Podcast

Podcast #249: The (Other) Scandal at Oberlin College

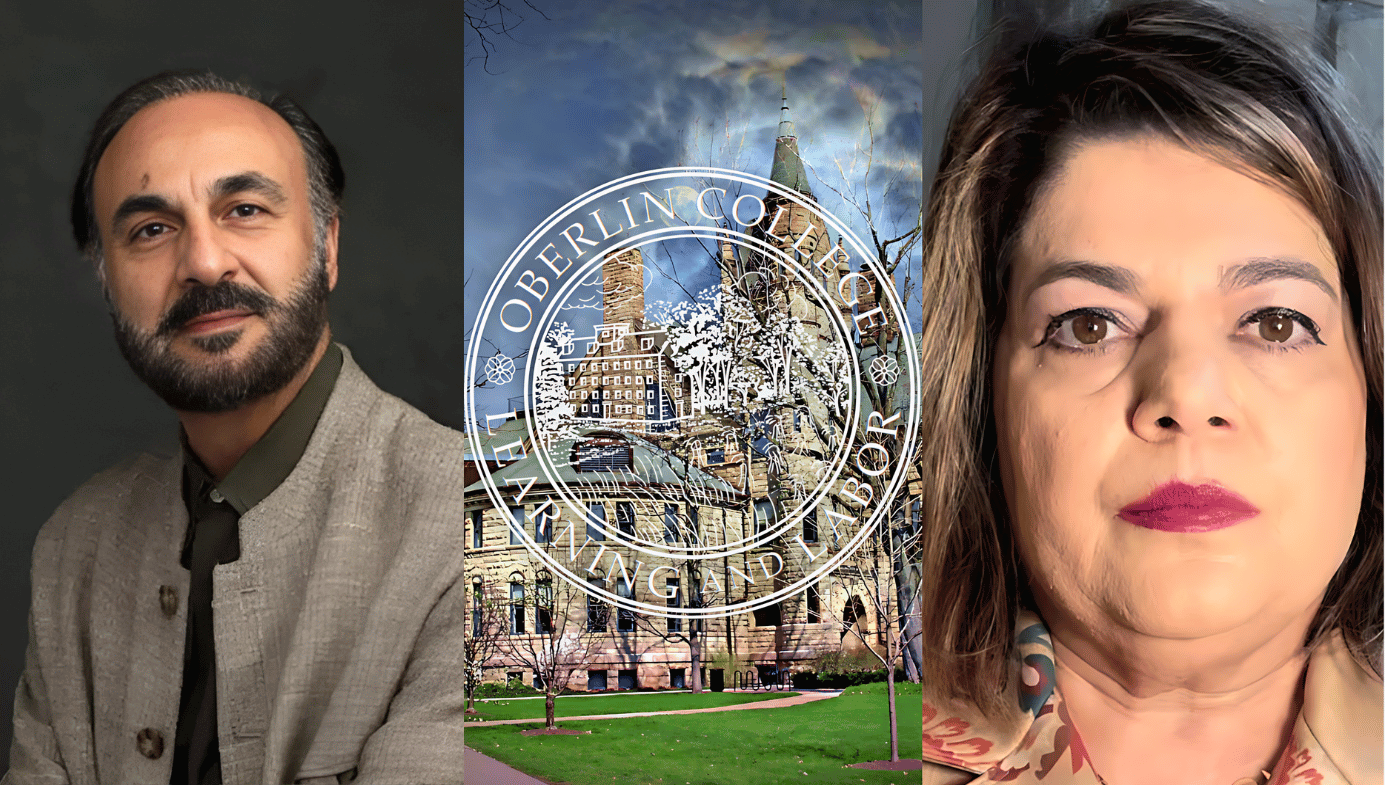

Jonathan Kay speaks with Roya Hakakian about the rise and fall of Mohammad Jafar Mahallati, a former Iranian official who’d presented himself to Oberlin as an agent of peace and ‘forgiveness.’

Jonathan Kay: Welcome to the Quillette podcast. This week we’ll be talking about a scandal at Oberlin College, the private liberal arts college in the Ohio town of the same name. But it’s probably not the same scandal that you’re thinking of. Many of you will remember that Oberlin became internationally infamous in the late 2010s, when the college’s administrators falsely accused the owners of a local family-run bakery. But my guest today won’t be talking about that Oberlin scandal, but rather a completely separate scandal involving a former professor of religion named Mohammad Jafar Mahallati. I say former because, in November 2023, Mahallati was placed on indefinite administrative leave for likely reasons that you’ll be hearing about from my guest, Roya Hakakian.

