Israel

The Shifting Sands of War

A detailed look at the past year of war between Israel and its adversaries, as the battleground has shifted from Gaza to Lebanon and now to Iran.

As I write, Israel has just responded to the two massive Iranian missile attacks of 14 April and 1 October, and, more generally, to the year-long assault by Iran’s terrorist proxies that began with Hamas’s surprise assault on southern Israel on 7 October 2023. Israel’s strike was delivered in three waves by an armada of 140 Israeli aircraft. It was limited to Iran’s air defences—consisting principally of Russian-made S-300 and possibly S-400 surface-to-air missile (SAM) batteries—and military-industrial plants—missile, drone, and rocket factories—as well to Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps ballistic missile bases and storage sites —in line with Washington’s insistence that Israel spare Iran’s economically crucial oil production facilities and nuclear installations. If drone factories were hit, as is likely, this may affect the course of the Russian–Ukrainian war too, as Russia’s war-making is partly reliant on imported Iranian drones. All Israel’s aircraft returned safely to base—Iran’s claims to the contrary notwithstanding. Iran has also downplayed the destruction wrought by Israel’s F-15s, F-16s, F-35s, and suicide drones. Within a two-hour period, the Israel Air Force (IAF) hit some twenty sites stretching from Tehran in the north to Iran’s “oil capital” Abadan, near the Persian Gulf.

How Iran responds will determine the future of the Iran–Israel conflict—though it will probably not affect—at least not directly—the Israeli campaigns against Hamas in Gaza and Hezbollah in Lebanon, where Israeli ground forces and the IAF continue to degrade the terrorist organisations’ military capabilities.

So far, Iran has publicly dismissed the Israeli strikes as ineffective, statements that might give Tehran an excuse to refrain from responding militarily, as it promised to do over the past weeks, should Israel attack. But if Iran does respond with a further missile strike on Israel—or attacks on Israeli or Jewish targets around the world or by rushing toward production of nuclear weaponry —the IDF can be expected to target Iran’s oil installations and nuclear sites in a follow-up strike, in an effort to cripple the country’s economy and remove the threat of nuclear weaponry falling into the hands of the Ayatollahs. This action will probably not take place until after the US elections.

For the past two decades, Israel’s prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, has warned that nuclear weapons in the hands of Iran would pose an existential threat to the Jewish state, given Iran’s oft-declared policy goal of destroying Israel. The war launched by Tehran and its proxies last October has at last given Israel the opportunity and legitimacy it needs to destroy the Iranian nuclear project. But for the moment, Washington’s fear of becoming embroiled in yet another war in the Middle East, after its protracted failures in Iraq and Afghanistan, has stayed Israel’s hand. Biden and Harris have also pressed Israel to refrain from attacking the Iranian oil installations for fear of provoking a major spike in fuel prices that could jeopardise a Democratic victory on 5 November.

Whether Iran will respond with a renewed missile attack on Israel, which would raise the prospect of an open-ended missile war of attrition between the two countries, remains to be seen. Meanwhile, Israel appears to have the upper hand in its asymmetric fight against Iran’s proxies, since the military capabilities of both Hamas and Hezbollah have been substantially degraded over the past twelve months.

Nonetheless, this war is unlike any Israel has endured these past seventy years. Most ended in clear-cut decisions. Israel won its first war, in 1948, against the aggressing Palestinian militias and the surrounding Arab states, and the Jewish state was born. Israel won its seven-day war against Egypt in the so-called Sinai Campaign of 1956 even more decisively. And then Israel won the 1967 Six-Day War against the Egyptian-Syrian-Jordanian coalition with astonishing conclusiveness, in the process occupying the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip, as well as the Sinai Peninsula and the Golan Heights. Six years later, in October 1973, in the last of the conventional wars, the IDF beat attacking Egyptian and Syrian forces: a victory that ultimately resulted in the Israel–Egypt peace treaty of 1979, when Egypt’s President Anwar Sadat decided that it was time to pull Egypt out of the struggle against the Jewish state.

But then things got tricky. The Palestinians resumed their battle against Israel, entrenching themselves in southern Lebanon, from whence they periodically rocketed and raided the Galilee. As a result, Lebanon became a major battleground. In June 1982, the IDF invaded southern Lebanon and drove the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) out of the country. The Shi’ite villagers initially greeted the victors with showers of rice, but the Israelis outstayed their welcome and a fundamentalist Shi’ite organization, Hezbollah, soon emerged and, following an 18-year-long insurgency, drove the IDF back to the Lebanon–Israel border. This border had been agreed upon in 1923 by Great Britain and France, which held mandates over Palestine and Lebanon respectively. The contours of the border were re-affirmed in the Israel–Lebanon General Armistice Agreement of March 1949.

But then Hezbollah over-reached. Declaring that the destruction of Israel was its ultimate goal, the organisation resumed its periodic cross-border rocketing and terrorist raids. In 2006, the IDF invaded southern Lebanon yet again, in what Israelis now call the Second Lebanon War. But this action was poorly planned and executed and the outcome was humiliating for the IDF. Though they mauled Hezbollah, the Israelis were forced to withdraw to the border. Over the next 17 years, Hezbollah was able to make a recovery. The organisation was heavily subsidised and re-armed to the teeth by Iran. This set the stage for the current conflict in Lebanon.

