Books

Twilight of the Satyrs

I.

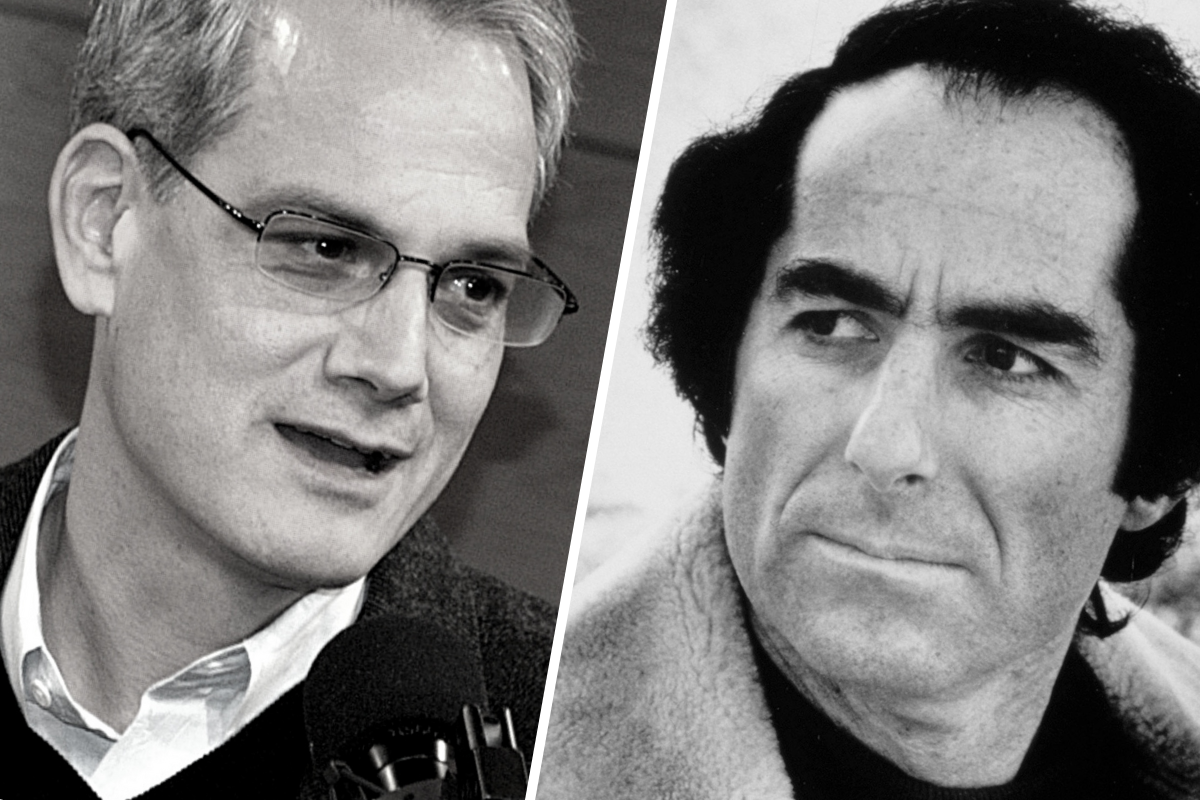

On April 18th of this year, Blake Bailey, 58, the author of Philip Roth: The Biography, was abruptly dropped by his literary agency, the Story Company. His book had been published on April 6th, and climbed to the top of the bestseller lists. But then allegations emerged that while teaching at a New Orleans middle school during the 1990s, Bailey had groomed eighth-grade girls for sexual encounters that allegedly included rape. This was followed by an allegation that Bailey had raped food blogger Valentina Rice, then a publishing executive, when they were both houseguests of New York Times book critic Dwight Garner in 2015.

Within days, Bailey’s publisher, W. Norton & Co., halted shipping and promotion of his book. On April 27th, Norton announced that it was taking it permanently out of print, and that it intended to donate an amount equivalent to the advance it had paid Bailey to organizations combating sexual abuse. It was promptly picked up by Skyhorse Publishing, which has a history of publishing books canceled by other publishers; its author list includes Woody Allen and Garrison Keillor. It is also still possible to order one of the Norton copies from Amazon, as I did a short time ago. Bailey, however, despite critical acclaim for previous biographies of Richard Yates (2003) and John Cheever (2009), as well as rave early reviews for the Roth book, may be through. The #MeToo age takes no prisoners. In June, more allegations surfaced: that Bailey, while teaching creative writing at Old Dominion University in Virginia from 2010 to 2016, had sexually harassed four women there, including a fellow professor who said he had jumped into a hot tub and fondled her while she was sitting naked there with other male faculty members on a faculty retreat (Old Dominion is currently investigating the claimed assaults).