Roya, as regular readers of Quillette will know, is the author of an August 8 article entitled, The Professor, His Nemesis, and a Scandal at Oberlin, which not only chronicles the dark past of Mahallati, but also provides a lesson on modern Iranian history that’s necessary to appreciate the saga of the man’s rise and fall.

That story began in the 1980s, when Mahallati, the son of a powerful Iranian cleric, became Iran’s ambassador to the United Nations, where he served as an international apologist for the tyrannical Islamist regime that had come to power in the 1979 Islamic Revolution. This was a period during which Iran was fighting a brutal war against neighbouring Iraq. As Roya discusses in her article, Iran also was waging a murderous campaign against anti-regime elements within the Iranian population—especially a group called the People’s Mojahedin Organisation of Iran, a dissident group that had allied itself with Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi regime as part of its failed campaign to topple Ayatollah Khomeini.

During the last months of the Iran-Iraq war in particular, the Iranian government engaged in a brutal campaign of dissident suppression—killing several thousand imprisoned Mojahedin members, as well as communists who expressed anti-Islamist beliefs.

The mass execution of so many Iranians stands as one of the many bloody human rights stains on the record of Iran’s theocracy. But it also had a personal connection to the “nemesis” in the headline of Roya’s article. That would be Lawdan Bazargan, an international Iranian human-rights activist whose own brother was one of the thousands killed during that 1988 mass execution of political prisoners.

