Lebanon

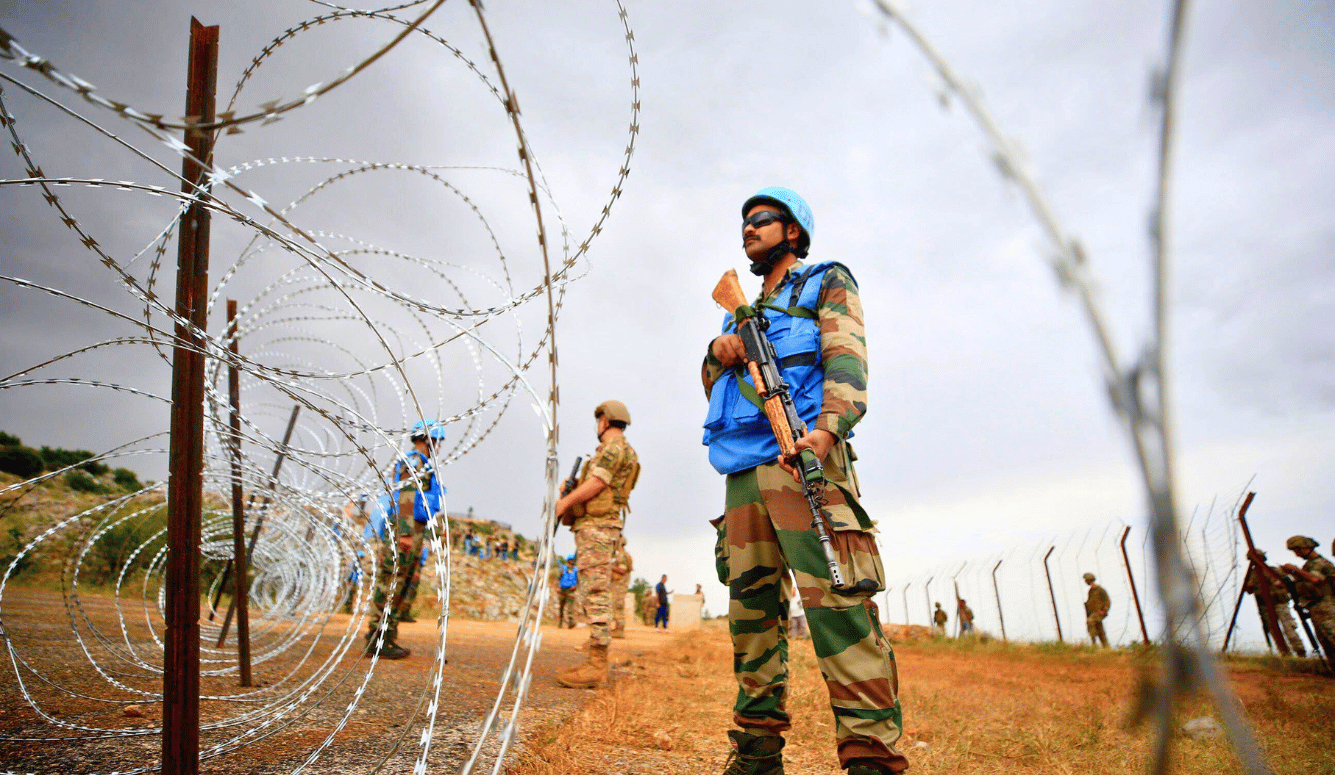

Useless UNIFIL

Were Hezbollah to disappear tomorrow, the world would be a safer place. Instead, thanks to UNIFIL’s failure to fulfil its mandate, the Middle East is on the precipice of a war of unprecedented destruction.

Since 2006, Hezbollah has been positioned right on the other side of the fence separating Israel from Lebanon. This is precisely the situation that the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon, also known as UNIFIL, was designed to prevent.

UNIFIL was established by UN Security Council resolutions 425 and 426, after Israel’s 1978 invasion of Lebanon to push terrorists away from its northern border, and was tasked with overseeing the Israeli military’s withdrawal from Lebanon, restoring peace and security in the region, and helping the Lebanese government regain effective control over the country’s south. Following the 2006 Israel–Hezbollah War, its mandate was expanded under UN Security Council Resolution 1701, and it has since been tasked with ensuring, alongside the Lebanese Armed Forces, that all weapons and military personnel south of Lebanon’s Litani River belong to either UNIFIL or to Lebanon’s own military. In other words, per Resolution 1701, Hezbollah was to vacate southern Lebanon, and UNIFIL was to work with the Lebanese army to prevent Hezbollah from rearming on Israel’s border and carrying out cross-border attacks like the one that sparked the 2006 war. Yet, the past thirteen months have witnessed unprecedented amounts of Hezbollah rocket fire at Israel, which has forced the country to launch a ground incursion into Lebanon. Clearly, UNIFIL has failed.