Art and Culture

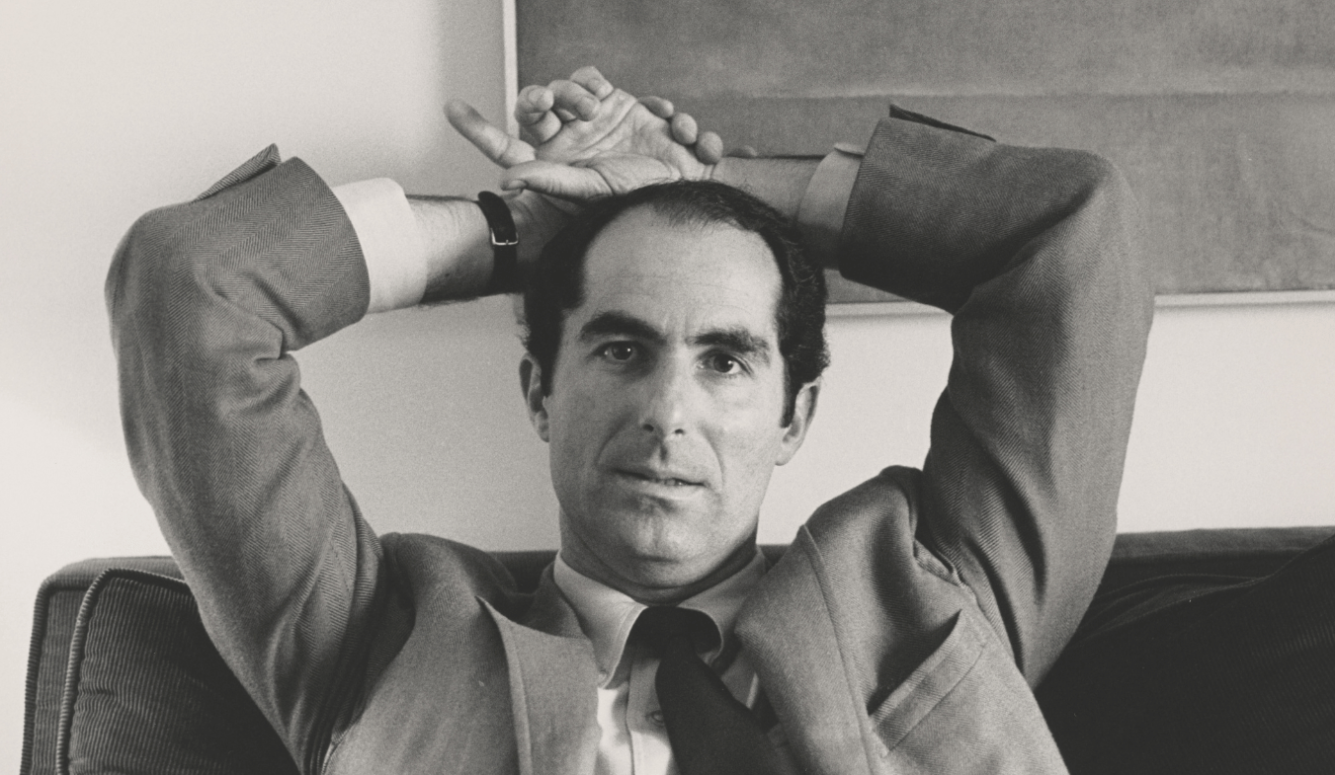

Rereading Philip Roth Today

Roth’s early works portray Jewish characters who are fearful of antisemitism in America as paranoid. He later changed his mind—and so have I.

Philip Roth had little patience with his Jewish critics. When his short stories were collected in Goodbye Columbus (1959), Roth claims that he was attacked from all sides as a “dangerous, dishonest, and irresponsible” person, largely on the basis of his portrayals of Jewish characters. In his 1963 essay “Writing about Jews,” he notes,

Among the letters I receive from readers, there have been a number written by Jews accusing me of being anti-Semitic and “self-hating,” or, at the least, tasteless; they argue or imply that the sufferings of the Jews throughout history, culminating in the murder of six million by the Nazis, have made certain criticisms of Jewish life insulting and trivial. Furthermore, it is charged that such criticism as I make of Jews—or apparent criticism—is taken by anti-Semites as justification for their attitudes … particularly as it is a Jew himself who seemingly admits to habits and behavior that are not exemplary, or even normal and acceptable. When I speak before Jewish audiences, invariably there have been people who have come up to me afterward to ask, “Why don’t you leave us alone? Why don’t you write about the Gentiles?”—“Why must you be so critical?”—“Why do you disapprove of us so?”—this last question asked as often with incredulity as with anger.

