Politics

Stop Complaining About the Electoral College

It remains the least undesirable system and changing it is impractical.

As the November election approaches, the United States’ electoral system is coming under renewed scrutiny. The US uses an Electoral College system, which counts every person’s vote and then assigns that vote a value based upon the size of their state. States with larger populations get more Electoral College votes. So, for instance, Alabama (population ~5 million) has seven congressional districts and two senators, which gives the state nine Electoral College votes; California (population ~39 million) has 52 congressional districts and two senators, which gives the state 54 Electoral College votes.

There are 538 Electoral College votes up for grabs, so whoever wins 270 or more wins the presidential election. With the exception of Nebraska and Maine, all states allocate their Electoral College votes on a winner-takes-all basis—so if a presidential candidate wins California by a single vote, he or she will nevertheless receive all 54 Electoral College votes. This can lead to lopsided results that do not reflect a candidate’s popular support. In the 2020 election, Joe Biden got 81.3 million popular votes (51.3 percent) to Donald Trump’s 74.2 million (46.8 percent), but he won 306 Electoral College votes to Trump’s 232.

Occasionally, an election result will be split between the popular vote and the Electoral College, as it was in 2000 and 2016, when the Democrats won the popular vote but lost the Electoral College count. At the time of writing, there is a nontrivial chance that this outcome could be repeated in November. In a post published on 17 September, US polling analyst Nate Silver estimates:

There’s now almost a 25 percent chance that Harris wins the popular vote while losing the Electoral College (and only a 0.2 percent chance of the other way around). This gap has continued to grow. And it can make poll-reading really counterintuitive. You’ll see lots of headlines saying that Harris is leading—but our elections aren’t determined by the popular vote.

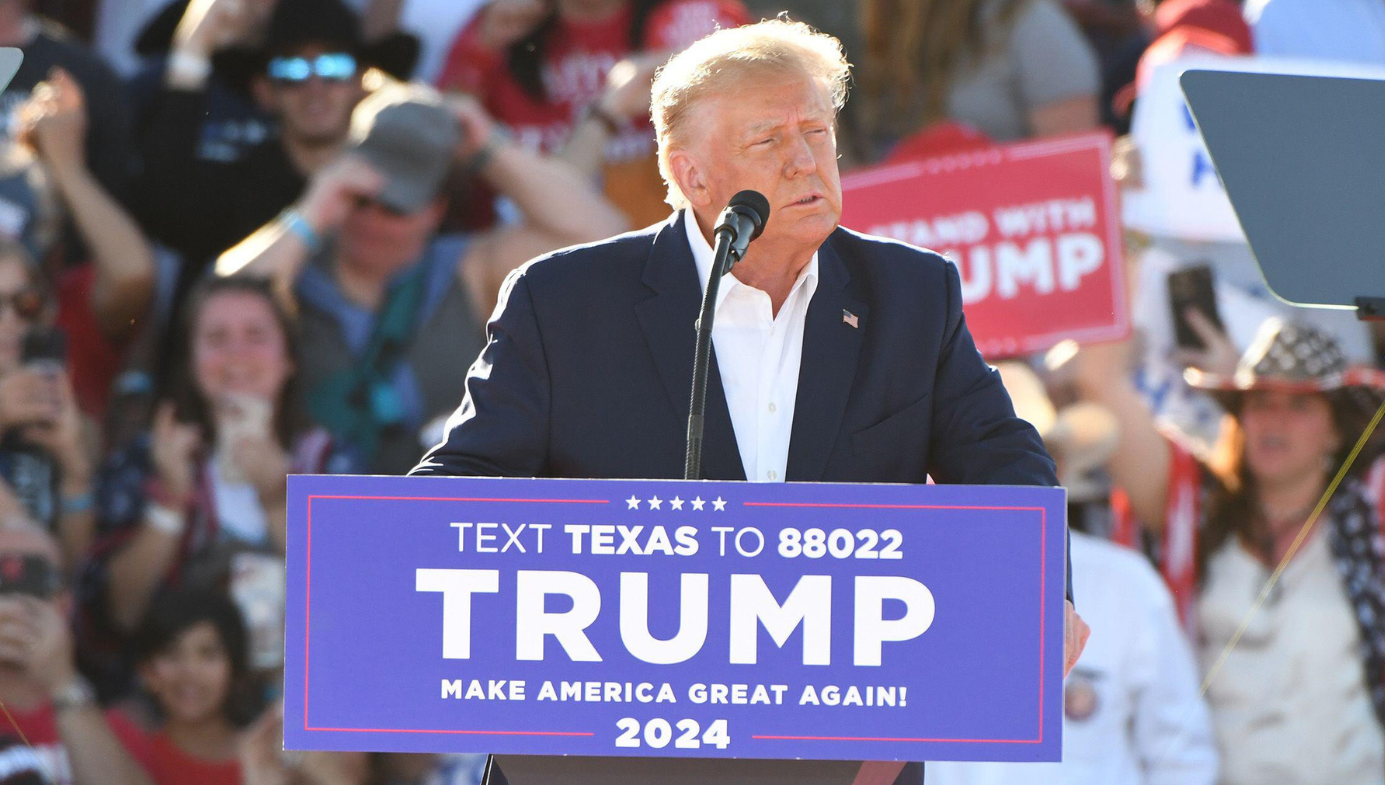

The prospect of a split result returning Donald Trump to the White House is leading more and more political analysts to argue that the Electoral College system is unfair and unrepresentative and that America should adopt a system of popular-vote tabulation to determine the winner instead. As Perry Bacon Jr. argued in the Washington Post on 16 September, “The U.S. presidential election system—with winner-take-all states and the electoral college—warps the political process and even the way people see their own country.”