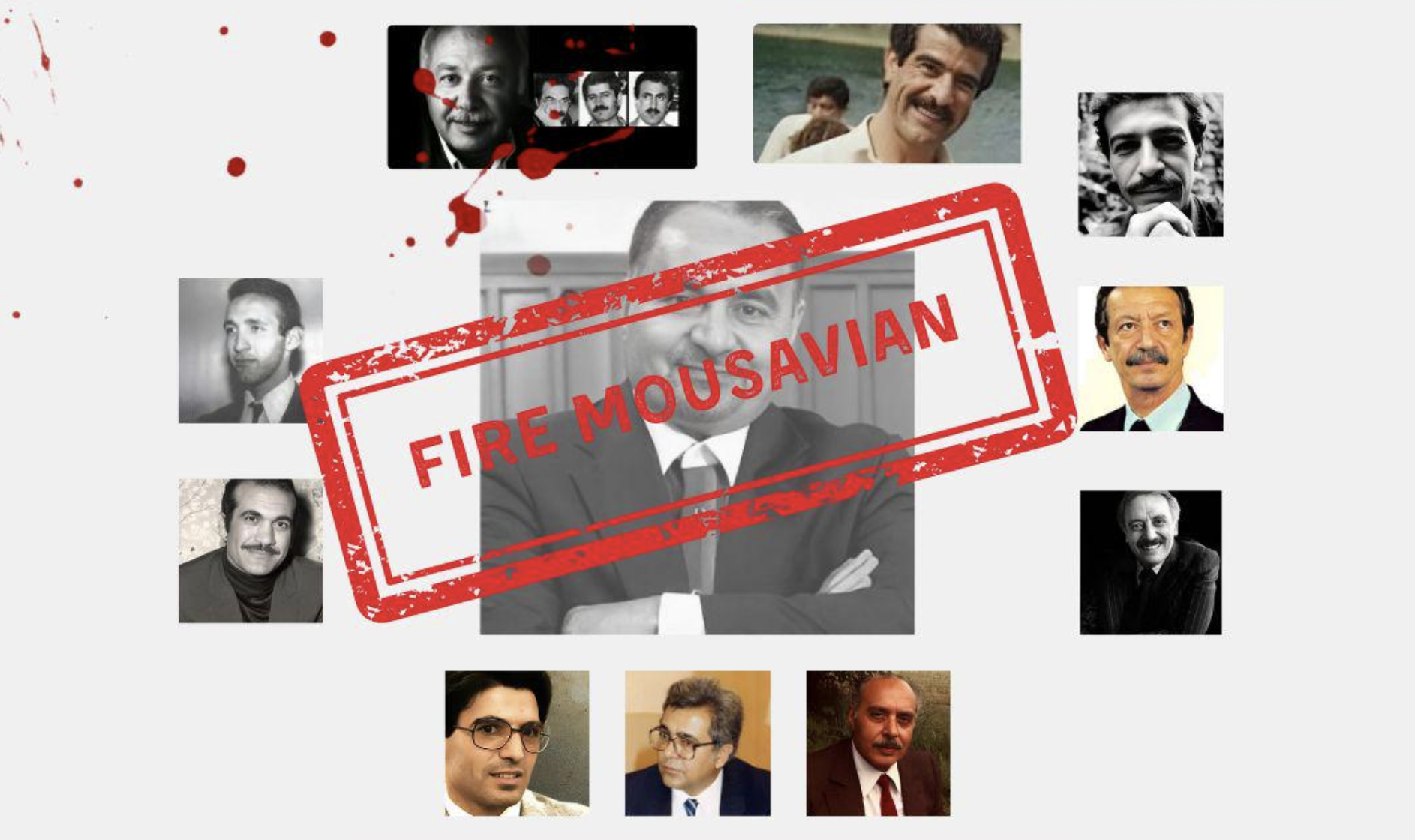

And, like many other Iranian activists, Bazargan was appalled that the regime’s UN mouthpiece during that dark period, Mohammed Jafar Mahallati, should enjoy the gilded comforts of a sun-dappled Midwestern arts college campus—not to mention being feted by the Oberlin community as a supposed champion of “peace, reconciliation, and forgiveness.”

As Roya will discuss, Mahallati’s career at Oberlin began almost 20 years ago, after he charmed the college’s former president, who’d been invited to Tehran as part of a civil-society peace-building project. Shortly thereafter, Mahallati installed himself at Oberlin, where he suggested to locals that he’d somehow been an opponent of the very regime he served. He even established an annual “Day of Friendship,” as it was called, complete with rainbow flags and peace T-shirts. As Roya documented at length in her Quillette article, Oberlin’s administrators were apparently so charmed by Mahallati that they ignored his dark past, as well as his questionable academic qualifications.

Later on, it emerged that he’d been the subject of multiple harassment accusations—though it should be added that these have never been proven in court or anywhere else. Moreover, Mahallati, whose job as a UN ambassador had required him to defend Iran’s fatwa against Salman Rushdie, as well as its exterminationist rhetoric against Israel, was also using his educational perch at Oberlin to, at least occasionally, encourage students to pursue religious conversion to Islam—or so he admitted when he was expressing himself in Farsi.

Indeed, one of the subplots here is that Mahallati had a message of peace, love, and brotherhood when speaking to fellow Oberlinians in English, while adopting a decidedly Shiite Islamist tone when speaking in Farsi.

I’ll be discussing all of this and more with this week’s guest, Roya Hakakian.

Jonathan Kay: It’s a complicated subject, so I want to start maybe with the president of Oberlin who got this started. Could you tell us a little bit about Nancy Schrom Dye? Am I pronouncing her name correctly?

Roya Hakakian: Yes, [the late] Nancy Schrom Dye became the president of Oberlin, I believe in 1993 [Correction: Dye became Oberlin’s President in 1994].

And during the time of her tenure, and I think it was probably after [the] 9/11 [terrorist attack], she was approached by a group that wanted to bring about reconciliation or peace-building with Iran and the Middle East [more generally].

Jonathan Kay: So she travelled to Iran and had a fateful meeting with the man who’s at the centre of your article. Could you describe how those two met?

Roya Hakakian: So Nancy Dye ends up going to Iran with the group Search For Common Ground, a non-profit organisation that has had deep roots in different parts of Africa. After 9/11, it turned its attention to the Middle East—Afghanistan, Iraq. When it looked like Iran was going to be the next target of the United States in that region, Search for Common Ground started to actively spearhead efforts to prevent war with Iran.

Jafar Mahallati was a consultant with Search for Common Ground. And so, when Nancy Dye goes to Iran [in 2004], it’s with a clear understanding that Mahallati has been instrumental in planning the president’s trip. And then by the time she returns in 2006, the agenda is far more focused and designed by the Iranians, namely by Mahallati, whose real career outside of Iran began when he was appointed the ambassador to the UN in 1987.

In 1980, a war between Iran and Iraq had begun. And by 1987, it had already been in its seventh year. It was one of the costliest wars and least known wars of the 20th century. But [the Iranian leader] Ayatollah Khomeini was still resolute that he wanted to carry this war out. He wanted to conquer Baghdad. He wanted to go from Baghdad to Jerusalem. And that’s the definitive moment of Jafar Mahallati’s career at the United Nations.

Jonathan Kay: One thing I’m curious about is how his name was on the radar for such a prominent post. You mentioned in the article that his dad was an Ayatollah.

