Islam

Disuniting Australia

What happens when the values of multiculturalism conflict with homophobic, misogynistic, and deeply anti-democratic strains of Islam?

In the foreword of Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr.’s classic 1991 book The Disuniting of America: Reflections on a Multicultural Society, he asks, “What happens when people of different ethnicities, origins, speaking different languages and professing different religions, settle in the same geographical locality and live under the same political sovereignty?” He answers his own question by making a dire prediction: “Unless a common purpose binds them together, tribal antagonism will drive them apart. In the century darkly ahead, civilisation faces a critical question: What is it that holds a nation together?” Schlesinger also presciently notes the increase in racial identity politics, which he calls the “cult of ethnicity,” warning that it “exaggerates differences, intensifies resentments and antagonisms, drives even deeper the awful wedges between races and nationalities. The endgame is self-pity and self-ghettoization.”

Schlesinger homes in on what he sees as the risk that multiculturalism may lead to “ethno-centric separatists,” who view Western history as little more than a catalogue of crimes: “The Western tradition, in this view, is inherently racist, sexist, ‘classist,’ hegemonic; irredeemably repressive, irredeemably oppressive.” This simplistic reduction of Western culture, values, and norms to oppressive power systems will be familiar to anyone steeped in critical theory. While, in fact, Western cultural norms are themselves diverse and filled with internal tensions, in this view, they are simplistically equated with assimilationism, Eurocentrism, and neo-colonisation.

In the epilogue to his expanded second edition (1998), Schlesinger notes that identity politics, once the province of the Right, has a new left-wing manifestation. The Left once espoused universalist ideals: now they obsess over group differences. Multiculturalism, according to Schlesinger, can mutate from its “mild” form—which seeks to “redress a shameful imbalance in the treatment of minorities”—into a “militant” variant, which “opposes the idea of a common culture, rejects the goals of assimilation and integration, and celebrates the immutability of diverse and separate ethnic and racial communities.” What he perceives here is the emergence of an essentialist view of cultural groups.

The concerns and cautions that Schlesinger raised have recently been thrown into sharp relief here in Australia, given the local responses to the 7 October terrorist attacks in Israel. In the wake of the Hamas attacks, our country’s much-vaunted self-image as a harmonious multicultural society is looking a little less credible and Schlesinger’s dire warnings seem especially prescient. Two recent incidents have highlighted our society’s fracture lines.

The first occurred in November 2023, when a preacher at Sydney’s Islamic Al Madina Dawah Centre described the Hamas terrorists as “freedom fighters.” In response to the sharp criticism that ensued, a spokesman for the centre justified the preacher’s words with an appeal to a pan-Muslim identity: “Our Centre, and the entire Muslim community, stand by anything that is authenticity [sic] quoted from the Koran and Sunnah.”

The second incident took place later that month, when pro-Palestinian protesters in Melbourne targeted visiting Israelis whose family members had been killed or captured by Hamas. Again, this resulted in widespread condemnation. Prime Minister Anthony Albanese described the actions of the protestors as “beyond contempt.” Labor MP Julian Hill commented: “This is Australia. This is not who we are”—invoking the idea of Australia as a cohesive and tolerant multicultural society. But is Hill’s statement aspirational or purely descriptive? In other words, is he talking about what Australia is or what he would like it to be? Whether we consider Australia a successful multicultural society depends on how we define success and what elements we think of as intrinsic to multiculturalism.

One of the problems is that there have been relatively few empirical studies of how multiculturalism works in practice. To understand Australian multiculturalism, we need to examine such questions as: how much influence immigrant groups have on government policy; which groups have the greatest influence and why; whether religion plays a significant role; and how we balance group rights against individual rights.

Yet, although some of these questions clearly have concrete answers, as Ruud Koopmans has noted, both critics and supporters of multiculturalism prefer to use normative arguments, focusing on whether multiculturalism should be good for a society, rather than on how it is actually working within that society. As Koopmans comments, “[t]here is certainly a wide gap between the available evidence and the sweeping statements made in the public debate.” This is exacerbated by the fact that, in the current climate, academics have few incentives to undertake empirical studies of multiculturalism, since they risk being accused of racism if they unearth any negative consequences. Yet it is vital to gather evidence on these issues—partly to ensure the wellbeing of women and minorities within the smaller ethnic groups themselves. Koopman writes:

If critics [of multiculturalism] are right, we should, for instance, find a greater frequency of attitudes and behaviors that sustain gender inequality within minority groups that live in countries with multicultural policies, especially if these include rights pertaining to cultural behaviors with a gender dimension. However, no such empirical studies have been undertaken.

