Free Speech

Feminism and Free Speech

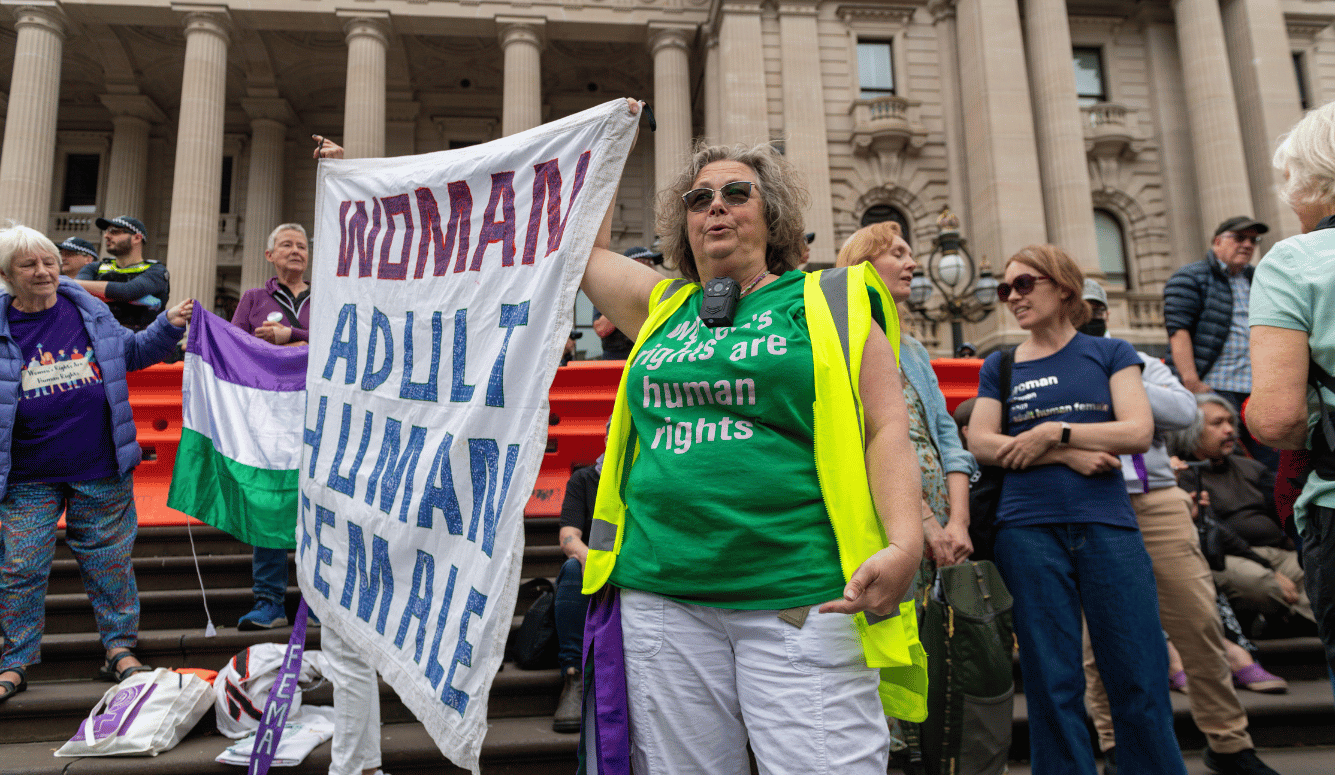

Victoria’s proposed hate speech legislation forces feminists to choose which is more important to them: the restriction of misogynistic speech, or the protection of their own political speech.

Since 2019, plans have been afoot in Victoria, Australia to expand the state’s existing hate speech protections. Currently only race and religion are protected; the idea was to add a number of new protected groups, and to make prosecution easier.

A bill proposed in 2019 made it to a second reading but then lapsed late in 2022. The matter was sent to a parliamentary committee, which recommended in 2021 that legislation go ahead. Draft legislation was expected last year, but has still, as of late 2024, not emerged. However, there is now at least a document providing an overview of the proposed law, on which a public consultation recently closed.

The current proposal is to add both sex and gender identity (as well as sexual orientation, disability, and sex characteristics) to the list of attributes protected by anti-vilification law. It would become a criminal offence to “incite hatred against, serious contempt for, revulsion towards or severe ridicule of, another person or a group of persons on the ground of a protected attribute.” Where the existing law requires incitement to be intentional, the proposed reforms seek to allow it to be merely reckless. The proposed reforms also seek to increase the penalties for this offence, “to reflect the seriousness of the conduct.” The maximum penalty in the existing legislation is six months in prison and/or a fine of $11,855.40 AUD. The maximum penalty for incitement in the proposed reform is three years, a prison time increase of 600 percent. Finally, the proposal seeks to introduce a defence for “conduct engaged in for a genuine political purpose,” which is said to “protect freedom of expression and political communication… [and] allow all Victorians to engage in legitimate political debate.”

