Art and Culture

Reading Nietzsche in Amsterdam

Lale Gül’s autobiographical novel about a young Muslim woman living in the Netherlands has led to death threats and ostracism. But it is a work of admirable intelligence and courage.

A review of I Will Live by Lale Gül; 320 pages; Virago (August 2024)

Lale Gül’s autobiographical debut novel Ik ga leven (“I Will Live”) was first published in Dutch in 2021 when the author was just 23. It became an immediate bestseller and was published in English translation last month. The story follows the dramatic unveiling of Gül’s fictional counterpart, Büsra, a twenty-year-old Muslim rebel living in the Netherlands and chafing against religious and cultural authority. She hides “cigarettes and lighters under her headscarf,” works a job selling alcohol, wears bikinis at the beach, and has a secret relationship with the handsome son of a Geert Wilders supporter. Unfortunately, the remarkable success of Gül’s book has been bittersweet—she has also received death threats and was ostracised by her family.

The novel opens in a cramped and unventilated flat in Amsterdam-West, which Büsra shares with her severely disabled, obese, and incontinent aunt, Oma. Despite the cheek-by-jowl conditions, the nauseating smell, and the dilapidated neighbourhood, the flat is Büsra’s “little safe haven” from the ideological short-sightedness of her parents (or “begetters,” as she calls them), and Büsra develops a close camaraderie of dissidence with her aunt through their shared “aversion to all things divine.” Chronic disability and a life of abuse have made Oma resentful of Islam. She was promised to her cousin at birth, married off at the age of twelve, became a mother by thirteen, and was raped and physically assaulted throughout her marriage.

Oma’s husband lost all the family’s money playing dice, strangled her two daughters to death when they moaned, and eventually divorced Oma to marry a girl forty years his junior, luring her away from a Turkish village with his Dutch passport. When Oma complains about “her physical pain and very existence”—which, we’re told, “in Islam is equivalent to expressing grievance against the Creator”— her sister (Büsra’s mother) advises her to pray and recite chapters from the Qur’an. Oma scoffs at this advice, refuses to participate in Ramadan, and gives Büsra the remains of her welfare payments to keep her sacrilege a secret.

Gül’s novel is filled with this kind of harrowing material—female illiteracy, physical abuse, arranged marriages, genital mutilation, honour killings, deformed children produced by inbreeding, and the otherwise routine servility of Muslim women. Nevertheless, Gül has leavened her grim subject with irreverent humour, rhetorical flourishes, self-awareness, and a conversational prose style. She names “the local morality preacher” at her mother’s mosque “Iman Blahdiblah,” has a profane Turkish saying ready for most occasions, and offers provocative explanations of “how the wheels on the Islamic bus—with separate sections for men and women, of course—go round and round.”

