Art and Culture

Abiding Legends

Richard Matheson, George R. Stewart, and the birth of the Calipocalypse.

I.

The end of the world is back in vogue. A number of publications—including this one—have recently examined the possibility that World War III might be at hand. Literary speculation about the end of mankind dates back, at least, to the story of Noah and the Ark. Mary Shelley, famous for her 1818 novel Frankenstein, rekindled interest in end-of-mankind narratives with her second novel, The Last Man. Published in 1826, it tells the story of a pandemic that kills almost every human being on earth. Though the novel wasn’t immediately successful, it later became the inspiration for much of what we now call apocalyptic fiction, a genre that became enormously popular after the advent of the atomic bomb.

British journalist Dorian Lynskey’s new book, Everything Must Go: The Stories We Tell About the End of the World, recounts not only the birth of Shelley’s The Last Man but also many of its offspring. Two of the most influential American novels Lynskey discusses are celebrating significant birthdays this year. George R. Stewart’s Earth Abides—first published on 24 October 1949—turns 75 this year, and Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend—first published on 7 August 1954—turns 70. It’s probably not a coincidence that many of the best American apocalypse stories come out of California. Goodreads has a list of 76 Calipocalypse tales and it is far from complete (I Am Legend isn’t even on the list).

With its reputation for earthquakes and wildfires and Pacific storms, the Golden State is an ideal location for all sorts of disaster stories. It also hosts more than thirty military bases, a number of major defence contractors, and numerous research facilities, including the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, where a great deal of nuclear-weapons research took place after WWII. The fact that California draws a huge number of foreign tourists also makes it a likely spot for a foreign virus to reach American shores.

New York City, where residents mostly live in dense multi-family housing, doesn’t provide the same kind of eerie, unpopulated suburban landscapes. Without any traffic, you could drive from one end of Manhattan to the other in a few minutes. But both Stewart’s Earth Abides and Matheson’s I Am Legend linger over California’s rolling hills and endless rows of suburban houses left empty by mysterious pandemics.

II.

