To scandalise is a right, to be scandalised is a pleasure,

and those who refuse to be scandalised are moralists.

~Pier Paolo Pasolini

I.

When Steve Albini died of a heart attack earlier this year at the age of 61, the most common word used to describe him in his obituaries was “uncompromising.” He was one of the loudest and fiercest voices of the American punk and independent rock underground of the 1980s and ’90s. Although most famous as the producer of numerous landmark albums, he rejected the title, referring to himself more modestly as an audio engineer. He preferred not to be credited at all. His trademark sound captured musicians’ live energy and would be ubiquitously characterised as “raw” and “unpolished.”

Best known for producing Nirvana’s In Utero, Kurt Cobain’s angry retort to Nevermind’s blockbuster success, Albini rejected industry royalties, telling the band to name a flat fee so long as they refused to make any concessions to their major label. He likely lost over a million dollars. In his purpose-built Electrical Audio recording facility in Chicago, he worked with countless independent bands that could pay his cheap rates ($900/day for in-house recording). Despising rock-star attitudes, he was an accessible figure, engaging anyone who emailed him and frequently posting on his studio’s vibrant internet message board. His third band Shellac’s posthumous album, released ten days after his death, characteristically opted out of the typical promotional machinery, by, for example, refusing to provide critics with advance copies for review (his “no free lunch” policy). His music only returned to Spotify, a corporation he despised, after his death.

Steve Albini. pic.twitter.com/DzYjvJykdx

— Nirvana (@Nirvana) May 9, 2024

All of this made Albini an iconic figure in independent music, and his name became synonymous with integrity and honesty. Even more than the music he made or recorded, his legacy is tied up with his withering attacks on the music industry. His legendary 1993 manifesto, published in the Baffler and titled “The Problem with Music,” laid out in detail how major labels took advantage of musicians at the height of the post-Nevermind feeding frenzy when even the most uncommercial bands like the Melvins, Tad, or the Boredoms were landing major-label contracts. “Some of your friends are probably already this fucked,” he wrote with characteristic bluntness as he described the realities of a band landing a US$250,000 record deal. Breaking down costs and incidentals to be recouped, each band member would only net about US$4,000 (“about 1/3 as much as they would working at a 7-11”) after selling 250,000 copies that profited US$3 million for “music industry scum.”

Still, some of Albini’s harshest scorn was often reserved for bands with whom he had worked or toured, but who had then made the leap to a major label. One of the most important albums he produced was the Pixies’ 1988 debut LP Surfer Rosa, a landmark of college and alternative rock. A few years after its release, as they opened arenas on U2’s Zoo TV tour, he denounced them in a punk fanzine as “blandly entertaining college rock” whose “willingness to be ‘guided’ by their manager, their record company, and their producers is unparalleled.” In sum: “Never have I seen four cows more anxious to be led around by their nose rings.”

This kind of outspokenness gave Albini a reputation for being an asshole. When Chicago was briefly hailed as the “next Seattle” in the 1990s, he wrote a missive raging against a Chicago Reader “year-in-rock recap” that celebrated local success stories Urge Overkill, Smashing Pumpkins, and Liz Phair by denouncing them all as “pandering sluts.” Characteristically, he signed off with the words “fuck you,” a phrase that encapsulated his cavalier attitude. At the time, the worst insult you could hurl at an independent band was “sell out.” Independent bands—from Jawbox to Jawbreaker—that signed to major labels were often targets of backlashes from their fanbase. Nirvana may have briefly been the world’s biggest band, but Kurt Cobain was openly conflicted about his success. He would appear on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine but with a hand-written T-shirt declaring, “Corporate magazines still suck” (a riff on the slogan of legendary independent label SST Records).