Philip Roth died in 2018 at age 85, but Bailey seems to be dragging him along on the muddy road to permanent #MeToo besmirchment. Roth has been in trouble for decades with feminist critics, who generally judged the female characters in his novels to be simplistic near-burlesques lacking either dimension or intrinsic interest. As early as 1972, just a few years after the publication of Portnoy’s Complaint (1969), his all-time (and notoriously masturbation-focused) bestseller, Roth heard himself described as a “male chauvinist pig” on the radio. The 1960s sexual liberation that Portnoy exemplified had turned out to be only a few steps ahead of women’s liberation, as it was then called, and the women’s libbers did not regard Portnoy’s brand of male-centric erotica kindly. A literary scholar, Mary Allen, accused him of “enormous rage and disappointment with womenkind” in a 1976 academic study of male authors of the ’60s. As almost everyone in America knows, even those who have never read a page of Portnoy, that novel’s two most memorable characters, besides its eponymous first-person protagonist (one of Roth’s many fictional versions of himself), were his hysterical Jewish mother and his sexually voracious gentile mistress, game for any lewd deed involving any number of participants. Roth worked variations on those female types into most of his fiction, often adding to the mix versions of his two hated ex-wives, both of whom he portrayed, as his friend and critic, Hermione Lee, wrote in 1982, as “monstrously unmanning.” All of those types alienated feminists, who loathed the very idea that women could be types.

Added to which was the three-ring circus of Roth’s own sex life, which was either scandalous or adventurously liberated, depending on one’s point of view. The steady girlfriends, weekend visitors, adulterous interlopers, and assorted other comfort women come and go so frequently and even simultaneously in Bailey’s biography that it is difficult to sort them out or even remember who someone named “Brigit” or “Louise” or “Margot” was supposed to be (Bailey cloaked many of them with pseudonyms at their request), or when and in what context she met Roth. Most were considerably younger than he, and the age gap grew as Roth himself aged. The lengthy “romantic/sexual relationships” entry in Bailey’s index is helpful to readers hoping to sort these women out—and Roth himself kept a photo album of his former girlfriends, which undoubtedly helped jog his memory when required. It should be noted that when it was over for Roth in these escapades (and it always was, eventually, because Roth got bored easily), it was really over, and he got rid of them peremptorily and even cruelly. He told one of his dumped lovers to leave her house keys behind on her way out.

As for Roth’s two marriages, he had his 1969 alter ego, Alexander Portnoy, say, “I simply cannot, I simply will not enter into a contract to sleep with just one woman for the rest of my days.” Roth lived up to that vow and then some. He spent much of the 20 years of his relationship with the actress Claire Bloom, including five years of actual marriage (his second) from 1990 up to a beyond-acrimonious divorce in 1995, carrying on (besides his usual side flings) an overlapping 18-year entanglement with his also-married physical therapist. Foreign-born and given various monikers in various accounts of Roth’s life, she is “Inga Larsen” in Bailey’s book. Inga was the model for the middle-aged but libidinally unquenchable Croatian immigrant Drenka Balich in Roth’s National Book Award-winning 1995 novel, Sabbath’s Theater, a kind of pickleball Portnoy’s Complaint darkened by the sourness and fear of death of its protagonist, aged 64, in contrast to Alexander Portnoy’s still-youthful 33.

Roth, meanwhile, who taught writing and comparative literature as a celebrity part-time professor at the University of Pennsylvania from 1970 to 1991, slept unabashedly with his most attractive female undergraduate students, some ushered into his otherwise oversubscribed classes by wink-wink permission of his friend Joel Conarroe, chairman of the English department there. Later, Roth groused that the rise of second-wave feminism and its reinterpretation of Title IX of the Civil Rights Act had made such pleasant conquests of 19- and 20-year-olds a career-killer. “You go to feminist prison,” he told his novelist-friend Saul Bellow. By 1999, when Roth returned to academia to co-teach a course on his own novels at Bard College, his students, especially his women students, were openly complaining about a lack of “roundness” in his female characters and “certain stereotypical conceptions of gender.” He complained in turn to his friends that their “aesthetic antennae” that might sense levels of literary subtlety had been “cut” by feminist “harpies” on the faculty so that they recognized only the “political uses” of literature.

II.

So, by the time Philip Roth: The Biography emerged from Norton earlier this year chronicling his amorous meanderings in detail, there were unsurprisingly some dissenters—female dissenters, in particular—to the critical acclaim that had made Bailey’s book an instant bestseller (Cynthia Ozick, a lifelong friend of Roth’s, had called it “a narrative masterwork” in the New York Times). “Women in this book,” wrote Laura Marsh, literary editor of the New Republic, “are forever screeching, berating, flying into a rage, and storming off, as if their emotions exist solely for the purpose of sapping a man’s creative energies.” Bailey had been handpicked by Roth in 2012 as his official biographer, and granted unique access to his personal papers (locked away from the general public until 2050). Roth had just fired his previous official biographer, University of Connecticut professor and longtime friend Ross Miller (a nephew of the playwright Arthur Miller), with whom he had signed a contract for a biography in 2004. Miller had complained to others about what he judged to be a decline in the quality of Roth’s later writings (his prose “just lies there like lox”), and objected to Roth’s efforts to control the content of his interviews with his friends (Roth was writing the interview questions himself). Marsh contended—and she was not the only reviewer to do so—that Bailey had been all too happy to accept Roth’s own take on his relationships with the women in his life, without bothering to “go to the trouble of finding out what any of the women experienced from a man. They remain caricatures.” Reviewing Bailey’s book for the Jewish Review of Books, Judith Shulevitz wrote: “Roth’s women were ports of call in his voyage of self-escape.”

