The October issue of Commentary features a long article by Abe Greenwald titled “Why Won’t We Let Ukraine Win?” Meanwhile, in the Free Press, Eli Lake has an essay titled, “Let Israel Win the War Iran Started.” Both pieces do an excellent job of describing the absurdity of Western foreign policy in these two conflicts.

First Greenwald:

Time and time again, the Biden administration has refused Ukrainian requests for arms and equipment for fear of “escalation”—only to grant a portion of them after Putin has escalated all on his own.

The pattern is long established. One month into the war, Biden refused to allow Polish-made fighter jets to go to Ukraine. For nine months, he denied Zelensky the Patriot air-defense system his military needed before finally reversing course. The U.S. first ruled out sending Multiple Rocket Launch Systems (MLRS) to Ukraine and then allowed them, with the provision that they not be used to fire into Russia. Also months into the war, the U.S. gave Ukraine High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems (HIMARS), but only after secretly altering them to preclude their firing long-range missiles. The Biden administration didn’t send Ukraine much-needed Abrams tanks until 2023. And while Ukraine had been asking for long-range Army Tactical Missile Systems (ATACMS) since the start of the war, Biden balked until this April, when we supplied the missiles on the condition that they not be used for “long-range strikes inside of Russia.”

[…]

So the U.S. has been too slow in arming its ally, too restrictive in setting conditions on the use of weapons, and generally too fearful of Vladimir Putin’s threats. The result is that Ukraine, for all its unfathomable courage and boundless ingenuity, has been permitted to fight, but not win, the war.

And Lake:

Biden arms the Jewish state and professes his support for Israel’s right to defend itself, but there is always a “but.” Israel has a right to self-defense, but it must do more to protect the Palestinian civilians Hamas uses as human shields. Israel has a right to self-defense, but it should not escalate its war against Hezbollah—even as the terror group fires rockets and missiles over Lebanon’s southern border. Israel has a right to self-defense, but it must participate in ceasefire talks that Hamas has boycotted. Israel has a right to self-defense, but there is no way it can enter its enemy’s last stronghold in Gaza without unacceptable casualties. Put another way, Israel has a right to fight its enemies to a tie.