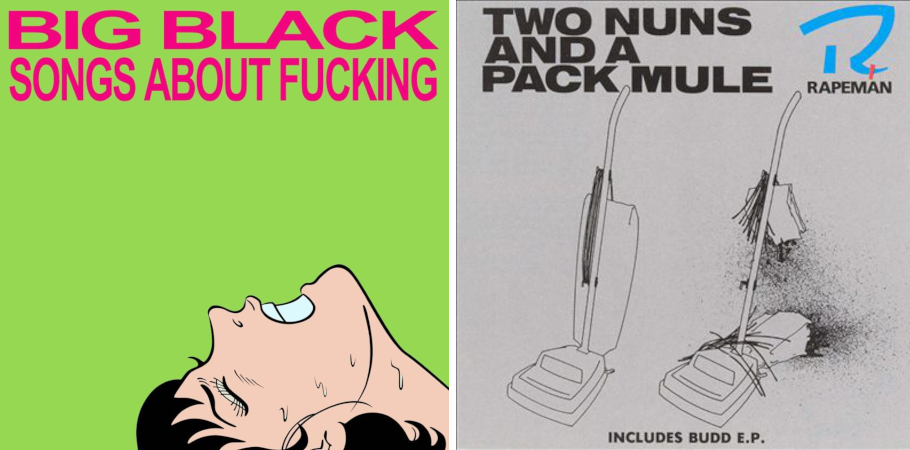

Albini’s rage against the musical establishment and the dominant culture was reflected in music that revelled in violence, aggression, and effrontery. His breakthrough noise-rock band of the 1980s, Big Black, was a post-punk mix of abrasive guitars, industrial drum machines, and snarling vocals that depicted, in their own description, the “darker side of American life.” Songs depicted child rapists, murderers, domestic abusers, fascist dictators, and small-town pyromaniacs, mainly sung from first-person perspectives. Their most popular album was titled Songs About Fucking. Transgression was the point, and Big Black rejected commercial success and broke up in 1987 just as their popularity was peaking.

The same year, Albini inspired protests by naming his subsequent band Rapeman after a Japanese manga about a “superhero” who sexually assaults women. A 1985 side-project featured an even more offensive name and song title. These were deliberate provocations designed to repel any possibility of crossing over to wider audiences, and this put him in stark opposition to many contemporaries from the same independent music scene of the 1980s. In the 1990s, tour-mates like Sonic Youth, the Butthole Surfers, or the Flaming Lips would all balance their more abrasive and experimental tendencies with catchier pop hooks and polished production, which in turn landed them major-label contracts and varying degrees of mainstream success. Sonic Youth signed to Geffen Records in 1991 and Nirvana soon followed. It was a watershed moment. The documentary of their joint tour the same year was fittingly titled 1991: The Year Punk Broke. Decades later, Albini would denounce Sonic Youth’s move to wider commercial viability as “crass,” “offensive,” “distasteful,” “embarrassing,” and an “encroachment into my neck of the woods.”

Albini’s “neck of the woods” was the punk world where offending and provoking mainstream sensibilities was de rigueur, and the ferocity of his opinions was central to his punk ethos. During the 1980s, the avant-garde and underground counterculture revelled in free speech and the right to offend, often in the most tasteless and juvenile ways. Albini’s independent music label Touch and Go was a case in point. One of its earliest releases was a 1983 EP from The Meatmen titled Crippled Children Suck (later re-released in expanded form to include tracks like “Mr Tapeworm,” “I’m Glad I’m not a Girl,” “Tooling for Anus,” and a tribute to John Lennon’s murderer called “One Down Three to Go.”)

The Meatmen were deliberately repulsive, but offensiveness was an art of one-upmanship. In the early days of punk, US bands like the Stooges and the Dead Boys dabbled in swastikas and fascist imagery. UK bands like the Sex Pistols and Siouxsie and the Banshees followed suit. Joy Division, one of the UK’s most influential post-punk bands, were named after the sexual slavery of Jewish women in Nazi concentration camps, and the sleeve of their first EP was illustrated with a drawing of Hitler Youth. Following the suicide of their frontman, Ian Curtis, the surviving members rechristened themselves New Order, a choice retaining clear Nazi connotations.

All of this ran parallel to the shock value found in John Waters’s 1970s films (his 1972 feature Pink Flamingos was famously described by Variety as “one of the most vile, stupid, and repulsive films ever made,” and featured a character wearing Nazi paraphernalia named Patty Hitler) and the “Cinema of Transgression” of Richard Kern and Nick Zedd that emerged from the same scuzzy Lower East Side art scene that birthed Sonic Youth. Even as an indie-rock obsessed teenager in the early 1990s when Albini was at the height of his cultural influence, I did not care for the puerile macho posturing of his music. My own tastes gravitated to the catchier, wry, and more academically effete meanderings of Pavement, a popular indie rock band that Albini dismissed.

