a hub where editors, reporters, fact-checkers, and copy editors gather information, sort through it, try to figure out which of it is valid, and then, if they publish it, pass it on to the global knowledge system through other nodes, applying rigorous rules in the process.

Governments are shot through with institutions that are in the business of anchoring our public policy to reality. Or at least, they should be. A government that isn’t based in facts and reality is ipso facto tyrannical. And if you don’t believe me, ask George Orwell.

There are more components, too—museums, libraries, and even law enforcement. But the single most important part of the reality-based community is the part where professionals advance knowledge for a living. And that’s universities, research centres, journals, and credentialing organisations.

The unique thing about the reality-based community is that it scales. All other systems of knowledge—which tend to be authoritarian schemes based on priests, or princes, or politburos—do not.

The unique thing about the reality-based community is that it scales. All other systems of knowledge, which tend to be authoritarian schemes based on priests, or princes, or politburos, do not scale. One group either predominates and imposes itself, or you get a schism and war.

But the reality-based community is capable of connecting minds and institutions on a global scale—as illustrated by the vast number of organisations that networked to address the COVID pandemic. The number of published research articles on COVID went from zero to over 132,000 in the first sixteen months of the pandemic. This is the result of a global community of researchers—thousands of minds, hundreds of institutions, collaborating in real time. Thanks to their efforts, just a few weeks after COVID was discovered, this network had decoded the genome of the underlying virus. And just a couple of weeks later, they’d designed a vaccine.

There is no other system that can come close to producing knowledge at this scale and at this speed. It’s not an exaggeration to say that every day, the reality-based community creates more new knowledge than all of humanity did in its first 200,000 years of existence.

We take this for granted, but in fact, we should think of it as a species-transforming technology. As individuals or in small tribes, our inherent human capacity to produce knowledge is very low. But once you add this system, you raise by orders of magnitude the knowledge-producing capability of humanity.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that every day, the reality-based community creates more new knowledge than all of humanity did in its first 200,000 years of existence.

What’s more, you put knowledge somewhere different. It’s no longer in our heads. It’s not in the politburo. It’s not in the text of a book such as the Bible. Rather, knowledge has become an emergent phenomenon suffusing a vast hive-like mind that now exists around us. Any of us knows only the smallest fraction of it. Yet all of us participate in building it.

That is what we need to defend: humanity’s greatest accomplishment.

