Art and Culture

England’s Daydreaming

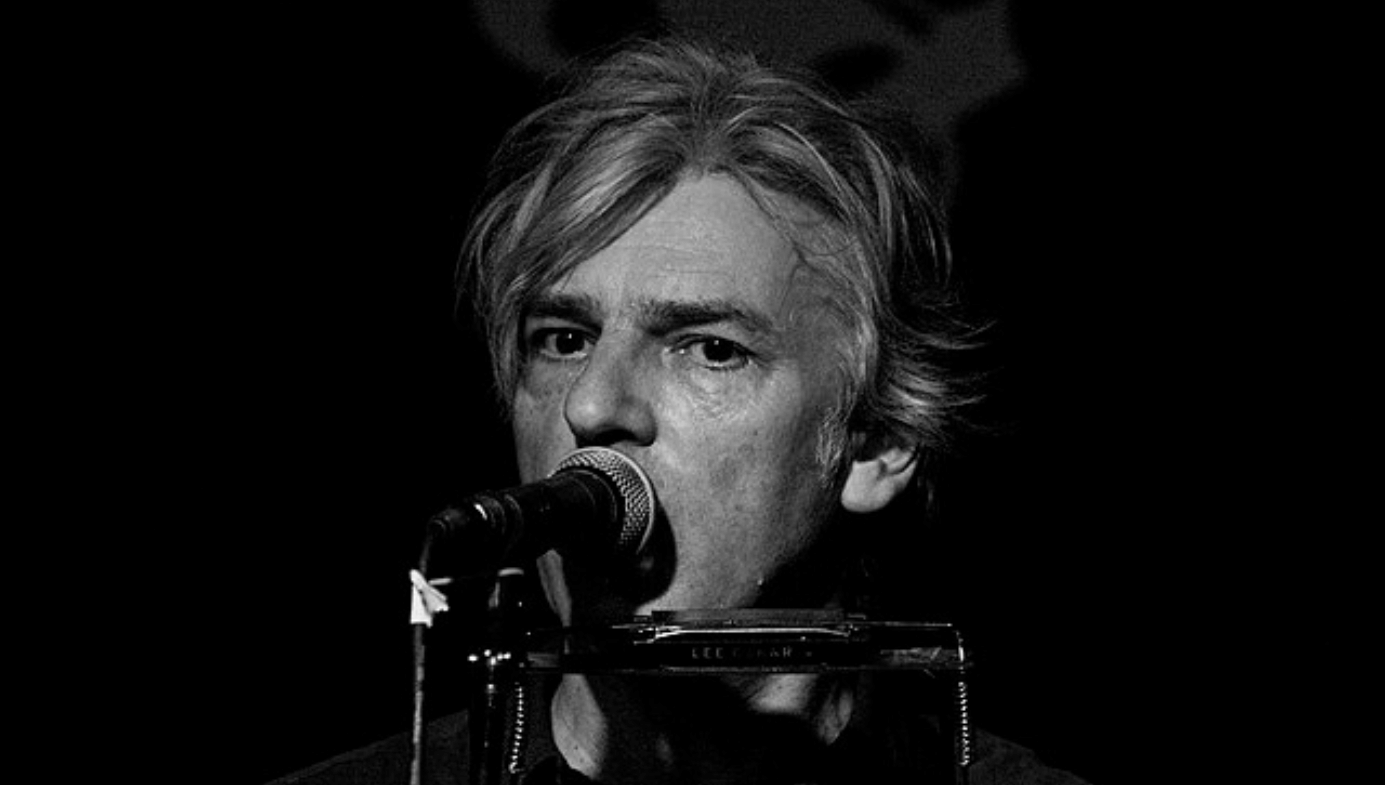

Robyn Hitchcock’s new memoir takes us back to 1967—a year the British singer-songwriter never outgrew.

A review of 1967: How I Got There and Why I Never Left by Robyn Hitchcock, 224 pages, Constable (June 2024)

He’s never had a major hit, he’s never been awarded a gold record, and he’ll probably never get into the Rock ’n’ Roll Hall of Fame. His best-known video never existed, and through the 1980s, he sold almost as many records in America, where they were never even released, as he did in his UK homeland. If there were any justice in this world (which of course there isn’t), he’d have been cast as Doctor Who the moment he outgrew his first pair of flares. That was, after all, his first ever ambition. “When I was young, I wanted to be Doctor Who. But then, when I was 13, I discovered Bob Dylan, and I wanted to be him instead.”

