Podcast

Podcast #263: In Defence of Julia the Elder

Quillette podcast host Jonathan Kay speaks with Joan Smith, whose new book critically examines the 2,000-year-old propaganda campaign against imperial Rome’s leading women.

[00:00:00] Jonathan Kay: Welcome to the Quillette podcast. I’m your host, Jonathan Kay, a senior editor at Quillette. Quillette is where free thought lives. We are an independent, grassroots platform for heterodox ideas and fearless commentary. If you’d like to support the podcast, you can do so by going to Quillette.com and becoming a paid subscriber.

[00:00:21] This subscription will also give you access to all our articles and early access to Quillette social events. And today I’ve got kind of a two-for-one episode for you—in which I combine two of my favourite Quillette themes: the culture war over sex and gender, and books about ancient history. Now, I know what you’re thinking…

[00:00:41] Who could possibly be sufficiently interested in both of these subjects—aside from me, of course—to sustain a half-hour-plus conversation on this? The answer, as it turns out, is English journalist Joan Smith, who you may know from such popular Quillette essays as Queen of the Gender Crits and Gaslighting Scottish Rape Victims in the Name of Trans Inclusion.

[00:01:03] Well, it turns out that Joan is also an expert on ancient Roman history, and has written a new book about it, with a focus on the historical misrepresentation of women in imperial Rome’s Julio-Claudian dynasty. And, for those following at home, that’s the dynasty that comprised the first five Roman emperors: Augustus, who we’ll be talking about a good deal, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, and Nero. As Joan writes in her book, many of the women who were born or married into this dynasty met cruel fates, sometimes after being libelled as sex fiends—“slut-shaming” in modern parlance. The evidence for these claims was quite thin, but the allegations were widely believed anyway, because such women were often deemed inconvenient to the male powers-that-be, whose main preoccupation was always politics.

[00:01:52] And so even women as prominent as Julia the Elder—that’s Augustus’s only child—were sent to their doom once their existence threatened some dynastic scheme cooked up by the emperor or some other powerful figure. Enjoy my conversation with Joan Smith, author of the new book, Unfortunately, She Was a Nymphomaniac, A New History of Rome’s Imperial Women—which we recently excerpted on the Quillette web site.

[00:02:15] So Joan, like a lot of my listeners, I know you primarily from your essays about sex and gender in the modern age. And yet, I read the introduction to this book, and it turns out you’ve been living a double life. Not only are you an essayist about ripped-from-the-headlines issues, but you also are apparently a fluent Latin speaker and have spent much of your life delving into primary sources regarding the history of Julio-Claudian women.

[00:02:44] This was a huge revelation to me. How have you managed to develop this double intellectual life?

[00:02:50] Joan Smith: Well, I was incredibly lucky because I come from a very working-class family, but I went to state schools, grammar schools, two grammar schools where they taught Latin and I took to it. It was extraordinary. It was like it opened up an entirely new world for me.

[00:03:04] And I just threw myself into it. I loved it. I decided to go to university and I was going to read classics. In the end, I read Latin because I love Latin much more than Greek and I know it much better. And it also had a huge influence on my career, because reading the Roman historian Tacitus at an early age actually formed my view of how to write and and how to use rhetoric.

[00:03:31] I absolutely loved Tacitus. He has such an economical style and he’s so argumentative and so confident and terse—and I think that influenced all the writing that I’ve ever done. So it was always there in my background. I must’ve read Latin every day from the ages of 12 to 21.

[00:03:53] I was torn… I wanted to be a writer. I knew I either wanted to be a journalist or I wanted to do a PhD and I applied for both. I got a grant to do a PhD from my old university on this very period of the early Roman Empire and I [also] got offered a job in journalism; and I took a deep breath and thought, I’m going to become a journalist.

[00:04:16] I want to be a writer and I think I can go back to this [historical subject] at some point. And now many years later, I’ve gone back to it.

[00:04:22] Jonathan Kay: Among the other great qualities of your book is a fantastic title, which comes with a fantastic backstory. The title is, Unfortunately, She Was a Nymphomaniac. I want you to tell the story of how you picked that…

[00:04:35] It’s from an anecdote in Italy. By the way, I’m guessing you’re also a fluent speaker of modern Italian, right?