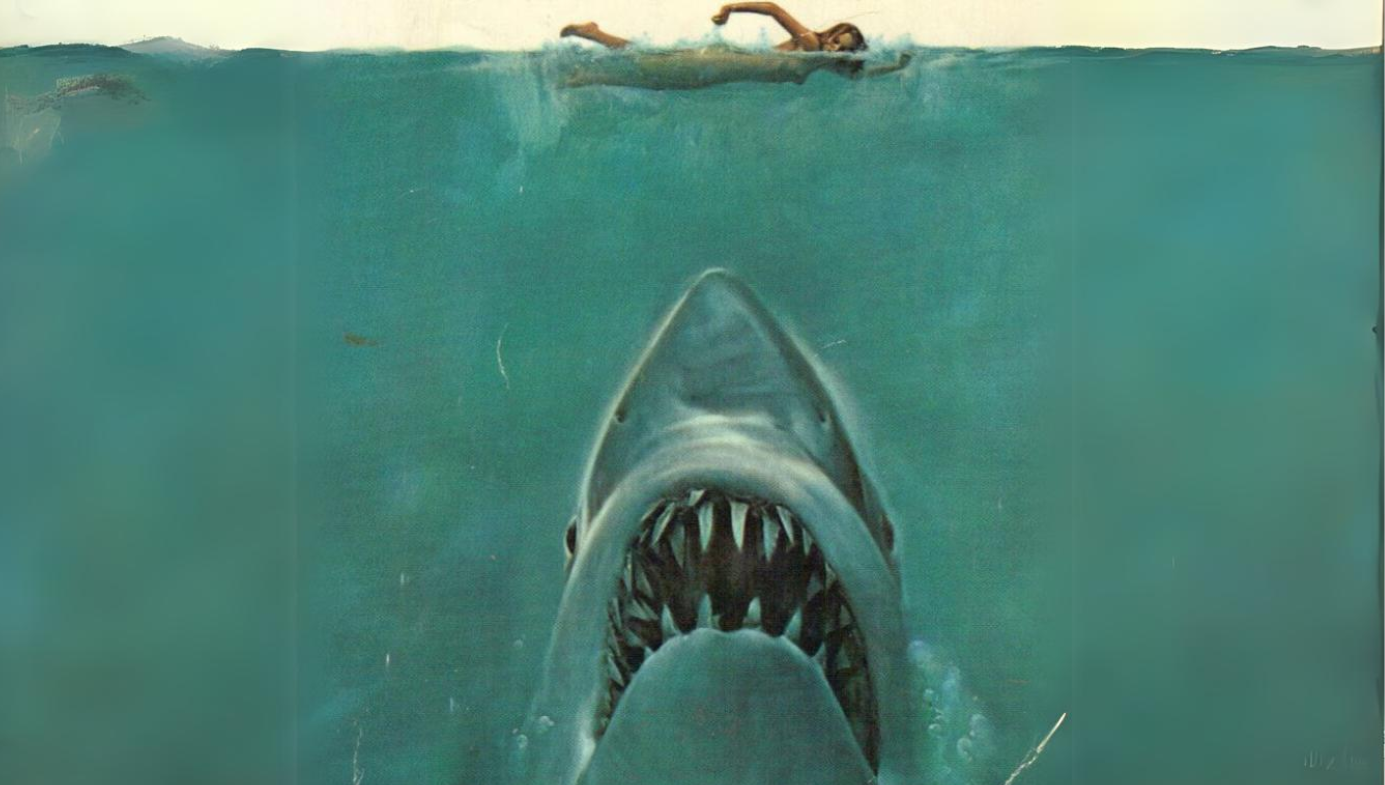

Nowadays, Matheson’s novel is probably the better known of the two, primarily as a result of its three film adaptations: 1964’s The Last Man on Earth starring Vincent Price (the title of which directly references Shelley’s influence), 1971’s The Omega Man starring Charlton Heston (the title of which indirectly references Shelley’s influence), and 2007’s I Am Legend starring Will Smith. In Everything Must Go, Dorian Lynskey writes, “The book that really made the last man a going concern in popular fiction was Richard Matheson’s hugely influential 1954 novel I Am Legend.”

Matheson’s innovation was to turn the plot of Shelley’s The Last Man into a modern zombie novel, a subgenre that hadn’t even been invented back in 1954. Zombies originated in Haitian folklore, but they didn’t become a mainstay of popular fiction in English until fairly recently. When Matheson brought them to life in I Am Legend, he didn’t have a name for them, so he called his monsters vampires. But Matheson’s creatures didn’t fit the familiar description of vampires. They crouched on their haunches, ground their teeth back and forth, and moved very slowly, howling rather than speaking. Discussing the inspiration for his 1968 zombie classic Night of the Living Dead, George A. Romero later acknowledged, “I had written a short story, which I basically had ripped off from a Richard Matheson novel called I Am Legend.”

Matheson’s novel takes place in Los Angeles, shortly after a world war has wiped out most of earth’s population and unleashed a pandemic that has turned every survivor but protagonist Robert Neville into a flesh-eating corpse. Neville lives in a house on Cimarron Street in LA and keeps his doors and windows boarded up whenever he is home. He still has a working refrigerator and some other appliances thanks to a gas-powered generator he keeps in the garage, and he leaves the house only by day, mostly to collect supplies from ransacked hardware and grocery stores. While he is out, he kills any sleeping vampires he encounters. At night, the vampires return the favour by slouching towards Cimarron to try to kill Neville.

“With the notable exceptions of Mary Shelley and Richard Matheson,” Dorian Lynskey writes, “almost every last-man story retreats from the premise sooner or later. It seems that we find it easy to imagine the end of the world but not going through it alone.” Screenwriter and director David Koepp agrees. In 2022, he told an interviewer, “The book I can’t stop thinking about? Probably ‘I Am Legend,’ by the late, great Richard Matheson, one of my other favorite authors of all time. FOUR TIMES Hollywood took a crack at that story, and they STILL haven’t used Matheson’s ending, which is just utterly brilliant and devastating. The title of the book makes no sense without Matheson’s original ending!”

