Politics

The Return of Realpolitik

Some leaders in Europe may resist a new alliance with Trump’s America, but in a world dominated by bullies, sharp elbows and unpredictability may be what the times demand.

If the election of Donald Trump means anything, it marks the end of the liberal world order and its replacement by grim realpolitik, described by one MIT analyst as “the pursuit of vital state interests in a dangerous world that constrains state behavior.” Realpolitik may be ugly but it’s back. It is already being ruthlessly practised by China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea, but it has also been central to the Trumpian worldview since his first term. Whereas his predecessors sought engagement with other countries, Trump’s style will be to cut deals narrowly perceived as beneficial to the United States.

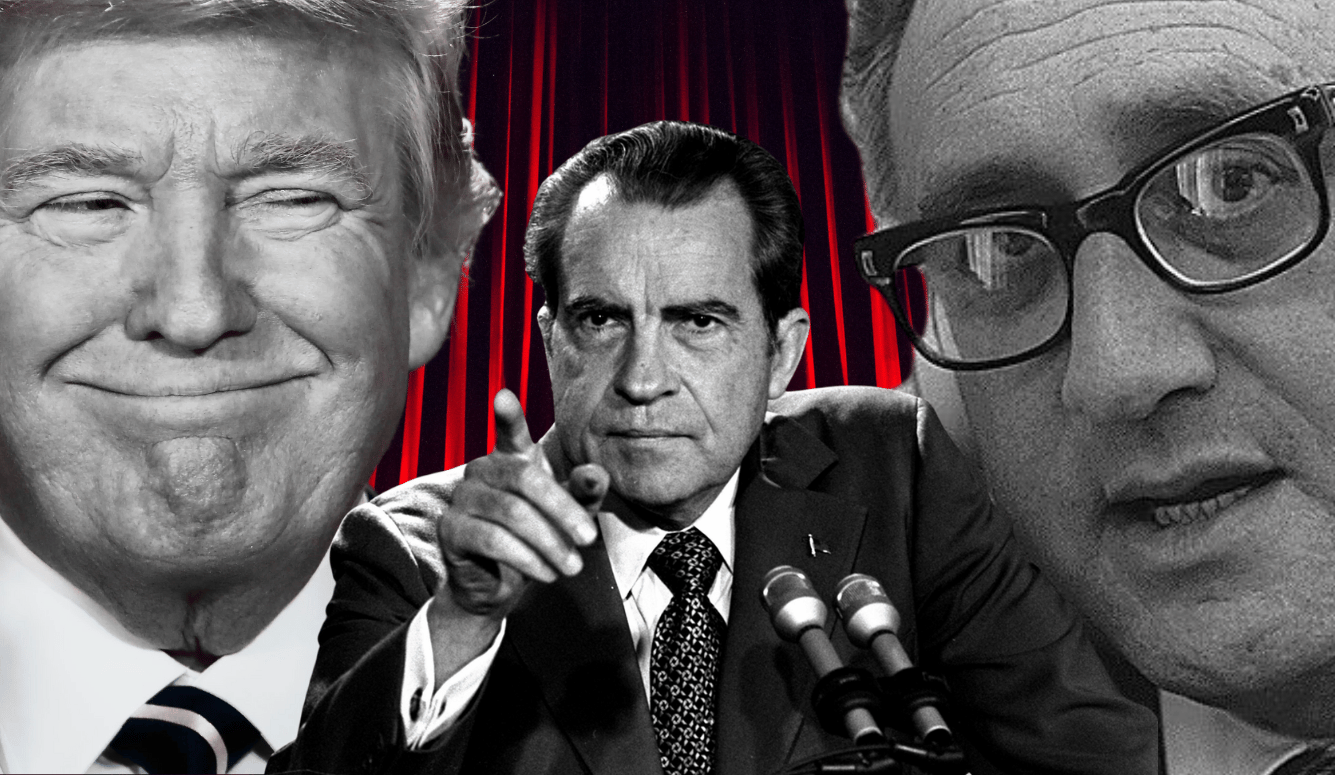

Trump will be less like Roosevelt or Reagan, who led crusades against authoritarianism, and more like Lord Palmerston, who famously remarked that his country had “no permanent allies, only permanent interests.” Other icons of realpolitik include Austria’s 19th-century minister of foreign affairs Klemens von Metternich, Wilhelmine Germany’s Otto von Bismarck, or the US’s Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger, who ditched morality in pursuit of “an equilibrium of forces.”

How the Liberal World Order Failed

The new realpolitik marks the end of an era in which politics was defined largely by ideology and religion. As in the 19th century, world events now revolve around control of markets, resources, technology, and military aptitude. In this new paradigm, institutions like the United Nations and the International Court of Justice are largely irrelevant, as are climate confabs and the high-minded pronunciamentos of the World Economic Forum.