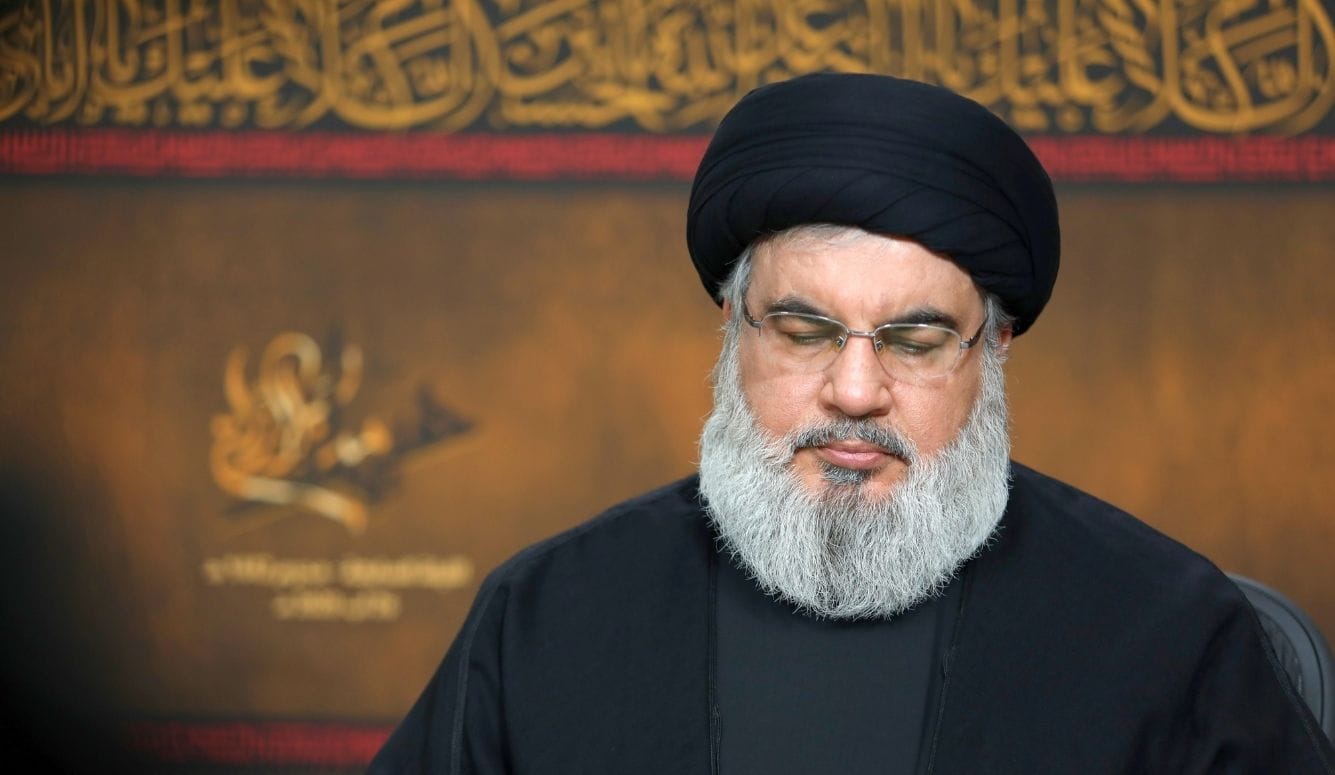

As both authors point out, this novel approach to war, in which one side is afraid of winning in case it further angers its enemies, has led the Ukrainians and the Israelis to hide their plans from their own allies. Ukraine didn’t inform its Western partners about its August incursion into Russia’s Kursk oblast ahead of time, because it knew that those partners would try to prevent it. Similarly, Israel first ordered a strike that might have killed Hassan Nasrallah, the late leader of Lebanese Hezbollah, in the days after 7 October, but the attack was called off after US officials objected. The Israelis decided not to make that mistake again before they assassinated Nasrallah in September, and seem to have shared almost nothing with the US about their plans in Lebanon.

Why are Western leaders so afraid of giving their allies the support they need to win the wars that have been launched against them? In the Ukrainian case, Putin has threatened to use nuclear weapons, but there are strong grounds for supposing that threats like these are a bluff and that Putin is unwilling to risk his own personal safety.

During the pandemic, the Russian leader required his own officials to quarantine for two weeks before coming anywhere near him, and he distanced himself at the end of comically long tables during meetings. He also disappeared from Moscow during the Wagner rebellion until the danger had passed. Indeed, the picture of the Russian elite painted by those who have studied them most closely (Catherine Belton in her book Putin’s People) and those who have become their enemies (detailed in Bill Browder’s book Red Notice about the murder of Sergei Magnitsky) is of a cynical group of thieves whose primary concern is their own enrichment.

Even if there were good reasons to believe that Putin might start a nuclear war, that doesn’t explain the desperate US attempts to prevent Israel from retaliating against the Islamic Republic of Iran. After all, the regime in Tehran seems to be run by exactly the kind of people who would start a nuclear war, given their apocalyptic religious beliefs. They don’t yet have a nuclear capability, but they will acquire one soon unless they are prevented from doing so. Nevertheless, US president Joe Biden has made it clear that America will not support Israeli strikes against Iran’s nuclear sites.

Should Israel decide to defy American wishes and attack Iran’s nuclear facilities anyway, it might destabilise the regime and encourage the majority of Iranians to rise against it (as they did in 2009) at its moment of weakness. The collapse of the Islamic Republic would almost certainly cause the unravelling of its regional proxies, which have brought untold misery to Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Yemen and, of course, Gaza. Such a development could transform the region. This is the optimistic argument that Bernard-Henri Lévy has recently made, pointing out that “in Idlib there are great outpourings of joy” at the demise of Hezbollah.

This may be what Western policymakers fear. Not because they wouldn’t like to see peace and prosperity spreading across the Middle East, but because they can no longer imagine such a future in that part of the world. Recent history has inoculated them against lofty idealism, so the status quo—or rather the status quo ante bellum—appears to be the safest available option. They demand a ceasefire because it would be politically disadvantageous to do otherwise, and because they hope for a return to the familiar scenario of 6 October rather than risk a future scenario fraught with uncertainty.