Roya Hakakian: Exactly. So his father had been a major Ayatollah in the city of Shiraz, which is one of the five major cities in Iran. And he had his own charitable centre, his own estate, his own seminary, and as a result of his father’s position, Mahallati himself had been appointed a Hujjat al-Islam—one degree below an Ayatollah.

Jonathan Kay: In the modern progressive idiom, he was born into privilege.

Roya Hakakian: In religious privilege, which, after the 1979 revolution…

Jonathan Kay: …that was the currency of the realm.

Roya Hakakian: Precisely. He instantly, overnight, became part of the ruling elite of Iran.

Jonathan Kay: Did you find anything in his record that indicates he was a dissident against the regime?

Roya Hakakian: Everybody in Iran, from the moment you enter the country, the cab driver who picks you up from the airport, starts to complain and be critical of the authorities. So the point is, how seriously had he been critical of the regime, and did it mean that he had absolutely pitted himself against the authorities, or was [he simply] voicing criticisms that everybody, to some degree or another, was voicing?

So far as I know, he wasn’t voicing any criticism that could create a rift between him and the regime. The impression that he had given at Oberlin to the locals and to his colleagues had been that he really meant to do it [rebel against the regime], that he was an anti-regime believer, but couldn’t [go through with] it because he was deeply attached and dedicated to the cause that his father had created, to the charitable organisation, to the mosque, and to the estate.

Jonathan Kay: Amid all of the horrors that were created by the Islamist regime, there’s one that was at the centre of the activism of the woman who, at least indirectly, was responsible for unmasking this professor at Oberlin. It unfolded in the last months of the Iran-Iraq war.

That backdrop is important because of the pretext that the regime used to commit the killings. Could you talk about this murderous outrage that took place in 1988?

Roya Hakakian: So in 1987, Mahallati gets sent to New York to be the Iranian ambassador at the UN, and in the summer of 1988, it becomes very clear that some sort of peace needs to be struck between Iran and Iraq, because this war cannot go on anymore.

This is at a time when one of the most serious, if not the most serious, opposition [group], which is the [People’s Mojahedin Organisation of Iran]… it was an Islamist group that had, prior to the revolution, endorsed Ayatollah Khomeini, but then after the revolution had a falling-out with him and became part of the opposition. So in 1988, they are very sensitively positioned, because Iraq had given them a headquarters. They’d been homeless for a while. And Saddam Hussein, the former president of Iraq, realised that this is the most important opposition to the Iranian regime, and says, he’ll provide them with weaponry and use Iraq [as their base]. But once [the Mojahedin] have been disbanded, once they have been pushed back, once they have been conquered and defeated, the regime has to try to figure out how they’re going to avenge themselves.

And so Ayatollah Khomeini, in summer 1988, issues a fatwa. And it basically allowed for the prison authorities to do away with the members of the Mojahedin, especially the ones who were not repentant or had not recanted. But what happens is that there is an interim committee that comes into existence to carry out this fatwa, which was, by the way, headed by Ebrahim Raisi, the late President of Iran, whose helicopter crashed a couple of months ago, because he was at the time, the attorney general in Tehran.

And so he and four others become members of this committee that goes from prison to prison to identify the members of the Mojahedin who are going to be the subjects of the fatwa. And what happens is that in the process of building this killing machinery, they realise that now that they are at it, they’ll kill communists who are not repentant either.