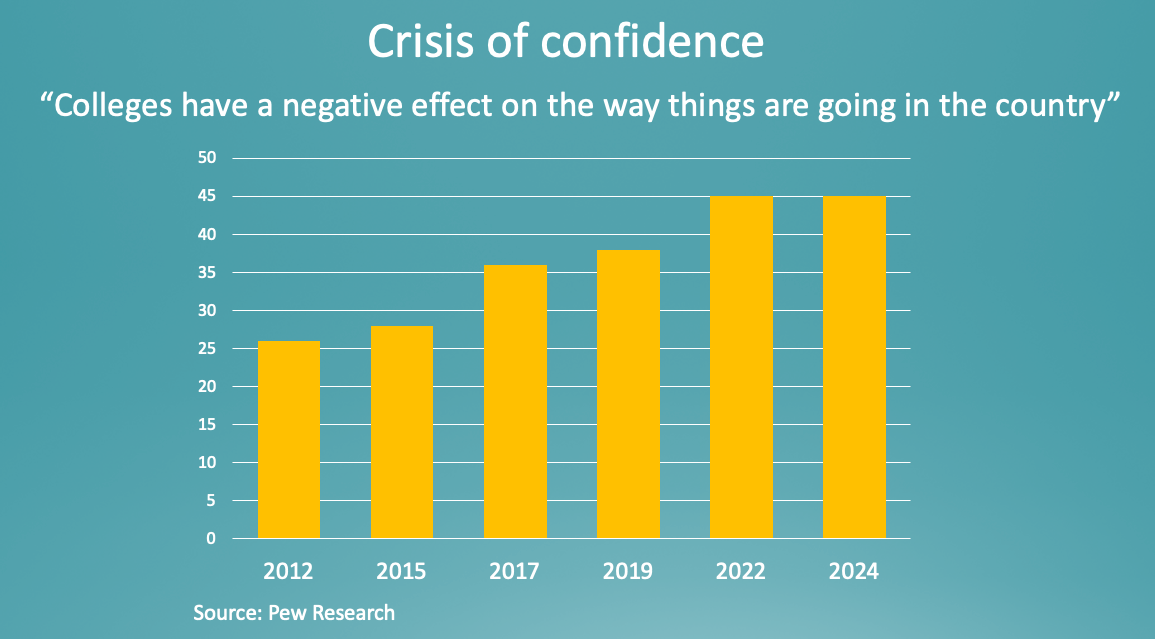

So one might ask: Why does it need defending? By way of answer, consider the data collected by Pew Research when it asked Americans whether they agree with the proposition, “Colleges have a negative effect on the way things are going in the country.” During the decade spanning 2012 and 2022, the percentage expressing agreement went from 26 percent to 45 percent. Almost half of Americans now think that colleges have a negative effect on the country.

That’s a collapse in confidence—one that I believe has been caused by at least six separate factors.

1. IdeologyMany will remember the famous deplatforming of political scientist Charles Murray at Middlebury College in 2017. But what’s less well-known is the unsettling text that students were reading aloud as they blocked Murray from speaking:

Science has always been used to legitimize racism, sexism, classism, transphobia, ableism, and homophobia, all veiled as rational and fact[ual], and supported by the government and state. In this world today, there is little that is true ‘fact.’

This is not new. My first book on the subject, Kindly Inquisitors: The New Attacks on Free Thought (1993), was about the rising ideology that said “fact” is merely a colonialist, sexist construction; and that we should not put stock in the concept of objectivity, as it’s just a power play.

This ideology has seeped in deeply, including a variant that says intellectual inquiry and the very idea of fact endangers the safety of minorities. A 2017 Claremont McKenna College student manifesto, for example, asserted that free speech “has given those who seek to perpetuate systems of domination a platform to project their bigotry.” A Middlebury College student manifesto from the same year argued that free speech “puts [an] undue burden on specific groups of students, asking them to continually defend their right to exist in an academic community for the supposed intellectual enrichment of that same community.” In 2019, the Williams College Coalition Against Racist Education claimed that “an ideology of free-speech absolutism that prioritizes ideas over people, giving ‘deeply offensive’ language a platform at this institution, will inevitably imperil marginalized students.”

2. FragilityAdded to the ideological claim that objectivity and free inquiry are forms of oppression is emotional fragility—some of it real, some of it not so real. But in both cases, there is a sense that if you expose people to ideas that offend them, or which are shocking, or which seem harmful to them, you are committing a form of violent assault.

Many readers will have seen the 2015 footage shot by lawyer Greg Lukianoff in the courtyard of Yale’s Silliman College, in which Professor Nicholas Christakis—then serving as the College’s master—was surrounded by an angry mob of students; and amid all the shouting, one can be heard saying that Christakis’ job is “not about creating an intellectual space… It’s about creating a home.”

This is not a crazy or irrational statement, even if the behaviour on the video makes it seem that way. Universities wear many hats, and among those is that they’re residential communities where people want to feel safe. But the rhetorical move that’s happened here is the expansion of the definition of the word safety to include “safety” from encountering harmful ideas.

Almost all university professors have by now encountered some version of this—the notion that there’s fragility out there, and we all have to be very careful about getting involved in conversations that could hurt and traumatise people emotionally.

3. HomogeneityMany readers will have seen charts that show the political leanings of American professors and how they’ve changed since the Cold War period. As recently as the mid-1990s, the percentage of university faculty members self-reporting centrist political views was only slightly lower than the percentage self-describing as left or liberal; and conservatives still amounted to roughly one fifth of university academics. Then, beginning in the late 1990s, you see a massive shift. And within the space of just two decades, about 60 percent of faculty were on the left, and only about 12 percent were conservative.