Albini’s art was premised on an absolutist commitment to freedom of expression, which he believed formed the basis of the experimental and avant-garde. “Nothing was off limits,” he declared decades later. The most notorious examples of this imperative were two fanzine articles he wrote during the 1980s boasting of the “voyeuristic charge” he derived from looking at child pornography.

The first of these was a 1985 article defending a homemade true-crime magazine named Pure, produced and distributed by his friend Peter Sotos, a fellow Chicago native, musician, and transgressive author. Inspired by the writing of the Marquis de Sade, Pure featured graphic accounts of sexual cruelty and serial murder, and the first issue included a description of child abuse as “a sublime pleasure.” The cover of the second (and final) issue led to Sotos being arrested for possession of child pornography, for which he received a suspended sentence in exchange for a guilty plea.

The second article appeared in 1988 and detailed Albini’s encounter with child pornography that he claimed to have bought in Hamburg while touring Europe with Big Black. “Jaded as I am,” he wrote, “I can’t help but flip seeing a girl and guy of twelve or thirteen, tops, ramming Martel bottles up each other’s asses. These are not the Dutch equivalent of abused trailer-park kids, either. They look to be in excellent health and seem to be honestly enjoying this. Makes all the conventional arguments against this kind of thing seem really silly.”

Neither Sotos nor Albini was ever charged with actually abusing or photographing children themselves, but they certainly enjoyed talking about it as flippantly and tastelessly as possible to épater les bourgeois. Nobody else, Albini implied, was fearless enough to be this phlegmatic and frank about the very darkest corners of human behaviour and sexuality, his own included. And if ordinary people found what he had to say appalling and disgraceful, then so much the better.

As for the frequently disturbing content of his own music, Albini simply expected his audience to understand that he was neither expressing his own views nor endorsing the perspectives of the characters in his songs. While his song “Il Duce” with its chorus “I am Benito” may have been written from the perspective of Italy’s fascist dictator (or, more likely, as a metaphor), only the crudest literalist would interpret it as an endorsement of fascism. But a number of prominent critics missed the point, including The Village Voice’s Chuck Eddy who linked Big Black with actual “white-trash pride” neo-Nazi punk groups like Skrewdriver.

This all came at a time when cultural censorship was enjoying a political moment. Senator Jesse Helms and the religious Right waged war against the National Endowment of the Arts over its funding of artworks like Andres Serrano’s 1987 “Piss Christ” photograph of a crucifix submerged in a glass of the artist’s urine. Tipper Gore, then the wife of then-senator and future vice-president Al Gore, founded the Parents Music Resource Center, which promoted moral panics over songs as tame as Sheena Easton’s “Sugar Walls” (offending lyric: “Come spend the night inside my sugar walls”). Rap and heavy metal were the PMRRC’s primary targets, which led to the comical spectacle of Twisted Sister’s Dee Snider testifying in a Senate hearing and sounding far more reasonable than Al Gore and his colleagues.

Although ubiquitous Parental Advisory labels attempted to keep supposedly dangerous music out of the hands of impressionable young people, as a thirteen-year-old in 1988, I could still purchase a cassette tape of NWA’s Straight Outta Compton from a suburban Sam Goody without any problem. As Bret Easton Ellis has recently argued, Generation X “wanted to be offended.”

II.

In the last years of his life, Albini began to distance himself from—and even express contrition for—some of the more provocative pronouncements he made early in his career. Some of this can be attributed to the diminished stridency that comes with greater maturity and experience. For instance, discussing the Pixies’ Surfer Rosa album on the Life of the Record podcast in 2023, he said:

Every now and again, I have cause to hear the Pixies album that I worked on in context somewhere. Like I’m in a bar and a song will come on, or I’m watching a movie and a song will come on. And I think it’s a better record than I thought it was at the time. At the time, I had all of these, like, conflicting intellectual perspectives on it, and I couldn’t just listen to it for its effect. And now, when I hear it as a finished record, I think it sounds very good. And the band sounds very good. And I don’t find a lot to criticise. When they first started to become more well-known in the US, a lot of people in underground circles were suspicious of them. They were a bit naive about the workings of the music industry, I guess is the way you’d put it, and they seemed very credulous. And I talked about this a little bit with respect to me influencing the album by making suggestions and them acceding to all of my suggestions. I wrote some rather glib and unflattering things about that in a fanzine in the immediate aftermath of that record, and I’m ashamed of the way I treated them. They didn’t deserve that.