Australia is, of course, a very different society from Schlesinger’s America and has a very different history. It is the largest country in Oceania, and a member of the Commonwealth. Made up of six states and two major territories, Australia was not federated until 1901, and currently has a population of just over 26 million. By the time Australia was colonised by the British Empire in the late eighteenth century, its First Peoples had already been occupying the continent for some 50–55,000 years. The country has had a deeply troubled post-settlement history, with long-standing grievances about the dispossession of Indigenous people and its continuing impacts. Much early European settlement was driven by the exportation of convicts from Britain and Ireland. Then, in the 19th century, free settlers arrived, especially after the discovery of local gold.

In Australia, racism has often been overt, such as in the early 20th century when the official “White Australia” policy encouraged European immigration and discriminated against Asians and Pacific Islanders. This policy was not wound down until the 1970s. At the same time, Australia has always been a magnet for immigrants fleeing war or poverty or simply seeking a better life, and in recent decades strongly multicultural policies have helped drive immigration. There are, however, deep similarities between Australia and America: both are “melting pot” societies with deeply rooted racial tensions, both have a history of population growth through immigration, both imported forced labour, and both have mistreated their indigenous peoples. But the specifics and scale of all these things are very different here in Australia.

In the mid-1970s, Australia established a number of policies supporting and promoting multiculturalism and immigration, for both economic reasons (the country needed skilled workers) and humanitarian ones. By 2011, Australia’s Federal Government Multicultural Policy included passages such as: “The Australian Government celebrates and values the benefits of cultural diversity for all Australians, within the broader aims of national unity, community harmony and maintenance of our democratic values”; and “The Australian Government is committed to a just, inclusive and socially cohesive society where everyone can participate in the opportunities that Australia offers.”

The most recent figures published by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, for the 2022–23 financial year demonstrate just how committed our government remains to these values. Last year:

- There was a net annual gain of 518,000 people, as a result of immigration.

- Migrant arrivals increased by 73 percent to 737,000 from 427,000 arrivals a year ago.

- The largest group of migrants was temporary visa holders (554,000 people).

- Migrant departures decreased by 2 percent to 219,000 from 223,000 departures a year ago.

(The top three countries supplying permanent immigrants to Australia were India, China, and the Philippines.)

So, at the official policy level, there is strong support for multiculturalism, but what about popular attitudes? Beneath the veneer of public policy and official pronouncements, is Australia a racist country? And what happens when the values of multiculturalism conflict with a democracy’s core values of civic participation, freedom of association, tolerance of others, and equal rights?

