Education

Trump and the Academic Cocoon

A New York Times op-ed by a Yale historian tries to see universities from the vantage point of an outsider. Instead, it unwittingly illustrates why universities will not self-correct without external intervention.

A full audio version of this article can be found below the paywall.

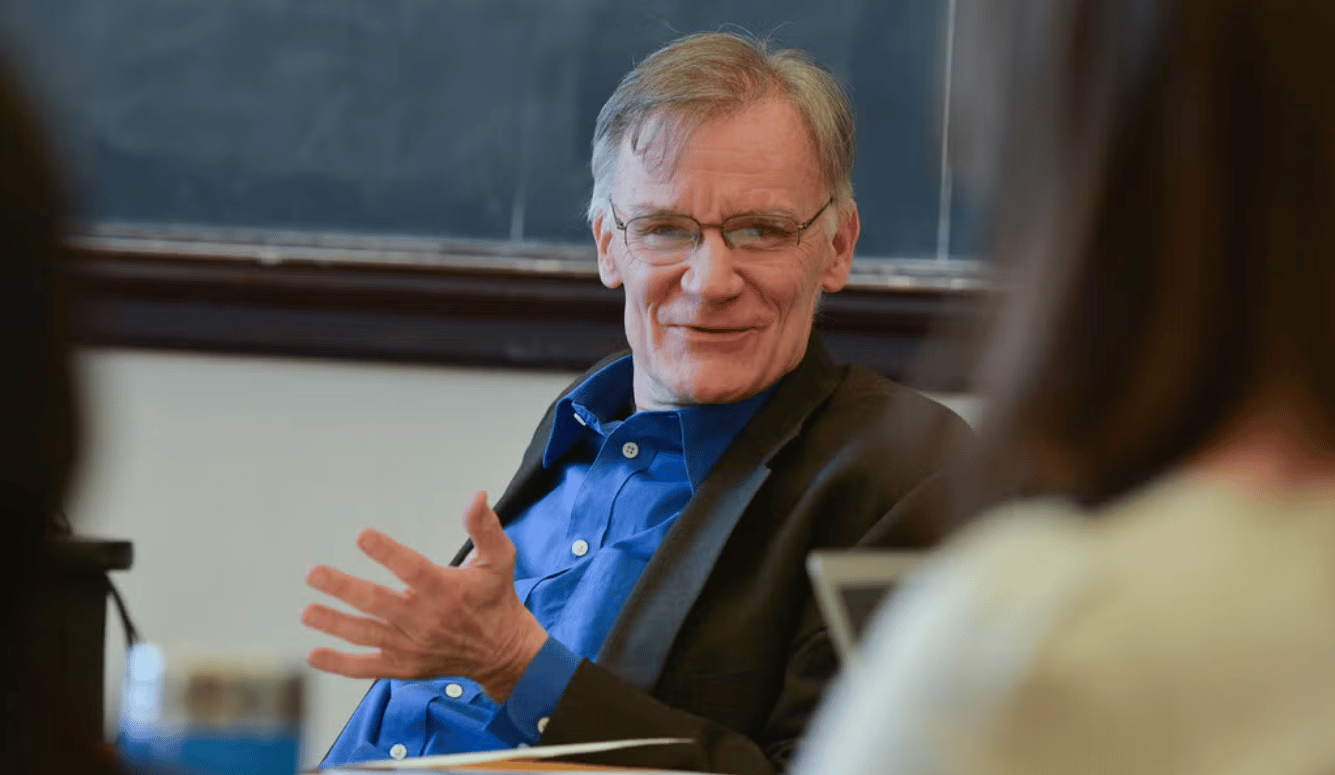

Yale historian David Blight has written an op-ed for the New York Times calling for a “reckoning” on the part of universities. Academia must grapple with its blind spots, he argues, in order to understand why blue-collar workers voted for an “authoritarian in a red tie” in the recent US presidential election. But despite these good intentions, Blight unwittingly illustrates why universities will not self-correct without external intervention.

Blight is a scholar of American race relations and the Civil War; he directs Yale’s Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition. His massive 2018 biography of Frederick Douglass won a Pulitzer Prize. He holds one of the most prestigious chairs at Yale, he’s a prominent voice on campus, and he has left a significant public footprint in non-academic historical associations. But his worldview remains stunningly parochial.