But Albini’s attitude towards his own transgressive ethos also underwent a radical change. In the intervening decades since Albini’s peak influence, a tectonic shift in US culture occurred as subsequent generations became far more sensitive to language as an instrument of oppression and violence, and this left Albini mortifyingly out of step with his peers. Offensiveness, provocation, and transgression of norms are now identified less with the radical Left than with the radical Right, epitomised by the internet trolls of 4chan and the crude political style of Donald Trump and his MAGA movement. More importantly, the Left abandoned freedom of expression as a core value, ostracising dissenters as it grew to resemble its former opponents on the censorious Right of the 1980s. By today’s standards, Albini would be dismissed as racist, misogynist, and homophobic and ripe for cancellation, especially by the urban, educated, artistic, and politically enlightened elite from his side of highly segregated Chicago.

This political and cultural shift may explain why Albini began publicly recanting and apologising for his past transgressions in numerous tweets, podcasts, and interviews. In 2021, he tweeted a six-part thread in which he wrote, “I certainly have some ’splainin to do, and am not shy about any of it. A lot of things I said and did from an ignorant position of comfort and privilege are clearly awful and I regret them.” The thread went viral and prompted numerous interviews in which he expanded upon his comments. He pleaded for forgiveness for his “role in inspiring ‘edgelord’ shit.” With respect to his embrace of trans rights activism, he would later add, “Life is hard on everybody and there’s no excuse for making it harder. I’ve got the easiest job on earth, I’m a straight white dude, fuck me if I can’t make space for everybody else.”

I certainly have some 'splainin to do, and am not shy about any of it. A lot of things I said and did from an ignorant position of comfort and privilege are clearly awful and I regret them. It's nobody's obligation to overlook that, and I do feel an obligation to redeem myself...

— regular steve albini (@electricalWSOP) October 12, 2021

“For myself and many of my peers, we miscalculated,” he confessed. “We thought the major battles over equality and inclusiveness had been won, and society would eventually express that, so we were not harming anything with contrarianism, shock, sarcasm or irony.” It is hard to believe that Albini was unaware of the pervasive racism in Chicago in the 1980s, a city credited with “inventing modern segregation,” or that he thought the battles against homophobia were already won during the peak of AIDS hysteria. Apparently, he only came to see racism, homophobia, and sexism in bleaker terms in the 2020s, not four decades earlier when he was at the apex of his cultural influence and all those things were far worse.

Kurt Cobain denounced homophobia in the early 1990s, wore dresses on stage to antagonise jock audiences, sang “God is gay,” praised feminism, and referred to the future of rock as female at a time when the most popular rock bands like Guns N’ Roses and Skid Row were openly homophobic and sexist. Meanwhile, Albini’s final album with Shellac features a song called “Chick New Wave” that, whether the title is sardonic or not, opens with the lyrics, “I’m through with music from dudes.” That song may have been pertinent three decades earlier, during the first wave of the Riot Grrrl movement, when women were routinely groped or worse in the mosh pits at punk shows. In 2024, it sounds dated and trite.

Was Albini’s repentance sincere? From someone known for his blunt honesty, these admissions came late and seemed to be a part of the bandwagon-jumping rhetoric that followed the #MeToo and George Floyd frenzies that swept the culture during Donald Trump’s chaotic presidency, especially given the platitudes about “acknowledging privilege” and “making space for others.” Those terms and statements like, “I’m responsible for accepting my role in the patriarchy, and in white supremacy, and in the subjugation and abuse of minorities of all kinds” feel like the generic self-flagellation that might result from forced attendance at a corporate-mandated DEI workshop. His statements sounded less like the product of raw honesty than the recitation of a standardised culture script at a moment when he might otherwise have faced expulsion from polite society for his past transgressions.