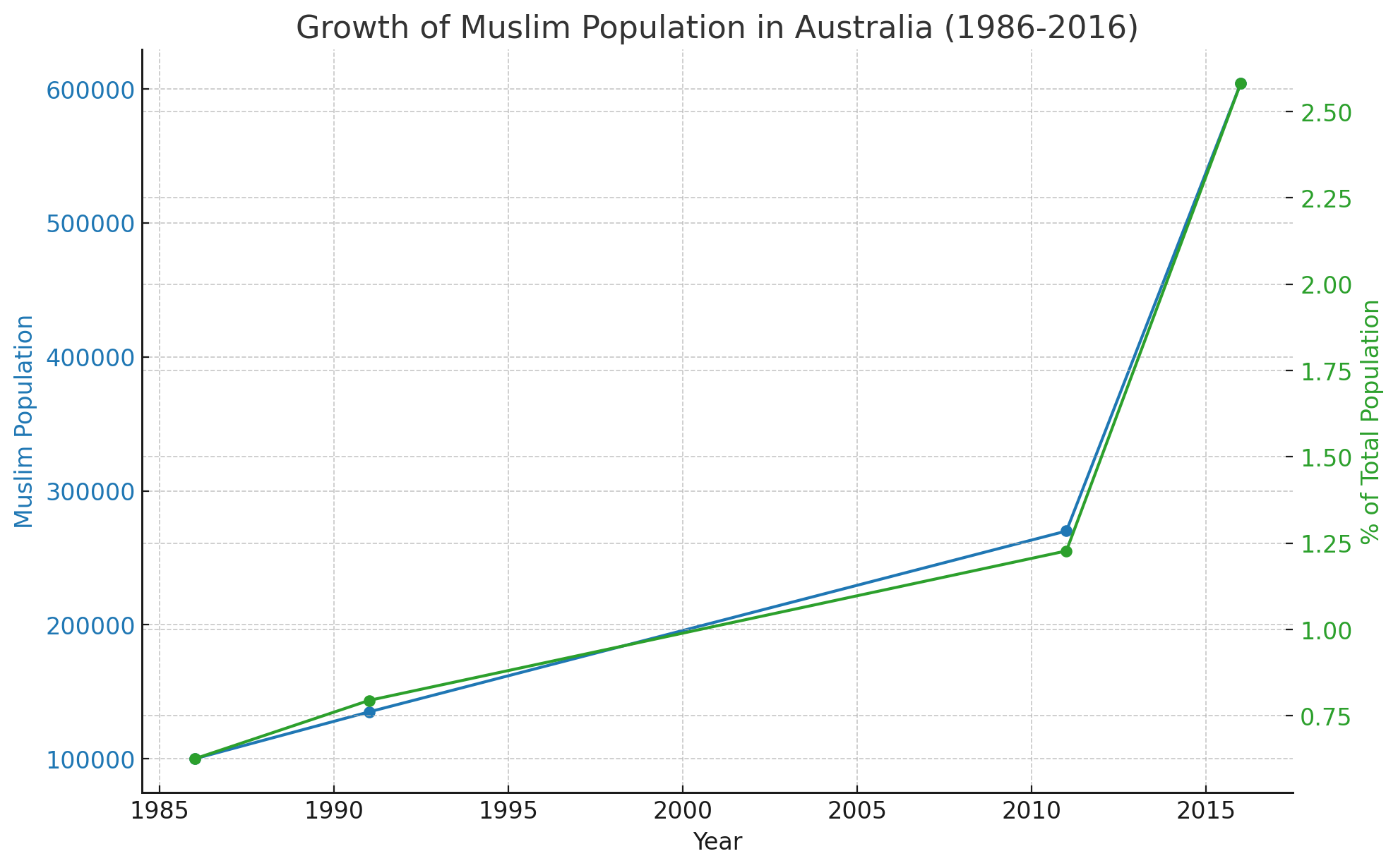

To begin to answer some of these questions, let’s focus on a particular flash point, especially since 7 October 2023: Islam. There has been rapid growth in Muslim immigration to Australia since the end of the twentieth century. As researchers Halim Rane et al point out:

Between 1986 and 1991, Australia’s Muslim population experienced a growth rate of 35 percent primarily due to immigration. During this period, nearly 100,000 Muslims arrived in Australia, mostly from the Middle East …. This was followed by a further doubling of the Muslim population by 2011. According to the 2016 census, there are 604,200 Muslim Australians (2.6% of a total population of approximately 23.4 million).

Over the past twenty years, there have been multiple surveys, studies, and articles on Muslim migration to Australia and on accompanying fears of rising Islamophobia. One of the most significant of these was the “Challenging Racism Project 2015–16 National Survey.” This survey showed that there is strong support for cultural diversity among the general Australian population. Yet, some academics have claimed that such results only hide the deeply racist and colonial underbelly of Australian attitudes. They are troubled by what they describe as,

contradictory political trends of celebrated diversity, triumphalist claims about freedom, alongside pro-assimilationist views and stoked Islamophobia. This is within the context of a stalled multicultural project that has not sufficiently challenged assimilationist assumptions and Anglo-privilege.

Such views are representative of a flurry of recent scholarly articles that argue that Muslims are seen as an out-group and that Islamophobia is prevalent in Australia—facts that these academics believe run counter to Australia’s self-congratulatory claims that multiculturalism has been a success here.