Matheson was a young married man with children when he wrote I Am Legend. His early years as a writer were tough. As he explained to an interviewer, “My theme in those years was of a man, isolated and alone, and assaulted on all sides by everything you could imagine.” I Am Legend was published the same year as Jack Finney’s The Body Snatchers, another Calipocalypse tale and the source of Don Siegel’s 1956 film Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Both novels are about the transformation of human beings into soulless vessels.

Some early commentators thought the pod people in Body Snatchers and zombies in I Am Legend were meant to represent the sneaking threat of communism or subversive atheism. Others thought the empty men represented the dehumanising conformity of the American suburban dweller. Both books, like almost all worthwhile art, invite a variety of interpretations. A recent academic study of I Am Legend published in Advances in Literary Study sees it as an attack upon wokeness and “a metaphor for the sociopolitical collapse of patriarchal hegemony.”

Considering how influential it became, it may surprise some people to learn that I Am Legend wasn’t a critical success at the time of its publication. Damon Knight, a prominent sci-fi writer and critic and editor, wrote of I Am Legend:

The book is full of good ideas, every other one of which is immediately dropped and kicked out of sight. The characters are child’s drawings, as blank-eyed and expressionless as the author himself in his back-cover photograph. The plot limps. All the same, the story could have been an admirable minor work in the tradition of Dracula, if only the author, or somebody, had not insisted on encumbering it with the year’s most childish set of “scientific” rationalizations.

In the sci-fi magazine Galaxy, another critic noted that the book was “a weird [and] rather slow-moving first novel … a horrid, violent, sometimes exciting but too often overdone tour de force.” (I Am Legend was Matheson’s third published novel, not his first.)

Some of these criticisms are fair, although they are largely beside the point. I Am Legend is not an elegant or shapely novel, and Matheson wasn’t a great prose stylist. But he doesn’t seem to have aspired to write long, eloquent novels exploring every aspect of, say, existential loneliness. He was an ideas man with a particular gift for the clever fictional conceit, which is why his work has been so successful on screens both big (The Incredible Shrinking Man, Somewhere in Time, Stir of Echoes) and small (The Twilight Zone).

We learn nothing about the murderous driver of the truck and very little about his quarry in Steven Spielberg’s debut feature Duel, which was produced from a script by Matheson (based on his own story, published in Playboy). But that anonymity is part of what gives the film its peculiar power. Dennis Weaver’s everyman hasn’t done anything wrong, but for some reason, the unseen driver of a monstrous truck is trying to kill him. Similarly, part of what makes I Am Legend such a powerful novel is Matheson’s elision of much of the information we need to fully understand the world he has created.

I Am Legend is a short novel. My vintage paperback edition runs to 174 pages (Charlton Heston read the whole thing during a flight, which convinced him it would be a good movie; he was apparently unaware that it had already been filmed at least once). Dorian Lynskey doesn’t care much for either the 1964 film adaptation, The Last Man on Earth, or 1971’s The Omega Man. He calls the former “glum and inert” and the latter “tonally chaotic.”

In his nonfiction book about the horror genre, Danse Macabre, Stephen King dismissed The Omega Man (“[T]he vampires become almost cartoon Gestapo agents in their black clothes and their sunglasses”), but he praised The Last Man on Earth:

This film is more faithful to Matheson’s novel, and as a result it offers a subtext which tells us that politics themselves are not immutable, that times change, and that Neville’s very success as a vampire-hunter … has turned him into the monster, the outlaw, the Gestapo agent who strikes at the helpless as they sleep.

King called it “the ultimate political horror film” and argued that it resonated in a country shocked by events like the My Lai Massacre and the Kent State shootings (both of which occurred a few years after the film was made). He probably credited The Last Man on Earth with more political savvy than it actually deserves. Nevertheless, the film is a good one, and I’m fond of The Omega Man as well.

III.

Five years before Matheson released his vampires into LA, George R. Stewart unleashed a plague that killed almost everyone on the planet in his novel Earth Abides. Stewart was a better writer than Matheson, and the prose in Earth Abides is crisp and smart. Alas, Stewart lacked Matheson’s ability to produce clever plot twists, so his novel isn’t always as compelling as I Am Legend. It often resembles a leisurely stroll through the blasted heath of a largely depopulated America. Nonetheless, it is beautifully done and hugely influential.