At first glance, there might appear to be no problem here. Women gain protection from sex-based vilification, and trans people gain protection from vilification on the basis of gender identity. Two minority groups—minority in the technical, not the numerical sense—gain something, and only misogynists and transphobes lose something. What’s the problem? One problem comes with the defence. The proposal is not that political purpose be a defence for speech, in which case feminist speech would be clearly protected. It is that genuine political purpose be a defence for speech. As we’ve seen play out recently in the Deeming v Pesutto defamation trial, among at least some of Victoria’s politicians, there is a reluctance to accept feminist speech for what it is, which creates a risk that the proposed distinction between “genuine” and non-genuine speech will be used to suppress and silence feminist speech.

Trans-inclusive feminists (who believe that transwomen are women and equally a part of the constituency of feminism) will likely see no tension here, because for them anyone who insists on the reality and political importance of biological sex will be considered a transphobe, a perfectly appropriate subject of anti-vilification restrictions. But anyone who still knows what a woman is will see the problem: women are being offered protection from a form of hateful speech that targets them, but only at the price of having their own speech, which some trans activists consider hateful because it denies trans people’s identity or sense of authentic self, restricted. For gender-critical feminists, and everyone who agrees with them, supporting the anti-vilification legislation means supporting the likely restriction of their own speech, which is a high price to pay even if they welcome the restriction of misogynistic speech.

A familiar rejoinder in free speech debates to the proposal to make hate speech illegal (or prohibited by policy, in the case of universities and companies) is that even the most well-intentioned restrictions tend to redound against those they were intended to protect. That makes sense, because those with the most social power will tend to be the most confident about using the law. In her book Defending Pornography—which despite the title is more an argument against censorship than a defence of pornography—past-President of the American Civil Liberties Union Nadine Strossen details a number of cases in which policy intended to protect minority students from hateful speech on campus was actually used by students from dominant social groups against minorities.

This means that the choice facing Victorians who care about the protection of political speech is not necessarily one in which they give up their right to say things like “trans ‘lesbians’ are straight men” in order to be assured of protection against, for example, misogynistic hate speech on X. They might well find that the first prosecutions under the updated and expanded anti-vilification laws are of feminists, for saying “hateful” things about men (such as “dead men don’t rape”)—including about men who identify as women. For an example of the kind of thing that might be considered hate speech under such legislation, see a recent reaction to trans rights protesters who released crickets and other insects to disrupt an LGB Alliance conference. (Language invoking comparisons to animals and insects is generally considered dehumanising, and dehumanising language is generally considered hateful.)

Trans activists have released thousands of crickets, mealworms, and cockroaches inside the LGB Alliance conference to prevent people from speaking about how trans ideology is harming gays.

— Billboard Chris 🇨🇦🇺🇸 (@BillboardChris) October 11, 2024

The only conversion therapy going on in the West is the effort to maim and sterilize gay… pic.twitter.com/2f55VXEMEV

A plague of insects invading gays and lesbians is the perfect analogy of transgenderism so thanks for that image, fools.

— Venice Allan (@roseveniceallan) October 11, 2024

If censorious legislation and policy tends to redound against those it was meant to protect, we can expect it to redound against feminists. That likelihood only increases when two groups are in the midst of a heated social conflict, as gender-critical feminists and trans activists are, and are both newly protected, as women (sex) and trans people (gender identity) will be. As the Victorian Libertarian Party pointed out in their submission on the consultation, we can similarly expect groups from both sides of the Israel/Gaza conflict to use the legislation against each other (both groups are already protected, but incitement to hatred—decoupled from the threat to person or property required in the existing law—will be substantially easier to prove).

Is this cynical? Perhaps the qualifier “genuine” before “political purpose” should simply be taken at face value, to mean only that speech uttered out of “malice and spite” (to borrow from Joel Feinberg’s discussion of the legal regulation of offensive conduct) will be denied the pretext of being “political.” If I hadn’t been living in Melbourne for the past eight years and watching what kind of feminist speech is granted basic respect (only that which is compatible with all left-wing orthodoxies), and if I hadn’t just sat through the Deeming v Pesutto case and watched politician after politician conflate women’s rights activism with homophobia, transphobia, and even white supremacy, I might read the proposal differently. But given what I know, I think this legislation is going to be bad news for women.