Maybe it does. But Bacon doesn’t explain why the Electoral College system was introduced in the first place. Nor does he address the obstacles anyone seeking to change it will encounter. I don’t want to get into the pros and cons of the popular vote versus the EC system. I want to explain why discussing such a change is moot, because it is simply not possible in practice.

Compromise is an unavoidable part of any democratic system. When the US Constitution was drafted in 1787, the founders had to decide how the freshly independent and conjoined British colonies would elect the president of the new union. That debate provoked a good deal of disagreement and distrust. Some states wanted their legislatures to vote for the president, while others argued for a popular vote. The compromise solution didn’t make anyone happy but it was deemed acceptable enough to win ratification. As Jonathan Gienapp, a professor of history at Stanford University, explained in 2022:

Why did the Constitution’s authors choose this particular system for electing the president? The most important thing to appreciate is that they chose the Electoral College not because it was the most desirable option, but because it was the least undesirable. The leading alternatives—legislative selection by Congress or a national popular vote—were met with powerful objections. If Congress elected the president, it was feared that the latter would become the puppet of the former, nullifying any hope of executive independence. When it came to a national popular vote, meanwhile, there were worries that, at a time when information moved slowly, especially across such a large nation, voters would be familiar only with the candidates from their home states and thus tend to choose them. There were also grave concerns that the people would be seduced by demagogues. The delegates to the Constitutional Convention chose the Electoral College less because of its virtues than because of its competitors’ perceived shortcomings.

The Electoral College system was enshrined in Article II of the US Constitution, which sets forth the rules governing how the president and vice president are elected. It has been tweaked a bit in the years since, but it still basically operates in the same way it did when it was first adopted in 1789. The constitutional amendment required to change or replace this system would have to be passed by two-thirds of both houses of Congress, and then ratified by the legislatures of three-quarters of the states—38 states out of fifty. Alternatively, two-thirds of state legislatures could ask Congress to call a Constitutional Convention.

It is very rare for 38 out of fifty states to agree on anything in the US. Of almost 12,000 amendments proposed since the country’s constitution was ratified in 1788, only 27 have been adopted (the last one of any substance was passed in 1971, lowering the voting age to eighteen). Ten of those amendments constitute the Bill of Rights, ratified by states in 1791. “We have an amendment process that’s the hardest in the world to enact,” Aziz Rana, a professor of constitutional law at Cornell University, wrote in 2021. “That’s the reason why it’s basically a dead letter to enact constitutional amendments. You have to have rolling supermajorities across the country to do so.”

Under the Electoral College system, candidates must focus their campaigning on closely contested “swing states.” This time around, the Democrats are spending their time door-knocking, advertising, and stumping in states like North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Arizona, but not in states they can expect to win comfortably like New York, California, and West Virginia. Switching to a popular-vote system, however, would bring cities like Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York into contention. As I pointed out in a 2019 article for the Bulwark, the fifty largest metropolitan areas would replace the swing states as the focus of campaigning, which would mean that large swathes of the US voting population would be simply ignored. In a polarised environment, the American public is unlikely to agree to such an outcome in practice, even though 65 percent of them say they prefer a popular-vote system in theory.

Some advocacy groups have suggested that the constitutional-amendment hurdle could be sidestepped entirely if states simply require their electors to vote for the winner of the popular vote rather than the winner of their states. The National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC) would, in effect, try to implement popular-vote rules while keeping the electoral college. There are numerous problems with this approach, and were it adopted, it would almost certainly precipitate a constitutional crisis and a host of furious legal challenges.

But there are also practical reasons such a proposal would fail. For such a system to work, states with over 270 Electoral-College votes combined would need to agree. Currently, only seventeen states, with a combined total of 209 EC votes, have signed up, and getting the additional 61 votes looks nearly impossible. Red states are unlikely to agree to replace an electoral system that favours the GOP with one that is likely to advantage their opponents. It may be even less democratic than the present system. As Princeton University researcher Alexandra Orbuch has argued: “The states involved would effectively be silencing the rest of the country. And as we have seen, that means that the right-wing of the country would lose its voice in elections and thereby in policymaking essentially eradicating the diversity of thought and plurality that is so key to the American political character.”

Unfortunately, we have not heard the last of this debate, because activists persist in believing that any system that advantages their own party must be fairer by definition. All the alternatives on offer have problems of their own. We could try them all before agreeing that the one selected by the founders was indeed the least undesirable option available, but this would not be a valuable use of time and resources. Given the insurmountable obstacles to changing the US electoral system, critics of the electoral college would be better off directing their energies into formulating better campaign strategies under the existing system.