Robyn Hitchcock is perhaps the only living songwriter who can rhyme the word “love” with “periscope” and make it sound meaningful. His newly published memoir, 1967 How I Got There and Why I Never Left, effectively picks up at the moment he first heard “Like A Rolling Stone” and realised it was about him. Hence, the title of his book’s first prelude, “So Long Dalek Sponge.” “I should probably have been the Doctor after Peter Davidson,” Hitchcock told me in the mid-1990s. “It was all over after that.” Then he reconsidered. “But really, Doctor Who’s heyday was in black and white.” He laughed because so was Bob Dylan’s, after which, Dylan fell off his bike, retired to repair, and left the world an emptier place. The 13-year-old Hitchcock instinctively believed that he could fill that emptiness. He is now 71, and he still hasn’t come up with a “Like A Rolling Stone.” On the other hand, Dylan has yet to come up with a “Sometimes I Wish I Was A Pretty Girl,” so they’re just about even.

Hitchcock is not unaware of the dangers of retrospection. In that same 1995 interview, speaking of the songs he’d written over the previous decade, he explained, “I’ve constantly heard a few songs from my repertoire over the years, I sing a lot of them to this day, things like ‘Airscape’ and the ‘Dead Wife’ song [and] ‘Heaven.’ They’ve been around so long I can’t even imagine a time when I haven’t written them. And I’ve found that if you consistently remember one or two events in your life, that memory becomes its own reality. So when I listen to those songs on record, they don’t really sound like I think they do. They sound younger, the skin sounds fresher, the voice sounds squeakier, you can see my eyes poking just above my collar and my nose looks very small.”

His new memoir takes us back more than 20 years further, to when the collar was even higher, the nose was even smaller, and the voice was so squeaky that he still recoils from it today—“high-pitched and girlish, nowhere near breaking” is how he describes his tones in the book. He was living away from home for the first time, enrolled in the English public school system, sleeping in a dormitory with nine other boys, and trying desperately to navigate a course through this grave new world. Dylan, he writes, “seems to be addressing me personally, marooned in this nest of aliens. I miss my family, my world, my old school. At twelve years and ten months I’m already becoming nostalgic. But I can’t go back—time is a one way ticket.”

Hitchcock was born in 1953 in East Grinstead, a sleepy English town best known for the pioneering burns unit established at Queen Victoria Hospital during the Second World War, and for sitting smack on the Greenwich Meridian, the line that separates east from west. Neither of which impacted him. His earliest memories hail from his family’s “little white house on the cricket green” in Weybridge, and the “series of private nursery and preparatory schools” to which he and his younger sister were dispatched by their wealthy parents.

Clearly, Hitchcock flourished at Winchester, and his eye for minutia was already sharp enough that he could readily have devoted this memoir to the school itself—the arcane rituals and timeworn traditions a world away from the Swinging Sixties then underway; the rules (both official and cultural) by which the establishment conducted itself; the private Wykehamist language that he still remembers today; and the manner in which the school so firmly imprinted itself upon its charges. Because it did imprint itself upon Hitchcock, just as another of the great English public schools, Charterhouse, imprinted itself upon Genesis, the only band of note who (at least early on) shared Hitchcock’s lyrical gift for sounding as nonsensical as they were literate.

But Hitchcock’s memoir focuses instead on his second-most-profound influence, music. Music was not of any particular importance at this stage. He listened to the radio, he sang along with the hits, and he was overjoyed to discover that his school dormitory was equipped with a “home-customised record player … embedded in the wall by the fireplace.” The first time he became aware of it was as it spun the Beatles’ Rubber Soul LP. He was lucky that Winchester (unlike other schools of its ilk) seemed to have no strict prohibitions on the consumption of pop music. These little details are surprisingly significant, even if the recap of Hitchcock’s formative musical influences isn’t especially enlightening. Beyond Dylan’s unmistakable imprimatur, the dedicated fan will not need to be reminded of Hitchcock’s cultural debt to Sergeant Pepper, “See Emily Play,” and “A Whiter Shade of Pale.”

Thus, we are alongside him as he discovers a point of nomenclatural identification with Pink Floyd, whose frontman Syd Barrett spelled his first name with a Y rather than the more usual I, just as Hitchcock does. (Of such petty coincidences, we should recall, are teenaged tastes often shaped.) And we are with Hitchcock when, during the school holidays, he discovers David Bowie. “I’m wearing a purple nylon shirt with a big collar. A clever new song comes on the air: ‘Say you’ll be mine and I’ll love you till Tuesday.’ It feels like the singer is trying too hard, but it catches my attention.” That, too, for better or worse, is a condition that Hitchcock will carry with him into his own musical career—the ability, or perhaps the need, to over-egg his lyrical puddings with unexpected turns of phrase that are as self-consciously surreal as they are joyously daft.

