Politics

The Puzzle of Generational Politics

Disenchantment is leading younger generations to embrace a politics marked by anger and alienation.

Age is a big deal. We saw just how big a deal it is from the deterioration of President Biden evident during the recent debate with Donald Trump. There’s a growing sense that the world is being run by a gerontocracy—Biden, Trump, Putin, Xi, Khamenei—worthy of the decrepit and corrupt Emperor Tiberius.

The stage is being set for a global generational conflict. As the old men strut on the world stage, they have left the next generation an almost unfathomable $91 trillion debt load, essentially forcing higher interest rates along with the threat of higher taxes and service cuts. Even in authoritarian countries, the younger generations are getting increasingly restless. And in the West, fewer than 10 percent of Americans under thirty think the country is headed in a good direction.

In most leading countries—the US, China, Japan, the UK, and the EU—a clear and widening divide has opened up between the different age cohorts that will alter our politics, arts, culture, and social norms in the decades ahead. This process is being propelled by demographic shifts unprecedented in modern history. For the better part of a half-century, populations have been expanding and getting richer. Now, we live in an era of flat and even negative population growth, and a shrinking middle class in virtually every middle- and high-income country.

The Long Tail of the Boomers

The younger cohorts inhabit a world in which the Boomer generation hoards wealth and power. This cannot last indefinitely. As usual, the first signs of this conflict come from the arts, in movies like Japan’s Plan 75, which envisions a government programme that urges people over 75 to commit a pleasant suicide for the benefit of future generations.

There are many reasons to want to get rid of the Boomers—my own generation. An aging population requires a working generation that can help foot a nation’s bills and support the elderly. We Boomers were able to do that for our parents, but younger people today may lack the resources. In the United States, fewer than 50 percent of Millennials are doing better than their parents. This is not just an American phenomenon. In almost every high-income country, Pew has found that the vast majority of parents—82 percent in Japan and 72 percent in the US—are pessimistic about the financial future of their offspring.

Compared with their parents, young people today are more likely to have a future with no substantial assets or property. A Deloitte study projects that Millennials (Americans born 1981–96) will hold barely 16 percent of the nation’s wealth in 2030, when they will be the largest adult generation by far. By then, Generation X (born 1965–80) will hold 31 percent, while the Boomers (born 1946–64) will still control 45 percent.

Boomers have greatly benefited from the economic progress made over the past 50 years. Property-led wealth accumulation has made a fifth of Boomers paper millionaires, something not likely to be repeated in the next generation. Overall, Boomers own half of the $32 trillion in US home equity. Despite a mediocre economy and high interest rates, house prices are at record highs across the US and home equity has soared to a record high of $27.8 trillion, while buyers now come largely from households with already strong credit. In Britain, one-in-four Boomers is a millionaire (in pounds sterling), mainly due to inflated housing prices. British retirees have more income than working-age people, notes a recent Resolution Foundation survey.

The Conflicted Politics of the Boomers

Being the wealthiest generation in history does not make people more willing to sacrifice for future cohorts. In America, the UK, and Europe, Boomers may skew right-wing but few seem to want to cut back on the welfare state, particularly their own pensions. Positions on pensions and retirement long championed by the Left have now also been adopted by leading figures on the New Right, from Donald Trump and Marine Le Pen to Geert Wilders. They may often be hostile to immigration, but Boomers nevertheless support welfare for migrants, as long as their pensions remain untouched.

These tensions are most keenly felt by the many Boomers who still lack the savings or pensions for retirement. Forty percent of US retirees have insufficient savings, a trend made worse by inflation, and twenty percent have already burned through their savings. Demand for more transfers could explain why some polls had Biden polling better than expected with this demographic before his ignominious debate disaster.

Taking on the Boomers while they are still so numerous and wield disproportionate voting power is political madness. Trump, like his New Right European counterparts, defends senior-oriented transfers, and he still holds an advantage among this group, who vote at almost three times the rate of younger generations. The younger cohorts—the Zoomers and Millennials—may account for almost half of the eligible voters, but they will almost certainly constitute a lower proportion of those who actually vote in November.

Moves to raise pension-eligibility from 62 to 65, as France’s president Emmanuel Macron tried to do, have been rewarded with diminished popularity. In fact, in the latest election French voters favoured a left-wing coalition that wants to reduce the retirement age to 60. In China, which is aging even more rapidly than the West, the government faces potential blowback as it tries to raise the country’s low retirement age.

Is the Gen-Xer Moment Ever Going to Arrive?