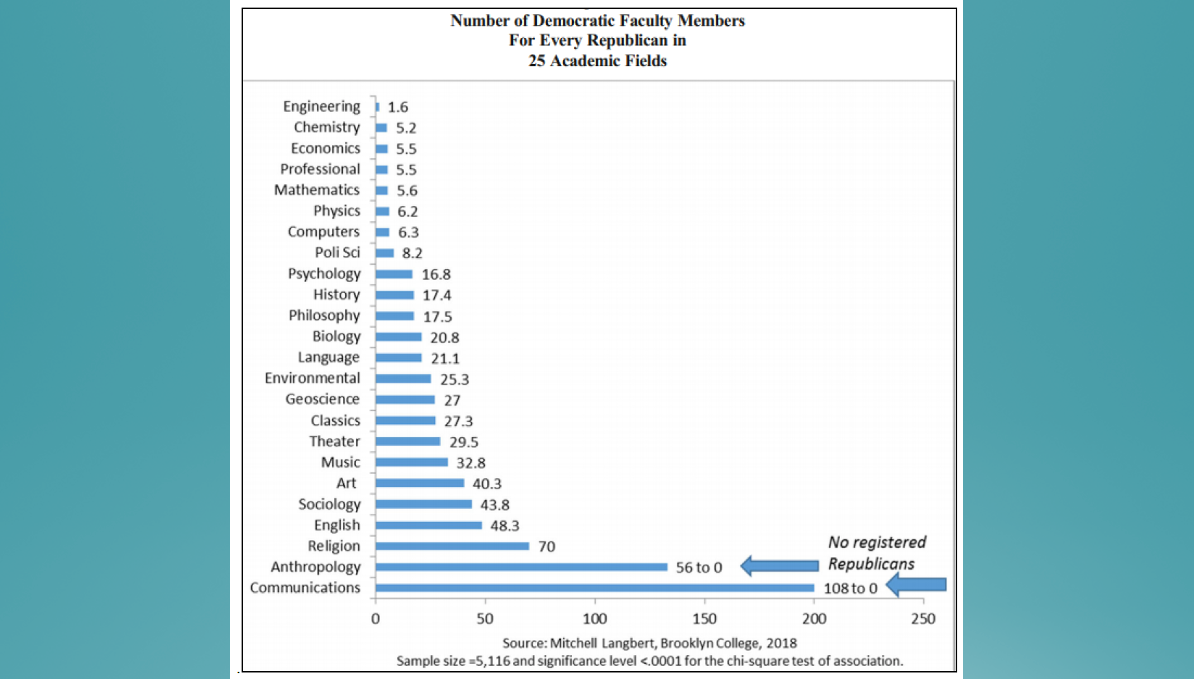

In 2018, Mitchell Langbert of Brooklyn College looked at the Democratic-to-Republican ratios among surveyed university faculty in two dozen academic fields. Only in engineering was the ratio less than five. In almost all of the liberal arts, the ratio was found to be in double digits. In anthropology and communications, the ratio was effectively infinite, as Langbert couldn’t find a single self-identified Republican supporter in either field among his surveyed group (comprising 56 anthropologists and 109 communications specialists).