Hitchcock employs that same trick in his writing. Of his first day at Winchester, where a spread had been laid out for parents depositing their offspring at its gates, he writes, “We’re ingesting tea and cake through the portals known as our mouths.” It’s a very Hitchcockian line, unnecessarily wordy but smirk-worthy just the same. In another world, it could have been a song lyric. A year into his career at Winchester, we witness his receipt of his first guitar, during a weekend at home at the end of February 1967. “My parents have acknowledged the change in me and from somewhere purchased a cheap but functional nylon-stringed guitar. A guitar! My own guitar! I pick it up in my fingers and turn it over. It’s a complete guitar. I’ve never handled one before.”

We share his joy when he takes possession of his own record player, a battery-operated machine loaned to him by a cousin. It is, he says, “life changing,” and he’s learning his first songs, Pink Floyd’s “Candy and the Currant Bun” among them. It goes, he reveals, “BOW—WUMP—BOWWW—WUMP—BOWWW—WUMP, DONG! BOW—WUMP—BOW—WUMP—BOWWW—WADDLER WADDLER, WADDLER WADDLER, WADDLER WADDLER, WADDLER WADDLER—SPAT!” And we are even there, a year later, when he buys the new Bob Dylan album, and discovers that even idols can have an off day. “John Wesley Harding was flat, beige, and not much fun to listen to. Nobody dared say they didn’t like it, but JWH didn’t spend half the time on the record player that Highway 61 or Blonde on Blonde did, and still do.”

By that time, of course, 1967 was over. “But it never ended,” he writes, not for him. Throughout the decade that followed, and those that picked up from there, “All along, I remained rooted in 1967: country rock, glam, funk, disco, reggae, and punk more or less passed me by.” He was happy when the UK music press, taking notice of him at the very tail end of the 1970s, described his band of the time, the Soft Boys, “as psychedelic revivalists.” But he knew “we weren’t really. … We were no more about ‘love & peace’ than the Sex Pistols were; we just used the old musical forms to encase my own take on human hell.” And, he acknowledges as the book concludes, “All the while, within me I’ve carried the soul of 1967 … a ‘stopped clock’ that ‘ticks on in me.’”

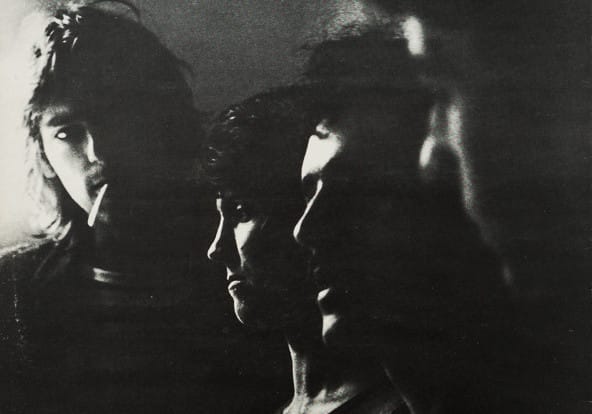

The first manifestations of this interest came courtesy of Maureen & the Meatpackers, the Worst Fears, and the Beetles, bands that Hitchcock formed in Cambridge, where he relocated when he left Winchester. “I don’t think the songs are particularly good,” he told me. “They were fun at the time, but they’re kind of hippy street theatre folk club songs for the mid-1970s. I think the first listenable stuff I did was with the Soft Boys.” Uncompromising, unrehearsed, and unrepentantly loud, the Soft Boys were still building a local reputation for themselves when the local Raw Records label added them to its own burgeoning catalogue of eastern England’s wilder talents. How they ever thought the Soft Boys would fit is a question few people would ever dare answer.

The Byrds—unmentioned in 1967, although their “Bells of Rhymney” would become a Hitchcock live staple—the Beatles, and Barrett were the Soft Boys’ most tangible influences: the former for the guitar sound, the latter for sheer inventiveness, and the Beatles because how could anybody have come of age in the 1960s without being touched by them? But Hitchcock was adamant when we spoke. While he insisted that “The first Soft Boys recordings were among the best things I’ve ever been involved in, I think,” he also conceded that “We were very loud on stage, and for whatever reason it didn’t really work in the studio. It was a very unstable outfit. I think we thrived off each others’ bad vibes. I’ve got a theory that the best music is made by people who can’t really talk to each other, and can only communicate through their instruments. So we co-existed by trying to drown each other out. Unfortunately, it just didn’t work on tape.”

Sales were poor, reviews were cautious. The band had to break up and Hitchcock had to launch a solo career before the Soft Boys catalogue could be reevaluated, not only as the source of some of his live show’s most popular songs, but also—again—as the blueprint for what, by 1982–83, was now a healthy psychedelic revival. Acts as disparate as the newly solo Julian Cope, the freshly painted Robert Smith, and the suddenly studio-bound XTC now joined Hitchcock in the stroboscopic bubble light. Still, Hitchcock stood apart from this crowd. His first solo album, 1981’s Black Snake Diamond Role, set the scene for much of what followed. The cracked vocals and crackerjack imagery could not have been further from contemporary expectations if he’d put on a baggy chequered suit and implored people not to call him Reg—which, of course, is what he did.

