American History

Making America British Again

The story of William Cobbett and the American Revolutionary culture wars.

“Everything,” wrote the historian A.T.Q. Stewart, “is older than you think it is.” There is a striking similarity between the mindsets of late eighteenth-century American radicals and the progressive radicals of today. Both groups exhibit a sense of absolute moral certainty, and both want to remake the world based on what they see as principles that no reasonable person could oppose. Who, after all, could possibly disagree that diversity, equity, and inclusion are good things—or that liberty, equality, and fraternity should form the basis of a just society? Only the privileged or ignorant—and the privileged need to be overthrown and the ignorant re-educated.

History is full of examples of where that kind of thinking can lead. Context is crucial. During the French Revolution, against the background of terror and total war, then US Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson admonished his chargé d’affaires in Paris for being too critical of the revolutionaries:

The liberty of the whole earth was depending on the contest. Rather than it should have failed, I would have seen half the earth desolated. Were there but an Adam and Eve left in every country, and left free, it would be better than as now it is.

As Conor Cruise O’Brien has pointed out, this is the language of Pol Pot. Jefferson was not alone in his view that massive loss of life was an acceptable price to pay in the quest for liberty. When the Irish revolutionary Wolfe Tone arrived in Philadelphia, he didn’t much like the living, breathing Americans he met; they were, he wrote, “a disgusting race, eaten up with all the vile of commerce.” But he loved their system of government, which brought “Affluence and ease” to all US citizens. “These are the things,” he argues, “for which the lives of Thousands and Tens of Thousands are a cheap purchase.” The English radical Joseph Priestley, who emigrated to the US after his chemical laboratory was destroyed by a Church-and-King crowd, thought along the same lines. By 1798, he feared that the struggle between supporters and opponents of the French Revolution had brought the country to the brink of civil war, but he was confident that the forces of “luxury, vice, and folly” would be defeated:

Many lives, no doubt, will be lost in war, civil or foreign, but men must die; and if the destruction of one generation be the means of producing another which shall be wiser and better, the good will exceed the evil, great as it may be, and greatly to be deplored, as all evils ought to be.

This was exactly this kind of thinking that Edmund Burke decries in his Reflections on the Revolution in France. In a letter of March 1790, written while he was completing that book, he wrote:

I have no great opinion of that sublime abstract, metaphysic reversionary, contingent humanity, which in cold blood can subject the present time, and those whom we daily see and converse with, to immediate calamities in favour of the future and uncertain benefit of persons who only exist in idea. [Emphases in the original.]

But for the revolutionaries, the imagined future exerted a powerful hold on the present. To many American commentators, the stakes seemed very high indeed—nothing less than the survival of their own new nation. Among the strongest supporters of the French Revolution were the Democratic Societies that emerged in 1793 to protect the United States from international counter-revolution and internal “monarchical” and “aristocratic” tendencies. Attracting considerable support from the American middle classes, they stood for universal male suffrage, economic liberty, and a broadly egalitarian society. Embracing the styles and slogans of revolutionary France, they greeted each other as “citizens,” wore liberty caps and cockades, attended civic feasts celebrating the triumphs of French armies over the “leagued despots” of Europe and injected a spirit of secular millenarianism into American politics. In imitation of the French revolutionary calendar, in which 1792 became Year I of the Republic, the Philadelphia Democratic Society dated its resolutions from America’s own Year I, 1776; thus, 1794 became the Eighteenth Year of American Independence. This reflected their belief that the American and French revolutions would together sweep away the accumulated rubbish of ages and begin the world over again.

Radical politics began to permeate the eighteenth-century equivalents of social media: broadsides, pamphlets, newspapers, plays, street theatre, and songs. Language itself was to be revolutionised. In a prize-winning essay delivered at the American Philosophical Society in 1793, William Thornton insisted that Americans shake off English linguistic imperialism by abolishing the existing alphabet and replacing it with a rational system based on the phonetics of liberty:

You have already taught a race of men to reject the imposition of tyranny, and have set a brilliant example, which all will follow, when reason has assumed her sway. You have corrected the dangerous doctrines of European powers, correct now the languages you have imported, for the oppressed of various nations knock at your gates to be received as your brethren…. The AMERICAN LANGUAGE will thus be as distinct as the government, free from all the follies of unphilosophical fashion, and resting upon truth as its only regulator.

Noah Webster’s new dictionary of 1806 bears traces of this spirit. To spell plough “plow” or to omit the silent “u” from words like “honor” and “labor” was a declaration of American independence from Old World obscurantism.

Gender relations were also to be revolutionised. The word “citizen” and its feminine form, “citess,” were to replace traditional honorifics such as Mr, Mrs, and Miss. A January 1790 article in the Philadelphia Aurora, edited by Benjamin Franklin’s grandson Benjamin Franklin Bache, complains that women have been written out of history and calls upon them to claim full civil, political, and social equality with men, anticipating Mary Wollstonecraft’s arguments in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792). In the epilogue to her 1794 play Slaves in Algiers, or A Struggle for Freedom, Susanna Rowson tells her audience: “Women were born for universal sway,/Men to adore, be silent and obey.” The play, it should be noted, is not about black slavery—about which many radicals were conflicted—but rather about white slaves attempting to escape to the Land of Liberty. In 1798, the play Female Patriotism, written by John Daly Burk, reinvented Joan of Arc as a French revolutionary heroine bringing liberty and equality to a benighted world—though at the end of the play, once her victory against the English has been assured, she returns to a life of domestic bliss. Female patriotism clearly had its limits.