The first great American post-apocalypse novel of the post-WWII era, it kicked off a vogue for the genre that would soon produce iconic titles like A Canticle for Liebowitz, Fail-Safe, On the Beach, and The Stand (Stephen King has called Earth Abides a major influence on his novel). Cormac McCarthy’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 2006 novel, The Road, is also a direct descendent, as are Emily St. John Mandel’s 2014 novel Station Eleven and P.D. James’s 1992 novel, The Children of Men. Ray Bradbury’s Calipocalypse short story “There Will Come Soft Rains” was published just six months after Earth Abides and may well have been inspired by it. And of course, there was I Am Legend.

Stewart was born in Sewickly, Pennsylvania, in 1895, and grew up in Indiana, Pennsylvania, the hometown of actor James Stewart (who was no relation). His early life was often affected by sickness and infectious disease. In 1906, his five-year-old brother contracted typhoid fever and died. Stewart himself nearly died during the Great Spanish Influenza pandemic of 1918 that killed 20 million people worldwide, including 600,000 Americans. Stewart survived, but suffered from lung problems for the rest of his life. His father moved the family to Southern California in 1908 after his own bout with pneumonia forced him to seek a warmer climate. Stewart’s daughter, Jill, had a tuberculosis scare when she was a child. All of which might explain why he found pandemics so fascinating.

Stewart’s boyhood in Los Angeles County brought him into contact with a number of future cultural icons. He became best friends with a boy named Buddy DeSylva, who would go on to write or co-write a number of popular songs, including “April Showers,” “The Best Things In Life Are Free,” “Button Up Your Overcoat,” “The Birth of the Blues,” and “California, Here I Come.” Stewart attended Pasadena High School with future film director Howard Hawks. He once played tennis against future Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Thornton Wilder. Later, at Princeton, he participated in a relay race with F. Scott Fitzgerald. Throughout his life, Stewart had an almost Zelig-like ability to find himself connected, if only tangentially, to prominent people.

As an adult, Stewart became a renowned scholar, an English professor at the University of California at Berkeley fascinated by history, geography, and American landscapes, in particular. He was also a prolific writer, and Earth Abides wasn’t the only one of his books to gain popularity. Stewart’s Wikipedia entry tells us that “his work was not known well during his lifetime, and is now almost forgotten.” Neither of those statements is true. If he never became a brand-name author, it’s because he wasn’t interested in self-promotion. He preferred to spend his time reading, writing, researching, and teaching. But he had a very successful career.

Like Richard Matheson, Charles Portis (True Grit), Walter Tevis (The Hustler), John Ball (In the Heat of the Night), Jack Finney (The Body Snatchers), Richard Condon (The Manchurian Candidate), and many others, Stewart’s books were far more famous than his name. His harrowing 1936 nonfiction work, Ordeal By Hunger: The Story of the Donner Party, was a huge success, both critically and commercially. Twenty-four years later, in an introduction to the updated 1960 edition, Stewart noted that the book “has been read by thousands of people [and] has already begun to achieve a kind of classic quality.” By making the landscape of Northern California’s Sierra Mountains what he described as “one of the chief characters of the tale,” Stewart became one of the first progenitors of the contemporary environmental narrative, which he would further explore with several subsequent novels, including Storm (1941) and Fire (1948).

Walt Disney was so impressed by the way Stewart wrote about America that, in the late 1940s, he invited the author to spend a week at the Disney Studios in Los Angeles. Disney wanted to create a series of films about small-town America, and he asked Stewart to pitch him some ideas (the films were never made). “Disney clearly knew Stewart’s work,” Stewart’s biographer, Donald M. Scott, writes in The Life and Truth of George R. Stewart, “and … Stewart’s ideas about American folklore would have been of great interest to Walt Disney as he thought about the Disneylandia project.”

Storm has been republished numerous times over the last eight decades, and it is currently part of the New York Review of Books Classics series. Its success even helped to popularise the now-commonplace practice of giving (usually feminine) names to tropical storms (although nowadays, the names are just as often masculine). A meteorologist in the book christens the titular weather event “Maria” (pronounced ma-RYE-uh, according to a note by Stewart), which inspired the songwriting team of Alan J. Lerner and Frederick Loewe to write a song titled “They Call the Wind Maria” for their 1951 Broadway musical Paint Your Wagon.

