Ancient History

‘Shameless Beyond the Curse of Shamelessness’

In a new book, Joan Smith critically examines the historical mistreatment of Ancient Rome’s leading women—including Emperor Augustus’ daughter Julia, who was denounced as a nymphomaniac and cast into exile.

The Pontine islands lie in the Tyrrhenian Sea, off the west coast of Italy, halfway between Rome and Naples. There are six islands in the archipelago and one of them, Ventotene, is the summit of an extinct volcano. It’s 53 kilometres from the mainland and the journey from Rome by modern transport takes about five hours, starting with a train to the port of Formia on the Gulf of Gaeta.

It’s advisable to go in the summer when the fast ferry takes about ninety minutes, heading into open sea and rapidly losing sight of Formia; even today, nothing but water is visible for more than an hour until the low-lying island of Ventotene comes into vision.

The ferry anchors in a modern harbour built on the far side of the little Roman port, disgorging tourists and local people who’ve returned with essential supplies; the island is small, 3,000 metres by 800 metres, and not much grows here apart from lentils.

Around 750 people live permanently on Ventotene, catering to the tourists who stay in spa hotels or hire diving equipment to explore the azure waters that surround it. Picturesque houses in pastel colours straggle up the hillside, but it’s an unsettling location for anyone who knows that Ventotene functioned as a prison—and a place of execution—for some of the most famous women in Roman history.

In the late first century BC, the Roman emperor Augustus built a palace on the northern tip of the island, which was then called Pandateria, but there’s no evidence that he ever visited it. The extensive archaeological site where it stood is closed to visitors and barely signposted; when I visited Ventotene, my question about how to get there was repeatedly met with shrugs.

After walking out of town, I was finally directed to the site by a woman who was hanging out her washing. She pointed up some rickety steps next to a hand-painted sign to what’s known locally as the Villa Giulia, and I found myself peering over a fence at the ruins of the farm that once supplied the inhabitants of the palace with food.