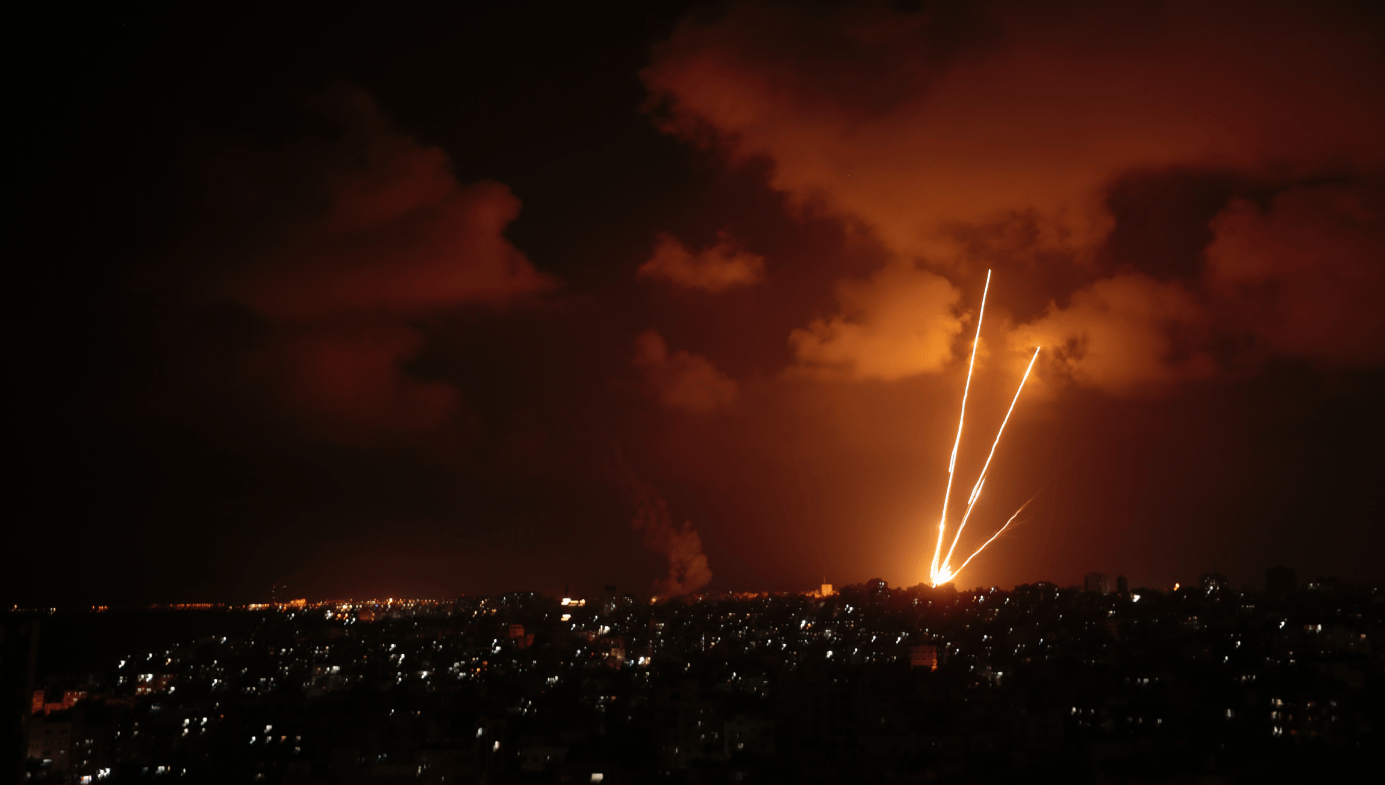

Meanwhile, Hamas, which ruled the Gaza Strip, was equally dedicated to Israel’s destruction. On 7 October 2023, Hamas invaded southern Israel, slaughtering 815 Israeli civilians and more than 350 soldiers; taking 251 hostages—most of them civilians—ranging in age from 3 months to 89 years; and raping Israeli women and girls (and probably some men) before killing them. Hezbollah renewed hostilities against Israel the following day in solidarity with Hamas. On 8 October, Hezbollah began rocketing northern Israel’s border settlements and threatened the Galilee with invasion. With the help of a military force of some 50–80,000 fighters and an arsenal of tens of thousands of rockets, some of which could reach as far as Tel Aviv, Hezbollah assisted Hamas by pinning down two IDF divisions along the northern border. Israel responded with air and artillery strikes against Hezbollah strongholds in the Shi’ite villages and towns of southern Lebanon. Thus began Israel’s third Lebanon war, which is still ongoing.

During the following eleven months, the two sides traded shot and shell across the border. But both sides severely limited their war-making. Each mainly targeted the other’s border-hugging combatants and bases, and on both sides civilian casualties were few. By mid-September 2024, the IDF had killed around 500 Hezbollah fighters, including many local commanders, while some 50 Israelis had died, most of them soldiers. Most of the inhabitants of the border-hugging Israeli villages and towns, some 70,000 souls, were ordered by the government to move southwards, out of harm’s way, and were installed in cramped hotel rooms or moved into the houses of relatives and friends. This was Hezbollah’s main strategic accomplishment during the war. The border-hugging Shi’ite villages of southern Lebanon also emptied out and many non-Shi’ite villagers fled northward. The IDF refrained from attacking Hezbollah strongholds in Beirut and the Bekaa Valley in eastern Lebanon, while Hezbollah refrained from rocketing Haifa—northern Israel’s largest city—and the centres of Jewish population in and around Tel Aviv. Much of the housing on both sides of the border was badly damaged by IDF bombs and shells and by Hezbollah rockets, Kornet anti-tank missiles, and suicide drones.