[00:04:41] Joan Smith: No, no… I can just about get by, but that’s all. But I’ve been going up and down to Italy while I spent two and a half years writing this book and doing the translations and so on.

[00:04:51] And about 18 months ago, I was in Rome and I went to the Palazzo Massimo, which is the huge Renaissance palace next to the rather awful central railway station, Termini. And upstairs there is a room where they have frescoes from the Empress Livia’s country villa, which is about 15 kilometres north of Rome, and they were brought there to preserve them because they were found in almost pristine condition.

[00:05:16] So I was marvelling at these frescoes when a guide came in, an Italian guide, but anglophone, so he had a group of English tourists, and he started summarising the history of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. You know, Augustus was the first emperor, he said, and his second wife was Livia, and they were married for more than 50 years, and they loved each other very much… at which point my hackles rose because I’m not convinced by that. And he said they didn’t have children together—the only child Augustus had was with his first wife, and “unfortunately, she was an a nymphomaniac.” And this is so garbled and so nonsensical, as well as being incredibly misogynist.

[00:05:55] So I just say, “Excuse me, the first thing is that Julia’s mother was not Augustus’s first wife. She was his second wife, Scribonia. You’ve forgotten Augustus’s first wife, Claudia Pulchra, who’s actually incredibly important because she’s the stepdaughter of Mark Antony.” And I said, “Also, Julia wasn’t a nymphomaniac.”

[00:06:12] And he looked at me and he said, “It’s all in the sources, signora.” So I said, “Yes, I am familiar with the sources.” And I said, “I take it you’re referring to Seneca’s famous essay, De Beneficis—On Benefits—in which he says that although Julia was the most recognisable woman in the Roman Empire after her stepmother Livia, and lived in a palace on the Palatine Hill, she was so insatiable for sex that she went down into the Forum every night and sold her body to every passing barman and gladiator.”

[00:06:42] And he said, “Yes.” And I said, “Do you really think women behave like that?” And, I said: “Tell me this. So Julia was famously fertile. So she has five children with her second husband, Agrippa. She has a child who dies with her third husband, Tiberius. And shortly after that, they separate. And this is when she’s supposed to have gone down into the Forum and started this second career as a prostitute.

[00:07:04] And actually she was only about 30 at the time. She was very fertile. She never got pregnant again. How did she do that?” He looked at me and he said, “Well, maybe the sources exaggerated.” And I said, “Well, maybe they did. And maybe they were actually informed by ancient misogyny, which believed the worst of all the Julio-Claudian women.”

[00:07:21] So in the end, I suddenly realised the entire room had come to a standstill.

[00:07:25] Jonathan Kay: So there are some two dozen Julio-Claudian women discussed in the book, but for me, the central case study here is Julia, the only daughter and the only child of Rome’s first emperor, Augustus. Can you give us the backstory of Augustus’s rise to power, which I think helps explain some of the political context in which he imposed such cruelties on his only child.

[00:07:52] Joan Smith: So basically what happens is there are terrible civil wars. Augustus Octavian, as he then is, is the outright winner, defeats Mark Antony, Cleopatra, and sets up basically a system of one-man rule instead of a republic.

[00:08:05] And the women become incredibly important because this is going to be a hereditary regime, whereas previously, two [consuls] were elected every year. But the first five emperors, from Augustus to Nero, are incredibly bad at having sons. And so that makes the daughters very important.

[00:08:23] And Julia is one of the central characters in my book because she is Augustus’s only child. And when his plans to have children with his third wife, Livia, come to nothing—they’d have a child who’s premature and dies—she suddenly becomes the focus of the regime. And she is a pawn in her father’s plans.

[00:08:42] And quite a bit of the early chapters in the book is about the way that her father handed her from man to man. First of all, to her cousin, Marcellus; he dies. He then hands her over to his best friend, Agrippa, who is a general—basically the man who plotted [Augustus’s] victory at the Battle of Actium.

