Politics

The Church at a Crossroads

Whoever becomes the next Archbishop of Canterbury will face the arduous task of uniting the now-radicalised wings of the Church of England.

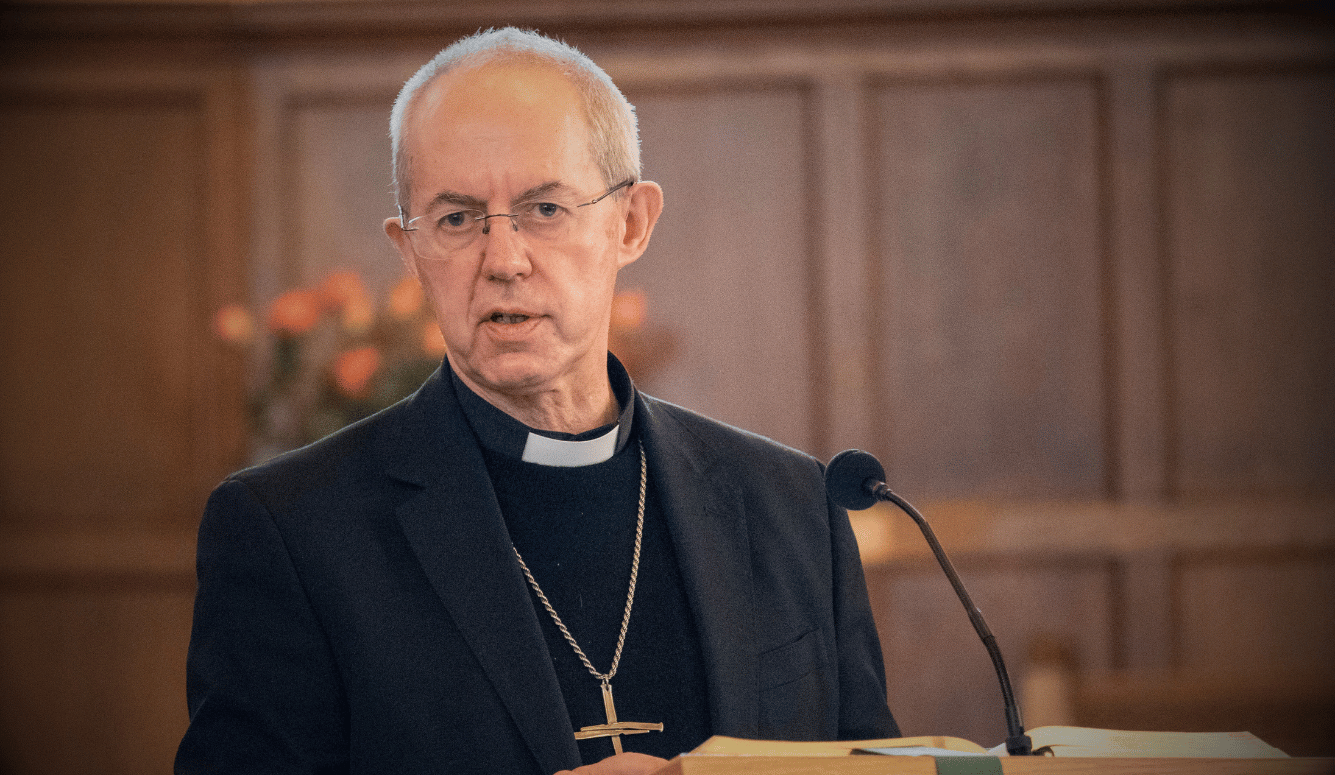

Archbishop Justin Welby, the leader of 85 million Anglicans worldwide, resigned on 12 November after eleven years in office. An independent investigation found that he had failed to take action against the late barrister John Smyth, who had supervised Church of England (CofE) boys’ camps in the 1970s and ’80s. Smyth would thrash boys’ buttocks until they bled, allegedly to deter them from masturbating.

The report into Smyth’s activities was written by barrister Keith Makin, who prefaced his catalogue of sadism by remarking, “The abuse at the hands of John Smyth was prolific and abhorrent. Words cannot adequately describe the horror of what transpired. ... Despite the efforts of some individuals to bring the abuse to the attention of authorities, the responses by the Church of England and others were wholly ineffective and amounted to a coverup.” For that concealment, Justin Welby is now on the road out of Canterbury.

Marcus Walker, rector of the medieval Church of St Bartholomew the Great in London, has emerged as Welby’s sternest critic and believes that his resignation was overdue. Conceding that Welby had delivered a “masterful” sermon following the death of Queen Elizabeth II, Walker went on to berate his former superior for his forays into political argument, which he said betrayed a “desire to create a shadow government in the church.” He concluded by reminding his successor that, “You cannot bear the weight of this calling in your own strength, but only by the grace and power of God.”

Walker believes that the primacy of the Church and the applicability of its doctrines in everyday life have been neglected. In an article for the Spectator, he discusses Libby Lane, the CofE’s first female bishop. In August 2023, when members of her congregation were torn between attending church on Sunday and watching the English women’s football team play, Lane offered the following counsel: “I know lots of people will want to watch the match live. That is fine from the Church of England’s point of view. Others will prefer to go to church and avoid knowing the score until they can watch the match on catch-up, and that is fine, too.” Walker rejects this reasoning entirely:

[A]t the risk of being a vexatious priest, there was a key factor missing from Bishop Lane’s statement, which Charles I did not miss: that church comes first. That the worship of Almighty God is, for Christians, the single most important thing we can do. Of course we were excited about the Lionesses, of course many of us wanted to bunk off church to watch them, of course the church doesn’t want to give the impression that “no honest mirth or recreation is lawful or tolerable in our religion”, but… there is an existential danger in implying that the absolute core of our religion—worship—can take a back seat when something really exciting comes along.

Many Christians, especially those clergy routinely described as conservative or evangelical, share Walker’s belief that the CofE leadership had decided to manage, rather than try to arrest, the Church’s decline. This has meant closing poorly attended churches, an approach that accelerated during the COVID pandemic. Welby was an oil-company executive for over a decade, a position that was rewarded with a six-figure salary, and this has lent credence to the view that his heart has always been in management not piety. That seems to be at least partly untrue—his early life in the church was spent among evangelicals. But in his primacy, he sought a compromise with liberals on gay unions that angered traditionalists.