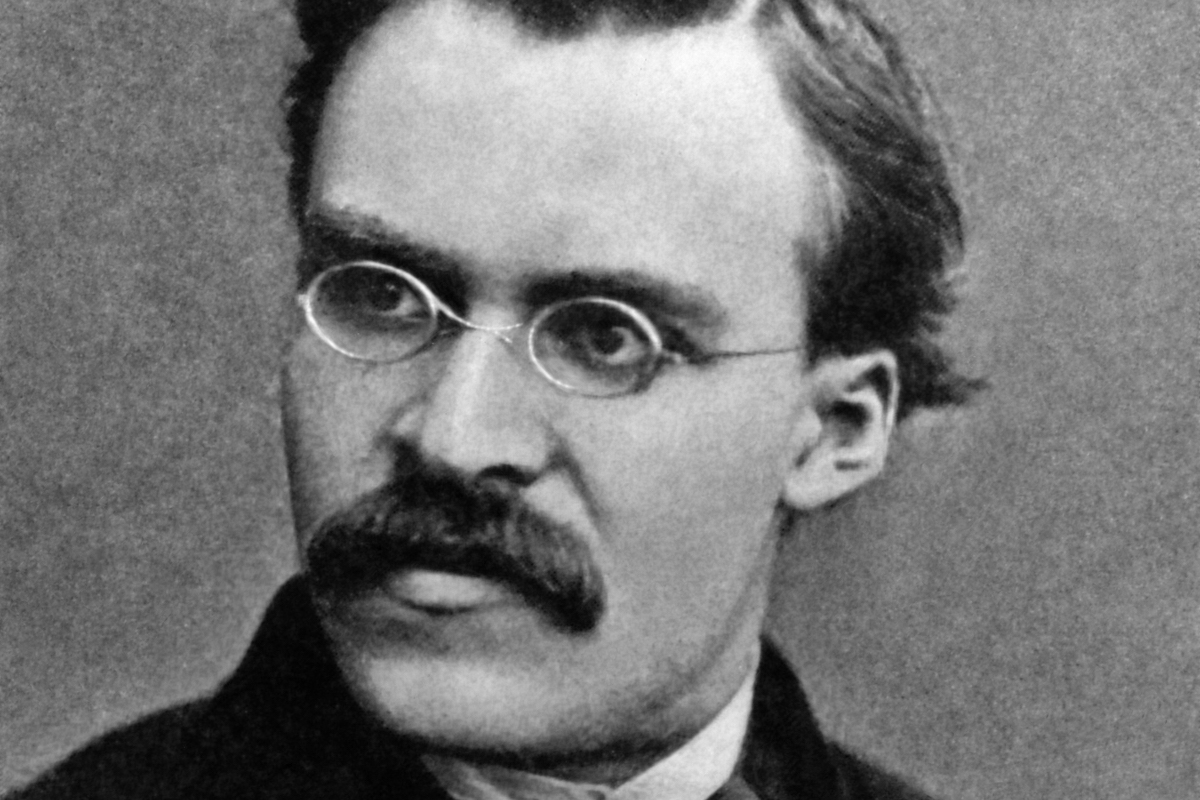

This wit and penchant for philosophical musing allow Gül to resist a crass narrative of victimhood and self-pity, to which it must be tempting to succumb if you are treated like a “house plant” with a “cunt for a man to profit from.” What actually lies beneath her taste for obscene language and anti-theist polemics is a commitment to individualism that she draws from the atheistic freethinker tradition in general and from the writing of Friedrich Nietzsche in particular.

Like the African-American individualist and rebel Zora Neale Hurston (who argued that, in segregated America, “it would be against all nature for all the Negroes to be either at the top, bottom, or in between”), Gül has embraced Nietzsche’s radical anti-egalitarianism (“in this life we all get what we deserve based on our knowledge and ability. … I was forced to surrender to the tyranny of equality”). She nods to his work by creating (like Hurston) her own caustic aphorisms on individuality and collective indoctrination:

Our dear Lord had thought of everything to make the free individual anything but free and certainly not an individual.

Certainty is the firing squad of religion.

Altruism is really just the selfishness of the collective.

A lie derives its status from the number of proclaimers it manages to recruit.

One learns a lot more from searching for truth than from already knowing it.

Hurston and Nietzsche both see the consolation of metaphysical beliefs as necessary for those not strong enough to face the challenges of life by themselves. Compare Hurston’s “People need religion because the great masses fear life and its consequences” with Gül’s “Hope is just a way of outsourcing one’s responsibility.” If Hurston and Nietzsche are renowned for their stylish irreverence, commitment to individuality, and resistance to metaphysical thinking, then Gül, still in her twenties, may yet prove to be a worthy inheritor of this same tradition.

Although searing and often sardonic in her criticism of Islamic teachings and practice, Gül also pays careful attention to the messy knot of religion and culture, and she explores a wide range of theological disputes as she illuminates the migrant underbelly of Amsterdam society. We learn of the differences between the Turkish and Moroccan religious and national identities, temperaments, and sociability. Gül criticises the young people in expensive clothing whose parents live in the poorest part of town, and who listen with juvenile pride to their ethnic kin’s drill rap—a toxic and incoherent mix of “shards of Islamic doctrine” that adds colour to their “aggressive, promiscuous, criminal, nihilistic existence.”