[00:09:01] These people are very, very interrelated. It’s very incestuous. So he marries her to her stepbrother Tiberius, which is a fantastically unhappy marriage. Eventually, Tiberius goes to live in Rhodes to get away from the marriage, leaving Julia on her own in Rome, and she’s eventually exiled by her father—supposedly for debauchery, though it’s probably for political reasons.

[00:09:29] And her life is terrible. She’s at the age of about 35. She’s sent to live on a very distant island off the west coast of Italy. I went there a couple of years ago, and it’s basically about 800 metres by 3,000 metres. It’s absolutely tiny, miles from shore, and woman after woman in this dynasty was rowed out there, quite often in chains.

[00:09:51] Jonathan Kay: But despite the fact this is obviously an extremely important historic site, when you went to the island, you actually had trouble finding it, right? Like, you were kind of wandering around asking locals…

[00:10:03] Joan Smith: The third person I asked was a woman hanging out her washing, and she was the person who told me how to get there.

[00:10:09] I mean, it’s not open to the public. There’s a vast Augustan villa. Augustus had a villa built there. He never visited himself, but he used it as a prison for inconvenient relatives. And the subsequent emperors did the same. So five of the women in the book were exiled there, and four of them were either murdered or committed suicide because the conditions were so appalling.

[00:10:30] Jonathan Kay: So in the standard progressive discourse about misogyny, a lot of the problems are traced to Judeo-Christian civilisation or whatnot, but [what we are talking about] is several hundred years before Rome became a Christian society. What was the ideological basis for this misogynistic treatment of even the wealthiest and most powerful women in society? All their privilege, to use a modern term, didn’t insulate them from this deadly misogyny. In fact, it just made them a greater target.

[00:11:00] Joan Smith: I think it’s all rooted in the importance of knowing who your children are. And in the Roman republic, women were venerated as long as they stayed within very narrow confines.

[00:11:12] So, a woman would die, she would have a lovely tombstone, it would say what a good seamstress she was and how she made all the household’s clothes and she had children and so on. They existed within very narrow parameters. When Augustus creates the Principate, the Empire, under the pretence of restoring the public, one of the ways he sets up the apparatus for his family to remain in power is by creating a cult around his immediate relatives.

[00:11:41] And this means that women emerge from the domestic sphere for the first time in ancient Rome, and suddenly they appear on monuments, there are statues of them; and there [had been] virtually no statues of women. not real life women, during the Roman republic. There are statues of goddesses like Venus or water nymphs or women like that, but real women don’t have that position in public.

[00:12:02] And the establishment of the Principate actually brings them…Augustus brings them deliberately into the public sphere. They’re recognisable, they’re wealthy, some of them are beautiful, they’re admired. But at the same time, they’re still existing within those same parameters.

[00:12:22] And in fact, Augustus actually tightens the laws affecting women. So, for a man to sleep with a prostitute is not adultery. But a woman sleeping with anybody else is adultery. And in fact, one of Augustus’s laws was to say that a father who discovers his daughter sleeping with another man is entitled to kill her.

[00:12:40] I mean this was a very vicious regime if you’re a woman And what the book is about really is how women try to negotiate their way through that… first of all by seeing how they could push the boundaries, then discovering that terrible things would happen to them, and eventually you get to Julia’s granddaughter Agrippina the younger who manages to become an empress herself. Yet even so, she’s still murdered on the orders of her son.

[00:13:06] But of course there are statues of the women. There’s some very beautiful Roman cameos showing some of the women. There’s one of Livilla, one of the women in my book, who had twins. There’s a very beautiful cameo of her, with her little tiny twin sons at the bottom.