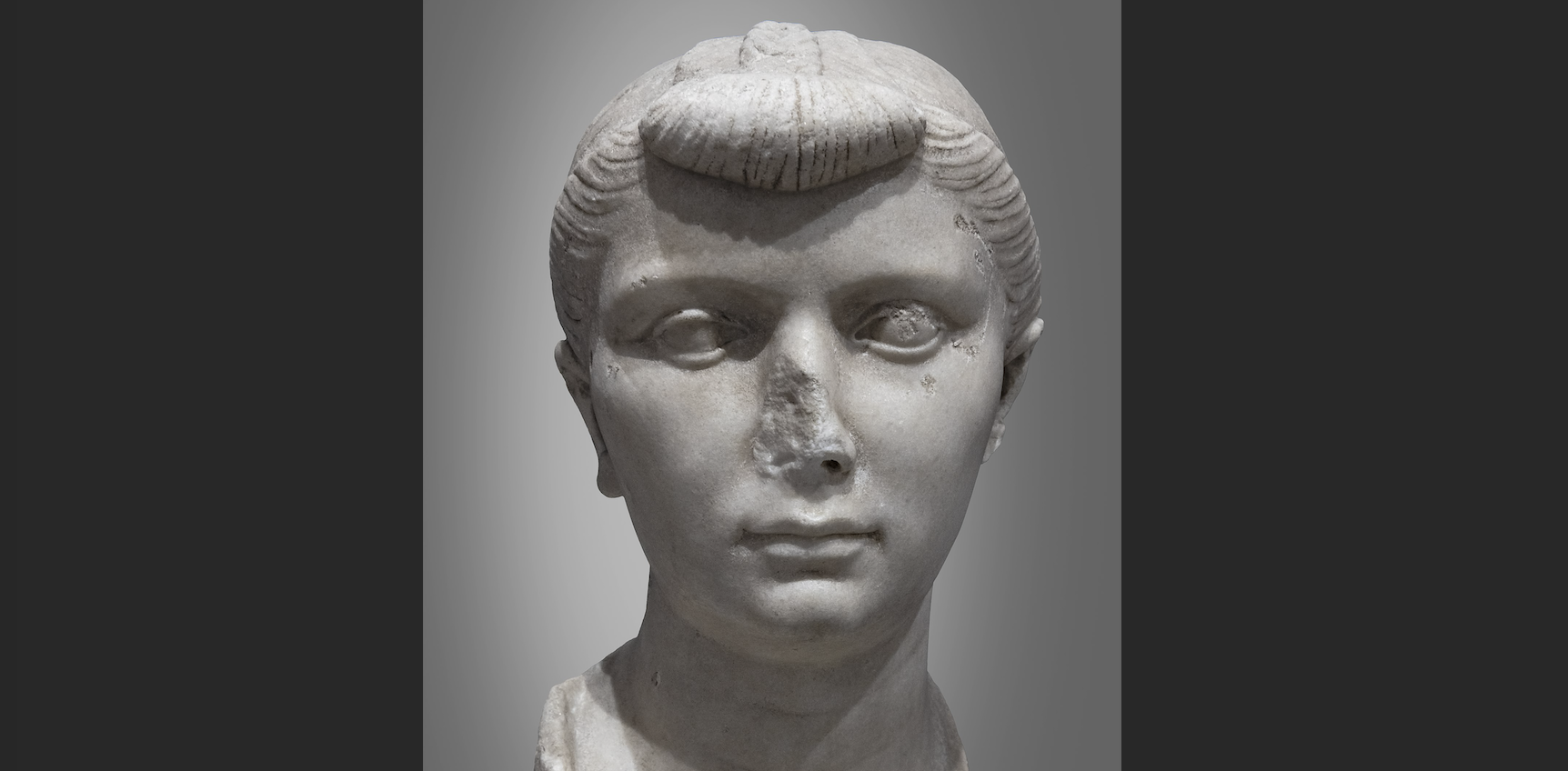

Its most famous resident was Augustus’s daughter Julia, who was imprisoned in the palace for five years after she was disgraced and exiled in 2 BC. Julia was eventually moved to the mainland, but three more women from Rome’s Julio-Claudian imperial dynasty would be imprisoned here—and, unlike Julia, they would all die here.

Lovely as the island appears today, its history is overshadowed by the fate of these women, who were forced to undertake the long journey from Rome in closed litters, listening to the clanking swords of the soldiers preventing their escape; we know that at least one of them, Julia’s daughter Agrippina, was brought here in chains.

They would have been tormented by fear and despair as they were rowed across to the rocky island, the many hours in a boat a warning of how far from the mainland their prison would turn out to be. It was still being used as a dumping ground for inconvenient women in 95 AD when the emperor Domitian exiled his niece Flavia Domitilla to Pandateria, allegedly for converting to Judaism.

Julia was thirty-six or thirty-seven when she was exiled to Pandateria. She had five children from her former marriage to Agrippa (who’d served as Augustus’ principal military lieutenant): two daughters, Julia and Agrippina, as well as three boys. They were aged between ten and eighteen, and she would never see any of them again.

The scale of her disgrace is hard to imagine: she had been accused of adultery and plotting against the regime, denounced in a letter by her own father, which was read aloud to the Senate. Her estranged husband Tiberius had been ordered to divorce her, and four of her alleged lovers were exiled to other parts of the empire; a fifth, she would later learn, had either been executed or forced to kill himself.

Accusations of immorality were often a distraction from alleged political offences that were an embarrassment to the regime, especially if they involved close relatives of the emperor—and few were closer than his own daughter.

Augustus was astonished by the popular reaction in Rome, where angry crowds gathered to protest against Julia’s banishment, but he refused to change his mind; some ancient sources even suggest that he seriously considered having her executed. Instead, he decided to make sure her conditions of imprisonment were as harsh as possible, banning her from drinking wine and eating anything but the plainest food (a prohibition that hardly seems necessary, given the island’s limited resources).

Julia’s sole consolation was the presence of her mother Scribonia, who voluntarily accompanied her into exile. She was approaching seventy by now, and it was no small matter to give up her existence in Rome—where her adult son from an earlier marriage may still have been alive and she had at least six grandchildren—to share Julia’s disgrace on the windswept island. But Scribonia had already lost her elder daughter, Cornelia, whose death in 18 BC was recorded by the poet Propertius. (He wrote an elegy addressed to Cornelia’s widower, Paullus Aemilius Lepidus, in which the dead woman tries to console her grieving mother.) Sixteen years later, Scribonia didn’t want to lose another daughter. But even so, her decision to accompany Julia into exile was a leap into the unknown.

Nothing like Julia’s exile had happened before in Rome, and the two women may have heard reports of the demonstrations from gossip passed on by sailors on the ships that brought supplies, raising their hopes of a reprieve. If anything, however, the protests backfired: Augustus was furious, calling on the gods to curse the defiant crowds with similarly disobedient wives and daughters. The protesters were not cowed; when Augustus declared that fire would mix with water before he would recall Julia to Rome, they mocked him by tossing burning torches into the Tiber.