In 1959, the novel was adapted as an episode of ABC’s Walt Disney Presents TV series and given the title “A Storm Called Maria.” In 1948, Stewart wrote a sequel called Fire, the main character of which is a California wildfire (nicknamed “Spitcat”) that rages out of control. Walt Disney Presents adapted that for TV, too. Fire was republished many times through the years and a new edition will be released as part of the NYRB Classics series on 13 August.

Stewart’s 1945 nonfiction book, Names on the Land, has also been reprinted as an NYRB Classic, and it inspired some of its readers to take an interest in place names. In the late 1940s, the Mutual Broadcasting System had a popular radio mystery program called The Casebook of Gregory Hood. The 26 August 1946 episode was called “The Ghost Town Mortuary” and it was set in Berkeley. It featured this exchange of (rather clunky) dialogue between the main characters:

GREGORY: This place is handy for the one person I think can help us on this case.

SANDY: And who is that person?

GREGORY: Professor George Stewart of the University English Department.

MARY: Oh yes! He wrote Storm. A wonderful book.

GREGORY: True, but what is more to our immediate point is the fact that Random House recently published his new book Names on the Land. It’s a classic and definitive study of American place-naming. His virtues are many, including a fine sense of entering on cue. Hello, George.

STEWART: I got your message, Greg, and it all sounds frightfully mysterious. What’s your problem?

Gregory Hood, a private eye, explains that he is looking for a missing woman. Before she disappeared, she dashed off a telegram that contained a single word: Difficult. Hood asks Stewart if this could be a reference to a town of some sort. Stewart explains that there is an American town called Difficult. Apparently, when the town’s founding fathers filed its name with the US Postal Service, the Service responded with a message that read, “THE NAME OF YOUR TOWN IS DIFFICULT.” And so, that became the town’s name. George R. Stewart, with his vast knowledge of American place names, solved the mystery.

As a teacher, Stewart shaped the minds of many students who would also grow up to be influential. In the 1930s, an aspiring writer and UC Berkeley student named Robert Galen Fogerty took every class he could from Stewart. According to Donald Scott, “Fogerty believed Stewart had a great influence on his life and character—and on the music of the 1960s group Creedence Clearwater Revival, since Creedence founders Tom and John Fogerty were Robert Fogerty’s sons.” Few rock bands explored American folklore as thoroughly as CCR. The lyrics of at least three CCR songs—“Have You Ever Seen the Rain?” “Who’ll Stop the Rain?” and “Bad Moon Rising”—sound like they might have been influenced by Storm. In a single (abbreviated) sentence from that novel, you’ll find material that could have inspired three different CCR songs: “Against all the cities of the plain the storm was beating … Lodi of the grapes … Porterville of the oranges; Tulare of the cotton.”

Bestselling books, Broadway musicals, national radio broadcasts, Berkeley lecture halls, Disney TV movies, Ray Bradbury short stories, CCR songs—Stewart’s influence seemed to be everywhere in mid-20th-century America. Whoever wrote that line in Stewart’s Wikipedia entry simply wasn’t paying attention. Signed copies of his novels are listed for sale at the American Book Exchange for as much as $4,750. Works by forgotten authors rarely fetch prices that high.

IV.

Stewart’s most popular novel was Earth Abides, which won the very first International Fantasy Award back in 1951. An impressive accomplishment when you consider that it was published in the same year as George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (originally titled The Last Man in Europe). It has appeared on numerous lists of the best science-fiction novels of all time, generally near the very top.

The book had a profound influence on Stephen King and numerous other creative artists as well. Carl Sandberg thought it was one of the greatest books of its time, as did Wallace Stegner. It was Jimi Hendrix’s favourite book and inspired his song “Third Stone from the Sun.” In a glowing introduction to Walter Tevis’s 1980 apocalypse novel, Mockingbird, Jonathan Lethem writes, “Chunks of books like 1984 and Brave New World and Earth Abides seem to be swallowed here, likely because Tevis knew those books…” Like Earth Abides, Philip K. Dick’s 1965 Calipocalypse Dr. Bloodmoney mostly takes place in and around Berkeley after a nuclear catastrophe has knocked much of humankind back into a pre-modern era of technology. Dick’s book was almost certainly influenced by Stewart’s.