But this Lebanon war was only one part of the wider fundamentalist Muslim onslaught against Israel, which was orchestrated, financed, and armed by Iran. The simultaneous assault against the Jewish state over the past twelve months has involved not only the Sunni Hamas in Gaza and the Shi’ite Hezbollah in Lebanon, but Shi’ite militias in Syria and Iraq, as well as various Palestinian guerrillas and terrorists from the West Bank. The pro-Iranian militias in Syria, Iraq, and Yemen occasionally launched suicide drones and ballistic missiles at southern and central Israel, while the Houthis rocketed shipping passing through the Bab al Mandab Straits that connect the Red Sea to the Indian Ocean, thereby blocking Israeli and international shipping headed for or emerging from Eilat and the Suez Canal, By halting international shipping, the blockade damaged Egypt’s economy as well. But from October 2023 to August 2024, the conflict was focused on the Gaza Strip.

Hamas launched its 7 October attack with the aims of hurting the Jewish state and freeing thousands of its fighters from Israeli prisons in a prospective hostage–prisoner exchange. The Gazan terrorist group headed by Yahya Sinwar—himself a former Israeli prisoner—probably hoped that the attack would thrust the issue of Palestinian statelessness and refugeehood back onto the international agenda and disrupt a mooted agreement between Israel and Saudi Arabia. Washington had hoped that such an agreement would continue the process begun by the signing of the 2020 Abraham Accords, which established peace and diplomatic relations between Israel and three Sunni Arab countrie—the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and Morocco—an expansion of the Israeli–Egyptian peace treaty and the Israeli–Jordanian peace treaty of 1994. Sinwar for his part was probably counting on Iran and Hezbollah—and possibly other Muslim groups or states—joining the fray, even though, in the preceding months, Iran and Hezbollah’s leader Hassan Nasrallah had declined to join Hamas’s prospective attack. It is also likely that Sinwar correctly predicted that Israel would react ferociously and end up killing many Gazan civilians, among whom the Hamas fighters were embedded, which would turn public opinion in the West against Israel—a pattern that had occurred in previous bouts of Hamas–Israel violence.

