New Year

A New Year’s Message from the Managing Editor

The watchwords for this year are clarity and calm.

“Men can do nothing without the make believe of a beginning,” writes George Eliot at the opening of her novel, Middlemarch: A Story of Provincial Life. Some events can be traced to precise moments of origin: a tiny dense fireball exploding to create the universe; a spermatozoon piercing the full moon of an ovum to create you. But beginnings that can be pinpointed with this level of precision tend to be remote in time and rarely occur on a human scale. And even when an event in a person’s life clearly marked the beginning of something important, the significance of that event—even the fact that it was a beginning—can only be grasped in retrospect. If you have been present at the birth of a child, you know how it feels to consciously witness the start of something momentous. But life holds few such occasions and therefore, in our need for renewal, for fresh starts and second chances, each year we stamp an arbitrary moment in time’s continual flow with symbolic meaning and say “let’s start from here.”

In the Zoroastrian tradition, on a rotating date in mid-August, we declare navroze, a new day; we garland temple archways with marigolds and white-robed priests carry fires in silver braziers to suburban Bombay apartments to smoke away the demons of the past. In Iran, they light fires too—this time, on the last Wednesday of the boreal winter—and leap over the flames. Meanwhile, on the other side of the globe, if you walk through the streets of the business district of Buenos Aires, on the final workday of December, you will be showered like a bride with tiny pieces of white paper as people in the offices above gleefully rip the pages out of office calendars that marked the outgoing year and scatter the scraps on the wind.

It’s been a year and a month since I upended my own life, turned the map on its head and moved to Sydney to work full-time here at Quillette. It’s been two years exactly since I first arrived in Australia, after swigging champagne from miniature plastic bottles twice on the flight over, as we celebrated the New Year’s midnight hour in two successive time zones. Within days, I knew that I wanted to stay here. And very quickly after that, I knew I wanted to work at this magazine. There were two qualities in particular that drew me to Quillette. They are perhaps the most important qualities a magazine of this kind can have: clarity and calm.

To attempt to view things clearly and write about them in plain language always takes some courage. The universe is not arranged for our convenience, the laws of nature don’t care about your sensibilities. When you try to investigate things dispassionately, you always run the risk of discovering something that will make you uncomfortable or sad; or will prove you wrong or make you feel like a fool. The truth will set you free—but sometimes it sets you free like an unwanted puppy whining by the roadside as its owners drive away, or like an unmedicated schizophrenic when the asylum closes and the occupants are left to urinate in carparks and beg for change on subway platforms. As FIRE president and First Amendment lawyer Greg Lukianoff neatly puts it, the most important reason to allow freedom of speech is because when we don’t force people to conceal or lie about what they are really thinking we are better able to “see the world as it really is.” But this is also one reason why so many people favour censorship—no matter how much lip service they might pay to freedom of expression, most people don’t want to hear painful truths. There will always be censors and bowdlerisers and eSafety Commissioners because of the deeply rooted human impulse to protect ourselves against hearing things that hit home.