In “Writing about Jews,” Roth accuses his antagonists of being bad readers with “cramped and untenable notions of right and wrong.” His stories, he argues, are about characters who happen to be Jews, not representatives of Jewry. It’s as ridiculous to claim that his fiction makes Jews as a whole look bad, Roth argues, as it would be to say that Raskolnikov’s murder or Anna Karenina’s adultery makes Russians look bad. Roth insists on artistic autonomy: “the only response there is to any restriction of liberties is, ‘No, I refuse.’”

But there’s more going on here than an argument about the obligations of the creative imagination. When Roth’s Jewish critics called for a “balanced portrayal of Jews,” they were not simply worried about what people would think of them. They were worried that Roth’s novels would feed the antisemitism that “ultimately led to the murder of six million in our time.” Roth dismissed their concerns. In 1960s America, “neither defamation nor persecution are what they were elsewhere in the past.” Jews need to stop acting like victims, he writes, when there is no threat.

While Roth gave as good as he got, the controversy exhausted him. After a particularly vicious grilling by a Yeshiva University panel, Roth told his wife, Maggie, and his Random House editor, Joe Fox (over a pastrami sandwich at the Stage Deli), “I’ll never write about Jews again.” With the exception of Portnoy’s Complaint, Roth mostly kept his word—none of the other novels he published between 1963 and 1979 prominently feature Jews.

But in 1979, Roth published The Ghost Writer. The novel’s Jewish protagonist, Nathan Zuckerman, faces the same kind of pushback for his unflattering depictions of Jewish life as his creator did in 1963. Zuckerman has written a short story called “Higher Education,” which thinly fictionalises a money quarrel that took place in his own family. Zuckerman’s parents are appalled at this public airing of the family’s dirty laundry. “You didn’t leave anything disgusting out,” Nathan’s father, Victor, comments.

But the real reason Zuckerman père is upset is because he thinks the story will promote antisemitism. “I wonder,” his father tells Nathan, “if you fully understand how little love there is in this world for Jewish people.” Victor asks Judge Leopold Wapter, who is Newark’s third “most respected” Jew (after the mayor and the rabbi) to intervene. The distinguished jurist writes Nathan a letter that concludes: “Can you honestly say that there is anything in your short story that would not warm the heart of a Julius Streicher or a Joseph Goebbels?”

When Nathan’s mother tries to explain this viewpoint, her son cuts her off: “We are not the wretched of Belsen!” The greatest danger to local Jews, he quips, is from botched elective surgeries, not pogroms: “the plastic surgeon where the girls get their noses fixed. That’s where the Jewish blood flows in Essex County.”

The title of this section of the book is “Nathan Dedalus,” an obvious allusion to James Joyce’s Stephen Dedalus, hero of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1918). The conflict between Nathan and his father seems to represent the conflict between artistic freedom and puritanical control. When I first read the story, in The New Yorker back in 1979, I took Nathan’s side completely. I had nothing but contempt for Judge Leopold Wapter and everything he represents, and I agreed with his assessment of the status of Jews in America.

In Roth’s 1959 story, “Eli, the Fanatic,” Ted Heller wants to shut down a yeshiva inhabited by Holocaust survivors because it reminds him of a past that he considers best left behind. In suburban New York, Heller believes, the Jews have finally found what their ancestors desperately wanted—a haven from antisemitism: “the world was at last a place for families, even Jewish families.” The safety Jews enjoy in America, he writes, is exactly “what his parents had asked for in the Bronx, and his grandparents in Poland, and theirs in Russia or Austria, or wherever else they’d fled to or from.” And so, enough with “making a big thing out of suffering, so you’re going oy-oy-oy all your life”—or, as the protagonist of Portnoy’s Complaint (1969) puts it, “Do me a favor, my people, and stick your suffering heritage up your suffering ass!”

Roth had good reasons for adopting this dismissive attitude toward the idea that antisemitism was still rife in America. In his 1988 memoir, The Facts, he repeatedly emphasises that, while he did witness individual instances of antisemitism, he “never doubted that this country was mine” or felt excluded because of his ethnicity. For Roth, his American and Jewish identities were “indistinguishable.” No wonder Roth found the fear and trepidation—the “oy-oy-oy”—of his critics incomprehensible.

Nor was Roth’s experience exceptional. Growing up in the 1940s, educated in the 1950s, then coming to prominence in the 1960s and 1970s, Roth both took full advantage of and exemplified what Franklin Foer has recently called “the Golden Age of American Jews,” when American Jewry enjoyed “an unprecedented period of safety, prosperity, and political influence.” Once they were permitted to play a full part in it, Jews not only thrived, but even dominated American culture, Foer writes, through such luminaries as Ralph Lauren in fashion; Jerry Seinfeld, Alan King, Lenny Bruce, Woody Allen, and Mel Brooks in comedy; Saul Bellow, Bernard Malamud, and Norman Mailer in literature; and Bob Dylan in music. They also founded many Hollywood studios and quickly populated the previously forbidden precincts of politics, the Ivy League, and the Supreme Court. The few remaining pockets of Jew hatred had been relegated to the darker corners of American life. In his 1994 study, Anti-Semitism in America, Leonard Dinnerstein concluded that antisemitism “has declined in potency and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future.”