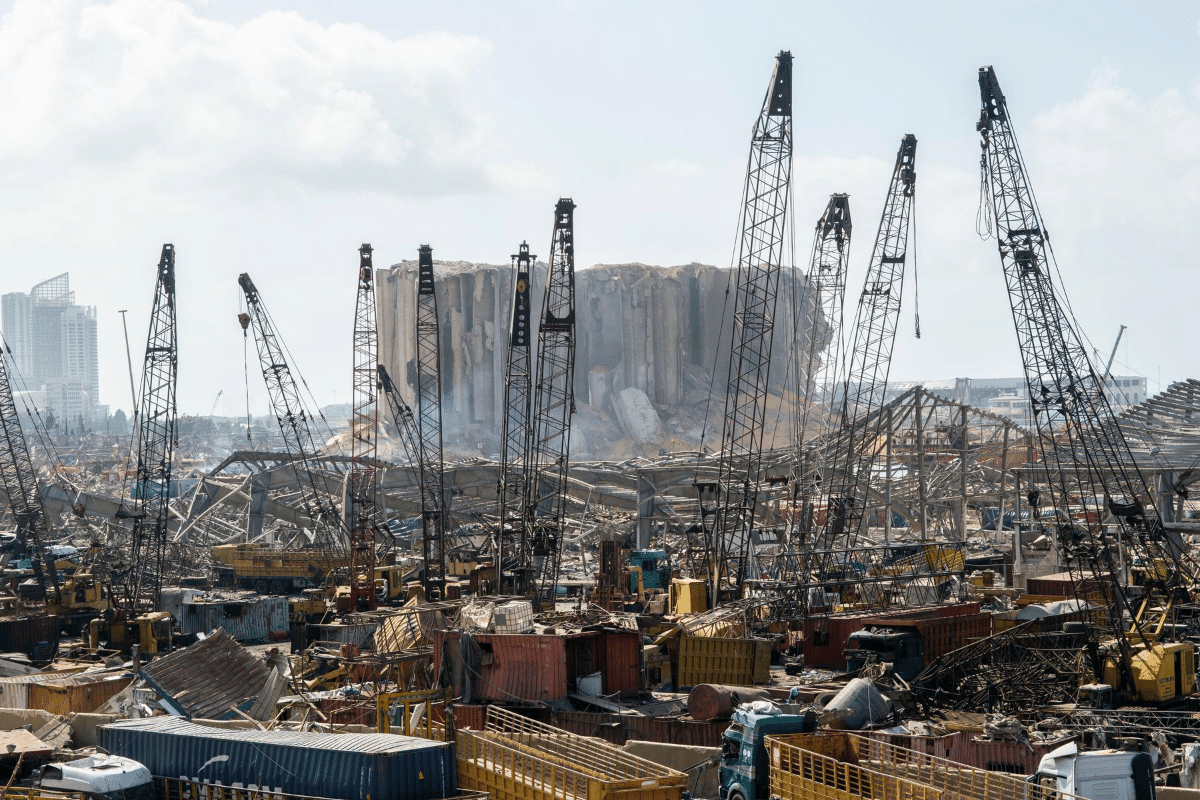

Israel had no choice but to respond aggressively. On 8 October, after battling with and killing the Hamas raiders inside Israel, the IDF launched a massive campaign of bombing and shelling directed against Hamas strongholds, arsenals, and hideouts in the Strip. The Hamas fighters would typically hide in the vast tunnel system they had constructed under Gaza’s cities and in and under hospitals, schools, universities, and mosques. Though its intensity has been gradually reduced, the air campaign against Gaza continues to this day. Tens of thousands of buildings have been levelled—and many Gazans have died. Roads and other infrastructure have been destroyed beyond recognition. In October 2024, the Hamas-controlled Gaza Health Ministry announced that 42,500 Gazans had been killed over the past year, but it did not differentiate between combatant and civilian dead. IDF sources have cast doubt on this figure and in any case claim that about half of Gaza’s dead were Hamas and Islamic Jihad fighters.

On 27 October 2023, the IDF followed up its aerial campaign with a ground invasion of the Strip by armoured divisions, starting in the northern towns of Gaza City and Beit Hanun. After putting up some resistance, most of the Hamas fighters went underground, fleeing into the vast tunnel system constructed over the previous two decades. But some remained above ground, hiding in the apartment buildings that housed their siblings, children, parents, and other relatives, who supported and sustained them and helped conceal their weapons. Israel declared that its aims were to destroy Hamas as a military and governing organisation and to free the hostages—though doubtless the Israeli response was also motivated by revenge and a desire to so traumatise the Palestinians that another 7 October would not occur.

Hamas denied the civilian population access to the 700 km tunnel system, which is made of reinforced concrete, with tunnels located 10, 20, and 50 metres underground. The civilians were left stranded above ground, with neither air raid shelters or bunkers to protect them. The tunnel system was formidable—much more extensive than IDF intelligence had known. It was built for a long siege and contained vast stores of food, fuel, arms, and ammunition. Some tunnels even contained cages for prospective hostages.

Over the following eleven months, IDF special forces, aided by sniffer dogs and drones, sought out the shafts leading from Gaza’s residential buildings and public structures down into the tunnel system, and ventured inside, braving booby-traps and sentries. The raiding troops were hampered by the knowledge that Israeli hostages served as Hamas’s human shield—as indeed did Gaza’s civilian population. Nonetheless, the troops cleared some of the tunnels and blew them up. But the task of destroying the tunnels proved costly and Sisyphean, as the Hamas fighters fled from one tunnel to the next, periodically emerging on the surface, where they sniped at the rearguard of advancing IDF troops with rifles and rocket-propelled grenades and placed IEDs (improvised explosive devices) in their path. IDF generals have said it would take years to destroy the entire tunnel system.

Meanwhile, tens of thousands of Gazan civilians took shelter in the Strip’s hospital compounds and school buildings, as did Hamas fighters and commanders. IAF fighter-bombers, guided by all-seeing drone cameras and sensors, periodically bombed these sites, usually killing civilians as well as their armed targets.

From October 2023 to January 2024, IDF columns over-ran the northern third of the Strip and drove most of its inhabitants southward toward Khan Yunis and Rafah. The IDF then established an east–west line, the Netzarim Axis, along Wadi Gaza, running from the Israeli border to the Mediterranean, thus cutting the Strip in two. Later, the IDF over-ran the Strip’s second largest town in the south, Khan Yunis, Sinwar’s birthplace.

The IDF spent too much time in the areas it had occupied, however: raiding the odd renewed urban concentration of Hamas fighters here; targeting and killing a Hamas battalion or brigade commander or demolishing an underground tunnel there. But finally, under pressure from the 70,000 displaced Israelis from the northern border settlements, the government switched focus and began shifting brigades from the south to the Lebanese front. The IDF had been meticulously preparing for this since 2006 ; by mid-September 2024, it was ready, and the offensive against Hezbollah was unleashed. It began with a brilliant Mossad operation that involved an industrial-grade attack using booby-trapped pagers and walkie-talkies with miniature bombs that simultaneously exploded in two waves, severely injuring thousands of Hezbollah operatives, many of whom lost eyes, hands, and fingers. The IDF followed this up with an air assault against major rocket storage sites and command centres, together with precision strikes against Hezbollah’s military commanders, who were ensconced in “safe” apartments and underground bunkers around Beirut. The operation culminated in the assassination of Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah on 27 September. On 3 October, his prospective heir, Hashem Sefieddine, was also killed. Air raids knocked out Hezbollah infrastructure in the Bekaa Valley and the main Hezbullah stronghold in Beirut’s Dahiya neighbourhood, as well as in southern Lebanon. The gloves were off.