Francine Prose, surveying the book for the Guardian, was the most damning of all, probably because she had the hindsight advantage of writing on April 25th, after the major allegations about Bailey’s sexual transgressions had surfaced. Prose wrote that she had started reading Bailey’s book pre-cancellation purely for its entertainment value as a gossipy celebrity bio, but then:

[C]ertain sentences jumped out at me, details that seemed unnecessary, excessive, prurient or simply strange. The odd claim that childbirth had withered Roth’s first wife’s vagina [that would be Maggie Martinson, a working-class divorcée whom Roth married in 1959 and fictionalized with relentless hostility after their marriage corroded and she died in an auto accident in 1968]; the suggestion that Roth was more excited about having dinner with Robert Penn Warren and Eleanor Clark, both important writers, when he learned that their daughter was home from Yale; the description of Roth’s particular sexual acts with women mentioned by name [that would be Maxine Groffsky, the real-life model for Brenda Patimkin, the suburban-affluent Jewish girl who was the love interest in Roth’s National Book Award-winning 1959 first novel, Goodbye, Columbus—for the acts in question, see page 92 of Bailey’s book]. I wondered: was this a biography of a great writer—or of a guy turned on by a woman who let him play around with a vibrator [that would be—you can find her name on page 308]?

“In light of the allegations against Bailey,” Prose concluded, “and his neutral responses to Roth at his worst, one can’t help thinking: they found each other.” Thus, it would seem inevitable that the response of those inclined to view male sexual peccadilloes solely through the lenses of exploitation and victimization might be: Cancel them both. In 2013, after Roth had formally retired from writing at age 79, a Vulture poll had asked a spectrum of literary academics, “Who is the greatest living American novelist?” Seventy-seven percent of respondents had answered, “Philip Roth.” Now, eight years later, and after at least four years of relentless #MeToo, it would be interesting to see how Roth might fare in a poll.

In point of fact, Roth, cad and philanderer though he clearly was, was not a sexual harasser. There is no record that any of the participants in his innumerable erotic adventures was anything but overwhelmingly enthusiastic about her carnal knowledge with the Famous Writer (or, before Goodbye and Portnoy, the gangly, charming young intellectual with his graduate studies at the University of Chicago). Only one woman seems to have ever turned him down: “Felicity,” a 20-something friend and frequent houseguest of Bloom’s daughter, Anna Steiger, at whom Roth made a pass when she descended a staircase in her nightgown, which Roth took to be an invitation; afterwards he mocked her brutally for her supposed show of “virtue defiled” but did not bother her further.

At Penn, there was always a waiting list of female students dying to get into his classes, and the young women who did make the cut reported primping frantically so as to look their best. In his 2001 novel, The Dying Animal, published after it became prudent for professors not to carry on with the young ladies before the semester ended, David Kepesh, the libertine literature professor who is yet another Roth mouthpiece (he appears in several Roth novels), scrupulously waits until his grades are on file before throwing the party at his home for his students after which he will inevitably couple with one of them. Two of Roth’s late-in-life lovers, when the age gap yawned like the Marianas Trench and he was propping himself up with Viagra, even moved into the friend zone when desire faded. It helped that both—Julia Golier and Lisa Halliday—had married happily and borne children to whom Roth could play the kindly old uncle (he was adamant throughout his life about not becoming a father, and he didn’t). They were not the only women in his life to think of him fondly.

The sexual history of Blake Bailey displays similar ambiguities. From what has appeared in stories in the Times-Picayune/New Orleans Advocate, a lengthy April 29th article in Slate, and some overwrought entries in the culture blog of Edward Champion, where the first complaint about Bailey surfaced, all of his completed or attempted sexual congress with the girls he taught at Lusher Extension, a New Orleans magnet middle school, from 1992 to 2000, took place anywhere from four to eight years after they were 12-, 13-, and 14-year-olds in his honors English class there. The youngest of the Lusher alumnae with whom Bailey had sex after a lunch date in 2003 was 17, which seems shocking—except that 17 is the legal age of consent in Louisiana, she was already a freshman in college, and the sex was apparently consensual (the woman, now in her 30s, said she didn’t rebuff Bailey because she was still overawed that he had been her mentor). Another woman, whom Slate called “Heather,” now 36, was 19 and also a college freshman when Bailey, married by this time, emailed to say that he was passing through town, and would she like to meet him for drinks? He and Heather, whom he told had “blossomed” since eighth grade, ended up having sex in his hotel room. The next year, he was passing through town again, and he and Heather again had sex in his hotel room. That was the last of their physical contact, although the two continued their email correspondence until 2017.