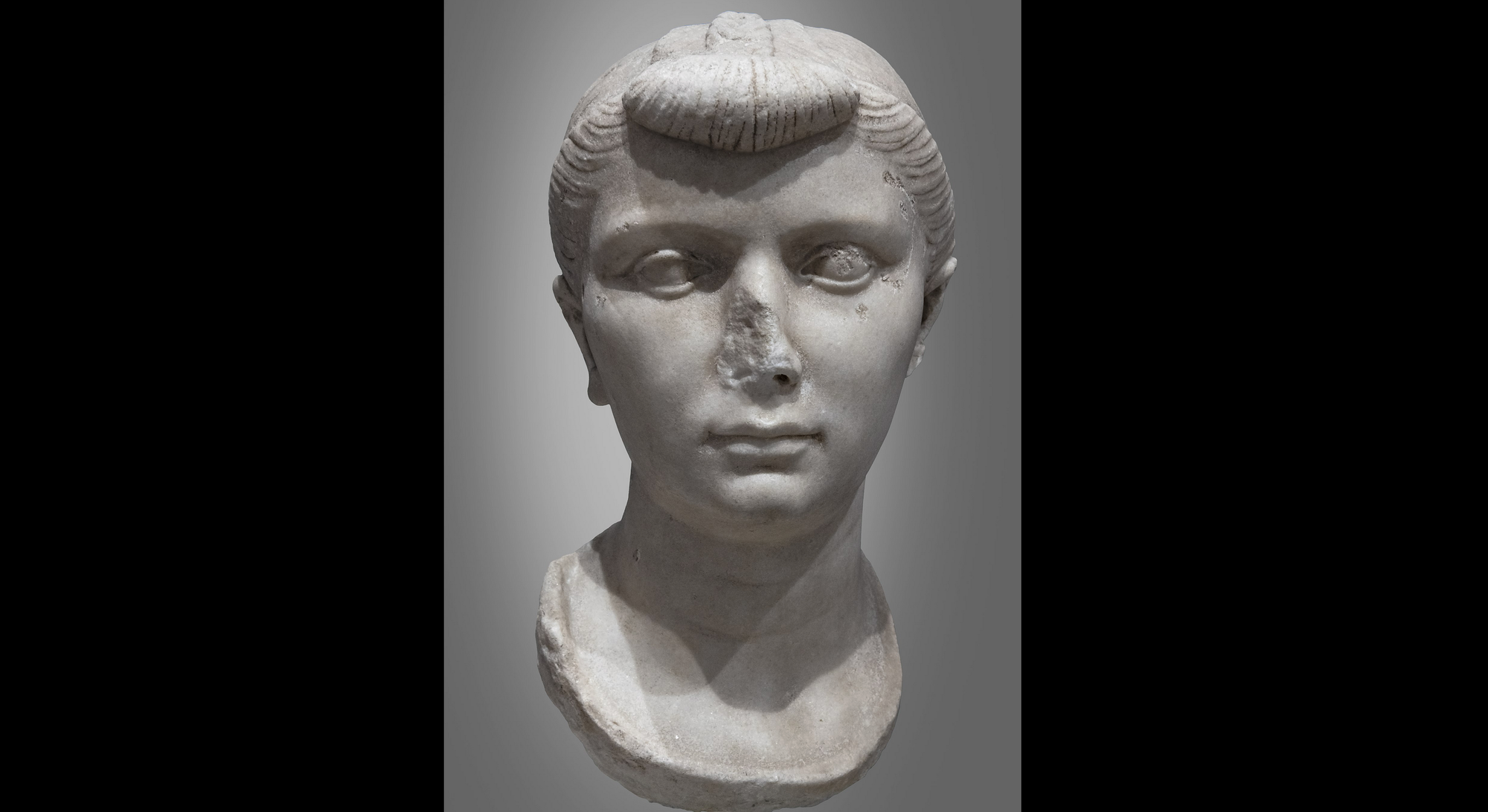

[00:13:25] However, when those women transgressed—she was starved to death by her own mother. And they would declare what’s called a damnatio memoriae—which is a late term, a Renaissance term, but basically an official decree by the Senate that this person didn’t exist. And so we have I think only one reliably identified image of Julia, a head, a marble head.

[00:13:49] [With] Livilla, virtually every image of her was destroyed. Messalina [the third wife of Roman emperor Claudius] the same. And it was sheer chance that one or two of these statues survived. They were quite often starved to death. And there’s a parallel between that and what happens to the iconography.

[00:14:08] So the women are starved to death, which is a very hard, horrible, painful and lengthy way of killing somebody. It’s the literal destruction of the body. And then the statues are destroyed as well.

[00:14:18] Jonathan Kay: This obsession with erasing history through destroying statues and whatnot strikes me as an ancient foreshadowing of the modern totalitarian impulse to rewrite history, throwing things down the “memory hole,” to quote George Orwell.

