Art and Culture

Culture of Complaint and the New Deal Murals

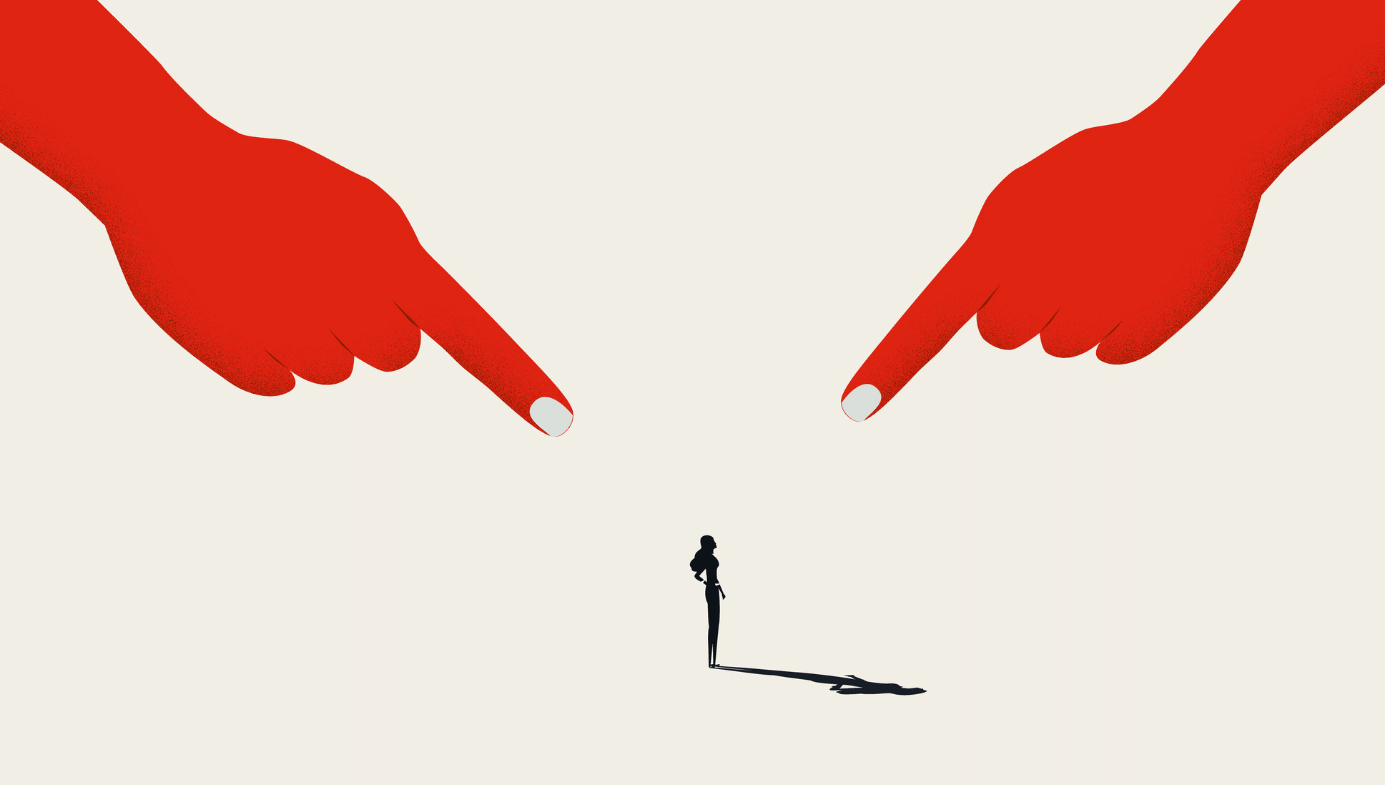

Art in public spaces will always be scrutinised for the propriety of its iconography, and it will remain under attack as long as its guardians are willing to pander to the narcissistic impulses of the activists.

In his most recent book, The War on the West, British conservative polemicist Douglas Murray describes a revealing episode that occurred in the United Kingdom. In late 2020, the Tate Britain gallery announced the permanent closure of its restaurant, which is decorated with a wrap-around mural painted in the late 1920s by Rex Whistler and titled Pursuit of Rare Meats. Two years prior, some members of the public had complained about the mural’s “stereotypical” representation of people of colour. Following an investigation, the Tate’s ethics committee concluded that the imagery was indeed “offensive,” and hungry visitors were told to look elsewhere for their post-gallery lunch.