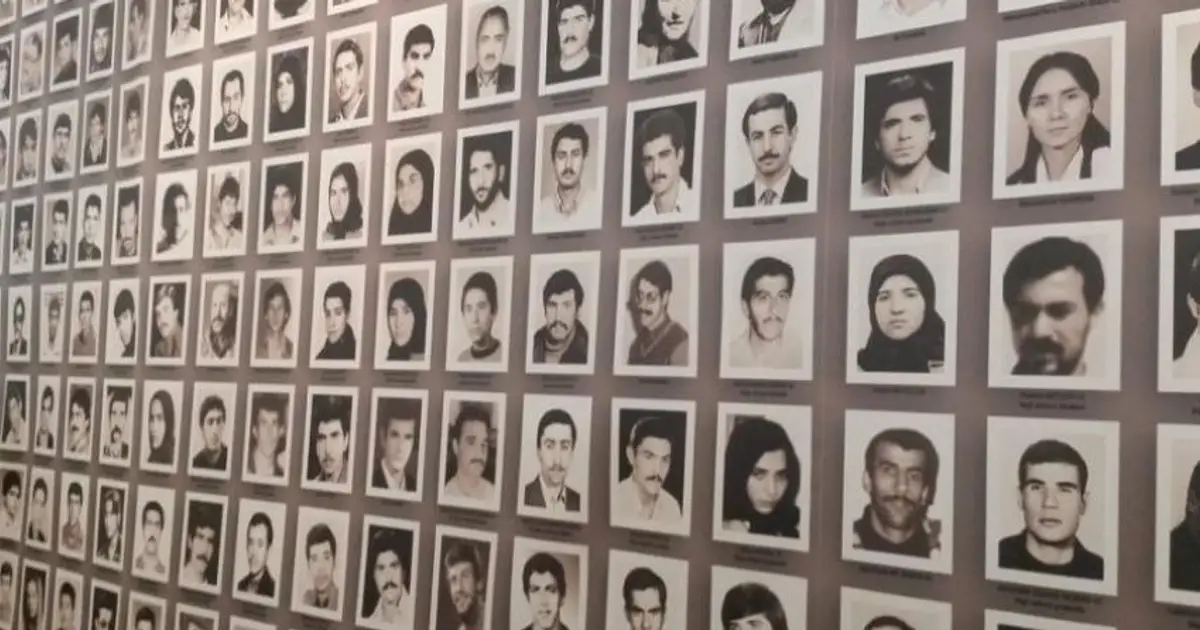

All told, within the span of 10–12 weeks in summer 1988, 3,000–5,000 political prisoners, primarily members of the Mojahedin, but also communists, are killed summarily. Some of these prisoners had already served their sentences and had expected to be released. Their families were planning on coming to pick them up.

One of the people who was killed was the brother of the woman, Lawdan Bazargan, who becomes a key player in bringing down Mahallati at Oberlin.

Jonathan Kay: As you say in the article, the state made a point of not permitting funerals or releasing the bodies because they were scared that those funerals would become flash points for dissent. And so you could see how, beyond the ordinary trauma of any family losing a son, there was also the trauma of not having closure.

Roya Hakakian: The families were not only shocked, but they were also told that if they were going to demand any sort of accountability or explanation, that they would be arrested.

He promised he’d never comment on a woman’s appearance, but this time, @jonkay just couldn’t help himself. See my reaction. ✌️

— Masih Alinejad 🏳️ (@AlinejadMasih) August 4, 2024

To those in the West who say we’re not at war with the Islamic Republic, let me tell you: the Islamic Republic is at war with us.

The world has turned… pic.twitter.com/xZPQkYXa7G

Jonathan Kay: To be clear, Mahallati is not accused of killing anybody by his own hand or touring prisons and identifying individuals to be killed. [Instead], he’s at the United Nations. And, again, I’m going to jump forward a little bit because later on, he started saying that—well, I guess, through his lawyers—he said, I was in New York the whole time. I didn’t know any of this.

In that respect, he seems to have been caught out because in your article, you source the diaries and official records of a former Iranian president, [Akbar] Rafsanjani, who indicated that actually in 1988, at the time the worst abuses were taking place, he [Mahallati] was back in Tehran, I think at least twice, meeting with the President, with officials at the highest level in Iran. Is that correct?

Roya Hakakian: Yes, that’s correct. He was in New York. Maybe while he was in New York, he didn’t know [about the killings], but it’s very unlikely that when he travelled to Iran during the peak of the killings in summer 1988, and was meeting with the highest echelons of the regime, that he didn’t hear. But then the other thing that makes it really unlikely for him not to have known is that his father was one of the top elite ayatollahs in Iran.

And the issue of the massacre in prisons in summer 1988 became a religious flash point. And that’s because Ayatollah Khomeini, who had been the leader of the Iranian Revolution in 1979, and then the supreme leader in 1988, when all of these things were happening, had a successor.

Jonathan Kay: Montazeri? Was that his name?

Roya Hakakian: Montazeri was his name. And [Hussein-Ali] Montazeri and Ayatollah Khomeini had a huge falling-out, because Montazeri was against the killings. He called the members of the committee that was going around to prisons and trying the prisoners and then sending them to their death… He said to every single one of them that history will not forgive them and that they were committing a major sin.

And you hear in the recording that they’re responding sheepishly [to him]—that, you know, it’s very difficult to stop now because they have started the process and people have already been recruited and the machinery is moving forward, and it’s very difficult for them to stop. And Montazeri really aggressively tells them that their job is to stop this process because they are committing a sin.

Jonathan Kay: Is there any evidence that Mahallati was allied with the Montazeri faction that opposed mass killing of dissidents?

Roya Hakakian: There isn’t.