This is the “realist” consensus now prevailing among the leaders of the West’s democracies. However, there is nothing remotely realistic about this approach if the following propositions are true:

- The war to destroy the Jewish state has begun and will not end until either it has succeeded or the Iranian proxies that launched it have been crushed and the regime in Iran has collapsed.

- A ceasefire offers no path to peace, only a suspension—or more correctly, a prolongation—of the conflict. It is irrational for Israel’s allies to support this outcome unless a ceasefire is in Israel’s interest.

Anyone tempted to doubt the first proposition, from which the second follows, need only listen to what Iran’s supreme leader has to say on the subject. In almost every speech he delivers, Ayatollah Khamenei glorifies martyrdom and eagerly foretells the destruction of the Jewish state. “From the very first day of the Islamic Movement,” he reminded his listeners in June, “the magnanimous Imam [Ayatollah Khomeini] emphasised the issue of Palestine.” He continued:

Operation Al-Aqsa Flood dealt a decisive blow to the Zionist regime, it was a blow that cannot be compensated for. It has put the Zionist regime on a path that will end in nothing but their destruction and annihilation. We have spoken about this many times. We have talked about this on numerous occasions since the beginning of the Al-Aqsa Flood Operation.

While there might be some hope that Putin and the Russian leadership can be convinced by circumstances to end their war in Ukraine, no intellectually honest observer would argue that the Iranian regime and its proxies will ever abandon their determination to destroy Israel. As Khamenei’s “many times” and “numerous occasions” imply, one could quote him, as one could quote the leaders of Hamas and Hezbollah, ad nauseam on the subject. A confrontation with the Islamic Republic was therefore always unavoidable at some point.

A common criticism of the British military establishment during the early part of the Second World War was that its elderly generals were “always fighting the last war.” They were drawing lessons from previous conflicts and mistakenly applying them to Hitler’s onslaught on Europe, which was of an entirely different nature.

A variation of this criticism could equally be applied to Western political leaders today. They are so psychologically disturbed by the failure of the 2003 Iraq War, they are now convinced that no conflict except a wholly defensive struggle for survival is ever worth fighting—least of all in the Middle East.

This lesson was summed up in a 2013 essay by British former Conservative leadership candidate Rory Stewart, who served in Iraq:

The question for Britain is what aspect of our culture, our government, and our national psychology, allowed us to get mired in such [a] catastrophe? [...] We need to reform the army, the Foreign Office, our intelligence agency, and the way parliament debates war, to make us more knowledgeable, more prudent, and more willing to speak truth to power. We must expose not only the politicians but also the generals and civil servants who failed to challenge the system, emphasise the disaster, or press hard enough for withdrawal. We must recognise how easily we exaggerate our fears (“terrorism” and “weapons of mass destruction”) and how easily we hypnotise ourselves with theories (“state-building” and “counter-insurgency”). We must acknowledge the limits of our knowledge, power, and legitimacy.

This passage reflects a more general war-weariness among Western political elites and an assumption that Iraq should mark a turning point in their approach to foreign policy. Would an earlier withdrawal have had better consequences for the future of Iraq, as Stewart seems to imply? He doesn’t say because the fate of Iraq is not his concern. His concern is that we learn the lessons that applied to that war: don’t get “mired” in other peoples’ catastrophes; don’t “exaggerate” the threats we face; don’t become intoxicated by idealism; and acknowledge that our presence can’t hope to be seen as legitimate by the peoples of other cultures. These are all reasonable lessons to draw from a terrible and disillusioning conflict, so long as they don’t become an all-consuming habit of thinking about foreign affairs and a rigid doctrine of isolationism.

