Science / Tech

The Great Divergence

Many psychological and behavioural gaps between men and women have widened in more gender-equal countries, dealing a major blow to sociological theories of sex differences.

As women’s social, occupational, and political engagement expanded in Western nations, social scientists anticipated a great psychological and behavioural convergence of men and women. As Alice Eagly and colleagues wrote, “The demise of many sex differences with increasing gender equality is a prediction of social role theory.” Their perspective is that most sex differences result from adherence to socially imposed norms and expectations. These norms and expectations have changed over the past several generations, as women entered educational, occupational, and political spheres that had been historically dominated by men. Today, in most highly developed nations, women are now the majority in higher education and are on track to become the majority in some formerly male-dominated and high-status professions, such as medicine. Even if one might argue that the gains in gender equality are not complete, social-role theory tells us that we should therefore see the sexes acting and thinking more similarly.

But like many almost-utopian academic predictions, social role and related theories have hit the wall of reality. Instead of convergence of the sexes, we have something closer to a great divergence. To the surprise and dismay of social scientists, many psychological and behavioural sex differences are larger in more gender-equal countries—precisely the opposite of their predictions—which has dealt a major blow to the plausibility of sociological theories of the origin of sex differences. As reviewed by David Schmidt and colleagues, then Marco Balducci, and most recently, Agneta Herlitz and colleagues, the divergence is broad and deep, including aspects of personality, emotional expressiveness, mental health, cognition, and occupational choices and preferences, among others. To be sure, there has been convergence in some areas (for example, intimate partner violence) and no change in others, but the trend is clear—women and men are becoming more different in important ways. Many of the expanding differences are small to moderate for individual traits, but the tableau created is of a substantive divergence.

Expanding liberal mores and a greater range of social and occupational niches enable a fuller expression of individual and sex differences in personality and preferences, among other traits. We are therefore better able to see the true magnitude of innate differences between the sexes in thinking, behaving, and choosing. By analogy, in the US in the 1960s, most families seemed to be similarly entranced by the Ed Sullivan show. But this convergence in viewing habits was driven by a lack of alternatives (there were just three television stations to choose from) rather than a lack of differences between households in their underlying interests. We can see these individual differences better today now that there are hundreds of viewing options available through cable television, streaming, and online entertainment.

One counterargument proposed to explain the great divergence is that more egalitarian societies have stronger gender stereotypes and that these are driving at least some of this divergence. This is a last-ditch attempt to rescue social roles and other blank-slate theories as explanations of sex differences. The problem is that there is a kernel of truth to many stereotypes, so stronger stereotypes could just as easily arise from, instead of causing, larger sex differences in gender-equal countries.

Not Only Society but Also Biology

It’s not just an expansion of options and a loosening of social mores that undergirds the great divergence. Some of the expanding sex differences are likely driven by biological changes. These changes are not down to evolutionary selection but rather a fuller expression of already-evolved sex differences, with this fuller expression occurring in individuals who grew up and live in more favourable environments—put simply, adequate calories and nutrition, low levels of disease, and low levels of social stress.

This pattern follows from Darwin’s theory of sexual selection, that is, competition with members of the same sex for potential mates and discriminating mate choices (female choice of male partners). These dynamics result in the evolutionary amplification in one sex or the other of the physical (e.g., larger size), behavioural (e.g., courtship displays), or cognitive (e.g., birdsong) traits that facilitate competition and choice. The exaggerated nature of such traits makes them more costly to build and maintain, which in turn makes them effective and honest indicators of the bearer’s condition and physical health. By analogy, building and keeping warm a 200-square-metre house is more costly than for a 100-square-metre house and any resource deficits will more strongly compromise the bigger property—in winter, if money and heating oil run short, the larger home will be the colder one.

The key idea is that many biologically based sex differences are greatest under environmentally good conditions, while these traits are less different between the sexes if conditions are or were poorer during childhood and adolescence. This prediction is based on mating competition but holds for any traits that are more impressive in one sex than the other, including behavioural and cognitive characteristics. It has been known for a while that the environment can influence the development and expression of evolved traits, but it is only very recently that this approach has been applied to human sex differences. We and other researchers are on the case, and the findings so far are compelling.

Height provides a clearcut, incontrovertible example of how favourable environments affect sex differences in our biology. As dating apps amply demonstrate, women are attracted to taller and heavier, muscular men. So, in the dating game, taller and stronger-looking men have an advantage, gaining more attention from the fairer sex, as well as being more formidable in the eyes of would-be competitors. This explains why, consistently across societies, on average men are substantially taller and heavier than women—they’ve evolved to be by the process of sexual selection.