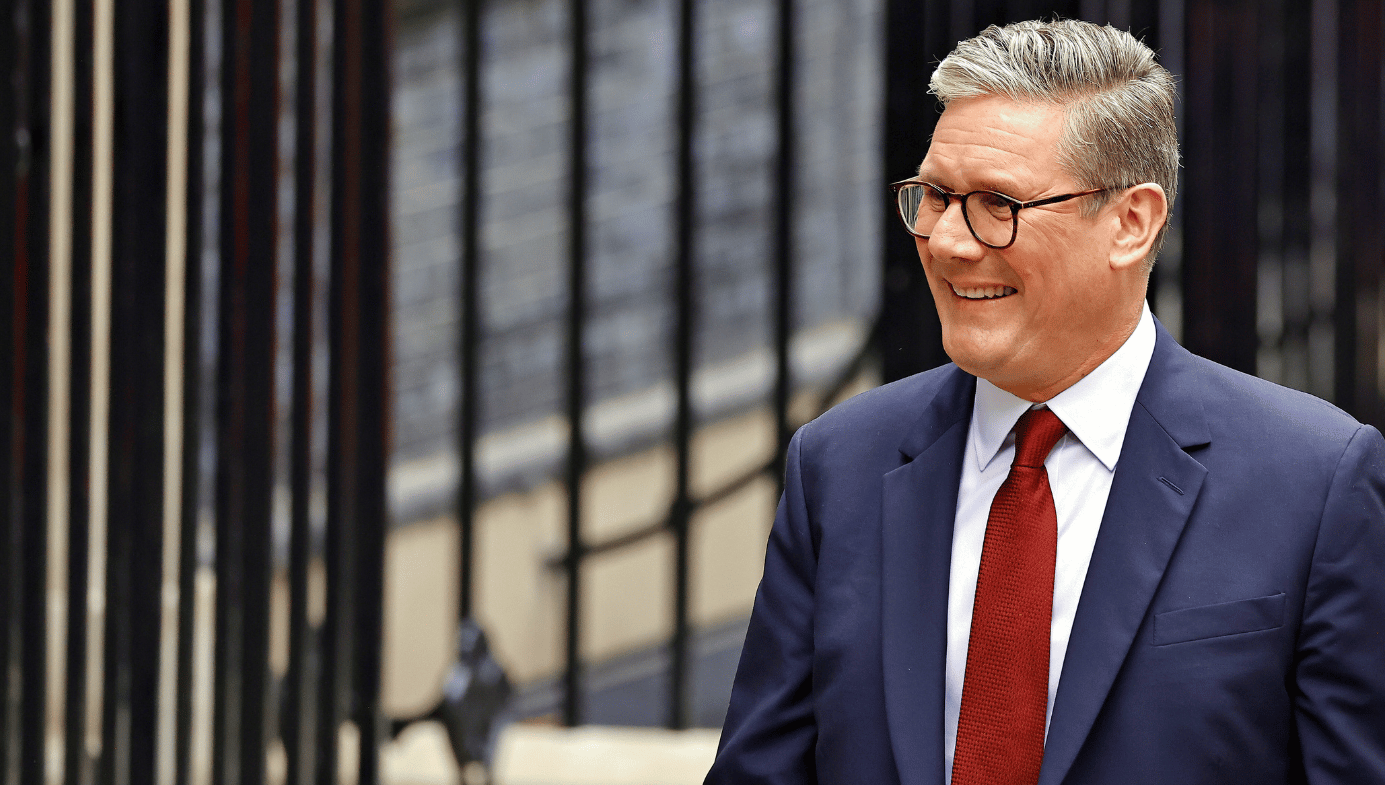

The Gen-Xers have lived in the shadow of the far more numerous and noisy Boomers. Only recently have we started to see this generation emerge with the rise of politicians like Emmanuel Macron, Wilders, Keir Starmer, Giorgia Meloni, and Justin Trudeau.

In the US, Gen-Xers are easily the most pro-Trump generation. Growing up under Reagan, they have become the most conservative of all generations. The emergence of Gen-X power is being delayed by the long rule of the Boomers, and in the case of Biden, even the generation before them. Trump’s victory over promising Gen-Xers like Ron DeSantis and Nikki Haley blocked their path to power for the immediate future. Joe Biden’s decision to run for a second term in the White House has frustrated the rise of the next generation of Democratic aspirants from the preen king of California, Governor Gavin Newsom, to more promising figures like Pennsylvania’s Josh Shapiro or Minnesota’s Amy Klobuchar.