Lusher alumna Eve Crawford Peyton alleged that Bailey had raped her in 2003, when she was 22. It was another of those I’m-in-town-let’s-have-a-drink episodes; Bailey was on a book tour for his Yates biography. Peyton was a month away from her wedding, but she agreed to meet him and then accompanied him to “the place where he was staying,” where she “really didn’t expect anything would happen,” as she wrote in an essay of her own for Slate. She wrote that Bailey had forced her into intercourse, although it must be noted that, as she admitted, this was after he had already had oral sex with her. In any event, Bailey desisted after Peyton told him that she wasn’t using birth control. He later emailed her a profuse apology, quoting Holden Caulfield—and also informing her that New York Times book critic Janet Maslin had given the Yates biography a rave review. “[M]e own mum” had watched Maslin lauding “the blakester” on television, Bailey boasted in his apology email. Peyton continued to stay in touch with Bailey until at least 2005.

A fourth former Lusher student, Elisha Diamond, met up with Bailey in a bar in 2002, when she was a freshman at the University of New Orleans; he started asking questions about her sex life, then put his hand onto her thigh. She fled—but continued emailing back and forth with him for three years afterwards. Mary Laura Newman had a similar experience while living in New York after graduating from college. Bailey was in town, the two met for drinks and dinner, and again it was the hotel room—for a nightcap. Bailey tried to kiss her, Newman said, but she reminded him that he was married and had been her eighth-grade teacher. She also said she learned from him—before exiting the room feeling “degraded”—that “things had gotten weird” in similar fashion between him and at least two other of his former Lusher students. One of the things all those young women had in common was that their mothers had apparently never told them that when a man invites you to be alone with him in his hotel room, he has only one thing in mind.

Whatever one might think of all of this, none of it exactly adds up to sexual “grooming,” which is a word of art specifically relating to pederasty in which the pederast cultivates an emotional relationship with a child, usually in circumstances involving isolation and secrecy, so that sex may follow. “He was always plotting,” Edward Champion alleged, but it is difficult to see how Bailey could have been “plotting” in 1995, when his entire classroom was his theater for his pedagogical acting-out, to have sex with Eve Peyton in 2003, four years after she reached legal adulthood. He has denied forcing himself on any woman, including Valentina Rice in 2015. While it is impossible to know what actually happened with Valentina Rice, or with respect to the somewhat bizarre Old Dominion allegations, it seems a stretch to pin a charge of sexual assault onto someone whose alleged victims stay in touch with him for years afterwards.

Rather, Bailey was a walking argument against co-education for youngsters past puberty. He was the “cool teacher,” the schoolhouse equivalent of the “cool mom” played to perfection by Amy Poehler in Mean Girls: “Can I get you guys anything? Some snacks? A condom? Let me know.” Besides assigning his eighth-graders the usual cool-teacher reading list—Kurt Vonnegut, J.D. Salinger—Bailey, who was approaching or well into his 30s by then, liked to skateboard into class from time to time, and to sketch Beavis and Butthead on the blackboard. The Slate article reports: “He made his students feel like grown-ups: He cursed in front of them, told off-color jokes, and acknowledged the existence of sex. The teacher also wasn’t above acting like a teenager.” Some of this extended-adolescence mindset creeps occasionally into Bailey’s Roth biography, as when he flips off Joel Conarroe’s provision of female Penn students for Roth’s sexual delectation with “well, it was a different time to be sure.” (This aside and others of a similarly smirky vein made me curious about what the first drafts of all of Bailey’s books read like before an editor cleaned them up.)

Bailey had his eighth-graders keep journals for his regular inspection and commentary, which was unusually fulsome. Journaling can be an effective tool for helping writers loosen the flow of their prose and sharpen their perceptions of the world around them—but encouraging 13-year-olds to bare deeply “personal” reactions and feelings as Bailey explicitly did might have been expecting too much maturity from them, especially since Bailey sometimes shared their entries aloud with their classmates during class time. Many of his students aired their adolescent anxieties about their attractiveness to the opposite sex. Bailey, using drawings and doodles, was always reassuring. He encouraged boys to pursue their crushes on girls in the class, sometimes even dropping notes to the girls in question in order to jump-start the relationship. He told girls not to worry: Someday they’d grow up to be “beautiful.”

Paper assignments in his class often included relating a work of fiction they’d read—Slaughterhouse Five, for example—to traumas in their own lives. His students adored him, especially his female students, for whom he coined cute private nicknames in his journal comments. Eve Crawford Peyton was “Eveness.” Elisha Diamond was “Elishapoo.” He was always encouraging them to do more reading beyond his official class assignments. One of the books he recommended was Lolita. That novel is one of the English-language masterpieces of the 20th century—but was it really appropriate for a 13-year-old to be reading a book whose first sentence includes the phrase “fire of my loins” and whose plot revolves around the seduction of a 12-year-old girl by a middle-aged man?