This investigation was only the latest step in a series of appeasements. In response to a vociferous campaign by an Instagram account called @TheWhitePube, the Tate agreed to contextualise the offending imagery by describing it as “imperialist” and indicative of “attitudes to racial identity prevalent in Britain in the 1920s.” Predictably, this concession was deemed insufficient, and the controversy escalated as the protestors were emboldened to make more strident demands. An online petition was circulated under the urgently authoritarian title “Remove the Racist and Harmful Pursuit of Rare Meats Mural at Tate Britain’s Rex Whistler,” and to prove its commitment to racial justice during the #BlackLivesMatter social-media takeover of 2020, the trustees finally succumbed to activist pressure and closed the restaurant for good. The public will now be spared what a Tate spokesman called “the deeply problematic racist imagery in the Rex Whistler mural.”

Perhaps the most egregious fallout of the trustees’ actions was the damage inflicted on Rex Whistler’s posthumous reputation, which is now tarnished with the stigmas of imperialism and racism. Without any evidence, and despite their mandate as guardians of art, the Tate Britain indulged in anachronistic projection, rooted in the fallacious presentist assumption that modernity is necessarily morally superior to the past. This kind of sanctimonious puritanism entirely disregards the artist’s character or intention. It did not seem to matter that Rex Whistler was a volunteer conscript who died on his first day of action in Normandy, that there is no evidence of racism or malice on his part, nor that the allegedly racist imagery was a minuscule part of the mural as a whole. He and his painting were attacked regardless, due to fears about the imputed impact the worst possible interpretation of his work might conceivably have on the most sensitive and offence-prone observer in London. To those who take their instruction on race relations from Robin DiAngelo, white guilt is axiomatically assumed, and justice can only be restored by suppressing “problematic” art and defaming its creator.

I have some first-hand experience of controversies like these. I was recently asked to write an “artwork study” report for the US General Services Administration (GSA) about Edward Biberman’s 1938 painting Los Angeles—Prehistoric and Spanish Colonial, which is located in a federal building in downtown Los Angeles. One of the many New Deal murals in the GSA’s collection, it depicts a panoramic survey of Los Angeles from the Paleolithic era to the present, populated by several figures: Don Felipe de Neve, the fourth governor of California and founder of the pueblo of Los Angeles; a Franciscan priest; two soldiers firing their guns; and a Native American who, unlike the other figures, is naked.

I was told that the current tenants of the building in which the mural is displayed had expressed “concern” about its representation of the Native American. The GSA’s policy is not to remove or cover up “problematic” murals (unless it interferes with the function of the government). Instead, the agency tries to resolve complaints by providing detailed scholarly studies about the artwork of the kind I was asked to write. Unlike the trustees of Tate Britain, the administrators of the GSA's Fine arts section take seriously their role of protecting the art in their care. They continue the proud history of the WPA (Works Progress Administration) and the Treasury Section of Fine Arts, both of which were inspired by a sincere concern for the public good. During the Great Depression, the government used its art programs to ameliorate economic dislocation and hardship. The idea was to lift the country’s spirit as compensation for its people’s material deprivation.

The original Public Works of Art program was inspired by an earlier initiative organised by the Mexican government in 1922. The Mexican program was cited as a success worthy of emulation by the American artist George Biddle, who praised it in a 1933 letter to President Roosevelt. Biddle argued that the Mexican murals exemplified “the greatest national school of mural painting since the Italian Renaissance,” and that America should follow suit, thereby enabling “a vital national expression.” Under the direction of Edward Bruce in 1934, it was hoped that American government-supported art programs would “add prestige and enthusiasm for the New Deal by securing the best quality art to embellish public buildings; stimulating the development of art; employing local talent where possible; securing the cooperation of those in the art world to select artists for the work to be done; and encouraging competitions whenever possible.”