Such scholars espouse a culturally essentialist, identity-politics-infused view of multiculturalism. Liberal Muslim academic Elham Manea argues that their platform has four main features:

1. It combines multiculturalism as a political process with a soft legal pluralism, dividing people along cultural, religious, and ethnic lines, treating them differently on account of their “cultural differences” and in the process setting them apart and placing them in parallel legal enclaves.

2. It perceives rights from the perspective of the group; the group has rights, not the individuals within it. It insists that each group has a collective identity and culture, an essential identity and culture, which should be protected and perpetuated even if doing so violates the rights of individuals within the group.

3. It is dominated by a cultural relativist approach to rights (in both its forms, as strong and soft cultural relativism) and argues that rights and other social practices, values, and moral norms are culturally determined.

4. It is haunted by the white man’s/woman’s burden caused by a strong sense of shame and guilt for the Western colonial and imperial past and by a paternalistic desire to protect minorities or people from former colonies.

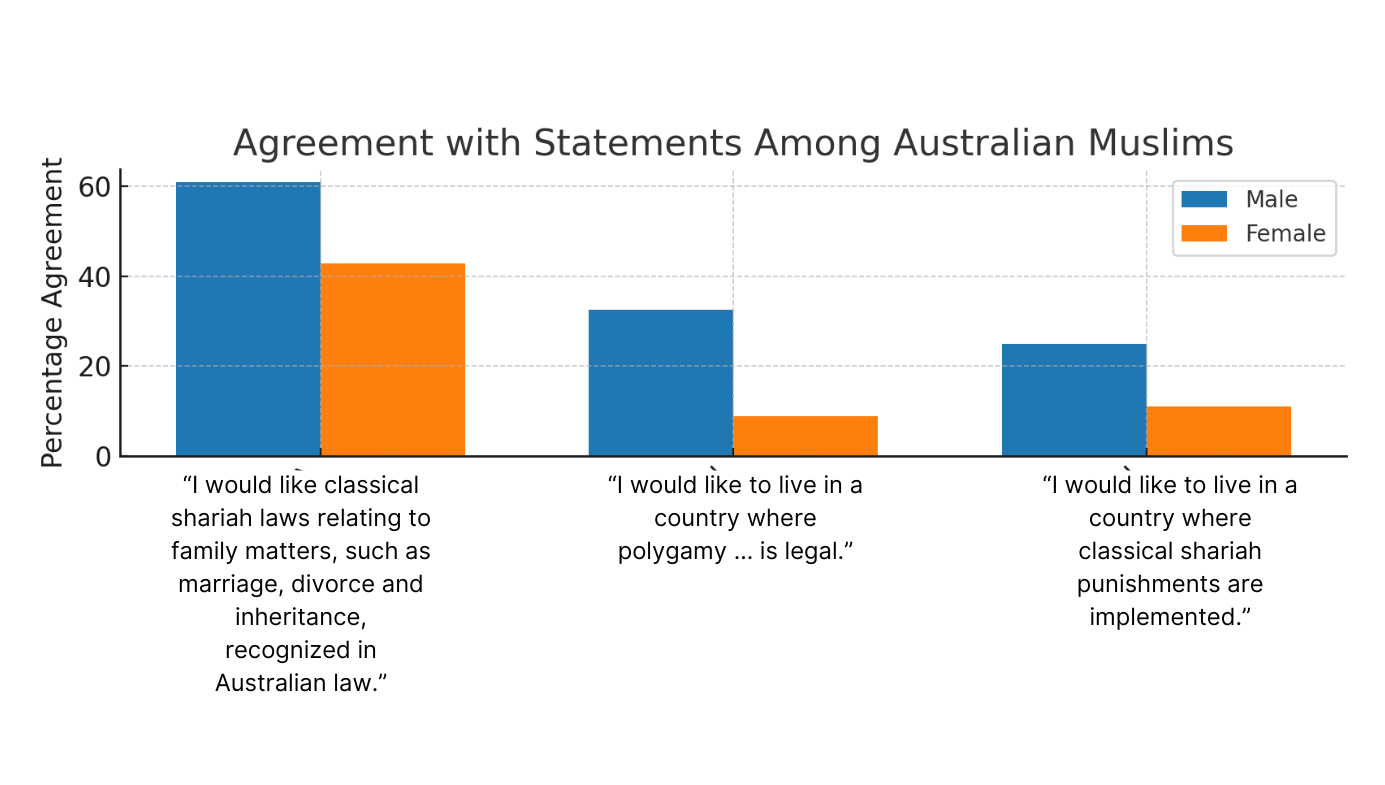

So, what are these alternative cultural and moral norms to which such scholars want us to take a relativist approach? A 2019 study of the attitudes of 1,034 Australian Muslims by Halim Rane and his colleagues could provide a clue. According to the results, the vast majority of both male and female Muslim Australians can be categorised overall as “Liberal” (almost 90 percent); while about three-quarters are “Progressive,” and just over half “Secular.” These findings are reassuring. However, when the participants were asked fine-grained questions about specific issues relating to shariah law, the results were more troubling and there were marked differences between the attitudes of men versus women.

For example, 60.9 percent of Muslim men—and only 42.9 percent of Muslim women—agreed with the statement, “I would like classical shariah laws relating to family matters, such as marriage, divorce and inheritance, recognized in Australian law.” Likewise for the statement: “I would like to live in a country where polygamy … is legal,” the response was 32.5 percent Strongly Agree/Agree for males, against a mere 8.8 percent for females. Finally, 25 percent of Muslim men agreed with the statement, “I would like to live in a country where classical shariah punishments are implemented,” as opposed to 11 percent of Muslim women.

These attitudes have worrying potential implications for sex discrimination and oppression of and violence towards women. There has been little research into such issues as child marriages, FGM, and tolerance of domestic violence towards women and children within these communities. Anyone undertaking such research would rightly fear being accused of Islamophobia. However, without this data, it is impossible to know what—if any—actions government authorities should be taking to protect Muslim women.