No student at Lusher seemed to find any of this behavior odd at the time. They didn’t mind when Bailey showed up at a school dance to croon “Close to You” to some of the girls, or that he liked to watch them practice their modern dance in the school cafeteria while he had a cup of coffee. Those girls stayed in touch with Bailey through high school, sometimes in person, where they’d take—and save as keepsakes—photos of each other with an avuncular “Mr. Bailey” in the background wearing the Buddha smile that appears in many of his more recent portraits. More often, the continued contact was by handwritten letters and later email as the girls moved away to college and beyond. According to Eve Peyton in her Slate essay, Bailey in his correspondence “asked too many questions about our love lives, frequently inquiring if we’d ‘punched our V-cards yet,’ but we all still thought it was exciting to be treated like adults and talked to like adults.”

In some other world, such as that of the not-too-distant past, it would have been considered a gross violation of ethics and propriety for a teacher to eroticize explicitly a relationship that is already too prone to eroticization by female students overwhelmed by their teachers’ superior knowledge and charisma (I speak as someone who had a crush on nearly every one of my male college professors). Also in the not-too-distant past, any query from an adult man to an adolescent girl about her having “punched” her “V-card” would have resulted in a visit from her father with a baseball bat. But—at least in the somewhat speculative musings of blogger Edward Champion—there weren’t many fathers on the scene; Bailey’s favorite students, Champion asserted, tended to be “lonely girls who lived with single mothers.” According to Lusher administrators, there was not a single complaint on record about Bailey’s behavior during his entire eight years of teaching there. In 2000, just before he left, the nonprofit Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities awarded him its Humanities Teacher of the Year award (the endowment retroactively revoked the award this past May).

Bailey probably deserved to be a casualty of #MeToo more than some of its other victims. But he was also a casualty of the curious clash of #MeToo and its neo-fastidiousness about sexual exploitation with the no-holds-barred sexual revolution that had immediately preceded it. In this respect, the cool teacher who wanted to get down with his students at their sexual-blossoming level, only to discover a generation later that his coolness would be reclassified as rapey and their sexual blossoming as irrelevant, was actually an epigone of his biographical subject Philip Roth, who suffered his own descent from emblem of newfound ’60s sexual freedom with Portnoy to perennial feminist target of the 1990s and beyond.

III.

From the very beginning, Roth liked to think of himself as an agonist, tormented by, and tormentor of, a world of stifling conventional moralism, particularly regarding sexual matters. Specifically, it was the world of his childhood growing up in the hardworking, respectable lower-middle-class Jewish neighborhood of Weequahic in Newark, where divorces were scandal-fare and the teenage girls seemed unwilling to venture beyond necking (the Yiddish-derived aphorism “no chuppah, no shtuppah” apparently still had currency). After a session in Hebrew school, where he played the class smart-aleck, and his bar mitzvah at age 12, young Philip announced to his parents that that was the end of religious Judaism for him. Goodbye, Columbus, which catapulted him to fame at age 26, was a collection of satirical stories about the insular Jews of Newark and their middlebrow pretensions after they made some money and moved to the Jersey suburbs. After its publication, Roth painted himself as the put-upon victim of infuriated fellow Jews charging him with self-hatred—although in fact, as Judith Shulevitz pointed out in her Bailey review, when Roth famously appeared at a Yeshiva University symposium to defend the book in 1961, instead of being nearly driven out of the room by his angry co-religionists as was his story over the years (including to Bailey “a dazed man … surrounded by a scrum of detractors”), he was actually the “star of the evening,” greeted with general laughter and applause. (Shulevitz was quoting the Stanford historian Steven J. Zipperstein, who found a tape of the symposium; Zipperstein is currently working on his own Roth biography.)

Gentiles were also among Roth’s lifelong fixations as antagonists. He was ever on the alert for anti-Semitism, both real and imagined. He even classified Bloom, herself Jewish, as an anti-Semite; apparently, it was fine for Roth to rib his fellow Jews, but not Bloom. As an undergraduate at Bucknell University he found it “especially hateful” (Bailey’s words) that Bucknell during the 1950s required its students to attend weekly Christian chapel—leading me, at least, to wonder why, if that were so, Roth hadn’t picked a less sectarian institution of higher learning. In Roth’s fiction, gentiles are usually a curious mix of alcoholics, layabouts, thugs, wife-beaters, nymphomaniacs, genteel underachievers, and nascent Nazis: “goyish chaos,” as he called it. Roth had many gentile friends and many, many gentile lovers, but he insisted upon perpetually casting himself as the maligned and persecuted outsider.

Portnoy’s Complaint was perfectly timed; it hit the bookstores during the late 1960s just as prosperous postwar America decided to rebel against the perceived prudishness and hypocrisy of the traditional sexual order. As Adam Kirsch observed in a review of Bailey’s book for Tablet, Portnoy was the beneficiary of the fortuitous confluence of the sexual revolution and the Supreme Court’s nullification of state obscenity laws in the name of the First Amendment. Also, America’s mid-century receptiveness to Jewish humor (thanks most likely to television); the overbearing Jewish mother was already a staple in the joke repertoire of Milton Berle and Henny Youngman, while Lenny Bruce’s transgressive stand-up made wisecracking about hitherto-unmentionable topics such as masturbation seem fashionably anti-establishment. Freudian psychoanalysis, which attributed all neuroses to the repression of one’s sexuality, was also at its peak of fashionableness among those who could afford it during the late 1960s (this is a cultural trend that Bailey never discusses in his biography). Alexander Portnoy is on the couch in analysis writhing with guilt and anxiety, and so, in real life, was his creator. To top it off, Roth’s novel, although quite obscene, was screamingly funny. Portnoy’s Complaint provided readers with the thrill of seeing in print things once forbidden even to talk about, and it sold more than four million copies during its first five years in print. It also garnered high praise. In the New York Times, Christopher Lehmann-Haupt called it a “brilliantly vivid reading experience.”