Then, on 1 October, four IDF divisional task forces crossed into southern Lebanon and began cleaning out Hezbollah fighters and their pre-prepared weapons and munitions storage facilities in the Shi’ite villages along the border, inch by inch, destroying tunnels and bunkers that were equipped as forward jump-off positions for a planned Hezbollah ground offensive into the Galilee that would have resembled Hamas’s 7 October onslaught. IDF spokesmen have expressed surprise at the extent of Hezbollah’s preparations in the border-hugging villages. It appears that the villagers were paid a monthly “rent” in exchange for hosting Hezbollah fighters and storing their equipment. In some villages, two out of every three houses were found to contain floor-to-ceiling weapons and ammunition caches. The overgrown, forested areas between the villages were also sprinkled with Hezbollah firing positions, trenches, tunnels, bunkers, and weapons depots. IDF infantrymen backed by tanks, drones, and helicopters, were occasionally challenged by Hezbollah squads, which took a serious toll on the IDF soldiers. But most Hezbollah fighters fled northward. So far, more than a dozen Hezbollah men have been captured.

Hezbollah responded strategically to Israel’s invasion by increasing the number of projectiles it fired across the border daily, and by extending their reach all the way to the Haifa-Hadera and Beit Shean Valley areas of northern Israel. Heavier rockets were occasionally lobbed at the Tel Aviv area. Most of the projectiles were shot down by Israeli Iron Dome interceptors or landed in empty fields. A few missiles got through, claiming casualties and damaging buildings, but most Israelis, duly warned by an efficient public alert system, avoided harm by taking shelter in their “safe” rooms and in public shelters. Hezbollah maintains that its targets were Israeli military and intelligence posts—and, indeed, one suicide drone hit a Golani Infantry Brigade camp as the personnel were at supper in a large hall, killing four and wounding sixty. Hezbollah also tried to avenge its leaders’ deaths by targeting Netanyahu’s private residence in the coastal town of Caesarea—where Roman procurator Pontius Pilate resided two thousand years ago—with a drone. It caused only minor damage. Benjamin and Sarah Netanyahu were in Jerusalem at the time. Netanyahu publicly blamed Iran, but Tehran quickly claimed that it had no hand in the attack.

But in recent weeks, the Israeli police and Shin Bet security service have arrested more than a dozen Israelis who were recruited by Iranian intelligence. One of the cells apparently sent Tehran photos of the assailed Golani dining hall prior to the drone attack and of the Nevatim IAF base before and after the Iranian attack on it on 1 October. Most of those Israelis detained, and now on trial for treason, were Jews, some of them immigrants from Azerbaijan. Some of the recruits were tasked with assassinating military figures and scientists—presumably in response to Israeli assassinations of top IRGC commanders and Iranian nuclear scientists over the past decades. The recruits were paid, sometimes in crypto currency, specific sums for specific chores, ranging from hundreds of dollars for photographs to tens of thousands for a successful assassination.

During the year-long counter-offensive against Hamas, the IDF and Shin Bet gradually killed off Hamas’s regional, brigade, and battalion commanders, degrading the terrorist “army” of some 30–40,000 fighters into an uncoordinated collection of guerrilla squads waging hit-and-run war from their tunnels. The Hamas fighters periodically fired off rockets at Israel, though by October 2024, their rocketing capabilities had been reduced to almost zero.

In May–June 2024, defying President Biden’s cautions, the IDF occupied the Philadelphi Axis that runs the length of the Gaza–Egypt border, along with the border crossing and the town of Rafah. At that point, the Israelis had yet to snag Sinwar, the mastermind, leader, and symbol of 7 October. It appears that they had been hot on his trail a number of times, but each time he escaped southward through the tunnel network. But on 17 October, an IDF patrol spotted three figures wandering among the ruins of the Tel al-Sultan neighbourhood of Rafah and engaged them, while a tank fired shells at a second-storey apartment. A surveillance drone examined the site and then Israeli troops entered to find—to their surprise—the fresh corpse of Yahya Sinwar, minus a hand. He had a great deal of cash and a number of passports on him. Perhaps he was making his way to the Egyptian border or to a refugee encampment in the Mawassi area.

Washington announced that an opportunity had opened up for a mediated Israeli–Hamas negotiation to end the war in Gaza while ensuring Hamas’s release of the “101” Israeli hostages in exchange for prisoners. The Israeli authorities estimated that perhaps half the hostages were still alive: many had died in captivity—perishing from sickness, murdered by their captors, or inadvertently killed by friendly fire. It is unclear whether any progress will be achieved in the near future regarding a possible hostage deal or an end to the Hamas–Israel hostilities. With Sinwar’s death, there appears to be no Hamas leader who could actually make a deal with Israel. And Hamas’s traditional position—which the Hamas leaders lodged in Qatar have continued to enunciate—is that a hostage release can only proceed if Israel agrees to completely withdraw from the Gaza Strip and end its offensive, a position rejected by Netanyahu, who argues, with some justice, that Israeli withdrawal would mean a Hamas resurgence.

It is too early to gauge the long-term effects of this war—especially since it is not yet over. But some interim conclusions can already be drawn.

The 7 October assault certainly traumatised the Israeli population—even more than the surprise Egyptian-Syrian attack on Sinai and the Golan Heights on 6 October 1973. More Jews died on 7 October than on any day since the end of the Holocaust in 1945. And the trauma was exacerbated by the mass rapes and the long-term suffering engendered by the hostage situation. Although 130 of the hostages were released in November 2023 in exchange for hundreds of Hamas prisoners held by Israel and a short truce, more than 100 Israeli hostages—some of them presumed dead—remain in Hamas’s hands. The horror caused by the continued captivity of many of the hostages, under execrable conditions, in which the women are vulnerable to rape, has been compounded by the continuous, day in, day out, coverage of the subject by the Israeli media.