But now, in 2024, as the full title of Foer’s article acknowledges, “The Golden Age of American Jews Is Ending.” According to the Anti-Defamation League, antisemitic incidents rose by a shocking 360 percent after the Hamas attack on 7 October. Colleges and universities, once the refuge of bookish, scholarly Jews, are now increasingly hostile. Harvard student Shabbos Kestenheim writes that he “seldom experienced such disdain and contempt for a minority group as the way in which Harvard treats its Jewish student population.” At a Columbia University alumni event on Jewish life on campus, four high-level administrators texted dismissive and insulting comments about panellists as they spoke about antisemitism. In Toronto, two Muslim women and their young daughters were videoed proudly displaying a swastika. Even Eric Clapton has got in on the act, telling an interviewer that “Israel is running the world.” X (formerly Twitter) is now filled with antisemitic statements. Reading “Eli, The Fanatic” in 2024, it’s Ted Heller who seems naïve. Similarly, when Nathan Zuckerman’s father reminds his son about “how little love there is in this world for Jewish people,” it seems apparent that he is not wrong.

Roth does not give us much of a backstory for Judge Wapter in The Ghost Story, but we can fill in the gaps. Let’s assume—as most readers do—that Victor Zuckerman stands in for the author’s father.. Roth’s father, Herman, was born in 1901 to immigrant parents (they came from Galicia, then a province of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, now in present-day Poland). Many of his contemporaries came to America fleeing the pogroms of Eastern Europe. America did not welcome the deluge of Jewish refugees. As Dinnerstein details in his book, Eastern European Jews were often the targets of violence. In 1911, a gang of toughs in Malden, Massachusetts attacked Jews and smashed store windows, shouting, “Kill the Jews.” Victor Zuckerman and Leopold Wapter are portrayed as having had first-hand experience of this kind of violence. “My father,” Nathan tells the reader, “remembered having been rescued by one of the Wapter brothers—it could have been the future jurist himself—when a gang of Irish hooligans were having some fun throwing the seven-year-old mocky [disparaging term for a Jew] up into the air in a game of catch.”

The situation got worse after World War I. The 1920s witnessed Henry Ford’s antisemitic rantings in The Dearborn Independent and the publication of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. The influx of Jews into the Ivy League universities did not go unopposed, either. Harvard’s then president, A. Lawrence Lowell, opined that his university had a “Jewish problem,” and imposed a limit on Jewish enrolment. Other institutions quickly followed suit. The lucky few who were admitted still suffered discrimination. White-shoe law firms rarely hired Jewish lawyers and even more rarely made them partners.

Antisemitism continued to increase during the 1930s. Hitler’s denunciations of Jews as the cause of the world’s economic problems found a ready audience among many in the United States. Father Charles Coughlin began his antisemitic radio broadcasts in 1938. They eventually reached an audience of millions. In 1939, nearly 20,000 people attended a meeting of the American Bund in Madison Square Garden, at which banners were waved proclaiming “Stop Jewish Domination of Christian America.” A 1940 article in The American Jewish Congress Bulletin declared, “at no time in American history has anti-Semitism been as strong as it is today.”

So when Victor Zuckerman tells his son, “I guarantee you [antisemitism] is there. I know it is there. I have seen it. I have felt it, even when they do not express it in so many words,” he knows what he is talking about.

The idea that a Jewish writer should be discreet when depicting Jewish foibles is in line with the general attitude of the Jewish community in the 1930s and 1940s, which was not to overtly confront antisemitism, but instead “to draw no attention to themselves as Jews,” as Dinnerstein puts it.

Nonetheless, despite widespread antipathy towards them, Jews managed to thrive in America, and they did so partially by creating warm, safe neighbourhoods like the one in which Roth grew up in Newark, New Jersey, neighbourhoods in which Jewish children were largely sheltered from antisemitism—indeed segregated from gentiles in general.

The young Roth, and his surrogate, Nathan Zuckerman, grew up with the privilege of assuming that Jew hatred was a thing of the past, and so he could insist on artistic autonomy. But rereading Roth’s early fiction and The Ghost Writer today, suddenly Victor Zuckerman and Judge Wapter no longer seem the embodiments of philistinism and crabbed old age, but the voices of wisdom.