Roth was indeed a brilliantly vivid writer, with a genius for recreating the human scene in sharp-eyed detail and with dialogue that uncannily mimicked heard speech. He could also write lyrically when he wanted to. He was not, however, as great a writer as he thought he was. As Shulevitz pointed out, he wrote a few great novels over the decades (his Pulitzer Prize-winning American Pastoral, published in 1997 and surprisingly sex scene-free, is likely among them), with the rest ranging “from good to terrible” in Shulevitz’s words. His admirable work ethic (inherited from his insurance-agent father) required him to spend eight hours a day every weekday writing, but the result was that he wrote much too much. The Human Stain (2000), about a distinguished professor, a black man who has renounced his ethnicity and passed for Jewish, only to be forced into retirement by accusations of racism over a chance remark in class, is a page-turner, but it has its longeurs—worked-over set pieces that go on and on, such as the 10 pages devoted to the disgraced professor’s three-decades-younger girlfriend’s dancing naked in front of him after the two have had sex. Roth never knew when to stop, and criticisms that he wrote the same novel over and over, and even the same passages over and over, were not unfounded.

Furthermore, he had trouble creating believable characters other than the many versions of himself—Alexander Portnoy, David Kepesh, the Roth-like writer Nathan Zuckerman (who shows up in nine Roth novels, including American Pastoral and The Human Stain), and even a pair of “Philip Roths”—whom he made his talky first-person narrators over the years. Lack of “roundness” isn’t just a problem with Roth’s female figures, but with all of them. They can be colorful enough—dazzling, Dickens-like sketches—but it is hard to believe that they could actually exist. To his Bard students of 1992, whom he characterized in his notes as saturated with “puritanical feminism,” Roth defended Sabbath’s Theater’s lascivious Drenka Balich with her English-as-a-second-language malapropisms, as “every bit as nasty/interesting” (Bailey’s phrase) as his male protagonist, Mickey Sabbath. But in fact Drenka, the self-described “sidekicker,” with a carnal appetite that defies realism, is yet another broadly drawn Roth cartoon.

In addition, as the story of the Yeshiva confrontation demonstrates, Roth dissembled constantly about himself. He maintained that his novels were not autobiographical, even though the publication of many of them was preceded by a visit to the libel lawyers to make sure they weren’t so á clef as to provoke a lawsuit. He worked virtuoso feats of imagination and low comedy on his material, but he invented almost nothing from whole cloth; his characters and their traits were stitched together, sometimes crudely, from bits and pieces of people he knew—or simply lifted with a change of name if he could get away with it, as with his first wife, Maggie, because legally you can’t defame the dead. A thinly fictionalized Maggie received exceptionally brutal treatment in at least two of his novels as well as in his 1988 autobiography, The Facts.

Among Roth’s other denials was that Sophie, the overbearing mother, and Jake, the long-suffering father, in Portnoy’s Complaint, were anything like his own loving parents, although his comically exaggerated portraits of the elder Portnoys were in fact not too far off the mark. In 2012, after reading a Wikipedia entry stating that The Human Stain had been based on the life of the critic Anatole Broyard, whose black (or, rather, mixed-race) identity had come to light only after his death in 1990, Roth wrote a 2,700-word “open letter” to the New Yorker asserting that he had met Broyard only three or four times and had completely made up the Human Stain plot, which he rehearsed in excruciating detail. In fact, Roth had known Broyard fairly well. He especially bristled when anyone referred to him as a Jewish writer: “I have never thought of myself [as such], for the length of a single sentence.” Of course, he wrote (through his numerous avatars) about nothing but being Jewish. In his Bard class he made a disparaging reference to Sholem Aleichem. The irony was that Roth, in countless fictionalizations, had turned his childhood neighborhood, Weequahic, into a cozy Fiddler on the Roof-style shtetl, to be escaped from but ever the object of nostalgia.

IV.