Moreover, the continuing war in Gaza and along the Lebanese border since 7 October has claimed the lives of another 400 or so Israeli soldiers and of a handful of civilians, adding a further layer of trauma for the many families directly and indirectly affected.

Some 130,000 Israelis were displaced from the areas adjoining the Gaza Strip and the northern border on 7–8 October 2023 and continue to live in internal exile. This is the first time Israelis have been forced out of their homes since the 1948 War. These refugees are still stuck in hotel rooms or in the houses of friends and relatives and it is unclear when they will be able to return home. This experience alone must cause psychological trauma, if only among the displaced and their families.

But the Israelis are not the only ones to have suffered trauma over the past twelve months. The IDF assault on the Gaza Strip caused perhaps as many as 20,000 civilian deaths and many more injuries—and many of the dead and wounded were children—as well as vast material destruction and the enforced displacement of most of Gaza’s 2.3 million inhabitants. Indeed, many families ended up being displaced twice or even three times as the IDF ground forces advanced from place to place, ordering massive civilian evacuations as they went. Most of the Strip’s population now live either in makeshift tent encampments amid the rubble of devastated cities, in the Mawassi agricultural zone, or in ruined buildings. Palestinian spokesmen have described what has happened as a “second Nakba,” the first being the 1948 displacement and refugeedom of the parents and grandparents of most of the currently displaced Palestinians. This mass experience of death, injury, and displacement, now entering its second year, has no doubt left much of the Strip’s population suffering from acute trauma. Many thousands of orphans now clutter the hospital compounds and tent cities around the Strip.

Without a doubt, Lebanon’s Shi’ite minority, who form Hezbollah’s political base, have undergone a similar experience since October 2023. Though very few civilians have been killed, many have been displaced from their villages and towns in southern Lebanon, from Beirut’s Dahiya neighbourhood, and from the towns and villages of the Bekaa Valle, especially since the start of Israel’s massive aerial bombardment campaign in September 2024. The Lebanese government claims that at least one million Lebanese—a fifth of the country’s population—are now homeless, living in empty school buildings and hospital compounds or on the streets of Beirut. Hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees, who fled to Lebanon during the recent Syrian civil war, have now crossed back into Syria, alongside Lebanese refugees, in the hope of finding safety. Come winter, their situation will be dire. According to the Lebanese government, more than 2,000 Lebanese civilians have died over the past year—though these casualty figures are relatively low, due to the Israeli evacuation orders issued to villages and urban neighbourhoods, even to individual high-rises, prior to IDF ground and air assaults.

A further casualty of this war has been Israel’s international reputation. The ongoing war, as projected onto electronic media screens in the West, has undermined the Jewish state’s status as a humane polity. Israel’s Jews—and by extension Jews everywhere—have turned from victims to victimisers in the eyes of large parts of the Western public. Day after day, western TV audiences have been shown the dead or injured bodies of Arab women and babies, victims of Israeli ground operations and aerial strikes. These audiences are never shown dead or injured Hamas or Hezbollah fighters (or live ones for that matter)—so to them, it appears that Israel is simply savaging Arab civilians, not fighting a war. Israel has always preferred not to show its own casualties, partly out of concern for their families—and about half of those casualties since 7 October have been combatants.

Over the past year, most Western governments have shown some understanding of the dilemmas facing Israel and the problems raised by fighting terrorist groups embedded within civilian populations, and appreciate that the current hostilities in Gaza and Lebanon began with Hamas’s savage attack and Hezbollah’s subsequent rocketing of Israel. Yet, for many ordinary people, the memory of 7-8 October has faded, while images of Arab suffering have dominated TV screens. In addition, weekly demonstrations by noisy pro-Palestinian crowds—often containing pro-Hamas and -Hezbollah and openly antisemitic elements—on the streets of Western cities have often driven governments to ambivalent posturing, as when US Vice-President Kamala Harris enjoins Israel to desist from this or that action. In Western European states like France, Germany and the United Kingdom, the presence of large Muslim minorities, with internal political clout and a very vocal anti-Israeli stance, has resulted in similar ambiguities, including calls for the “immediate” Israeli suspension of hostilities—when such a suspension, while the IDF is midway through its counter-offensives, can only serve the purposes of Hamas and Hezbollah.

This has resulted in tensions in Israel’s relations with a number of European states, including France and Ireland. Last week, French President Emanuel Macron called for arms embargos against Israel and blocked Israeli participation in an important French arms fair. Italy and Great Britain have already imposed undefined arms embargos against Israel. Four Latin American states—Belize, Nicaragua, Bolivia, and Columbia—have severed diplomatic relations with Israel or threatened to do so. The United Nations, with its large Muslim voting bloc, has become a prominent forum for anti-Israel argumentation and resolutions, though so far the United States has used its veto to prevent condemnation of and sanctions against Israel in the critical UN Security Council.