The summer of 2 BC was a significant milestone for the emperor. It had been twenty-five years since he’d accepted the title of Augustus. And earlier that year, he had been awarded another, Pater Patriae (Father of the Nation), by the Senate. He stuck to the conceit that he had restored the Roman republic, but no one doubted that he was in charge, or that a member of his family would succeed him as sole ruler of Rome.

He was sixty-one that summer, Livia (his third wife) around fifty-six, and he celebrated the anniversary with grand building projects, finally finishing the Forum of Augustus. The scandal that erupted over his daughter could not have been more unwelcome, but it had been brewing for a long time—and he had only himself to blame.

No daughter could have behaved more impeccably than Julia in terms of the succession, marrying men chosen by her father and producing the male heirs that Augustus had not been able to provide himself. But her marriage to Livia’s son Tiberius had broken down years earlier, and she found herself uncomfortably exposed. Tiberius left Rome altogether in 6 BC, moving to the island of Rhodes and leaving Julia in a species of limbo.

It’s important to bear in mind at this point that the daughter of the first emperor was the nearest thing in the ancient world to a celebrity, attracting attention and gossip on a scale no Roman woman had ever experienced (Cleopatra is probably the nearest comparison). Technically, she was still married, but any pretence that the marriage was intact was destroyed when her husband decamped to Greece.

The daughter of Rome’s first emperor was the nearest thing in the ancient world to a celebrity—attracting gossip on a scale no Roman woman had experienced

Julia’s situation after 6 BC was not unlike that of Princess Diana after she separated from the Prince of Wales, subject to endless speculation and the age-old assumption that an attractive single woman must be having sex with somebody. Julia tried to resolve the situation by asking for a divorce, denouncing Tiberius’s behaviour in an angry letter to her father, but Augustus would not hear of it. If Julia were allowed to divorce Tiberius, she wouldn’t want to remain on her own for long, and any future husband would become stepfather to Julia’s boys—whom Augustus had adopted—giving him a status the emperor would find intolerably threatening. Julia thus found herself in an impossible situation: still of marriageable age but neither a wife nor a widow, and denied the opportunity to find a more amenable husband.

It’s likely that she was denied the company of her elder sons, Gaius and Lucius, while her daughter Julia the Younger was married around this time and would have been living in her husband’s household. Julia the Elder relied on a coterie of high-spirited male friends from well-connected families to avoid being lonely, becoming a magnet for gossip. Whether these men were just friends, or lovers and would-be conspirators against the regime, is hard to establish, but it’s obvious that the situation was open to being misconstrued; in the years after her divorce, Princess Diana only had to be seen with a man for rumours of an affair to start flying, whether or not they were justified. But Julia’s position in the dynasty meant that her behaviour was, or appeared to be, a threat to the established social order.

The pursuit of extramarital sex by Roman men was tolerated, even expected, but it was a very different matter when the rumours related to the emperor’s daughter. The situation gained added piquancy from the fact that everyone knew about Augustus’s disapproval of adultery—his own excepted, of course. The emperor’s liaisons were mostly short-lived, with no constitutional implications, but he would have regarded a serious, long-term relationship involving his daughter as a dangerous development. Opposition to his principate was muted but widespread, particularly among patrician families, and Julia’s lover or lovers might easily become the foundation of a party of dissent. Whether or not she was aware of the political implications of an affair, this is a more likely explanation for her treatment than lurid claims about her supposed promiscuity—and might account for her father’s implacable rage towards her.

Roman historians are pretty much unanimous in condemning Julia’s conduct. The template they established has been followed to a large extent by modern scholars, who, as Julia’s biographer Elaine Fantham has observed, “have found it far easier to believe in her loose living than even the debauchery of Augustus’ other propaganda victim, Mark Antony.” To be fair, some modern commentators give the impression that they’re uncomfortable with the wilder allegations, but that doesn’t stop them reverting pretty rapidly to the nymphomaniac stereotype.

English classicist Mary Beard speculates that Julia’s arranged (forced, to be more accurate) marriages “had something to do with her notoriously rebellious sex life.” Augustus’s biographer, British historian Adrian Goldsworthy, casts doubt on the most lurid stories, but blames the emperor for failing to prevent his daughter’s behaviour “from getting as bad as it did.” Popular historian Tom Holland acknowledges that the rumours were “fetid and unsourced” but repeats them, claiming that Julia was “as wilful as she was bold.” Anthony Blond goes completely overboard and describes Julia as “arrogant, stubborn, insolent, defiant, libidinous and deeply tricky.” Even Romans for Dummies author Guy de la Bédoyère, who is generally more sympathetic than most modern commentators to the situation of women in ancient Rome, describes Julia as “turning out to be the worst daughter Augustus could possibly have had.” Rebellious, wilful, defiant: these are all adjectives that infantilise women, reducing them to naughty children or sulky teenagers.