David Koepp has written two brilliant near-apocalypse novels, 2019’s Cold Storage, about an earth-threatening fungus, and 2022’s Aurora, about an earth-threatening solar storm. Asked by Crime Reads to list “Seven Essential Contagion Novels,” Koepp put Earth Abides in second place on his list, right below The Andromeda Strain (Koepp knew Michael Crichton and adapted some of his books for the screen). “Earth Abides,” he said, “focused on the aftermath of the civilization-ending plague and laid out a prophetic vision of what a post-civilized society might look like. … It is a wonderment of speculation.”

In the late 1950s, prolific movie producer Robert L. Lippert wanted to make a film version of Earth Abides, but after the box office failure of 1959’s The World, the Flesh and the Devil, his frequent collaborator, screenwriter Harry Spalding, convinced him that another last-man-on-earth film would be difficult to sell to America’s theatre-owners (Lippert himself owned a chain of 139 theatres). But just a few years later, Lippert decided to give the genre another try and bought the film rights to Matheson’s I Am Legend, which became The Last Man on Earth (Matheson didn’t like the film and took his screenwriting credit under the pseudonym Logan Swanson). As a fan of B-movies, I can’t help but wonder what a Robert L. Lippert-produced film version of Earth Abides might have looked like. It is one of the many great what-ifs of Hollywood cinema.

Fortunately, Hollywood has finally gotten around to embracing Stewart’s classic novel. Amazon Studios and the MGM+ streaming service have produced a six-episode limited series based on the novel and it is scheduled for release later this year, almost exactly 75 years after the book’s original publication date. When the project was completed, showrunner Todd Komarnicki told Deadline magazine, “It has been an unmitigated thrill to adapt such a seminal sci-fi work, and the themes illuminated by George Stewart 75 years ago could not be more meaningful and timelier for the world we are living in today.”

It will be interesting to see exactly how Komarnicki and company have adapted a novel so light on plot. Earth Abides is the story of Isherwood “Ish” Williams, a graduate student of ecology at UC Berkeley. When the novel opens, he is in a wilderness area of Calaveras County, California, conducting research for his thesis. On page one, he is bitten by a rattlesnake and retreats to a nearby cabin where he holes up for a day or two, feverish and delirious. He doesn’t know it yet, but while he has been alone in the wilderness, an “unknown disease of unparalleled rapidity of spread” has killed off nearly everyone on Earth. Stewart doesn’t spell it out, but the rattlesnake venom seems to have spared Ish’s life. Later, he will meet other survivors, at least one of whom was bitten by a rattlesnake at some point in her life. Of the disease, Stewart writes:

No one was sure in what part of the world it had originated; aided by airplane travel, it had sprung up almost simultaneously in every center of civilization, outrunning all attempts at quarantine. … It might have emerged from some animal reservoir of disease; it might be caused by some new micro-organism, most likely a virus, produced by mutation; it might be an escape, possibly even a vindictive release, from some laboratory of bacteriological warfare. The last was apparently the popular idea. The disease was assumed to be airborne, possibly upon particles of dust. A curious feature was that the isolation of the individual seemed to be of no avail.

With its many obvious parallels to recent events, it’s easy to see why the executives at MGM+ might have thought that the time was finally right for Hollywood to tackle Stewart’s novel. Although the recent pandemic killed “only” about 20 million people worldwide, Stewart’s novel allows us to see what might have become of the planet and its inhabitants had COVID-19 proved to be much more lethal. The most recent American edition of Earth Abides was published in the plague year of 2020 and includes a new introduction written by novelist Kim Stanley Robinson that April in which he explicitly makes the connection between Stewart’s fictional plague and our own real one. But he begins his introduction by noting that:

This novel, George Stewart’s masterpiece, is exceptionally ambitious, wide-ranging, graceful, and wise. It’s one of the greatest novels in the subgenre of science fiction now called post-apocalyptic (in Stewart’s time it might have been called an “after the fall” novel), and very worthy of the permanent place in science fiction and in American literature that it has achieved.