But in the run-up to the 5 November elections, Israel has lost traction among Democratic Party politicians due to fears that Muslims in key battleground states, such as Michigan, may withdraw their votes from the party. But so far the United States has continued to supply the crucial munitions Israel requires (sans one suspended shipment of dumb bombs). It is unclear what will happen to the “special” Israel–US relationship after 20 January 2025, no matter who wins the election. But meanwhile the very pro-Zionist Joe Biden remains America’s president and despite his personal animosity toward the mendacious and largely incompetent Netanyahu, he has weathered the storm and the relationship between the two countries remains stable and productive, especially at the level of defence ministries and armies. America has Israel’s back, Biden assured the Jewish state at the start of the war, and this remains especially true in all that concerns Iran. In recent weeks, Washington sent Israel THAAD batteries, with their US Army operators, to shore up Israel’s air defences against future Iranian missile assaults, while many American naval and air units have arrived in the waters and air bases surrounding Iran—all of which delivers a firm warning to Tehran.

Israel’s economy has been severely damaged by the war. Tourism and foreign investments, especially in Israel’s high-tech sector, have almost completely stopped. Nehemia Strassler, the highly respected economic editor of Haaretz, Israel’s leading daily, has estimated that the war has already caused some $5 USD billion in damage to buildings and infrastructure, especially along the borders with Lebanon and Gaza, and further damage, which the government will have to repair, is likely if the war continues. Strassler has estimated that the Israeli economy has suffered a GDP loss of some $20 billion USD this past year and will suffer a similar loss next year if the war continues for a further twelve months. This will translate into a major reduction in government provision of public goods and services, including in health care and education. In addition, government expenditure on war-making—on weaponry that needs to be replaced and on munitions stockpiles, and payments to the hundreds of thousands of reservists who have been called up for extended periods, entailing a major loss in production—is incalculable. On 25 October 2024, Strassler estimated that, all told, if it continues, the war will end up costing Israel close to $100 billion. How much of this the United States will cover—under Joe Biden, Donald Trump, or Kamala Harris—is anyone’s guess.

The war has also had demographic impacts. Thousands of young Israelis—the exact numbers are unclear—have left Israel over the past year and thousands more are expected to leave in the coming year. Some are bent on immigration to the West—Berlin and the Anglo-Saxon countries are favourite destinations—while others may simply have gone abroad for a breather and will decide on their futures later. The wave of emigration began during the year preceding 7 October, after the Netanyahu government attempted to subvert Israel’s judicial system—and, in effect, Israeli democracy—with a so-called “judicial reform,” which brought hundreds of thousands of Israelis out onto the streets in protest. Israeli economists fear that this exodus, which includes many young, middle-class, university-educated Israelis, may severely damage the economy.

And the IDF now faces a severe manpower problem. The country’s ultra-Orthodox communities, which represent 15 percent of the population and field two indispensable parties in Netanyahu’s coalition, persist in refusing to send their sons to the army. Secular and moderately religious 21–40-year-old reservists have been serving for 100, 200 and even 300 days this past year, away from their families and workplaces. This is beginning to sap their will to continue to serve. According to one report, while 130 percent of reservists showed up for duty when called at the start of the war, the figure has now dwindled to 60 percent.

But, perversely, the war, has gradually strengthened Netanyahu’s coalition government, even though the prime minister and his obedient—even servile—ministers are seen by most Israelis as responsible for the disaster that befell Israel on 7 October. Though pressed, he has persistently refused to acknowledge responsibility for what happened. Nor has anything that happened that day or since persuaded any of the Netanyahu coalition’s 64 Knesset members (the Knesset has 120 seats) to defect and cross the aisle. Indeed, last month Netanyahu’s Knesset majority increased to 69 when five opposition members joined the coalition.

All opinion polls during the months following the Hamas attack showed a major decline in public support for Netanyahu and his right-wing coalition partners and predicted his defeat if early elections were held (as it is, elections are scheduled for 2026). But over the months, a majority of the public have fallen into line with Netanyahu’s message that the country cannot afford elections during a war and that no commission of inquiry should be appointed to investigate the disaster, and most Israelis, it appears, have also accepted Netanyahu’s deflection of blame to the army and the security services for failing to anticipate and adequately respond to the Hamas onslaught on 7 October. The fact that, over the course of his 15–16 years of premiership, Netanyahu has actively enabled the strengthening of Hamas—most obviously by facilitating Qatar’s transfer of hundreds of millions of dollars to the organisation and by arguing that Hamas had been “neutralised” and would not attack Israel—has somehow been ignored by his supporters. Netanyahu’s unspoken pro-Hamas policy was geared towards weakening that organisation’s rival, the Ramallah-based Palestinian Authority, led by the Fatah Party—because Fatah, at least officially, promoted negotiations with Israel designed to achieve a two-state solution, while Hamas—like Netanyahu—opposes a two-state compromise, although—unlike Netanyahu—it advocates Israel’s destruction as the sole “just solution” to the conflict.

The savagery of 7 October has pushed Israelis rightward, a phenomenon most obvious among the young. The glissement à droite is nowhere more apparent than in the West Bank, where, over the past year, right-wingers, most of them under thirty, connected with the settlement enterprise and the two extremist parties in the ruling coalition have greatly increased the number of “wild”—i.e. non-government-authorised—settler outposts. At the same time, the past two years, since the establishment of the present Netanyahu government, have seen a major increase in settler violence against Arab villagers, sometimes in response to Arab terrorist attacks on settlers. Masked settlers have beaten and killed Arab villagers, burned Arab homes, and prevented Arabs from tending to their fields and olive trees. Israeli troops that have witnessed these events have almost invariably failed to intervene and the Israeli police, under Minister of National Security Itamar Ben-Gvir, the most prominent among Israel’s right-wing ministers, routinely do nothing. The Right views the settlers’ behaviour as bolstering the settlement enterprise and pushing the Arabs towards eventual emigration—a strategy ultimately designed to facilitate Israeli annexation of the West Bank.