In fact, Albini made comments well into middle age that defended his earlier offensive remarks and behaviour. In Michael Azerrad’s 2001 book, Our Band Could Be Your Life: Scenes from the American Indie Underground 1981–1991, Albini roundly justified himself. “A lot of people, they’re very careful not to say things that might offend certain people or do anything that might be misinterpreted. But what they don’t realize is that the point of all this is to change the way you live your life, not the way you speak.” Public civility and conformity to social norms often masks a lurking coarseness or violence, so he maintained that people should be judged by their actions not their words. “I have less respect for the man who bullies his girlfriend and calls her ‘Ms’ than a guy who treats women reasonably and respectfully and calls them ‘Yo! Bitch.’” This position was, needless to say, sharply at odds with the “sensitivity culture” that has emerged in recent years.

By all accounts, Albini lived according to his own credo. His personal conduct was quite unlike his public image. Upon his death, a #thankyoustevealbini hashtag appeared on Twitter, where former musicians and fans spoke affectionately about their personal encounters with him. Frequent female collaborators referred to him as a “gentleman” while numerous others referred to him as a genuinely “nice guy.” Although his music scene was, like almost all cultural spaces of the time, male-dominated, he was broadly “inclusive” by nature. He recorded and mixed two groundbreaking albums by female musicians: the Breeders’ Pod in 1990 and P.J. Harvey’s Rid of Me in 1993. He also recorded Pansy Division, one of the first openly gay rock bands, who pioneered a punk subgenre known as “queercore.”

Although many observers attributed Albini’s transformation to a “mellowing out” or “softening” with age, his vitriolic derision of those he held in disdain never diminished. The targets simply changed. He continued to hate the ’70s yacht-rock jazz-fusion stylings of Steely Dan (an easy musical target), but his political invective was now almost exclusively directed at the safest and most obvious liberal targets—Trump and Trump supporters, Republicans in general, Joe Rogan, and any cultural figure denouncing wokeness or cancel culture. (“However you define ‘woke,’” he tweeted in 2023, “anti-woke means being a cunt who wants to indulge bigots.”)

In 2011, Albini caused a stir when he posted in his website’s forum about an encounter with hip-hop artists Odd Future. At the time, Odd Future were young rising stars influenced by a subgenre of rap known as “horrorcore” that traded in confrontational and transgressive lyrics about murder, cannibalism, necrophilia, and sexual violence, all peppered with homophobic and sexist slurs. Employing language that, a decade later, he would ruefully describe as “inexpertly rendered,” Albini recalled:

My band shared an airport shuttle with [Odd Future] in Barcelona. They piled onto the shuttle late, after finally getting corralled by their minder, who was nursing a head wound with an ice bag wrapped in a towel. They piled in, niggering everything in sight, motherfucking the driver, boasting into the air unbidden about getting their dicks sucked and calling everyone in the area a faggot. Then one of them lit a joint (or a pipe, I didn’t look) and told the driver to shut the fuck up nigger and smoked it anyway. A female passenger tried to engage one of them in conversation, but he just stared at her with a dead-to-me stare while his seatmate flipped double birds in her face.

The whole trip they complained about not being at a McDonalds and repeatedly shouted for the motherfucker to pull over so they could get some fucking McDonalds nigger. Interspersed with the McDonalds requests were shouted boasts about how often they masturbated and fucked bitches nigger and got paid like a motherfucker fifty grand like a motherfucker. They continued complaining that the trip was taking too long and insisted they be fed immediately all the way to the airport, where their minder presumably fed them.

I am quite happy none of them engaged me directly, because at least one of us would have regretted it.

Albini was not a fan of hip hop but the similarities between Odd Future and Big Black were hard to miss, and Odd Future defended their music in the same terms that Steve Albini had used to defend his own provocations years earlier.

As Odd Future’s popularity grew, a brief moral panic ensued. They were kicked off a festival programme by organisers scandalised by their lyrics, and the band’s leader—Tyler, the Creator—was banned from entering New Zealand, Australia, and the UK for several years because he allegedly posed “a threat or risk to public order or the public interest.” They eventually softened as they assimilated into the musical mainstream, and turned out to be one of the more influential groups of the last decade. Interestingly, many members associated with the collective came out as gay, including Frank Ocean, whose announcement in 2012 is credited with having “changed the landscape.”

III.