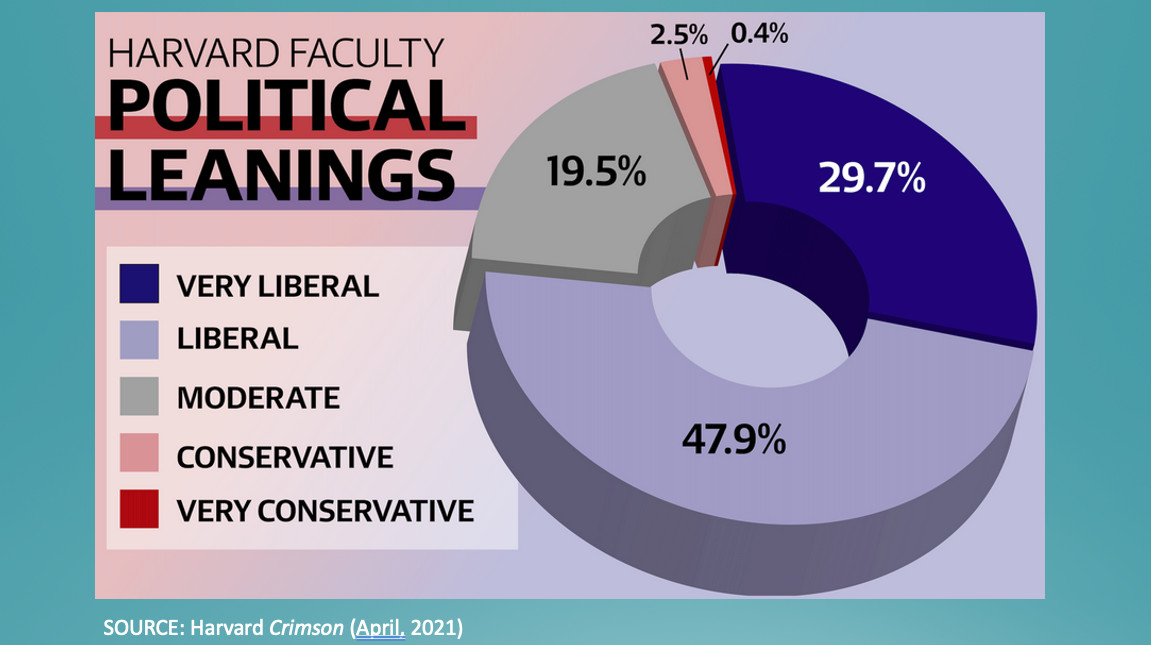

As for Harvard University faculty’s political leanings, a 2021 Harvard Crimson poll found that about 3 percent of participating academics self-reported as conservative; 19.5 percent were “moderate”; and the rest—77.6 percent—described themselves as liberal (about 48 percent) or “very liberal” (about 30 percent). When you’re in a community as politically homogeneous as this, it becomes hard to question orthodoxy and, thus, to do good science.

To quote Nigel Biggar, a British historian of colonialism,

There’s arisen, I think, a certain generation of historians—I can’t say how widespread this view is—that thinks that being activist is where it’s at. And certainly in the UK right now, if you want to get funding, if you want to get promotion, if you want to get a job, then you need to toe a certain political line. And if you don’t, you risk not getting a career at all, not getting funding, not getting promotion. And that’s a recent development. It wasn’t there 10 years ago. So I think that has distorted the process. I know that there are young historians who dissent from this political line. But they voice their dissent at risk of their careers. And I have to say, I hold an older generation of historians responsible, because they’re the ones who allowed this to happen.

And of course, these problems have now crept into the natural sciences as well. In 2022, for instance, Nature Human Behaviour changed its editorial standards to make them overtly political, with editors reserving the right to refuse or retract articles in cases where “people can be harmed indirectly. For example, research may—inadvertently—stigmatize individuals or human groups. It may be discriminatory, racist, sexist, ableist or homophobic.”

The editors also added that “Science has for too long been complicit in perpetuating structural inequalities and discrimination in society. With this guidance, we take a step towards countering this.”

But of course, the job of science and research is to follow the truth. It is not to remedy social injustice.