[00:14:31] In terms of the manner of execution, though, or de facto execution, was there a stigma against executing women in a forthright way, like beheading them, in the same way you would execute a male political opponent accused of treason or whatnot? Was starvation a way of killing them without being seen as physically slaughtering a woman?

[00:14:54] Joan Smith: A woman couldn’t be executed if she was still a virgin. And so there are instances of women being raped, girls, teenage girls or younger being raped before they were executed. The starving to death, I think it comes, from the cult of the Vestal Virgins… there’s a temple in the centre of Rome which was the headquarters of the cult of the Vestal Virgins and there would be a chief Vestal and then several priestesses below her and they were venerated but they had to be perpetual virgins. And if a Vestal Virgin was discovered to have had sex with somebody and no longer a virgin, she would be walled up and starved to death somewhere in the palace.

[00:15:30] And I think that’s where the idea of starving women to death comes from.

[00:15:34] Jonathan Kay: One of the motifs you see in pagan mythology is that women are venerated either as virgins or as sex machines. Sometimes pagan shrines had sacred prostitutes whose sexual activities were actually incorporated into the spiritual life of these pagan communities.

[00:15:54] I’m wondering why women just can’t have ordinary sex lives [according to these systems of belief]. They’re either pure as the driven snow and never have sex, or they’re prostitutes or sacred sex workers of some kind whose only function in life is just to have sex with men.

[00:16:10] Joan Smith: Well, I think it’s all about control. And in Rome, prostitutes, there’s a number of Latin words that refer to prostitutes, but most of them had a fairly hellish time.

[00:16:20] Most prostitutes in Italy of this period would have been slaves or ex slaves. They would have had very little choice of what they were doing. They wouldn’t have received much of the money they were supposed to have earned. Tourists go to Pompeii and they’re very keen to see the Lupanare, which is the brothel.

[00:16:39] And there are frescoes, but people don’t actually always appreciate, tourists don’t always appreciate what terrible lives those women had. You’re very near the coast there, so it’s a port. There’s a huge influx all the time and an exodus of foreign sailors who come ashore, they have some money, they want to get drunk, they want to have sex.

[00:17:02] It was a pretty brutal existence. But at all levels, there is control of women’s sexuality. Women don’t get to decide. You didn’t have much choice. If you decided that you were going to be a Vestal Virgin, that wasn’t a career choice. And if you ended up in a brothel, that wasn’t a career choice either.

[00:17:20] In the book, you see how the sexuality of women was being… and the bodies of women were being controlled all the way through this period, which is basically about a century. It’s from about 27 BC to 68 AD. In that period, the age of marriage for girls was twelve, and there’s a recurring theme in my book of very young girls, probably before they’ve even started their periods, being married to much older men.

[00:17:45] And when the older men die, then their father would marry them off to somebody else, which is what happened to Julia. And the girls, the women had no say in that. And it’s also why there is very high perinatal mortality in ancient Rome, because girls are getting pregnant at fourteen and fifteen, when their bodies aren’t fully enough developed and they die in childbirth.

[00:18:10] Jonathan Kay: Thanks for listening to this preview of our latest podcast. We hope you’ve enjoyed the discussion so far, but we’re just getting started. To hear the full podcast episode and gain access to our entire podcast library, we invite you to become a Quillette subscriber. We offer three subscription tiers to suit your needs.

First, podcast only. For just five [US] dollars per month, you’ll get access to our full podcast library, including the rest of this episode. This is our most affordable option for podcast enthusiasts. Second, full access. At 10 [US] dollars per month, you’ll get everything in the podcast-only tier, plus unlimited access to all articles on Quillette.

Third, there’s VIP. For 25 [US] dollars per month, enjoy all the benefits of full access, along with free tickets to our Quillette social events. If you’re primarily interested in our podcasts, the podcast-only tier at five dollars per month is perfect for you. Either way, if you’re ready to join us, it’s quick and easy. Simply visit our website at Quillette.com and then click Subscribe. From there, you can choose the subscription tier that best fits your interests. We look forward to having you as part of our community.