For evidence that disenchantment has led to retrenchment and appeasement, one only has to consider the catalogue of foreign-policy failures and blunders by the American-led West in recent years. These include the failure to act after US “red-lines” against the use of chemical weapons were violated in Syria; the futile attempts to reset relationships with Russia (post-Crimea) and Iran—even as the former prosecuted a sophisticated information war against the West and the latter chanted unapologetically for its destruction; and the shameful surrender of Afghanistan to the Taliban. Such avoidable errors only emboldened the world’s autocracies and tyrannies. Were it not for the courage of Ukrainians, the sacrifice of their country might have been added to this list—it was not military support, but a flight out of Ukraine that Biden first offered Zelensky in February 2022. This is the legacy of the lessons over-learned in Iraq.

Since Iran’s second direct attack on Israel, the leaders of the free world have been quick to reaffirm their preferred mantra of de-escalation. Once more, the US paid lip service to Israel’s right to defend itself, but not in any meaningful way. Biden says he has spoken with the G7 leaders and they all agree that Israel “has the right to respond, but they should respond proportionally.” The last time Biden said something like this was after Iran’s first attack on Israel in April, when he told Israelis to “take the win” after the missiles and drones Iran sent were almost all intercepted. The Iranian attack, he argued, had been “defeated and ineffective.”

But Iran’s second attack implies a failure of Israeli deterrence. Last time Iran launched a missile attack on Israel, the US convinced its ally to restrict itself to a perfunctory response. Now, the Iranians have struck again after the Israelis targeted the leadership of a belligerent Iranian proxy. In other words, since anything Israel does to defend itself will be interpreted by the Iranian regime as an act of aggression, appeasement is futile.

If the leaders of the Islamic Republic really believe what they say they believe—and they have been saying the same thing for 45 years—it really should have been obvious that they would embark on the project to destroy the Jewish state sooner or later. This is what the Israelis were saying when the US concluded its nuclear deal with Iran in 2015. Unfortunately, nobody wanted to hear it then, and nobody wants to hear it now.

Witness the lonely campaign of Vahid Beheshti, an Iranian dissident who has been camping outside the British Foreign Office for a year and a half trying to convince the government that the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) is a terrorist organisation. As Arthur Koestler, who also arrived in Britain as a refugee from a less peaceful part of the world, and came up against the same attitudes of incomprehension, once wrote:

Nobody likes people who run around the streets yelling “get ready, get ready, the day of wrath is at hand.” Least of all when they yell in a foreign accent and, by their strident denunciations of the aggressive intentions of Berlin or Moscow (as the case may be), increase international tension and suspicion. They are quite obviously fanatics, or hysterics, or persecution maniacs.

The argument that Israel is "dragging" the US into Middle East conflicts and Biden has "lost control" of Netanyahu is a completely inverted assessment both of the drivers of the current conflict and the actual failures of US policy. TLDR it's Iran: and US failure of deterrence 1/

— Niranjan Shankar (@NiranjanShan13) October 6, 2024

What can be said about the approach to Iran can be said equally about the approach to Russia. The Western powers have been treading on eggshells for two and a half years in an attempt to reassure Putin that they have no aggressive intent towards Russia, but Putin remains convinced otherwise. Western support for Ukraine’s war of self-defence is all the evidence he needs. In his latest comments at the UN, Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov weaved Ukraine and the war in the Middle East into a conspiratorial meta-narrative of Western world domination. This paranoid mentality is impervious to a reality in which the actions of Western leaders consistently err on the side of caution.

The US has withheld vital arms from Ukraine for fear that their provision will antagonise and provoke Putin. This policy is actually just evidence that Russia has succeeded in deterring the West, not vice versa. Putin nurses Western fears with the occasional nuclear threat, but even the risk of being dragged into a conventional war with Russia is negligible. As Abe Greenwald points out in his Commentary essay, since Russia has barely advanced on what it gained in the first days of its invasion, it is hardly in a position to go to war with NATO.

Neither Israel nor Ukraine chose their respective wars; they have been condemned to fight them by neighbours who don’t believe in their right to exist. But post-Iraq disillusion among the Western political elite is making these conflicts longer and more destructive than they needed to be. Worse, the West’s reluctance to use force or support a victory it no longer believes is possible means it is no longer able to deter aggression. As a result, the instincts of Western leaders terrified of another Iraqi quagmire have become a burden and a danger to their threatened allies.