In the first fifty pages of Earth Abides, Ish returns to his family’s home on fictional San Lupo Drive in Berkeley (modelled on Stewart’s own home on San Luis Road) and wanders around the Bay Area looking for survivors. He finds a few but they are mostly castoffs and crazy people, driven mad by the Great Disaster, and Ish finds he has no desire to form a community with any of them. Just as the house on Cimarron Street serves as the focal point of I Am Legend, the house on San Lupo Drive will eventually become the focal point of Earth Abides. But first Ish takes off in his car for a trek across the United States. This opening section of the novel lasts about 45 pages and ends in New York City, where Ish and his dog Princess motor down a completely empty Broadway.

After that, he turns around and begins the long drive back to California. In many ways, this first section is the best part of the novel. It certainly appears to have been the part of the book that Stewart enjoyed writing most. It offered him a chance to muse upon just what might happen to the American landscape if humans largely disappeared from it. He describes house pets turning feral, adding:

As with the dogs and cats, so also with the grasses and flowers which man had long nourished. The clover and the bluegrass withered on the lawns, and the dandelions grew tall. In the flowerbed the water-loving asters wilted and drooped, and the weeds flourished. Deep within the camellias, the sap failed; they would bear no buds next spring. The leaves curled on the tips of the wisteria vines and the rose bushes, as they set themselves against the long draught.

Stewart had a gift for writing about nonhuman characters. My favourite character in Storm, other than Maria herself, is a wild boar he calls Blue Boy. In Earth Abides, Stewart writes movingly of the dairy cows who have starved to death in their milking barns, the thoroughbred horses who have died in their stalls, the house pets who can’t get out of their houses and die of malnourishment and thirst. He also reflects on what might become of the cattle now that the ranchers are all dead. With no men to kill them, wolves and coyotes are likely to proliferate again, and that will eventually keep the cattle population from overrunning the American West. He speculates about how the landscape will change as man’s dams and levies begin to fail.

This section of the book is so engrossing that it inspired journalist Alan Weisman’s 2007 nonfiction book The World Without Us, which explores how quickly planet earth might return to its natural state if mankind were to disappear. Dorian Lynskey remarks on this aspect of the novel, too:

What makes Earth Abides remarkable is Stewart’s serious engagement with the reality of an untenanted world. In most last-man stories, cities are largely intact, if sad and tatty, but Stewart, a prolific historian and toponymist, recognised that the world as we know it requires an enormous amount of maintenance. As Isherwood wanders equably around an unraveling America, Stewart keeps breaking off for lyrical disquisitions on what would happen if there were nobody to run the power stations, unblock the drains, fight the fires and do all those other jobs that we take for granted. How quickly it all falls apart.

All of this works very well in a novel, but it’s difficult to see how it can be made into riveting television. Fortunately for MGM+, Ish does eventually return to the house on San Lupo Drive, and he does begin to gather a community of survivors. He takes a (common law) wife, Emma, an African-American, and they have children together. Isherwood and Emma refer to each other as “Ish” and “Em,” which are ancient Hebrew words for “man” and “woman,” although Stewart doesn’t spell this out.

Many of the other survivors in Ish’s orbit also pair up and begin producing children. But as the last of the electric utilities finally dies out, Ish sees the younger generation of survivors begin to revert to a sort of pre-modern state of nature. Not all of this is entirely believable. Even in 1949, America was awash with handguns and rifles. But the younger generation of survivors tend to eschew these, preferring to use the bows and arrows they make themselves (they hammer coins, which are now useless, into arrowheads, Stewart’s clever way of symbolising capitalism’s demise).

At one point, some of the younger people decide to drive off to Los Angeles in order to see a bit more of the world before all the cars rust away and the roads are reclaimed by nature. When they return, they bring a menacing stranger named Charlie with them. For a while, it looks as though Charlie might become the great villain that this novel sorely lacks. But, although Charlie brings tragedy in his wake, he doesn’t become the story’s villain.