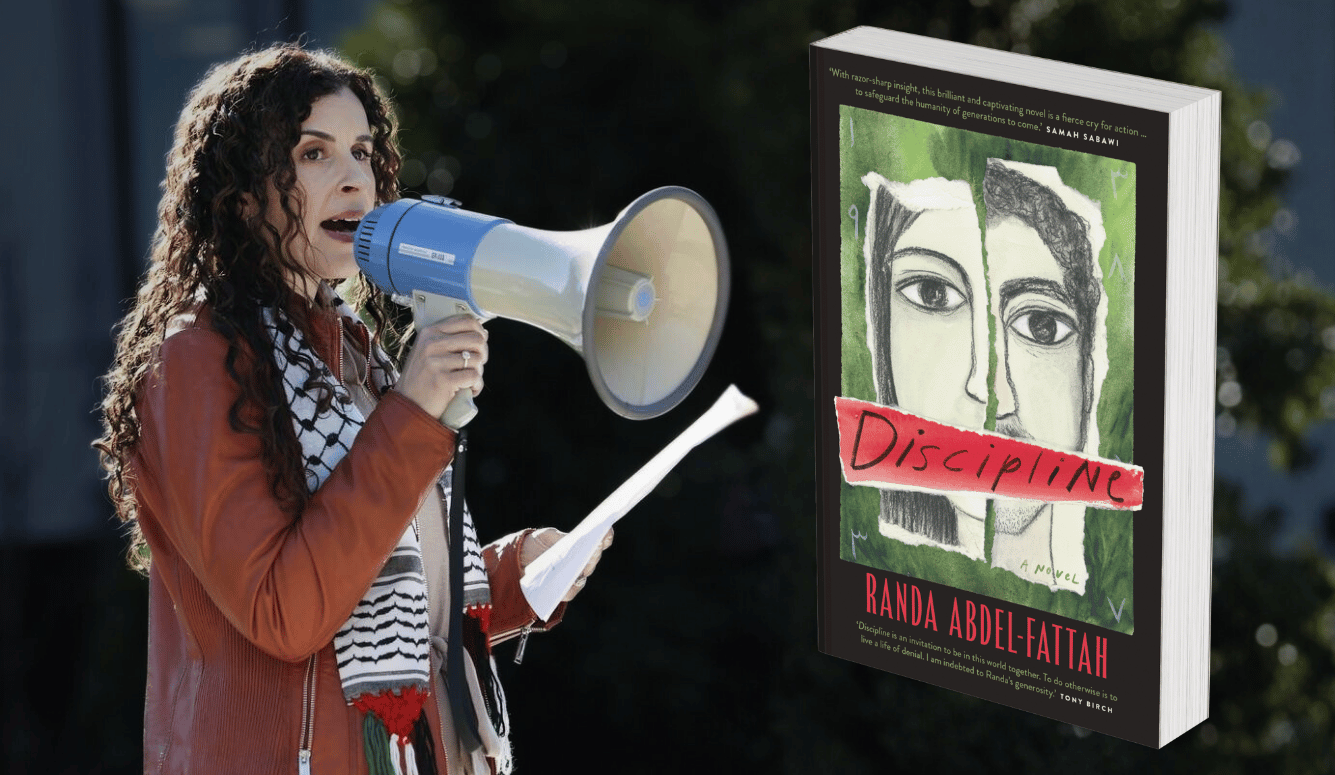

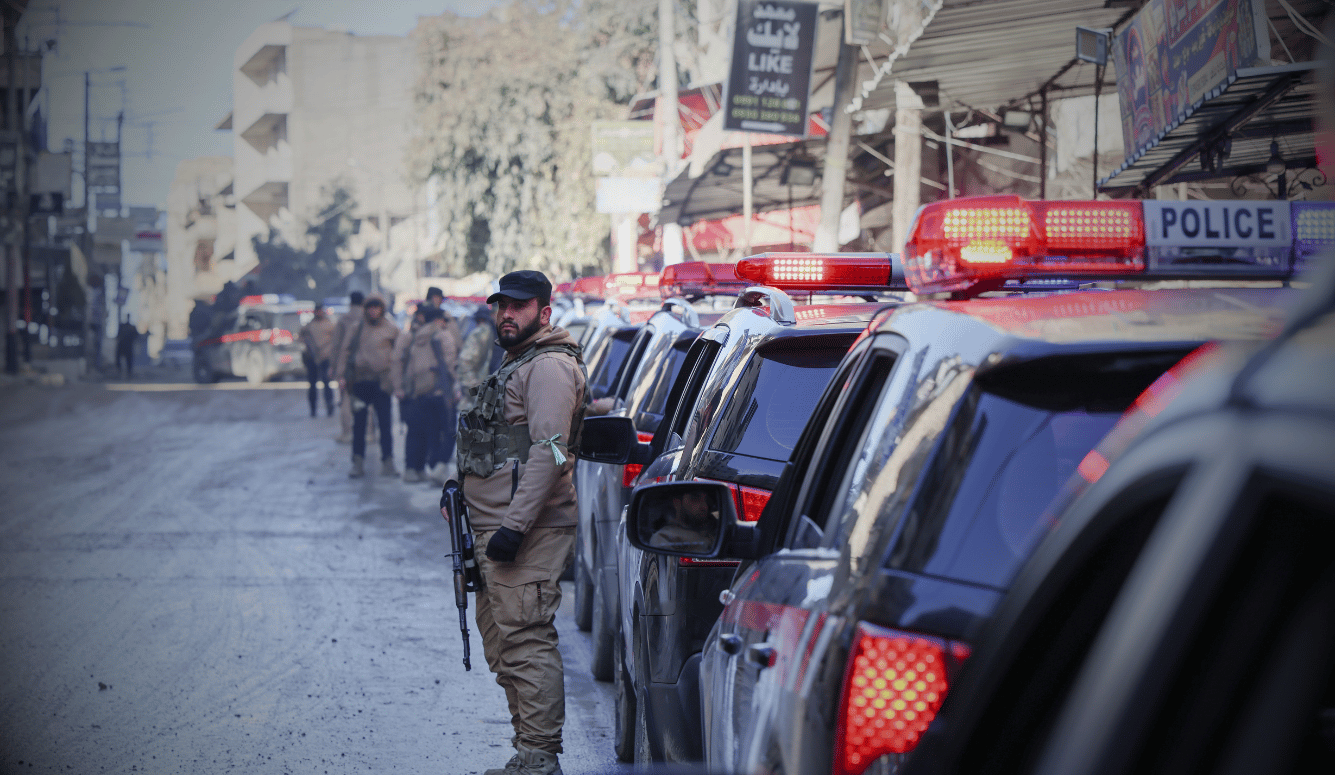

This reluctance to state things plainly and try to look at facts head-on is especially pronounced in academe. Academics have always had a tendency to use specious jargon to make their work sound more important. Universities are full of naked emperors, striding along with their hairy balls swinging in the breeze, demanding we acknowledge how chic their trousers are. The less obvious it is how a discipline can concretely contribute to society, the more its practitioners tend to take refuge in obfuscation to hide the triviality of their concerns. Unapologetic political bias and ideological capture has made these tendencies worse, especially in the arts and humanities, disciplines in which Michel Foucault and Karl Marx remain the most name-checked and cited thinkers: two people who were profoundly wrong and whose influence on posterity has been generally pernicious. And the problem is not just that the often migraine-inducing writing in those fields conceals muddled thinking—it also provides cover for deeply misguided political ideologies like communism and decolonialism, which often condone or even romanticise savagery. 7 October 2023 was a clarifying moment in that regard, encapsulated by a tweet by writer Najma Sharif Alawi: “What did y’all think decolonization meant? vibes? papers? essays?” The pro-Palestine movement has demonstrated how much influence this ideology continues to have.

Quillette is an antidote to the worst excesses of academe: a place where scholars can speak freely, including about controversial topics, without convoluted language or opaque jargon. But it is not merely a place to air political grievances. As my colleague Jonathan Kay has noted, “Quillette was created as a haven for exasperated intellectuals. But we wisely fronted the intellectualism and migrated away from the exasperation.” This brings me to the second key value: calm. That, too, has always been central to our mission. In 2020, Quillette published a book called Panics and Persecutions—a title that neatly expresses everything we oppose. Zealous partisanship of every stripe tends to whip up panic, especially on social media, where anger drives clicks. On the Left, the panics have centred on such things as police violence, climate change, and transphobia; while the Right has been more exercised by such things as illegal immigration and crime. But on both sides, too many people are spending more time reacting to things than thinking about them—even getting enraged by out-of-context video snippets that could be staged or produced by AI.