They are harsh judgements on a woman whose principal offence, if we leave aside political considerations for a moment, was to try to take control of her own body. But it’s also worth remembering, as the empress Agrippina’s biographer Anthony A. Barrett has pointed out, that “the borderline between immorality and conspiracy is a fine one” in terms of accusations against the Julio-Claudian women. When women were regarded as their father’s or husband’s property, the act of having sex with another man was a challenge to the social order. It’s one of the reasons why it’s so hard to disentangle accusations of sexual impropriety and treason in Julia’s case, with the latter lurking in the background of sensational stories about orgies in the Forum.

It’s hard to disentangle accusations of sexual impropriety and treason in Julia’s case—with the latter lurking in the background of sensational stories about orgies in the Forum.

Rumours about Julia’s infidelity had begun to circulate as far back as her marriage to her second husband, Agrippa, which took place in 21 BC. Tacitus claims she had already started an affair with a senator named Sempronius Gracchus, whom he describes as a man notable for his intelligence and vicious wit.

There was gossip about other affairs as well, but what isn’t in doubt is Julia’s fertility, which should have been a matter of congratulation in a society where women’s primary function was bearing children. Sex and maternity are uncomfortable companions in patriarchal cultures, however, and there’s no doubt that Julia’s supposedly uninhibited sex life sat uneasily with her essential role in the continuation of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, not least because of husbands’ perpetual fear of another man’s child being covertly introduced into the family. Observers of her behaviour couldn’t understand how Julia had avoided becoming pregnant by one of her lovers, if the rumours were true, and it prompted one of the most famous ripostes from antiquity.

According to the fifth-century philosopher Macrobius, Julia was once asked to explain how her sons resembled Agrippa when she was sleeping with other men. “I never allow a passenger on board until the hold is full,” she is supposed to have replied (numquam enim nisi navi plena tollo vectorem). It’s quoted as an example of Julia’s ready wit, but Macrobius was writing 400 years later. He got the story from a first-century collection of sayings by famous people, now lost, and his own book appeared at a time when Julia’s reputation as an adulteress had long been established. The possibility that it was an ex post facto invention to account for the annoying absence of any actual evidence for her affairs has to be considered. All we can say for certain is that Agrippa never questioned his children’s paternity, but dinner-party gossip from those years set the scene for much more malicious slanders after his death.

What I am describing here is not a version of events even considered in the ancient texts. There are several accounts of Julia’s alleged transgressions, varying in tone from disgusted to pornographic. What’s striking is how short they are on detail, while siding with Augustus against the largely unspecified things his daughter is supposed to have done. The scandal that ruined her life is portrayed as a tragedy for the emperor, with scant sympathy for the half-dozen prominent people (more, if you count their families and friends) who lost everything as a result.

The historian Velleius Paterculus (19 BC–31 AD) sets the tone, describing Julia’s disgrace as a storm (tempestas) in the emperor’s household that he finds almost too horrible to describe or remember (foeda dictu memoriaque horrenda). The Latin is so bristling with disgust that it’s not easy to translate, but this is more or less what it says:

His daughter Julia, with no thought for her great father and her husband, did not refrain from any disgusting deed tainted with extravagance or lust that a woman could be guilty of, whether screwing or being screwed, and measured the extent of her status by the liberty she had to sin, justifying whatever she wanted to do by the fact that she got away with it.

Yes, but what did she actually do? Once he’s got this tirade off his chest, Velleius names five men who supposedly debauched (violassent) Julia, necessitating her removal from the sight of her country and her parents (patriaque et parentum). The assertion is not even accurate because Julia’s mother Scribonia volunteered to go into exile with her, as Velleius himself admits. But his account is the first to list her alleged lovers, recycling the old story about Sempronius Gracchus and adding the names Iullus Antonius, Quinctius Crispinus, Appius Claudius, and Cornelius Scipio. (Iullus proved to be the key figure, but they were all scions of great republican families and could easily have been seen as a threat by Augustus.)

Cassius Dio (165–235 AD) is more specific, claiming that Julia “was so dissolute in her conduct as actually to take part in revels and drinking bouts at night in the Forum and even upon the rostra,” the platform from which some of Rome’s most celebrated orators had made speeches. There is an implication here that Julia was sticking two fingers up at her father, because the rostra was where Augustus had announced some of his laws, including his legislation imposing severe penalties for adultery.