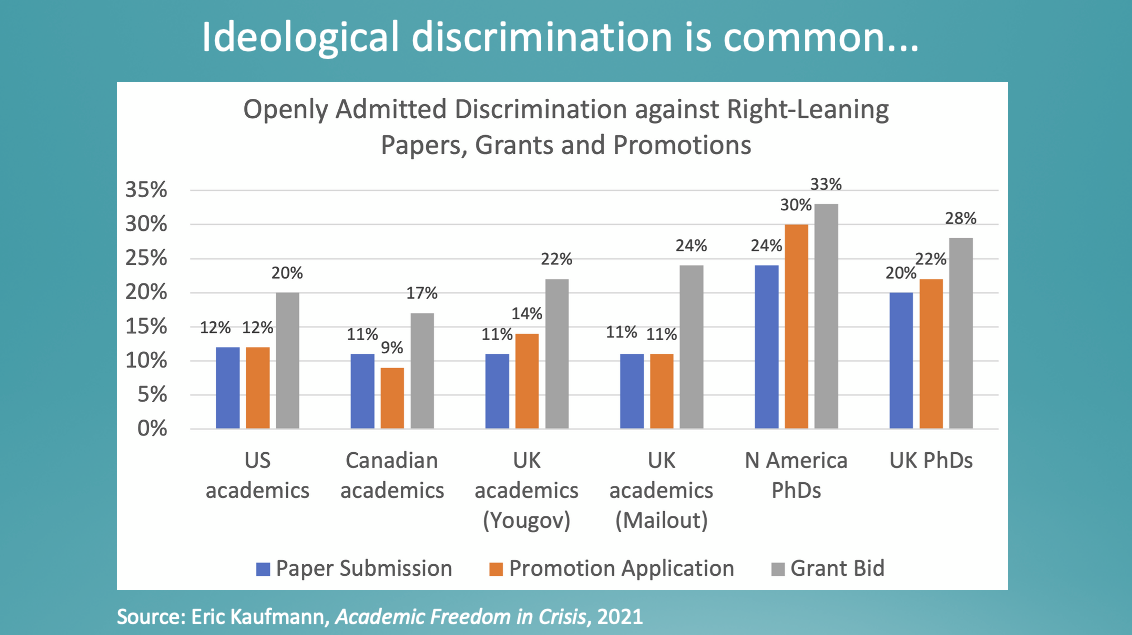

5. DiscriminationConsider survey research published by Eric Kaufmann in 2021. He asked academics in Canada, the United States, and the UK whether they engaged in discrimination against conservatives. In all three countries, a significant number of professors and PhD students reported that they’d discriminated against right-leaning ideas or scholars when evaluating papers, grant applications, and promotions. And remember that Kaufmann’s data, summarised in the chart below, tracks only those academics who admit discriminating. It’s likely that others are discriminating but not willing to admit as much.

The numbers on the right side of the chart correspond to graduate students. In North America, a full third of them are openly admitting they will discriminate against conservatives in grant bids; and a quarter of them in paper submissions. The situation is only a little bit better in the UK. In both cases, we’re talking about the next generation of professors.

Understandably, as Kaufmann’s results demonstrate, conservatives perceive a toxic environment on campus. When asked whether their academic department presented a “hostile climate towards people with your political beliefs,” only 3–5 percent of leftist academics answered in the affirmative. Among conservatives, the corresponding figure was about 70 percent.