These issues are exacerbated by the fact that Muslim interest groups are often dominated by men and that these men are often treated as authoritative representatives of Australian Muslims. This is an especially acute problem in the case of imams and other Islamic leaders, who may be seen as the authentic voices of their communities and become the people who liaise with the government on their behalf. In her study “Muslim Youth and the Mufti,” Silma Ihram observes that:

There has been a tendency both internationally and in Australia for Islamic leaders to represent themselves as teaching a type of Islam that is purer and closer to the original teaching than their competitors, to the extent of claiming that the latter are polluting Islam with “innovation” or “bida” and therefore should be excluded from the community of believers. This activity is called “takfiring”—or naming as kufr, as an unbeliever, those who are outside of the accepted community. This is akin to excommunicating a Muslim in that they are no longer privy to membership of the Muslim community or the Global Ummah to the extent that permission to perform the ritual Hajj is denied. Added to this existing competition is a further aspect of rivalry … the essentialising of the group as a single entity may well feed into a vicious circle of dynamics within Islamic leadership trying to outdo each other in their purity and thus regression.

In a recent article on research into Islamophobia in Australia, I ask:

If, in a Muslim majority country, a minority cultural-religious or gender group (say Christians in today’s Pakistan, or LGTBQI+ individuals in Palestine or Egypt) were being discriminated against, and this was fuelled by the religious conservatism and bigotry of the majority … what would be the focus: dominance of the majority, or the nature of the beliefs themselves? What if we migrate religious conservatism and bigotry to a country where those beliefs are no longer majority or as dominant—but nonetheless remain held within migrant communities—what do we discuss? Is it the case that bigotry is accepted or dismissed so long as those holding it are the minority? Is it bad-faith “assimilation” or “acculturation,” or even “Islamophobic” to ask why some attitudes and beliefs should be acceptable in Australia today?

Unfortunately, some Australian discussions of Islamophobia frame concerns about individual rights and freedoms—especially women’s rights and freedoms—as simply signs of Eurocentric bias, xenophobia, or even a kind of “white man’s burden.” For example, the “Challenging Racism Project 2015–16” aimed at measuring,

the extent and variation of racist attitudes and experiences in Australia. It examines Australians attitudes to cultural diversity, discomfort/intolerance of specific groups, ideology of nation, perceptions of Anglo-Celtic cultural privilege, and belief in racialism, racial separatism and racial hierarchy.