Roth’s problem for women wasn’t that he was misogynist as feminists charged; the laundry list of doting girlfriends (as well as close women friends including his favorite professor at Bucknell, Mildred Martin) should put paid to that allegation. His problem for women was that he was an alpha male. Starting at Weequahic High School (or even as a Hebrew school cut-up), he was the dominant personality in the circle of male friends that he always had around him. This continued throughout his life; indeed, one reason his first handpicked biographer, Ross Miller, fell out with him was that Miller viewed Roth as “surrounded by sycophants” (he was not the only one to make that observation). Roth’s worshippers included Joel Conarroe, pimping female students for him at Penn (Roth had befriended Connaroe after the latter wrote him a fan letter), and Alan Lelchuk, a younger writer whom Roth had met at the artists’ retreat Yaddo in the Adirondacks in 1969. Lelchuk was a Roth wannabe with whom Roth spent hours talking dirty and sharing the stacks of letters from female Portnoy readers who yearned to meet the author. Now a professor at Dartmouth, Lelchuk wrote some Portnoy-style fiction of his own during the 1970s, but he never achieved Roth-level success, and the friendship withered, especially after Roth lampooned him in one of his David Kepesh novels, The Professor of Desire (1977). Blake Bailey would seem to have been yet another addition to the Roth buddy hierarchy. One of the most peculiar but perhaps telling passages in Philip Roth: The Biography is a description of the two hearing “each other’s muffled streams” during bathroom breaks in interviews at Roth’s Connecticut house in 2012. “One lovely sun-dappled afternoon,” Bailey writes, “I sat on his studio couch, listening to our greatest living novelist empty his bladder, and reflected that this was about as good as it gets for an American literary biographer.” Well, yeah, if you say so.

As for the girlfriends, the photo album full of them and more, I asked my husband why a man would feel compelled to have sex with quite so many different women. He answered, “Women have no idea how attractive they are to men.” Roth slept with dozens of women because he could. There were no constraints for him—not moral precepts, not marriage vows, not love or loyalty—so he followed his desire where it led him. After Felicity, the friend of Claire Bloom’s daughter, Anna Steiger, turned down his advances, he taunted her (according to Steiger): “What’s the point of having a pretty girl in the house if you don’t fuck her?” As Bailey writes, “[H]is impulse to mock a certain kind of bourgeois piety was among his most pronounced traits, both as a writer and as a man.” The sexual revolution said chastity and fidelity were bourgeois pieties, so that was that. “America’s greatest living writer” said the rest. And while the elderly Roth, straggling locks framing a domelike bald head, looked like a bird of prey, when he was younger, he cut a raffish figure, at least in photos, with a taste for haberdashery. What was there to resist? Of course there was a compulsive aspect to Roth’s sexuality that one would rather not think about too much. Inga Larsen told Bailey that she had to feign more delight than she actually felt when Roth handed her a semen-encrusted napkin or would call her at work and masturbate over the telephone. Spilled semen occupies a disturbingly large space in quite a few of Roth’s novels besides Portnoy.

As the 1990s came and went, and certainly during the years before his death when the #MeToo movement was gathering steam, Roth’s hostility toward feminist censoriousness turned into active alarm. He worried that Felicity might accuse him of having done something more than making a pass on the stairway and acting obnoxious afterwards. He was especially distraught by Inga Larsen’s revelations in interviews with Bailey for the biography. While her fictional counterpart, Drenka Balich, might have died romantically (and conveniently for her creator), Roth dumped Inga in 1995 after she refused his demand that she not tell her children where she would be on a trip abroad the two had planned (the secrecy of their relationship had been an erotic frisson for him). She checked into a mental hospital—and she was not the first of Roth’s exes to contemplate and even attempt suicide. In his last press interview, with Charles McGrath of the New York Times in January 2018, four months before his death, Roth seemed agitated that readers might confuse his fictional protagonists’ priapism with any attitudes of his own that might provoke #MeToo associations. “I have imagined,” he declared, “a small coterie of unsettled men possessed by just such inflammatory forces they must negotiate and contend with.” The emphasis was on the “imagined.” It was an emphasis that appeared disingenuous to many New York Times readers by 2018, Bailey reports.

Sabbath’s Theater, ironically making its publication debut only a few months after the model for its gleefully deliquescent “sidekicker” heroine had thought about killing herself, is perhaps a tell. It was Roth’s favorite among his novels, and he maintained that the aged, porcine, grotesquely repulsive, and promiscuous failed puppeteer Mickey Sabbath was “the nearest I’ve come in all my fiction to drawing a realistic self-portrait.” The reviews, from distinguished literary critics, reflected what might be seen as the last gasp of 1960s revelry in newfound sexual freedom. “[H]ilariously serious about life and death” was the pronouncement of Frank Kermode in the New York Review of Books. William Pritchard, writing for the New York Times, called the novel “funny and profound.”

But it is hard to discern exactly what is supposed to be so “funny” and so “hilarious” about the 60-something Sabbath’s public humiliation of his mistress’s cuckolded husband, his mockery of his wife’s psychological breakdown, and his repayment of the hospitality of his sole remaining friend by stealing his money, setting up an assignation with his wife, and masturbating into the underpants of his college-student daughter. This is a far cry, as Michiko Kakutani wrote in a rare dissenting critique in the New York Times, from Portnoy’s Complaint and its protagonist’s “attacks of conscience coupled with his rage to revolt [that] gave that novel an exuberant comic energy.” Personally, I found Sabbath’s Theater nearly unreadable. I couldn’t get through more than a few lines of its tour de force: a 20-page footnote stuck into the middle of the book that purports to be the transcript of Sabbath’s secretly taped half-hour of phone sex between himself and a female student in his college puppet-making class who is 45 years his junior (“What are you doing right now?…”). I suppose there is something “profound” and “serious about life and death” in all of this, something about King Lear or Prospero (“every third thought shall be my grave”) or Sabbath’s kind and virtuous older brother having been killed in World War II. I just wanted someone to shoot Sabbath in the face so he could burn in hell and the book could end.