While Roth left the question of antisemitism in America alone for many years, he returned to the topic in his alternative history novel The Plot Against America (2004), and it’s clear that in the interim he had changed his mind about its prevalence. Somewhat confusingly, Roth gives the central family in this book his own name. The child narrator is “Philip Roth,” his parents are “Herman” and “Bess Roth,” and “Philip” has an older brother, “Sandy” (to differentiate the author from his creations I will use quotation marks when referring to the characters). The Plot Against America tells the story of America’s descent into fascism from the perspective of young “Philip,” who cannot understand how his safe world has collapsed.

In The Plot Against America, Roth imagines that Charles Lindbergh has won the presidency, after running on a platform to keep America out of the war against Nazi Germany. Lindbergh’s opposition to joining the Allies is explicitly antisemitic. The only people opposing Lindbergh “are the Jews.” After Lindbergh is sworn in, he signs a friendship accord with Nazi Germany, and imposes several explicitly antisemitic policies, including a “Just Folks” program, in which Jewish children spend the summer on a farm in America’s “heartland,” and a scheme called “Homestead 42.” Ostensibly designed to encourage Jewish integration by encouraging businesses to send their Jewish employees to places where there are no Jews, it’s really a scheme to dilute Jewish voting strength and destroy Jewish communities. “Herman Roth” works for an insurance firm, who want to send him to Danville, Kentucky, a small town with no Jews to speak of. “Herman” chooses to quit rather than leave Newark, but not before “Philip” gets his neighbours, Seldon Wishnow and his mother, sent to Danville as well. Unlike the “Roth” family, they go to Danville, with fatal consequences.

After Lindbergh’s plane mysteriously disappears, Lindbergh’s vice-president, Burton Wheeler, takes over in a military coup, unleashing widespread antisemitic violence. Ultimately, Wheeler is removed, order and democracy restored, America enters World War II, and everything returns to normal. But the scars, the novel implies, remain.

The ”Roth” family faces the same two options that Roth’s earlier alter-ego, Nathan Zuckerman, faced. “Philip Roth’s” parents, “Herman” and “Bess,” are convinced that antisemitism is everywhere. But their older son, “Sandy,” along with “Bess’s” sister, Evelyn, and her lover and later husband, Rabbi Lionel Bengelsdorf, dismiss that view as “ghetto” thinking and evidence of a “persecution complex.” “Herman” considers the Just Folks program a plot to separate Jewish children from their parents and community; “Evelyn” responds by “intimating none too gently that the greatest fear of a Jew like her brother-in-law was that his children might escape winding up as narrow-minded and frightened as he was.” Just like Nathan Zuckerman, “Sandy” has no tolerance for his parents’ fears.

But unlike “Eli, the Fanatic” and The Ghostwriter, there’s no doubt that “Herman Roth” is entirely right. Jews are not safe in Lindbergh’s America, and his rise unleashes the hatred percolating just beneath the surface. After Lindbergh wins, it’s socially permissible to publicly call someone a “loudmouth Jew.” The police do nothing to help when the “Roths” are ejected from their hotel because they are Jewish. The casual acceptance of antisemitism quickly gives way to violence. First Walter Winchell (the character, not the historical figure) is assassinated because of his opposition to Lindbergh and antisemitism. Then, riots and fire-bombings begin in Detroit, where the antisemitic Father Coughlin has his headquarters, from whence they spread throughout the country. Ultimately, in Roth’s novel, 122 Jews die in American pogroms, including Seldon’s mother, who is burned to death in her car.

But that is not the entire story. Antisemitism in Lindbergh’s America is not universal. There is no pogrom in Newark, and the only gunshots are fired by rival Jewish gangs. Mr Cucuzza, the “hulking” pater familias of the Italian family who move next door to the “Roths” after the Wishnows depart, is far from an antisemite. He wants to keep the “Roth” family safe. A Kentucky family called the Mawhinneys also help them without hesitation, when “Bess Roth” calls them after Seldon’s mother is murdered. When “Bess Roth” says, with deep relief, “At least, there’s some decency left in this country, “Sandy” whispers, “I told you.” He’s right, but only partly right.

In The Ghost Writer, Nathan Zuckerman does not deny that antisemitism exists in the United States, but like Sandy, he thinks the hatred is vastly overshadowed by American tolerance and mutual acceptance. In The Plot Against America, Roth reverses the polarity: while pockets of decency exist (e.g., the Mawhinneys and Cucuzzas), they are dwarfed by the murderous antisemitism unleashed by Lindburgh’s election and amplified by his disappearance. The Plot Against America proves Judge Wapter’s and Victor Zuckerman’s point: Jew hatred is everywhere.

After Donald Trump won the 2016 presidential election, The Plot Against America was widely regarded as astonishingly prescient. Somehow, in 2004, had Roth sensed that America might elect a politician who would threaten bedrock American values. The coup that ends the novel seems to anticipate the events of 6 January 2021 insurrection. But the novel also shows how deeply antisemitism is ingrained in American culture, and how little it takes for violent Jew hatred to become widespread. We underestimate this at our peril.