Jonathan Kay: And in the United Nations, he was a mouthpiece for the official [regime]. He made public statements in defence, as I understand it, of the fatwa against Salman Rushdie. Is that correct?

Roya Hakakian: Yes.

Guess who defends Khomeini’s FATWA against #Salman_Rushdie?

— Masih Alinejad 🏳️ (@AlinejadMasih) August 12, 2022

Mahallati the Islamic Republic’s former ambassador at the UN who is now a professor at @oberlincollege. He has said that the punishment for blasphemy is death.

The US must be tough on terror.

pic.twitter.com/uKYET164lx

Jonathan Kay: You didn’t have to do investigative work to find out that he had defended the regime’s death sentence. This was all out in the public record?

Roya Hakakian: Yes… transcripts of his various statements and interviews. [Yet] it was not a hard thing for Oberlinians to justify this because they said that was his job. He was serving that government and he needed to say those things.

Jonathan Kay: What did he say about Israel or I think, [as he called it], the Zionist state?

Roya Hakakian: That the Zionist state should be annihilated. What really deeply interested me and continues to interest me is: How do these characters get into the United States—become an American citizen for God’s sake—and end up benefiting from the goodwill and trust of the most liberal elements within our communities and academia—people who should have said to themselves, by virtue of their high education, This guy served a very bad regime. Let us look into his past a little bit and try to figure out who he is, why he’s here, and whether he deserves our trust or not. But none of that happened.

Jonathan Kay: Have you ever met him? Is he one of those people who just charms everyone?

Roya Hakakian: I haven’t met him, but I have heard unanimously, even from people among those who’d objected to his promotion at the college—everyone said he was magisterial, charismatic.

Jonathan Kay: He seems to have a certain brilliance in knowing what a certain kind of progressive, well-educated American person wants to hear about a culture he or she doesn’t quite understand.

Roya Hakakian: 100 percent.

Jonathan Kay: He seems to have cottoned on to that aspect of American academic progressive culture very quickly. Did he learn that at the United Nations?

Roya Hakakian: In the 1970s, he had been in the United States, doing an undergraduate and a master’s degree here. And that’s the specific quality of a certain class within the current regime in Iran: they have been educated in the United States. They know exactly the language that the US academic community wants to hear. And so Mahallati was one of them, but he’s not the only one.

Even from the time that Khomeini was in Paris and was trying to communicate with the West, the people who ran his communications were that exact class of people who’d been Islamists educated in the United States or the West and knew precisely how to talk and how to appeal.

Jonathan Kay: You make the point that by the time [Mahallati] got to Oberlin and became a professor there, his academic record was still very thin. Is that correct?

Roya Hakakian: Yes, he had received a PhD by the time he arrives at Oberlin in 2007. And he very quickly expected to be promoted and be tenured. [But] his publications were deeply lacking. He has not built any academic relationships, so the people who are recommending him were celebrities.

Jonathan Kay: So one of my observations, I’ve done a lot of academic scandal stories, is that sometimes it’s easier for people to pull the wool over everybody’s eyes at a small school. I’ve done stories about Smith College, and I did a huge story on Haverford, which has barely over a thousand students.

And one thing you find at small schools is that one or two personalities can very easily dominate campus. Had Oberlin instead been Harvard, or Yale, or Princeton, which have tens of thousands of students and thousands of faculty, would it have been more difficult for Mahallati to pull this stunt? Because you would have had dozens of native Farsi speakers in all sorts of departments who were like, Hey, I know this guy.

Is it because Oberlin is so tiny that, first of all, he was able to extend his charm on a personal level—because at these schools, often everybody knows everybody else? It’s like a big high school. And also there just weren’t that many native Farsi speakers who could call him out.

Roya Hakakian: What would have held him back at probably a larger university wasn’t so much his past as it probably would have been his academic credentials.

Jonathan Kay: You did a number of interviews, some on the record, some off the record. It sounds like Mahallati didn’t fool everyone at Oberlin. And there was at least one department head who said, you know what, this guy’s completely unqualified, right? And that person talked to you.

Roya Hakakian: [But] these people weren’t asking, who is this guy who was affiliated with the Iranian regime… can we trust him? It wasn’t any of that. Rather, there were a couple of people who just believed in the value and the merits of scholarship, and were expecting anyone who was coming into their space to have those merits and to bring those values.

So they were expecting what was expected from anyone, which was: We want everybody who takes the position of, say, professor to have published fifteen peer reviewed articles; if not, say, twelve; if not, ten. But Mahallati was lacking. His writing was bad. His English writing was very poor. What he was trying to pass as articles were some poetry translations that he himself had published.