The feminists who rang down the curtain on this sort of once-fashionable outrageousness (in the novel, Sabbath, who has surreptitiously made dozens of tapes recording his students, gets outed by a group calling itself Women Against Sexual Abuse, Belittlement, Battering, and Telephone Harassment) had a point. Here is Sabbath reflecting: “[T]here was in these tapes a kind of art in the way he was able to unshackle his girls from their habit of innocence.” This is a chilling sentence. The traditional restrictions on unbridled sexual expression that the 1960s overturned might have been overly restrictive, but they recognized that the sexual urge wasn’t simply a healthy force that required an outlet—it was something potentially uncontrollable and dangerous, all too amenable to the overpowering of the weak by the strong. The strong usually means men, not only because they are physically more powerful, but also because they are more pointedly, more insistently aggressive.

This is not to say that women don’t have their own sexual thirsts and susceptibilities; we are all daughters of Eve and cousins of Emma Bovary. But it is amazing how readily libido shades into libido dominandi. Not surprisingly, after the old restrictions fell, feminism quickly erected new restrictions with their own vocabulary that Roth railed against as so much cant: “rape culture,” “emotional abuse,” “harassment,” “power imbalance,” and the rest of the #MeToo lectionary. Yet Roth could see very clearly, in his self-recognition in Sabbath’s Theater, the very dark side of his own male nature, his human nature, his “human stain”—and it is to his credit as a writer that he did so. In Roth’s fiction, it began as early as Goodbye, Columbus, in which the Roth stand-in, Neil Klugman, strong-arms Brenda Patimkin into getting a diaphragm (a task that entailed some effort for an unmarried woman back then) so that he can enjoy the sex with more peace of mind.

Blake Bailey, before his fall, insisted in interviews that he had not, as Laura Marsh and Judith Shulevitz charged, complacently accepted Roth’s version of Roth’s love life—although one might wonder about Bailey’s description of Felicity’s unwillingness to partner in quasi-adultery with her best friend’s quasi-stepfather under the roof of her best friend’s mother as “a certain kind of bourgeois piety.” But perhaps we will never know. In an April 2nd interview with Vulture, Bailey bragged: “No biographer will ever have access to the living man again. All his private papers are under public seal until 2050. … So I’m just stating a fact that my book, whether you like it or not, will be hard to replicate in its definitiveness.”

This is an unfortunate prospect. There is the matter of Roth’s two marriages, which in Bailey’s biography, as well as in Roth’s numerous fictional and nonfictional efforts to control the narrative, consisted of the unwitting author’s having been trapped into wedlock by monstrously dysfunctional but preternaturally cunning harridans. Claire Bloom could take care of herself—and did, in a bestselling tell-all 1996 memoir, Leaving a Doll’s House, that left Roth rattled until the end of his days. Maggie, the first wife killed in the 1968 auto accident, was not so lucky. The centerpiece of Bailey’s Roth-channeling storytelling is that Maggie, in order to trick Roth into marrying her, paid a destitute pregnant black woman to supply her urine for a drugstore pregnancy test; if the test was positive, Maggie would get an abortion, which she allegedly faked as well, going off to a movie, or maybe a Turkish bath, instead. This uncorroborated tale is so outlandish—Maggie had two other real abortions, before and after the wedding, each personally supervised by Roth—that the only evidence for its believability is that Roth signed an affidavit to that effect in the couple’s divorce proceedings. With Bailey, well, it’s the “urine ruse” and the “urine fraud” over and over.

Bailey quotes here and there from a journal that Maggie seemed to have kept in a blue spiral notebook to which he had access through Roth (Roth also reproduced parts of the journal in his Maggie-dishing 1974 novel, My Life As a Man). Bailey, in a bit of Lusher cool-teacher rhetoric, dismisses the journal in a footnote as “a pretty insipid piece of writing.” But the journal—clearly one of Roth’s most significant life-records—appears nowhere in Bailey’s extensive apparatus, and it remains a mystery as to where it actually resides right now. Is it part of a massive personal archive that Roth turned over to the Library of Congress before he died—or is it part of those Roth materials that no one besides Bailey will see until 2050? (Bailey says in an endnote on page 826 that Roth “gave” him the journal, so it may well be in Bailey’s own possession.) Maggie, whom Bailey describes as a “sexually undesirable divorcée” (thanks!), was with Roth for seven years, longer than any woman except Bloom and Inga Larsen, but she is a completely incoherent figure in Philip Roth: The Biography, where Bailey presents her simply as a nagging, troubled, downmarket obstacle to Roth’s burgeoning writerly career. Perhaps Steven Zipperstein will be able to track down that journal. I certainly hope so.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this essay misidentified Dwight Garner as the LA Times book critic. Apologies for the error.