Gül’s Dutch Muslims are often ignorant of larger theological disputes about political Islam and democracy. They experience a “relatively sweet version of Islam” incubated by the institutional stability, economic prosperity, and political freedoms of the West. As such, they are happy to benefit economically from Western advantages—frequently by gaming the welfare system—while remaining ideologically opposed to the customs and mores of Western life. In Gül’s theological criticism, which she restricts to her own understanding of the Qur’anic school, Islam remains “a smoking gun” immune to Enlightenment reforms by virtue of its presentation as the perfect (and therefore final) word of God.

Gül tells stories of liberalised imams and mosques—“like the one in Germany that allowed men and women to pray together or the one in France that opened its doors to homosexuals”—who then receive “bullets and letter bombs in their mailbox.” We hear about the killing of Islam’s critics, about Büsra’s mother’s support for the murder of Samuel Paty, and about hotels set on fire because intellectuals had gathered “to discuss The Satanic Verses.” “If religious fundamentalists are a problem,” Gül muses, “maybe there is something wrong with the fundamentals.”

Nietzschean rejection of metaphysics entails reconnecting with the body. I Will Live includes a graphic sex scene and depicts female lust with admirable frankness. It is the final rebellion for a young Muslim girl whose virginity is supposedly sacred and central to her family’s (particularly the men’s) sense of honour. Interestingly, however, Büsra’s liberal Dutch boyfriend, Lucas, sympathises more with Islamic collectivism than with her own Nietzschean individualism. Unmoored “freedom,” he argues, “leads to loneliness.” The Netherlands have old people “rotting in care homes,” young people with “no sense of purpose,” and “broken families” with “no sense of community.” We’ve “found ourselves in a postmodern landscape of our own making, devoid of tradition, folklore and church.”

The chief merit of Gül’s book is her willingness to stage and articulate both sides of this debate. Drawing her own line of individualism between Islamism and social conservatism, she shows how her family’s Islamic critiques of Western decadence and decline tend to mirror socially conservative (and even populist) concerns about family breakdown, hedonistic culture, and social atomisation. Gül provides no answers to the problems that result from liberalism’s undermining of religious authority, but she does present the counterarguments to her own individualism as pertinent critiques of a spiritually hollow and exhausted West.

Lucas’s claim that “Islam is the last collectivist ideology that has managed to stay afloat” echoes the analysis of Western nihilism presented in French novelist Michel Houellebecq’s Submission, where nothingness precipitates surrender. As Houellebecq sees it, a transpolitical lack of moral and political vision has left the French republic at the mercy of an Islamist takeover. Ultimately, Lucas’s indifference to foundational Western principles is presented as a luxury mindset contingent upon an experience of the Western freedoms he takes for granted. Büsra is reminded of a David Foster Wallace joke: “A young fish is swimming along and encounters an older fish; the older fish asks, ‘How’s the water?’ The younger fish doesn’t know what water is.”

Like Nietzsche, who subordinated group solidarity to his own project of self-becoming, Gül’s resistance to collectivist ideologies is extreme, and it’s worth considering the effect her social environment may have had in shaping her philosophical worldview. When Gül asked her Qur’anic instructor why girls have to cover their heads but not boys, he replied that the question “had been whispered to her by the devil.” At home, an uncle threatened to punch Gül’s teeth out, to which her mother said, “You asked for it with that book.” Through her fictional alter-ego (who, Gül admitted in an interview, is “all me”), we learn of her “intellectual mutilation” and a life never far from an arranged marriage or an honour killing.

Sailing her boat in these headwinds likely required a strong rudder of individualism to forge a path forward. And while I cannot entirely endorse Gül’s neo-Nietzschean project, her guiding philosophy has enabled her to resist victimisation and reclaim a sense of agency. This is both admirable and brave. Gül is a fine thinker, unafraid to break the rules and describe the world as she sees it. I look forward to reading whatever she writes next.