Jonathan Kay: One of the themes that comes out of your piece is that… while, obviously there was Islamophobia in the United States after 9/11, no one disputes that… But, to a certain extent at a place like Oberlin, and for a guy like Mahallati, the backlash against Islamophobia played to his advantage because everyone was so eager to counter Islamophobic narratives. So they went overboard and gave him a free pass. And that included the Iranians who protested on [Mahallati’s] behalf, once people wanted to get him ousted.

Roya Hakakian: You and I know that there has been, especially after 9/11, a certain degree of Islamophobia in the United States. And the question then becomes, how do you validly and reasonably counter Islamophobia? The path that Oberlin College and Oberlin as a town took was to counter Islamophobia with Islamophilism.

In other words, if there is an irrational opposition to Muslims or anything having to do with Islam, we’re going to go to the other extreme.

Jonathan Kay: There’s a concrete example of this phenomenon where, as I understand, at one point, they were looking for a job for him and he ended up at the Department of Religious Studies.

Roya Hakakian: Department of Religion, I think they called it.

Jonathan Kay: And their in-house approach was, we’re not here to convert people to one religion or another. It’s not church, or synagogue, or mosque. We’re here to teach the religious traditions. To educate people about where religions come from and what they believe and whatnot.

Roya Hakakian: And so people can question them, and analyse them, and understand them.

Jonathan Kay: But that wasn’t Mahalatti’s approach, apparently. You found a document in which he bragged that he was helping people convert to Islam. Is that correct?

Roya Hakakian: He said that in an interview in Iran. So the podcast interviewer asked him, So, you’re in the position where hundreds of infidels come through your door on an annual basis. What do you do with those infidels? Do you try to convert them? And he says, you know, some of them, very few, not a big number, see the light in Islam or recognise the path of life, and I helped them convert. That interview makes very clear the expectations that Iranians had of him was to be a proselytiser.

Jonathan Kay: There was a twist, though. He told the interviewer that, as Islam sweeps countries like United States, I want to make sure that Shia Islam gets a fair shake. He wasn’t just trying to convert people. He was also trying to convert them to a very specific kind of Islam.

Roya Hakakian: Precisely. And that’s not something that he says in the interview. He writes that in a couple of articles. He’s a theoretician of Shiism in the West. So, in other words, what he’s really positing in these articles is how does Shiism expand its horizons at a time when Islam is on the rise, and will inevitably—this is what he says—claim an Islamic empire in all of North America?

Jonathan Kay: Just to be clear, there’s no evidence that he was promoting violent jihad in North America.

Roya Hakakian: To the contrary. He has a keen understanding of how to speak and appeal to Western audiences. The moment he presents himself as a peace-loving Muslim who is misunderstood in the West is how he will win hearts and minds. And that’s his strategy. That’s why the title of his [work] was Peace, Friendship, and Forgiveness Studies.

Jonathan Kay: To be fair, for many Muslims, [Islam] is a religion of peace, but for the Ayatollahs, maybe less so…

Roya Hakakian: Yes, the issue isn’t with individual Muslims. The issue is with the ideology and those who are trying to propagate it.

Jonathan Kay: There is a certain genius of branding here, which goes beyond this guy. Like, once you label a whole field of studies, like peace and forgiveness studies and reconciliation studies, anti-colonial, anti-racism studies, it almost makes it impossible to refute some of the often suspect—and, in some cases, extremist—propositions. Because who doesn’t want to be a fan of something called “forgiveness studies”?

Part of the story goes beyond this one guy, to this academic racket that once you brand yourself according to this milk-and-honey-type labelling system, that’s your brand, too. It’s like, I’m kosher because I’m an expert in peace and forgiveness studies. What kind of bigot would criticise that?

Roya Hakakian: Yes, but it’s not his invention. There is a class of Islamists who have realised that, first of all, in order to win hearts and minds, they need to infiltrate the academic space, and second, that this violent message that Islamists are spreading in the region cannot sell. And, therefore, they need to soften it. They need to adapt it to the local tastes.

And, therefore, they talk about victimisation—the United States, Israel, Western powers have exploited and colonised them, and so on and so forth; or that they’re misunderstood; or both. And then, that their message is only a message of peace, reconciliation, friendship, and forgiveness.

This isn’t just something that Mahallati has tapped into. It’s something that an entire Islamist intellectual class is doing.

Jonathan Kay: It may not be something that he invented, but he seems to be particularly adept at it. As I understand, he created some annual Peace and Friendship Day where he’s giving out T-shirts and stuff in Oberlin.