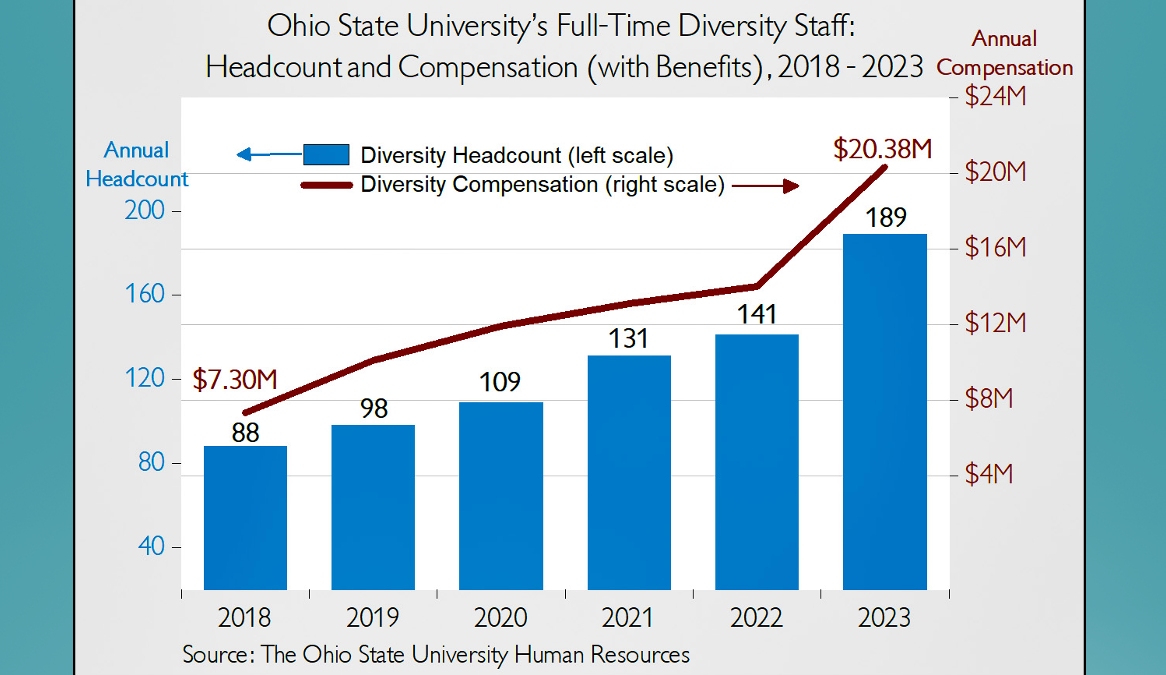

6. BureaucratisationAt Ohio State University, to take one well-known example, there were no fewer than 189 full-time DEI staff as of 2023—up from 88 just five years earlier. And while the head count roughly doubled during that period, the total compensation paid to DEI staffers tripled, to more than US$20-million per year.

There are a lot of issues surrounding the bureaucratisation of higher education, but the one I want to emphasise is that many of these newly hired people aren’t academics by training. They don’t do science. They don’t do research. They may not have ever stepped in a classroom as a teacher. Yet at many universities, these are now the people who are telling tenured professors what to do and how to do it—whether in or out of the classroom. I’ve spoken to tenured and distinguished professors who’ve been called in for four-hour inquisitions at the hands of mid-level HR and DEI bureaucrats in regard to their classroom behaviours, simply because some student somewhere complained about them.

And it doesn’t always matter if these processes end with formal sanctions. In many cases, the investigation is the punishment. And the more DEI bureaucrats get hired, the more reports and investigations are going to ensue.

When you put those six factors together, and then allow them to reinforce each other, the result is to distort and chill academic life. This explains why about 60 percent of American university students surveyed in a 2024 Knight Foundation-Ipsos study expressed agreement with the statement, “The climate at my school prevents some people from saying things they believe, because others might find it offensive,” Now, this is roughly the same percentage of Americans overall who say that the political climate prevents them from saying things they believe. So clearly, this is a national problem. But universities are supposed to be different: They’re supposed to be the one place that’s dedicated to the robust exchange of views.

Even before the 2024 election of Donald Trump, conservative state governments were launching political interventions into the intellectual life of universities, passing laws that directly regulate what can be said and done by academics.

And yet what’s even more concerning to me is the inevitable backlash that’s taken form as this crisis of confidence overwhelms universities. The public has turned hostile, and so has the political system. Even before the 2024 election of Donald Trump, conservative state governments were launching political interventions into the intellectual life of universities, passing laws that directly regulate what can be said and done by academics.

These laws come in different forms, and some are worse than others. The very worst is probably the Stop WOKE Act championed by Florida Governor Ron DeSantis in 2022 (or, more formally, the “Stop the Wrongs to Our Kids and Employees Act”). Fortunately, the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) successfully challenged the law in court, on the basis that some of its key provisions unconstitutionally chill free expression and impose a regime of faculty censorship. But this is a national trend, and it’s not going to stop—especially now that Trump is back in office.

The solution to the problems I’ve been describing won’t come through legislation, but rather through a renewed commitment to liberalism—which provides us with systems that are open-ended, rule-based, and pluralistic. It’s the great idea of John Locke, Immanuel Kant, America’s Founding Fathers, and Alexis de Tocqueville, among others.

And in the liberal spirit, I would urge that those of us seeking to address the crisis on America’s campuses resist the tendency toward nihilism—the temptation to simply rant about how awful and corrupt academia has become, or to conclude that we need to just (metaphorically) burn it all down.

There remain immense reservoirs of integrity in our academic environments. And we must strive to remember that, even in their current form, these environments still constitute the crown jewel of the entire intellectual system produced by our species. They are worth saving—and they can be saved.

This essay was adapted from a keynote lecture delivered by the author at Censorship in the Sciences: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, a conference hosted by the Center for Economic and Social Research at the University of Southern California’s Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences in Los Angeles.