The study seems to take for granted that any concerns around the potential negative consequences of multiculturalism are the result of racism or privilege—rather than legitimate worries about the safety and liberty of women, gay men, and other minority groups within the Muslim community and the influence of regressive views about women, homosexuality, etc. on Australian society as a whole.

In his 2013 study, Koopmans examines the ways in which minority migrant groups can influence cultural and religious policies. Such groups can exercise a much greater influence than their numbers would suggest, since they are often highly motivated to preserve their culture, especially when that culture is a religious one. As Koopmans notes, “Although immigrants share an interest in obtaining individual citizenship rights, not all groups are equally prone to making claims for cultural rights.” This is especially true of religious rights and exemptions. As Koopmans notes, “the largest and most controversial share of claims making on multicultural rights is about religious rights.”

As Lorne Dawson and Maarten Boudry have discussed, many Westerners, including Australians, have grown up in liberal democracies in which the influence of the church is limited. Even if they are observant, their religious observance might have little impact on their interactions with the law or with the society outside their church. Such people may assume that the link between religious rights and multicultural rights is benign. They are sceptical of the idea that religious prescriptions are likely to encroach on civil liberties and freedoms here, given the fact that religion has been in steady retreat in the face of Enlightenment and democratic norms in the West. But what happens when the “assertive” religions of migrant groups meet the fashionable cultural relativism of Western societies committed to multiculturalism?

In his 2005 essay “Shifting Aims, Moving Targets,” the anthropologist Clifford Geertz describes with concern the emergence of these “assertive” religions. He sees the latter as characterised by doctrinaire religious attitudes, as opposed to the more personal and reflective “religious mindedness” of less aggressive forms of faith. He warns:

Hindutva, Neo-Evangelism, Engaged Buddhism, Eretz Israel, Liberation Theology, Universal Sufism, Charismatic Christianity, Wahhabis, Shi’ism, Qutb, and “The Return of Islam”: assertive religion, active, expansive, and bent on dominion, is not only back; the notion that it was going away, its significance shrinking, its force dissolving, seems to have been, to put it mildly, at least premature.

Geertz links the emergence of these assertive forms of faith to the disentanglement of major religions from their social and geographical sites of origin. A person’s religious persuasion has become a mobile facet of their public identity, a characteristic of what David Goodhart called the “anywheres” (people willing to live anywhere) as well as the “somewheres” (people deeply attached to a specific locale). Of course, religious people have always travelled beyond the homeland of the faith, carrying their convictions to their adoptive countries. What is new here, Geertz says,

is that whereas the earlier movement of religious conceptions and their attendant commitments, practices, and self-identifications was largely a matter of centrifugal outreach …. the present movement is both larger and more various, more a general dispersion than a series of directed flows; the migration, temporary, semi-permanent, and permanent, of everyday believers … across the globe.

The globalisation of the major religions has led to tensions of various kinds. People who feel spiritually displaced, outnumbered, and embattled may cling to their group identity. And those leaders or groups who invoke the purest, most aggressive, strictest and most literal interpretations of that religious identity may then be able to muster believers to their cause and shape both their communities and the world around them.

And the effects of aggressive religiosity differ according to the religion concerned. Koopmans, Eylem Kanol and Dietlind Stolle examined the connection between religious observance and knowledge and tolerance of violence among Christians, Jews, and Muslims. Among the former two groups, they found that “support for violence is only weakly and ambiguously related to religiosity” and religious observance. However:

Among Muslims … both indicators of religiosity point in the same direction: observant and knowledgeable Muslims are more likely to endorse violence, and … observant Muslims are more receptive to the mobilisation of support for violence by way of scriptural references than less observant Muslims.

This link between Islam and violence is also encouraged by those Muslims who—together with some Western leftists—view Islamism as an idealised, universal emancipatory movement against the “Western liberal democratic state and the oppressive order it sustains,” as David Martin Jones and M.L.R. Smith put it in their 2014 book, Sacred Violence. Jones and Smith point out the powerful and mutually supportive relationship between “Muslim discontent” and critical theory-derived academic discourse on international relations. The former, they write, “correlates almost exactly with the analysis and transformational agenda” of the latter. Hence recently in Australia, many scholars have explicitly linked the Palestinian cause with Australia’s colonial history, as in this open letter, which was signed by hundreds of academics:

We, the undersigned academics from Australian universities, stand in solidarity with the Palestinian people. We acknowledge the Traditional Custodians of these lands and their unextinguished sovereignties; we underscore that these lands have never been ceded. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have nurtured, and continue to nurture, the diverse Countries upon which we stand. Since 1948, Palestinians have been subject to Israel’s ongoing project of settler-colonialism, ethnic cleansing, military occupation, and racial apartheid.