Of course, the Boomers cannot stay in power forever. Dominant figures like the two current presidential candidates, and aging senators like Charles Schumer, Mitch McConnell, and Bernie Sanders cannot resist the march of time and biology indefinitely. Their long-term political direction may be complicated by the fact that, despite their right-wing leanings, most American Gen-Xers are short on savings and will want to guarantee their retirement prospects. As current concerns, particularly about taxes and regulations, move them rightwards, like the Boomers, they may discover the virtue of big government when they are the recipients and no longer the donors.

Are the Millennials Finally Growing Up?

Millennials have faced economic troubles from early in their lives. Many watched their parents struggle during the Great Financial Crisis while they were still in grade school. For the most part, unlike the Boomers and Gen-Xers, they emerged at a time of relatively weak economic growth. Latecomers to the tech party, they have far fewer oligarchs of their own; this year’s Forbes billionaire study shows only one percent are under 40, the lowest level in over twenty years.

Unlike the entrepreneurial, self-absorbed Gen-Xers, the Millennials have generally backed progressive causes, and their emergence as a voting force makes some Democrats giddy with anticipation. But the Millennials, like the Boomers, are far more divided than media accounts suggest.

Although they still tilt leftwards, younger voters also seem to be tugged increasingly to the right. Trump lost mightily in 2020 with this cohort (as did the GOP in the 2022 midterms), but that may be changing. Desperate to retain this cohort, Joe Biden has made repeated attempts to unilaterally cancel college debt, although these have usually been dismissed by the courts.

These gambits have not succeeded, in large part, because some Millennials have paid their debts. Most do not attend four-year colleges and the number that do has been shrinking. Across all advanced countries, roughly two-in-three young people do not have a college degree. These voters seem to be far more amenable to right-wing positions than many imagine. Driven by working-class Millennials, the percentage of young voters identifying as Republicans has been on the upswing since 2016. Trump is even gaining among educated voters who rejected him last time.

In Europe, as much as a third to two-fifths of young people support parties—and policies on immigration and climate—often characterised as far-right. In France, for example, younger voters supported Marine Le Pen last time around more than Macron. These patterns have been repeated in recent elections in Italy, Argentina, Sweden, Belgium, The Netherlands, and Spain.

How Millennials Are Screwed

Millennials have every reason to be upset. They are far less likely, according to US Census Bureau data, to own a home. In Australia, where house prices are particularly out of whack, real-estate industry insiders are now hoping to persuade older Australians to leave their homes by the age of 67 and relocate to another country. The empty properties would be then added to the rental pool, no doubt swelling the profits of the speculative classes. YIMBYs across the Anglosphere frequently vent their frustration at even progressive Boomers, who they see as hoarding precious resources and wealth, particularly in elite urban areas.

The potential for economic marginalisation is being made worse by the rise of artificial intelligence. A college education, once seen as the ticket to a middle-class life, is now increasingly considered a waste of money. Even the “geeks” are already proving to be extremely vulnerable to what economists call “skills-biased technological change.” Eighty-two percent of Millennials fear AI will reduce their wages, and according to McKinsey, at least twelve million Americans will be forced to find new work by 2030.

Millennials face a world in which economic opportunities appear to be fading. They face an environment where many good jobs are disappearing while they have to cope with high rents and exorbitant tuition fees. They may not see many benefits of things like EV mandates, which benefit richer, older customers who can afford them but not younger people forced to buy what are likely to become increasingly expensive used models.

What Happens to the Zoomers?

Conventional wisdom, particularly among progressives and their cheerleaders in the mainstream press, suggested that Zoomers (born after 1997) would follow the Millennials’ trajectory, but instead they have developed their own views. As my younger daughter, aged 20, tells me: “Don’t worry Dad, we hate the Millennials more than the Boomers.”

More than Millennials, the Zoomers have inherited a negative world created by their predecessors. Even in the US, which has done somewhat better than its rich-country cousins in the post-COVID era, Zoomers are experiencing a crisis of confidence about the society they are inheriting. One recent survey concluded that most thought they were living what surveyors described as “a dying empire led by bad people.”

This is not surprising given the media environment these young people inhabit. According to a Lancet study, the majority of Zoomers see the planet as doomed by climate change. Many, particularly the educated elite, have been indoctrinated in feminist and transgenderist doctrines that are ill-suited to helping them prepare for family life or even marriage.