Over the past decade, the independent music scene in the US has likewise moderated to reflect newfound sensitivities on the Left. Out went the deliberately outrageous band names designed to scandalise the moral majority, and in came new speech codes intended to defend public decency. Even innocuous band names became targets of scorn and rechristening campaigns. Indie rock band British Sea Power dropped the word “British” from their name because they did not want anyone to think they were glorifying British imperialism (even though the name’s intention was tongue-in-cheek). Girl Band, a male Irish noise-rock group, had to apologise for their “misgendered” name in 2021, a choice they said came “from a place of naivety and ignorance.” The white and male UK band Slaves were named in reference to job drudgery, but they had to rechristen themselves Soft Play in 2022 after years of outcry.

Canadian post-punkers Viet Cong—formed after their previous all-male band Women disbanded a few years before that name would have drawn protests—changed their name to Preoccupations after petitions, outrage, and concert cancellations. It did not matter that the Viet Cong might otherwise be considered decolonial heroes by those pushing the band’s cancellation—they were white men so their name was racist. Naturally, they professed ignorance but their careers never really recovered from the controversy. Decades earlier, Gang of Four—one of Preoccupations’ key influences along with Joy Division—could be named after China’s infamous Maoist faction without eliciting complaints (except perhaps from those who objected to their anti-consumerist lyrics).

While Albini was railing against those railing against “cancel culture,” many younger artists would privately admit that fear of being cancelled for an unintended misstep has a stifling effect on creativity. When a mainstream success story like Donald Glover links the fear of being cancelled to boring cultural products, it ought to indicate that censoriousness has become a problem. Artists are now unwilling to take risks and afraid of speaking their minds on controversial topics because they see what happens to those who do.

A case in point is Ariel Pink, a genuine musical oddball and arguably the most important and influential indie musician of the past two decades. Like Albini, Pink had a prior history of opinionated and transgressive comments that caused many music critics to categorise him as a troll or an edgelord, but he became a “music industry untouchable” in 2021 after he attended Trump’s 6 January rally. His label dropped him, many indie venues won’t host him, his fans and collaborators abandoned him, and music sites that described him as a genius a decade earlier will no longer cover him. The idea that a person can appreciate the music of someone with strange beliefs or objectionable political views is anathema to the current moment, even though the history of popular music is littered with idiosyncratic individuals. Around the time his 1976 album Station to Station was released, David Bowie extolled fascism and called Hitler “one of the first rock stars.” We live in much less forgiving times today.

Albini followed many other liberals by defecting from Musk’s Twitter for the friendlier climes of Bluesky. His final post there was a denunciation of Trump. Once the fearless iconoclast, by the time he died, his social-media posts had become indistinguishable from all the other self-righteous and angry liberal/progressive voices ranting profanely about Trump and his stupid supporters to the nodding agreement of their like-minded followers. “When you realise that the dumbest person in the argument is on your side, that means you’re on the wrong side,” he told the Guardian in 2023, a remark that neatly encapsulated his new credo.

More to the point, his positions became indistinguishable from those of the safe, corporate-media establishment that his most important work in the 1980s and 1990s aimed to offend, subvert, and contest. Unsurprisingly, his contrition was greeted with reverential awe by that same cultural elite. As the Atlantic put it in the headline of their obituary, “Steve Albini Was Proof You Can Change.” The tribute from influential music website Pitchfork went even further, proclaiming, “Steve Albini Did the Work,” a reference to the antiracist imperative as much as to his famous professional ethic. Like the Atlantic, the Pitchfork obituarist found his subject’s risk- and consequence-free repentance to be “the most astonishing and inspiring” thing he ever did, histrionically likening him to a “punk-rock Tony Robbins” of transformative change and personal development.

The story of Pitchfork’s rise and fall is itself emblematic of wider changes taking place within the independent music world. Started by a record-store clerk in suburban Minneapolis in 1996, it emerged from indie rock’s ’zine culture. By the first decade of the 21st century, Pitchfork was one of America’s most popular and influential music websites, known for unconventional reviews, unruly personal styles, and polemical opinions that earned them the disdain of established critics. They were tastemakers and a glowing Pitchfork review launched numerous careers. They franchised into festivals. However, by the time the site was waxing ecstatic about Albini’s great transformation, it had become a shadow of its former self.