Suetonius (b. 69 AD) is another source who takes the side of the emperor, claiming that the scandal affected him so profoundly that he couldn’t bear to receive visitors for a long time afterwards. But his account, like that of Velleius, is notably short on detail. He bundles together Julia and her daughter of the same name, declaring that Augustus found them both “polluted by every type of vice” (omnibus probris contaminatas), without saying what they were. Augustus even expressed a wish that his daughter would kill herself like one of her friends, a freed slave called Phoebe who hanged herself after Julia’s disgrace.

The anecdote is supposed to show that even Julia’s closest associates were horrified by her behaviour, but it could equally have been the case, as Fantham points out, that Phoebe was terrified of being tortured; the anecdote implies that other members of Julia’s household had been interrogated, raising the possibility that some of the “evidence” against her was obtained under torture.

It’s striking that Tacitus (56–120 AD) is a lone voice of dissent, describing Julia’s offence as no more than “shamelessness” (impudicitia), and suggesting that Augustus overreacted to cases of adultery by imposing excessively harsh penalties.

So far, the allegations are all pretty similar, amounting to not much more than affairs with prominent men and outdoor parties (not so unusual on hot summer nights in Rome). But Seneca’s account is different, amounting to a Roman version of a tabloid headline: Emperor Stunned after Daughter Sells Body in Midnight Sex Orgies. He claims to be quoting from the letter of denunciation written by Augustus himself and read on his behalf to the Senate:

The divine Augustus exiled his daughter, who was shameless beyond the curse of shamelessness, and placed the scandals of the imperial family in the public domain: he said she had committed adultery with scores of men; that she had roamed the city at night in search of thrills; that she had enjoyed using the forum itself for her debauchery, and the speaker’s platform where her father had announced his law against adultery; that she went daily to the statue of [the sartyr] Marsyas where, exchanging adultery for prostitution, she claimed the right to indulge herself with complete strangers.

Seneca’s account reads like a fantasy, enjoying the contrast between Julia’s exalted status and her lewd behaviour, and expressing the idea that a “whore” exists inside every woman. We don’t know whether it’s a faithful summary of what was in Augustus’s letter or an embroidered version of it, adding details that existed only in Seneca’s fevered imagination; but it’s worth remembering at this point that conservative Roman men made no distinction between a woman who had sex outside marriage and a prostitute.

If the source was Augustus’s letter, it seems unlikely that the emperor was describing something he’d seen for himself, unless Julia was not the only member of the imperial family who had taken to wandering through the forum—effectively Rome’s red-light district—at night. So who is supposed to have witnessed and reported this behaviour? Someone who wanted to cause trouble for Julia, evidently, and tailored the accusations to cause maximum outrage, setting her supposed misconduct in a location that amounted to a deliberate insult to her father’s beliefs about women.

But why would a wealthy Roman woman, who lived in a comfortable house and had supposedly chosen some of the most personable men in Rome as her lovers, suddenly take the risk of having sex with complete strangers in one of the most exposed areas of the city? Leaving aside the likely reaction of her father, the risks attendant on engaging in prostitution in ancient Rome—disease, pregnancy, being beaten up by a drunk, violent man—would have been enormous.

Julia’s disgrace resulted in a rush of patrician men accusing their own wives of adultery, airing all sorts of suspicions and seizing the opportunity to get rid of inconvenient spouses.

The question of why Augustus believed the accusations, turning so violently against his daughter, has rarely been addressed, even though it has to be seen in the context of a longstanding (and accelerating) conflict between them. The fact that Julia was the loser doesn’t make the accusations true, and it’s clear that she had become a scapegoat for growing anxieties about female behaviour at this time; she was the most conspicuous, but by no means the only, victim of a very unpleasant moral panic, fuelled by the increasing visibility of women in ancient Rome. In a jaw-dropping development, Julia’s disgrace resulted in a rush of patrician men accusing their own wives of adultery, airing all sorts of suspicions and seizing the opportunity to get rid of inconvenient spouses.

Augustus was taken aback by the volume of the allegations, which led to dozens of other women being accused of similarly shameful sexual conduct, and he refused to act on all the charges. Maybe he realised that many were spurious. But he couldn’t be persuaded to forgive Julia, even though there are compelling reasons to challenge Seneca’s lurid summary of his letter.

© Joan Smith 2024. This text is excerpted from Unfortunately, She Was A Nymphomaniac: A New History of Rome’s Imperial Women by Joan Smith, published by William Collins.