Schlesinger believed that there was an important difference between right-wing and left-wing versions of what he viewed as censorious “political correctness” and what we might today call “cancel culture.” While the Left, he writes, “has no monopoly on political correctness,” he astutely recognises that “Leftwing political correctness is more systematically thought out and more pretentious [than its right-wing equivalent] … It concentrates its corrective program on institutions of higher education.” Schlesinger believed that made it less powerful, since “students … are mature enough to take care of themselves and, if not, are hard to persuade of anything anyway.”

I am not so optimistic. There is a new dynamic emerging in which progressive activist academics and the university administration are allies. As Kathleen Lowrey has recently argued, this has resulted in a “New Ptolemaism,” characterised by a poststructuralism-inspired obsession with binaries and power hierarchies, combined with a narcissistic interest in taking pride in turning what seems obvious to laypeople on its head and revealing its hidden truths, known only to the intellectual elite. This has led to a strategic alliance between academics on a Foucauldian mission to uncover power imbalances and university administrators charged with eradicating discrimination, meeting equity targets, and making campus a “safe space.” As Lowrey astutely describes:

At first blush, this would seem an unlikely alignment. Scholars influenced by Foucault usually figure themselves as political revolutionaries, while administrators looking to remake the university are unabashedly influenced by capitalist models .… Where their interests intersect is in their shared contempt for the traditional university and their shared sense that nothing is more vital than deconstructing and reconstructing it along novel lines. This, I believe, has created the strange alliance one sees in so many universities where administrators take up the banner of “equity, diversity, and inclusivity” (EDI) initiatives and putatively revolutionary faculty increasingly enter the administrative ranks.

This alliance has recently been bolstered by some troubling new elements: Islamists—fuelled by their growing sense of an essentialist, religiously-inspired group identity; and advocates of decolonisation. Together, these groups are gradually coalescing into a deeply anti-Western, anti-democratic movement that will present profound challenges to the very idea of a coherent multicultural society.

In July 2024, the Australian government released a Multicultural Framework Review “Towards Fairness: A multicultural Australia for all.” The 200-page report includes 29 recommendations embedded within a discussion of key themes and challenges. The report presents a summary of reforms and initiatives designed to promote multiculturalism over the years, and notes that there has been an erosion of support for the concept. In recent decades, the authors comment, multiculturalism has become:

highly politicised, losing the substantive bipartisan support it once had. The word “multiculturalism” has lost much of the unifying impact it may have once had; it faded from government use while being exploited by far-right groups promoting xenophobic ideologies under the guise of addressing public order issues, cultural identity preservation, protecting “jobs for Australians” against “migrant encroachment,” and maintaining social stability.

But the authors of the report concede that the reservations about multiculturalism in Australia are not just the result of bigotry or racism. They state that shared “democratic values” should be a key obligation for all Australian citizens, but they note that “people do not tend to base a shared identity on an explicit understanding or acceptance of the underlying democratic values governments enunciate” and that “religious affiliation” often trumps shared civic values. They write that some people fear that multiculturalism “is fundamentally incompatible with a unity based on what its adherents call Western or liberal values… and… point to the dangers of ‘cultural relativism.’” Ultimately, however, the report reasserts faith in the original Australian multicultural vision, which is “not just about tolerating diversity but celebrating it as an integral part of the nation’s identity.” Whether this goal is realistic remains to be seen.

This article is based on a chapter originally published in German in the edited collection Die Wir-gegen-die-Gesellschaft: Warum der von Arthur M. Schlesinger vor 30 Jahren diagnostizierte Samen der identitätspolitischen Spaltung aufgegangen ist: Debattenband zu Arthur M. Schlesingers Buch ‘Die Spaltung Amerikas’ (Ibidem Sachbuch, 2024). It is republished here with the editor’s and publisher’s permissions.