The war has also affected the surrounding Arab states. Last month’s expansion of the conflict into a full-blown Israeli–Hezbollah war has shaken up Lebanese politics, over which, up until now, Hezbollah has had a stranglehold, rendering the other political factions subservient to the Shi’ite fundamentalists’ every whim. Now, the massive destruction wrought in southern Lebanon, which also contains Sunni, Druze, and Christian inhabitants, as well as in multi-religious Beirut, together with the massive displacement of inhabitants, have led the country’s non-Shi’ites to begin to vent their displeasure at Hezbollah. Hezbollah is seen as having provoked the war with Israel and although most Lebanese dislike Israel, they do not appreciate being dragged into a conflict on behalf of the Palestinians and Iran. Both Israel and the West are now quietly urging Lebanon’s factions to come together and seriously curtail Hezbollah’s power—and perhaps even disarm that organisation, in line with UN Security Council Resolution 1701, from 2006. Whether the war will ultimately generate a major reshuffle of Lebanese politics and a revamped version of 1701—a resolution that was never implemented and contained no mechanism for implementation—is up in the air. But so long as Hezbollah retains tens of thousands of foot soldiers, most Lebanese will continue to be in their thrall, even if they are only armed with light weapons.

Over the past year, both Egypt and Jordan have been fearful that the war might spill over into their own countries. Jordan fears that Islamic passions might engulf the country and pose a challenge to the Hashemite monarchy. Egypt fears that Israeli pressure on the Gazan population will result in hundreds of thousands of Palestinians being driven into Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula, thus confronting Cairo with a major economic and humanitarian problem.

As for the terrorists, the year-long fight has left Hezbollah and Hamas in shambles. Both organisations have lost most of their weaponry and weapons-producing workshops. Hamas lost its military commanders and most of its foot soldiers—though doubtless new ones have been recruited from among Gaza’s battle-eager youngsters over the past few months—and its “governmental” institutions no doubt suffered major damage. Similarly, Hezbollah was decapitated and lost many of its fighters. Indeed, at the time of writing, neither organisation has replaced the bulk of its commanders and command structures. In late October 2024, the IAF also pulverised Hezbollah’s financial institutions—especially the charity organisation-cum-banking system called the Kard al Hassan (“generous loan”), which has branches all around Lebanon’s cities. This organisation—subsidised by Hezbollah’s construction companies, drug-dealing operations, and charitable Muslim donors—financed the terrorist organisation’s kindergarten and school systems and medical clinics.

Even setting the Israeli–Iranian face-off aside, it is unclear where this war is heading and how it might end. The Israel–Hezbollah clash in the north appears to be developing into an open-ended war of attrition. Hezbollah rockets the Galilee and points south daily while the IAF pulverises additional Hezbollah positions and Shi’ite villages, but neither side can destroy the other or bring it to its knees. And in the south, while the IDF controls most of the Gaza Strip above ground, Hamas fighters continue to dominate the tunnel network—and the Israeli public is increasingly unwilling to suffer daily casualties in continuous firefights as IDF special forces raid tunnel after tunnel. As I write, an IDF division is busy reconquering the Jabalya neighbourhood in the northern Gaza Strip—an area already twice “cleansed” of Hamas fighters in IDF operations —and it is possible that the IDF intends to drive the remaining 200–300,000 Arabs who still live in the ruins of the northern Strip cities southward. Extremist right-wingers in Israel have begun advocating Israeli settlement of the northern Gaza Strip, an area settled by Israelis in the 1990s from which Israel withdrew in 2005, uprooting all its settlements as it left. Ending both mini-wars will require resolute international intervention and a political deal: in Lebanon this will mean IDF withdrawal to the international frontier and Hezbollah withdrawal to north of the Litani River, and the installation of an international force with teeth between the Litani and the border, together with the at least partial disarmament of Hezbollah; and in the south, this will involve IDF withdrawal from all or most of the Gaza Strip, the repatriation of the hostages and Israeli corpses, and an internationally-guaranteed agreement, with teeth, that there will be a non-Hamas Arab government over the Strip.

Both Israel and the Muslim world are now awaiting Iran’s response to the Israeli strike against Iran. In the weeks before the attack, Iran’s leaders promised, through every possible channel, that Iran would respond “mightily” to an Israeli assault. Now, the ayatollahs must decide whether to grin and bear it—or to strike back, which, as Israel’s leaders have already warned, will provoke an Israeli counterstrike. Such a counterstrike, probably delivered after 5 November, will be directed against Iran’s civilian infrastructure and oil installations, and possibly also against its nuclear installations.

So how should the fanatics at the helm in Tehran act? My advice would be: don’t retaliate against Israel; shut down your nuclear weapons project and stop supplying your proxies with arms. Israel has not exhausted its capabilities. If you reject this advice, Iran will likely end up, after a long spiral of violence, a radioactive wasteland.