Increasingly, the Zoomers live in an age of familial and gender confusion. Gallup reports that more than 28 percent of all Zoomer women identify as LGBTQ+, more than twice the rate among Millennials and almost three times that among young men. In places like South Korea and Japan, men and women seem to be evolving into separate and often hostile tribes.

Being the first generation of true “digital natives” is not exactly making Zoomers happy either. The stunningly disturbing work by Jean Twenge has revealed in detail the depressive symptoms among American K-12 students over the past two decades. Today, half of US students state that “they can’t do anything right” and that they “do not enjoy life.” Since 2009, the percentage of high-school students suffering from depression rose from 30 percent to over 50 percent among women and from 20 to 30 percent among males; the number of youngsters considering suicide has spiked, particularly among females, of whom nearly 30 percent claim to have these thoughts.

From the Gen Z chapter of *Generations*. And no, we can't continue like this. https://t.co/nd5TZYNTpu

— Jean Twenge (author of GENERATIONS, iGEN) (@jean_twenge) June 21, 2023

Like the Millennials at their age, the Zoomers still lean to the left, but their political trajectory remains confused. Although much is made of young students’ embrace of Hamas, poll data show that economic factors and alienation from current institutions are also major factors in Zoomer disenchantment. Unsurprisingly, many in the US are attracted to unconventional figures like Robert Kennedy, Jr., who is running first among them in some national polls. They are also deeply divided by gender, with women markedly more progressive than men, particularly at elite colleges.

Zoomers constitute the most “disengaged” workforces in the high-income world, with many delaying their transition to adulthood. In the US, some 40 percent of recent graduates are underemployed in jobs where their college credentials are essentially worthless. In the UK, employers fret about a diminishing Millennial work ethic; roughly a third doubt that they will reach their career goals. Almost half of all adult Americans under 30 still live with their parents. Across Europe and the UK, large proportions of young workers are neither in work nor in school.

These trends can even be seen in East Asia. Japan, once the heartland of workaholics, has witnessed the rise of the shinjinrui, or the “new race,” who have rejected steady work for an easy life, often living with their parents and spending their time travelling, playing video games, and pursuing hobbies. Lately, a similar phenomenon has spread elsewhere in Asia, including China, where many educated Millennials, faced with diminishing prospects for the country’s increasingly beleaguered middle class, have abandoned striving in favour of “lying flat.”

The Future of Generational Politics

In the coming years, generational politics will likely accelerate alienation and polarisation. Faced with hard economic prospects and pummelled by inflation, many seem poised to embrace radical change. Indeed, recent surveys suggest that Zoomers, the face of the demographic future, are the most disillusioned generation, seeing less opportunity for themselves while coping with escalating food prices, high rents, and car-insurance costs.

These sentiments could be decisive in November and in ways not generally anticipated by political operatives. Overall, according to a recent Harris-Harvard poll, barely a third of voters under thirty identify as liberals, while half described themselves as moderates or conservatives.

Like their American counterparts, Europeans under thirty are also shifting to the right, including to formerly fringe parties like the German AfD. In the last French presidential election, Marine Le Pen gained almost 40 percent of the youth vote, while Italy’s New Right prime minister Giorgio Meloni ranked first among younger voters. At National Review, Andrew Stuttaford has noted that, among voters under 25, the AfD won more votes than the Greens, the supposed favourite of young people. In 2019, the Greens did seven times better than the AfD among young voters. In Britain, youthful frustration is fuelling support for smaller parties, including Reform.

But it would be foolhardy to assume that small government will win in the coming generational conflict. Given their penurious condition and limited opportunities, many younger people are supportive of expanded government and greater redistribution of wealth. Only 40 percent of young adults around the world told Pew Research in 2022 that they view capitalism very or somewhat positively—the lowest share of any age group and 33 percentage points lower than Boomers. And as political scientist Yascha Mounk noted in his 2018 book The People vs. Democracy, while more than two-thirds of older Americans still embrace democracy, only one-in-three Millennials do.

One would hope that these challenges will lead the older generations—particularly the Gen-Xers—to back policies that will drive economic growth and restore opportunities to the next generation. But older generations may have other priorities besides hoarding their wealth and feeding at the government trough, such as embracing climate-driven policies that will prevent the expansion of the economic pie for future generations.

But as long as the stairway to opportunity and advancement is blocked, the new generations will likely embrace a kind of politics, on both the Left and Right, marked by anger and alienation. Bombast and appeals to national greatness offered by Boomer autocrats do not answer the call of the future. Older generations need to think about how to give up some of their own prerogatives as they ask ever more of the young to sustain them on their long inevitable march towards oblivion.