To ensure the highest quality of commissioned works, the Section of Fine Arts was meticulously planned, and adhered to careful selection criteria with limited subject matter and themes. Along with a system of open and anonymous competition, this guaranteed that the works were chosen for their artistic value. And while artists were free to choose how they painted, the most popular aesthetic was “Traditional American Realism.” The Public Works of Art Exhibition, held in 1934 at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington DC, displayed a cross-section of the work completed under the auspices of the program. President Roosevelt praised the show for “depicting American life in an American way,” and one newspaper reviewer found the murals to be “the most exciting part of the exhibition and a definite brief for a new social order based on the ideals of a true American democracy.” The New Deal murals were as socialist as could be—art for the people, by the people.

One of the two main contingents of artists who participated in the New Deal programs were the so-called social realists, whose ideological leanings were leftist or even communist. This sometimes resulted in (justifiable) accusations of hidden communist iconography. One of the best-known incidents of political conflict over the murals involved the 1934 Coit Tower project in San Francisco, where one of the 25 artists, Clifford Wight, added a hammer and sickle and the slogan “Workers of the World, Unite!” after the original composition had already been approved. Following a brusque correspondence, the Central Office of the Treasury Fine Arts Program compelled Wight to remove the unapproved additions, thereby ensuring that further ideological statements would not be permitted. Nevertheless, the leftist credentials of New Deal art are surely above reproach, so long as one accepts the affirmation of the American spirit as a beneficent and unifying project. But since this concept is entirely at odds with the anti-Western goals of today’s social-justice activists, the murals are subject to complaints anyway.

Naturally, white artists are inherently suspect as avatars of colonialism and racism, irrespective of their personal politics. Although Murray makes a compelling case for Whistler’s patriotism and personal decency, in the absence of a proper anti-racist DEI statement, the artist’s race and nationality both make him vulnerable to posthumous cancellation. Edward Biberman fares a little better in the diversity department, and he lived long enough to leave an unambiguous record of his radical left-wing leanings. As a young child and the only Jew in his class, he recalled being exposed to antisemitism, which fostered his sensitivity to the plight of minorities and the victimised. His older brother Herbert, a film director, was one of the Hollywood Ten, and went to jail for refusing to answer congressional inquiries about his political affiliations.

A good third of Biberman’s paintings and graphic work can be categorised as either social realist (depicting working-class subjects with dignity while acknowledging their exploitation) or anti-imperialist, and he painted civil-rights leaders including Martin Luther King, Lena Horne, and Paul Robson. All of which makes it easier to defend Biberman’s representation of the Native American. This generic figure is clearly not intended to disparage; it simply shows a very common reliance on “types.” Biberman’s 1953 monograph The Best Untold contains page after page of such “types”—variously presented in states of terror, violence, idleness, racism, poverty, hunger, war, greed, politics, grief, beauty, art, and peace—but its author clearly identified himself as an internationalist, anti-imperialist, and anti-colonialist.

Such a defence, based on the artist’s personal ideology, was used in a 2021 court case related to another New Deal mural, Life of Washington (1936) by Victor Arnautoff. Located in a San Francisco high school, the mural came under attack because it allegedly contained imagery demeaning to both African Americans and Native Americans. Some parents complained that the mural was exposing students to racist material, and they demanded that it be painted over or removed. The case went to San Francisco’s superior court, where the judge ruled that the mural could not be removed because the school board had not conducted an environmental review, as required by California law. But she also pointed out that since the painter was a communist, his depiction of America’s first president as a slave owner was obviously not an endorsement of slavery but a critique. Unlike the less fortunate Whistler, Arnautoff was rehabilitated because his known ideological affiliation qualified him for a presumption of innocence.

But this is not how the evaluation of art works on social-media platforms, where guilt is assumed because the only thing that matters is the impact that “offensive” or “problematic” art in public places has on the viewers. Art in public spaces will always be scrutinised for the propriety of its iconography, and it will remain under attack for as long as its guardians are willing to pander to the narcissistic impulses of activists who frame everyone and everything within a reductive oppressor/oppressed binary. The New Deal murals have an advantage here. First, because the aims of the government programs were demonstrably socialist in nature, if not in content. Second, because many of the artists hired to paint the murals were leftists, and even card-carrying communists. As a result, the kind of accusations eagerly dispensed by activists like @TheWhitePube will not stick. Unfortunately, that will not stop today’s self-identifying leftists from trying to cancel the work of historical leftists, because of their poorly concealed resentment of “the American life in an American way” that the New Deal murals celebrate.