Roya Hakakian: Yes.

Jonathan Kay: This is a guy who understands the combination of progressive naïvete, but also mass-retail American politics. A lot of Iranians come to North America and they’re extremely successful entrepreneurs. He seems to channel some of that.

Roya Hakakian: Yes. And people in Oberlin still talk about Friendship Day! And that’s his invention.

Jonathan Kay: Did they hold hands and make a big circle? That sounds awful. Did unicorns fly through the air? The whole thing sounds childish. Look, I like friendship. Friendship’s great. But…

Roya Hakakian: Were he not a Muslim from Iran, it is very unlikely that people would have fallen for it. But because he was a Muslim from Iran, because there was this sense that these are the people that our government wants to go bomb, they gave [him] a pass. And what I’m really hoping that we can do isn’t that we become suspect instantly of Muslims, but that we subject them to the same degree of analysis, expectation, scepticism, that we subject [everyone else] to.

Jonathan Kay: How did Ms Bazargan finally take this guy down?

Roya Hakakian: Well, I think a combination of factors. One was that in the process of looking into his background, the lawsuit that a former student of his had filed…

Jonathan Kay: This goes back to Columbia.

Roya Hakakian: Columbia in 1998.

Jonathan Kay: Oh, by the way, my favourite part of that subplot was when he tried to claim diplomatic immunity.

Roya Hakakian: Right. It had been ten years since he had been at the UN, but he still claimed diplomatic [immunity]. And the best part—this didn’t make it into the article—is that he actually did manage to get a letter from the Iranian office at the UN mission to say that he was a consultant…

Jonathan Kay: Well, he clearly hasn’t fallen out with the regime if he’s able to call in that favour. But how did [Bazargan] get the ball rolling to bring him down?

Roya Hakakian: A group of alumni from Oberlin were looking into Mahallati’s past, and some of them seemed to really zero in on his antisemitic statements from his years at the UN…

Jonathan Kay: [You mean] calling for Israel’s annihilation?

Roya Hakakian: Calling for Israel’s Annihilation. So that was one. The other was the surfacing of that lawsuit…

Jonathan Kay: Which was settled out of court…

Roya Hakakian: Yes.

Jonathan Kay: And a non-disclosure agreement.

Roya Hakakian: Exactly. But the problem was that until Lawdan Bazargan showed up and the families [of victims of the 1988 massacres] started to protest, Oberlin had no knowledge of the lawsuit or of the anti-Israeli statements from the UN. And then [there was] the Congressional inquiry into anti-Israeli statements and antisemitic statements [on American campuses]. So all of that together made it very difficult for the college to hang on to him.

The other thing is that over the past five or six years, Oberlin has been in the media spotlight in a very negative fashion, and they just didn’t want one more [scandal].

Jonathan Kay: I mentioned it in the introduction, but the whole thing with Gibson’s Bakery is similar—where you had a shoplifter claiming racism and the university basically lining up to attack an innocent local business.

Have any heads rolled among senior administrators at Oberlin for either of these two scandals? They seemed to just give you radio silence.

Roya Hakakian: I sent dozens and dozens of interview requests to various professors, deans, Mahallati himself, and nobody was responding to me. Only a few professors who had retired agreed to talk to me and a couple who wouldn’t speak on the record. I was already at Oberlin, and was wondering what was happening.

The head of media relations called me to her office and said, everybody has been forwarding the emails you’ve sent to me. And I have to say that we’ll not give you an interview because we don’t think you can be an objective reporter. And I said, why?

And they said that in 2020, you were among several hundred people—and the list included Shirin Ebadi, the Nobel Laureate from Iran, Azar Nafisi, the writer of Reading Lolita in Tehran. All of these people had signed this petition demanding that Mahallati be fired.

So I was among them. So she said, you know, we don’t think you can be objective. I said, you’re correct. I cannot be objective about Mahallati because I know things and I have access to sources that you don’t know because you don’t have the language [skills] and you’re not familiar with the culture.

But what I am objective about is: I want to know why it was that you all embraced him. Why it was that you lowered your standards for this particular guy?

Jonathan Kay: And they never gave you an answer?

Roya Hakakian: They never gave me an answer. She said, we’ll think about it. You think about it. We’ll be in touch.

Jonathan Kay: Mahallati… where is he now? Is he hanging around Oberlin, having coffee at Gibson’s?

Roya Hakakian: He’s ... I don’t know where he is.

Jonathan Kay: Thank you so much for your time.

Roya Hakakian: Thank you, Jonathan.