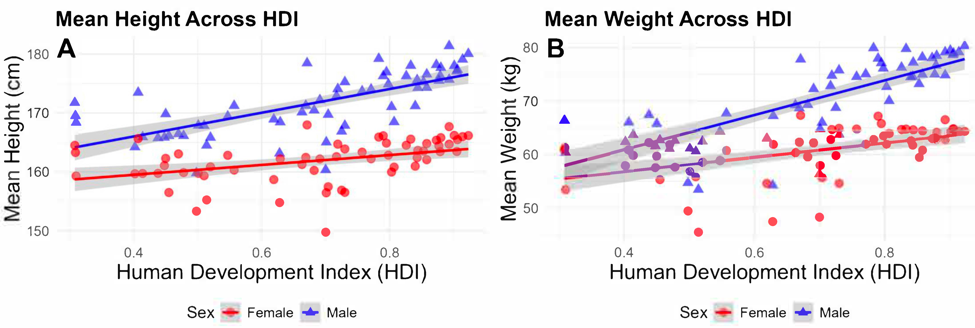

Along with David Giofrè, we analysed the relation between environmental conditions and sex differences in height and weight. First, using the Human Development Index (HDI), we showed that people living in countries with high levels of infectious disease, chronic poor nutrition, and larger overall disease burden (low HDI) are shorter and lighter than individuals living in healthier contexts. The figure below suggests that, as living conditions improve, men gain twice as much in height and weight as women, resulting in larger sex differences in favourable contexts.

It could be that populations that vary in HDI metrics just naturally differ in height, but the same pattern is found within countries across people growing up in better or poorer conditions and across generations as countries become wealthier. For people born before 1905 in the United Kingdom, the average height of men and women was 170 and 159 centimetres, respectively; for people born in 1958, the equivalent heights were 177 and 162. To put this in perspective, about eight percent of women born in 1905 were taller than the average man born in the same year, but this dropped to less than two percent of women for those born in 1958.

From Morphology to Psychology

It’s not just our physicality that is diverging. At least some of the recent psychological and behavioural divergence between men and women is probably influenced by the same factors that have caused a divergence in height. Women typically have an advantage in episodic memory (memory for personal experiences), and Martin Asperholm and colleagues showed that this female advantage was largest for people living in the most economically developed nations, especially for verbal memory. Richard Lippa and colleagues found that men’s advantage in certain spatial abilities (e.g., mentally rotating an image) was largest in countries where citizens had the longest life expectancy which, not coincidentally, is associated with taller and healthier populations.

One of us (Geary) identified fifteen studies of the spatial abilities of US adolescents born between 1929 and 2005—a timeframe in which heights were still increasing—and who took the exact same test. For adolescents born before 1940, boys had a moderate advantage, and this had increased by 38 percent for those born after 1958. Heights were still increasing in wealthier European nations from 1969 to 1979, and Danish and Swedish conscripts (all men) gained the most in spatial abilities and relatively less in domains that typically show no or smaller sex differences (such as verbal abilities). Cause-and-effect has not yet been determined, and so we don’t know if the diverging sex differences in height and cognition are driven by the same underlying processes, but there’s reason to believe they are, at least partially (education might also contribute to the cognitive changes).

It is not simply that sex differences in traits that typically favour one sex or the other become larger as conditions improve. Rather, the sex-specific differentiation of these traits is most likely to occur when those traits are rapidly growing or need to be expressed at maximal capacity. Men’s relative height is compromised the most if they experience nutritional and caloric deficits in the first few years of life or during the pubertal growth spurt. Similarly, girls have early advantages in language development, and these appear to be the most vulnerable to disruption during the last month of gestation through the first few years of life. Preterm girls (born at 32–33 weeks, not extremely preterm) or girls exposed to toxins in utero or during their preschool years suffer various language deficits relative to full-term or unexposed girls, whereas boys exposed to the same stressors hardly suffer at all. Boys’ advantages in many physical competencies, such as running speed and endurance, are evident in childhood and become larger during adolescence. Poor nutrition and disease disrupt these competencies more thoroughly in boys than in girls, reducing or even eliminating typical sex differences.

Conclusion

The great divergence in gender-equal societies is counterintuitive and was completely unexpected by most social scientists, particularly those biased toward a blank-slate view of human nature. Yet it makes sense in terms of wealthy egalitarian societies offering more options in life and looser social mores that enable the fuller expression of underlying sex differences in personality, proclivities, and lifestyle preferences. No doubt post hoc explanations, such as stereotypes and the stubborn persistence of the patriarchy, will still be offered in an attempt to rescue the blank-slate theory. These approaches fail to explain why a patriarchy would promote language and verbal memory in girls and women, and promote women’s movement into higher education and into high-status fields men once dominated. Surely, the opposite would happen in a real patriarchy.

Moreover, any such explanations fall flat when it comes to explaining the widening sex differences in height and weight (i.e., lean muscle mass), and the finding that these are correlated with widening sex differences in some cognitive and other domains (e.g., occupational preferences and choices). It makes sense that living conditions that improve height also improve the functioning of other physical systems, including the brain. This is a likely contributor to the Flynn effect, that is, cross-generation gains in cognitive performance in wealthy nations. But this does not explain why such effects would differ for women and men. An evolutionary perspective does. An evolved advantage comes with vulnerability and the advantaged sex (whatever the trait might be) pays a heavier price when the bottom falls out. This was illustrated above with the demonstration that poor conditions while growing up compromise men’s height and weight more than those of women. This pattern appears to hold for other traits, including those that typically favour girls and women.