Pitchfork lost its independence when it was acquired by media giant Condé Nast in 2015. In 2010, Albini was interviewed by fellow Condé Nast publication GQ magazine and concluded by telling them, “I hope GQ as a magazine fails.” As it happened, Condé Nast ended up folding Pitchfork into GQ at the beginning of 2024 and laying off most of its staff. Vice magazine followed a parallel trajectory from provocative irreverence in 1994 to corporate darlings espousing bland progressive orthodoxies in the 2020s. Vice was franchised into a media empire, and at its peak, it was valued at US$5.7 billion dollars only to slump into failure and bankruptcy in 2024.

But even before the Condé Nast takeover, Pitchfork had long stopped focusing on indie rock and began covering popular music more broadly, even publishing articles attacking the independent scene for being too white, too male, and too straight. Indie rock, it now declared, was a “comparatively conservative genre” and “the province of white, heterosexual males.” Vice went through an even more extreme makeover to atone for its past sins as it accumulated economic value. That Albini, Vice, and Pitchfork would all end up conforming to the same enlightened views about race, gender, sexuality, and politics seems to confirm that nobody preaches with quite the fervency of the new, guilty convert.

Albini had been an outspoken critic of the music industry’s crude economic realities and he held the corporate world in contempt, so the focus on his transformation speaks to the contemporary Left’s sacrifice of economics on the altar of identity politics. How else to explain Pitchfork disparaging a musical genre as “conservative” that was originally defined in economic terms against corporate cultural power. And were Vice’s and Pitchfork’s makeovers not precisely what made them appealing to corporate media? Attacks on “indie rock” in Pitchfork were symptomatic of a wider movement in music criticism known as “poptimism”—the notion that pop music (now coded as black and female and queer) deserved to be treated with the same seriousness as rock music (coded as white and male and straight).

This dichotomy was always disingenuous (as if Sleater-Kinney were not considered one of the best rock bands of the past quarter-century by music critics), but it was also part of the same movement that reclaimed Britney Spears as a feminist icon only to eventually disown her again. Within this dualism, being accused of “rockism” (as Albini, who hated electronic dance music and disliked hip hop, undeniably would be) is akin to being accused of racism. By the second decade of the 21st century, “poptimist” perspectives had taken over almost all of music criticism, from Pitchfork to NPR to the refined pages of the New Yorker.

The result of this cultural moment is best encapsulated by the unrivalled musical and economic dominance of Taylor Swift, an artist who is now critic-proof. Any critical commentary risks incurring the wrath of Swifties. One of the few times Albini discussed Swift was when he joined an online pile-on of a hapless conservative journalist who wrote a silly article dismissing Swift’s popularity as a sign of societal decline. In the song “Kool Thing” from Sonic Youth’s major-label debut Goo in 1990, bassist Kim Gordon asked the song’s eponymous figure (voiced by Public Enemy’s Chuck D but clearly based on LL Cool J): “Are you gonna liberate us girls from male white corporate oppression?” Decades later, liberation from “male white” oppression has become the focus of the identity-obsessed Left. But while demonstrable progress has been made in gender and race relations in the US, “corporate oppression” is worse than ever, especially on the cultural front, despite—or, rather, because of—the advent of Taylor Swift’s brand of girlboss feminism.

From what I know, Taylor Swift is one of the smartest people in music.

— regular steve albini (@electricalWSOP) September 27, 2023

Oh, almost forgot.

Let's hear your record, cocksocket. pic.twitter.com/dvFz4UTh0C

IV.

Since the 1990s, just as cultural sensitivities dramatically shifted, the music industry was also radically transforming. Illegal downloading and then streaming destroyed music sales, notwithstanding a minor niche resurgence in vinyl sales. Bands used to tour to sell albums. In the new reality, releasing albums generates little income but it does help generate interest in tours, which are now the dominant source of musician income. Meanwhile, touring conditions have dramatically worsened. As a recent antitrust suit filed by the US Justice Department attested, LiveNation’s monopoly on touring has resulted in a stranglehold on venues as well as ticket distribution. Even worse, venues now routinely take up to 30 percent of t-shirt and merchandise sales at shows, thereby choking off a last important source of revenue for artists.