The salutary calm we offer at Quillette doesn’t stem from complacency or wilful blindness to the very real challenges facing the world at the start of 2025. Instead, it is rooted in three things. First, we offer thoughtful, long-form analyses of political issues. Reading carefully written articles encourages an interest in things for their own sake: an exploratory attitude that is the opposite of kneejerk partisanship and panicky reactivity. Second, alongside a focus on politics, we encourage an appreciation of art, history, science, literature, cinema: life-enriching disciplines that help to put transitory political concerns into a larger perspective.

And finally, most importantly, for all our critiques of the ideological capture of institutions, our exposés of injustice and confusion, all our debunkings of misguided orthodoxies and establishment pieties, at Quillette we are optimistic. We are living the longest and healthiest lives in history and are on track to overcome some of the most intractable problems humanity has ever faced. Elon Musk’s reusable rockets have made space exploration far more feasible than ever before, expanding the bounds of possibility for humanity immeasurably. Meanwhile, Ozempic and similar drugs are helping us face down our most intimate enemy, levelling the genetic playing field and liberating people from the evolved urge to gorge in preparation for a famine that we will never face. The development of GLP-1 agonists is a good example of a recurring pattern in human history. When we solve one problem—hunger—through technology (agriculture), the solution itself leads to a second problem—in this case, widespread obesity. But then, through human ingenuity, we solve that problem too. Life is a continual series of error corrections and readjustments.

When the first Homo sapiens arrived in Australia, they hunted the local megafauna to extinction and burned the dense forests of the interior to the ground, creating a desert. But now that same red-soiled outback landscape is both familiar and beloved. Later, people came here in irons, staggering onto land half-blind from months in the darkness of a ship’s hold into a strange place a world away from everything they knew. And yet once again, over the years, the exiles became natives and the place of banishment became home and is now full of iconic landmarks, scenic beaches, overpriced real estate, and the best coffee on the planet. Change is inevitable, but nostalgia often gives way in time to the deep familiarity that breeds not contempt but love.

The Germans wish each other “einen guten Rutsch” (‘a happy slide’) into the new year. We’re tumbling down that slope right now. The coming year is likely to be horrifying, tragic, and also exciting, beautiful, and at times absurd. All we can do is welcome it and hope it brings us more clarity and calm. After all, we’re lucky to be here, against all the odds. Happy New Year!