Ish sees post-apocalypse America as a dystopia, but it is not clear that Stewart did. And it is possible that Gen Z Americans who read Earth Abides today might even view it as a utopian novel. Strapped as they are with debt and dead-end jobs, many young adults in America today are struggling to pay rent, much less come up with the money to purchase a home. But in Earth Abides, money no longer matters and luxurious, untenanted houses are there for the taking. Elk and deer and other sources of meat roam freely through the streets, and growing your own food is fairly easy with so much open land available for cultivation.

Kim Stanley Robinson sings the praises of Stewart’s characters in his introduction:

The novel stays tightly focused on a single character, with a typical array of secondary characters. This is not to say that these characters are vague; they are quite distinct and well-drawn. Ish may be a kind of everyman, but his thinking and emotional life are clear and absorbing. He stands up well as a character even when compared to those in the mainstream novels of the 1940s that feature a hyperintense focus on a single consciousness. Ish’s interior life is lively, serious, intelligent, and believable. His angst over marrying a person of a color looks antiquated now, but was in keeping with the culture he was raised in, and a sign of how he has to change.

I agree with Robinson about Ish; he is a well-drawn and interesting character. But he is the only well-rounded character in the book.

As Wallace Stegner noted in his introduction to a 1983 edition of Storm, in Stewart’s novels “the characters seem to have interested him less for themselves than for their function as working parts of larger social entities—families, frontier communities, tribes, corporations, civilizations.” It will be interesting to see what Todd Komarnicki does with these mannequin-like secondary characters.

It will also be interesting to see what he comes up with for a plot. A group of Northern Californians undergoing a slow but largely undramatic return to the hunter-gatherer state of human civilisation doesn’t exactly scream “Must-see TV!” But whether or not MGM+ succeeds in making its version of Earth Abides engrossing, Stewart succeeded with his. Like most of his writings, it is a meditation on America—its landscapes, its animals, its people, its built environment, and its natural environment. Few authors have ever loved American geography more than Stewart, or written about it as well as he did. It’s a novel to savour rather than to race through.

V.

George R. Stewart was born in 1895 and died in 1980. During his creative life, he became part of a loose and unnamed school of writers that flourished in the mid-20th century. They were mostly highly educated males and often career academics who taught in west-coast universities and wrote knowledgeably about the American west.

Among the most prominent of these writers were Stegner (who won a Pulitzer Prize for Angle of Repose in 1972), A.B. Guthrie (who won a Pulitzer in 1950 for his novel The Way West, published two weeks before Earth Abides), Conrad Richter (who won a Pulitzer for The Town in 1951), Robert Lewis Taylor (who won a Pulitzer for The Travels of Jaimie McPheeters in 1959), H.L. Davis (born six months before Stewart and winner of a Pulitzer in 1936 for Honey in the Horn), Jack Schaefer (author of Shane, published a week before Earth Abides), Walter Van Tilburg Clark (author of the classic 1940 Western The Ox-Bow Incident), and George R. Stewart himself.

For most of the last 70 years, plenty of cultural critics familiar with these men and their works would have ranked Stewart among the least important figures in the group. Nowadays, that assessment appears to have been shortsighted. H.L. Davis is largely forgotten. Guthrie and Clark were both great writers, but they seem to be fading from cultural prominence. Ditto Schaeffer, Richter, and Lewis.

Hollywood seems to have no interest in these men, and they are exactly the kind of legacy authors who get dropped when school syllabuses are updated to make them more inclusive of women and minorities. Way back in 2009, Timothy Noah wrote an essay for the New York Times alleging that Wallace Stegner, a towering figure in the literature of the West, was already being forgotten. Even at Stanford University, where he ran the Creative Writing department for decades, his works are not widely known or read any longer.

But George R. Stewart, who was never that famous to begin with, seems to hang in there, year after year, decade after decade. Ordeal By Hunger, Storm, Fire, Pickett’s Charge, Names on the Land—every generation seems to rediscover these treasures and bring them out in new editions, with new introductions, and new interpretations of their place in the cultural landscape. Times change, literary fashions come and go, but Stewart abides.