In short, the move to free content has been catastrophic for musicians. Surprisingly, however, Albini became a techno-optimist, cheering changes that he believed would solve the “problem with music” he identified back in the 1990s. New technologies, he believed, would allow artists to cut out the middlemen, from corporate distributors and record labels to radio stations and the entire PR machinery he despised. But while Albini remained sanguine about the ways in which the internet allowed for unmediated contact between musicians and their fans, the new digital panhandling required by sites like Patreon did not democratise music so much as devalue it. Once music became free, it was hard to convince people to spend money on it.

The effects of this change have been so bad that many musicians who have been around long enough now see the 1990s, the period Albini targeted, as one of its last golden ages. Profits from cheaply manufactured CDs (artificially inflated by music companies) were so large that the industry was awash with money, and many artists were, at least, able to make a modest living. The online revolution has only empowered big tech companies, who sweep up the profits and use algorithms to decide what music gets your attention. Payouts for even relatively established artists are pathetic, with a million streams on Spotify netting somewhere between US$3,000 and US$4,000. In the CD era, a band may have been able to survive on 30,000 album sales with a reputable independent label. But the new boss turned out to be worse than the old boss with an even greater and more pernicious stranglehold on both the culture and economics of music.

This convergence between Albini and the corporate world occurred at a time when the independent music scene that Albini represented was starting to experience its worst systemic crisis. And if independent music was in a precarious state before COVID-19, the pandemic and its aftermath may have been the death blow. COVID is yet another issue where Albini’s views conformed entirely to the prevailing liberal elite view. He unwaveringly supported lockdowns and restrictions, and he was happy to shun, shame, and moralise at anyone who disagreed. Two years into the pandemic, he was still referring to anyone who raised questions about the efficacy of masks as “assholes” who “have decided not to care.” That same year, he responded to a statement that encouraged vaccination but stopped short of mandating it for young university students by tweeting, “These fucking people, I swear. It’s a death cult.” He even appeared double-masked for a meeting with a Guardian journalist at an outdoor cafe that summer: “In the course of the many hours we spent together over the next week, I saw the lower half of his face maybe half a dozen times—only when he lowered both of his masks to sip his drink.”

Meanwhile, many music venues were destroyed by COVID-19 lockdowns. In Toronto, a city that endured one of the world’s longest lockdowns, 22 music venues were shuttered in 2020. That didn’t stop Albini from lambasting anyone “pretending the pandemic [was] over.” By the time venues were finally able to open at full capacity and without restrictions, the promised post-pandemic boom turned out to be a mirage as inflation wrought havoc on the economic sustainability of those small venues that survived. The cost of touring increased exponentially as hotels, fuel costs, and all the other incidentals of touring gutted the profits. Even established musicians were forced to cancel tours as bands reported losing their last source of income.

Many reputable musicians are now forced to tour solo to turn a profit, unable to afford the costs of a band. In 2023, 16 percent of the UK’s small independent music venues closed. In Toronto, 15 percent of venues permanently closed. Since the pandemic, ticket prices have skyrocketed, as LiveNation consolidated even more power, and limited venues meant even more intense competition, especially after two years of cancellation. Many fans are now priced out of the market or have to save if they want to pay for exorbitant Taylor Swift tickets or to see an Oasis reunion. The situation has only been exacerbated by Ticketmaster’s “dynamic” ticket pricing and other dubious price-gouging practices. Bookers will say that venues are no longer willing to risk staging smaller and more obscure or unestablished acts, preferring cover bands, dance nights, or older bands playing their classic albums from front-to-back on an endless nostalgia trip. The result is a flurry of think-pieces lamenting the demise of the middle-class musician.

It has become common to read that we now live in an age of cultural stagnation. Even the New York Times decries the sorry state of teen subcultures. The experimental and rebellious drive that involves a willingness to transgress norms, offend sensibilities, provoke controversy, and disturb the establishment is curtailed by cultural conformity and fear of offending sensitivities. Meanwhile, tech giants have turned listening to music into a “soulless algorithmic wasteland,” while the physical infrastructure for live music is increasingly imperilled by a corporate monopoly and economic conditions hostile to innovation. Any vibrant new counterculture will have to break through this current stasis and reclaim the spirit of independence and absolute freedom that, for better and worse, drove Steve Albini to produce some of the most exciting music of the 1980s and ’90s.