The spirit of revolution and the celebration of revolutionary violence also pervaded street theatre and popular songs. An effigy of Louis XVI was guillotined twenty to thirty times a day in a popular show of 1793. The following year, John Jay’s effigy was guillotined up and down the eastern seaboard after he signed a treaty of rapprochement with Great Britain. Meanwhile, Joel Barlow decided to rewrite Britain’s national anthem:

God Save the Guillotine

’Till England’s King and Queen,

Her power shall prove:

’Till each anointed knob

Affords a clipping job,

Let no vile halter rob,

The Guillotine.

Not to be outdone, the Democratic Society of Philadelphia included among its toasts “The Guillotine to all Tyrants, Plunderers and funding Speculators.”

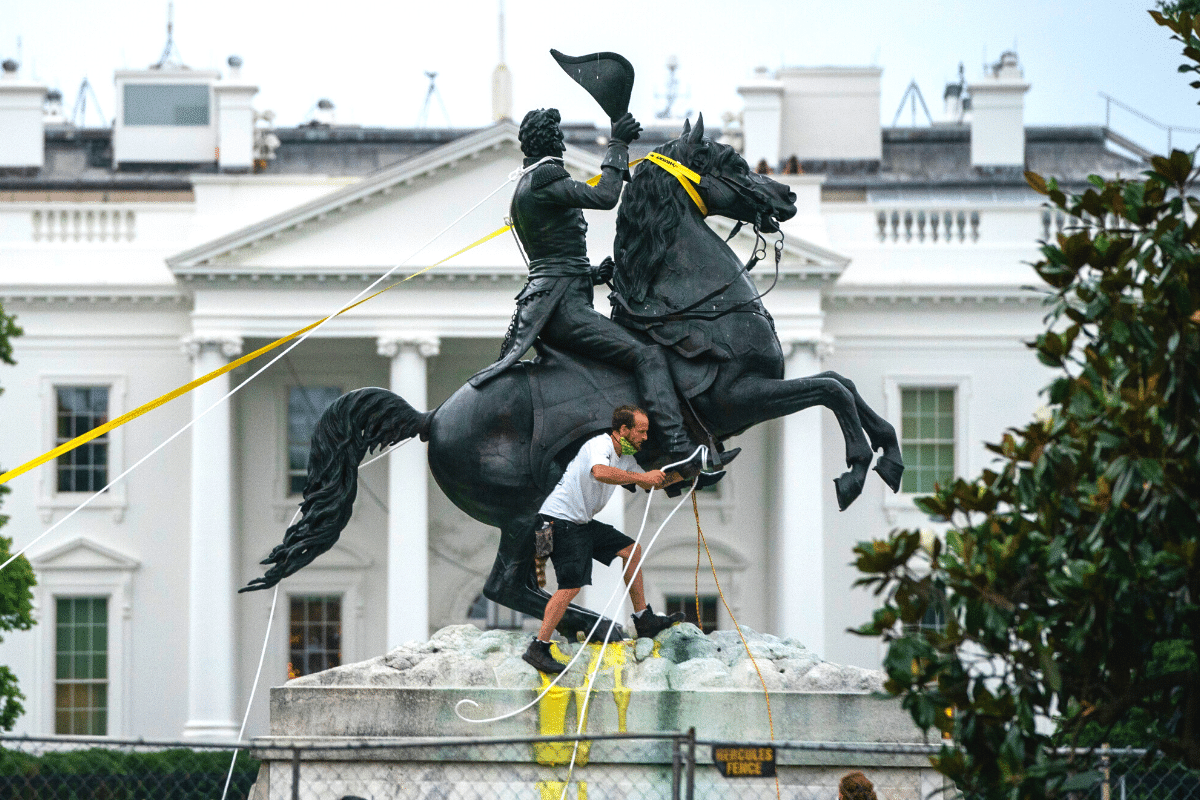

In Charleston, a statue of Lord Chatham was pulled over and decapitated; in Christ Church, Philadelphia, a bust of George II was shattered. In New York, Queen Street became Pearl Street, while King Street became Liberty Street; in Boston, the Royal Exchange Alley became Equality Lane. In schools and universities, education became increasingly politicised; republican principles were being written on the supposedly blank slates of young minds. At the University of Philadelphia, a teacher decided to improve upon Shakespeare by rewriting the peroration of Henry V’s speech at the siege of Harfleur: the original words “Follow your spirit, and, upon this charge, Cry—God for Harry! England! and St. George!” now became “Follow your spirit, and, upon this charge, Cry—God for Freedom! France! and Robespierre!”