Overtly nodding to the general perception of psychedelia, Hitchcock recruited former Gong guitarist Steve Hillage to produce his next album, a smart move on paper but a disastrous one musically. Presented with the biggest budget he had ever seen (£112,000), a grand studio, and a host of name backing musicians, Hitchcock blamed himself for what happened next. “I wanted to do what other people were doing at the time, rather than doing what the Soft Boys had always been associated with, which was being retrodelic. I wanted ... to do something that sounded like it was of 1981. But it was done in the middle of the night when I was drunk, and I was recording it with a bunch of aliens, really. I’d stepped out from the usual circle of people, so I was a bit isolated.”

The upshot was “a complete abortion. I hated making it, I’ve never listened to it.” Three years after Groovy Decay’s release in 1982, Hitchcock issued his original demos as Groovy Decoy to exorcise the memory of its predecessor from the record racks. “Technology and I have never mixed successfully. Beefed up productions, high budgets, big promotional things, they’ve kind of presented their own versions of me, but it’s not me. Maybe you’ve got to be entranced by the technology, because I find that once music gets into technology, it goes into the hands of other people, and I have a lot of trouble communicating with them.” By the end of 1981, with technology practically taking over the music industry, Hitchcock had already lapsed into what amounted to fully-fledged retirement.

Resparking his 1967 self’s fascination with Bob Dylan, who also famously “disappeared” for 18 months, and reliving the dreams of Syd Barrett, who departed Pink Floyd in a tsunami of mythology, Hitchcock admitted, “All I really wanted was to sit there like a middle-aged dreamer, staring out over the bridge into the valley and blowing smoke out of my nostrils, reminiscing.” Surprised to discover how little the commercial failure of his two solo albums concerned him, “I thought ‘Why have a career? Why not just retire straight away?’” He had recently co-written a couple of songs for Captain Sensible’s hit Women and Captains First LP, “[and that] kept me going for quite a while. I did other odd bits and pieces as well, but nothing of note. I didn’t do any gigs, and I decided it was all over and I wasn’t going to perform anymore.”

His resolution lasted until spring 1983. Retirement itself was fine, he realised, but it was also very boring. Despite his best intentions, “I found myself stockpiling songs.” After a year spent recording demos, only a matter of days was required to record what became his third solo album, 1984’s I Often Dream of Trains. It was at this point that Hitchcock stepped into his own 1967—only instead of 12 months, it lasted for ten albums, a solid run that began here and would produce at least one album a year until 1993. Trains was followed by Fegmania (1984), the in-concert Gotta Let This Hen Out (1985), Element of Light and the out-takes collection Invisible Hitchcock (1986), Globe of Frogs (1988), Queen Elvis (1989), Eye (1990), Perspex Island (1991), and Respect (1993). Most of these were recorded with his new band the Egyptians, built around what he described as the first compatible musicians he could think of, Soft Boys Andy Metcalfe and Morris Windsor.

Largely recorded solo, I Often Dream Of Trains remains a startling breakthrough even today, and it is certainly the album most suited to playing while reading 1967. “Sounds Great When You’re Dead” and “Sometimes I Wish I Was a Pretty Girl,” in particular, capture Hitchcock’s love of Syd Barrett in both execution and delivery. Elsewhere, “Trams of Old London” and the title track both capture that sense of near-Edwardian whimsy that was common through the UK psych experience, sepia photographs of a world that is not so much gone, as never really there in the first place, but it ought to have been. That these blooms continued to flower throughout the years that followed is self-evident—they are still there in his music today. But the addition of a new band, The Egyptians, allowed his vision to expand even further. A 1985 issue of Melody Maker breathlessly pleaded, “As we near another oft-prophesied psychedelic summer, one can only hope it’ll be Hitchcock ... who spearheads the rebellion.”

That summer did not arrive in the end. Hitchcock, however, did not change course. With no hint of either derivation or retrospective longing, “Balloon Man” (1988) could effortlessly lie alongside the half-forgotten likes of Moonkyte, Boeing Duveen, and Frabjoy & The Runcible Spoon on any ’67-esque psychedelic compilation; “Oceanside” (1991) is one of the greatest songs the Beatles never wrote for Magical Mystery Tour. And so on. “Autumn Sea” (1989) is like a proggy ballad bisected by the Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band.

“My Wife and My Dead Wife” (1984) comes with its own mythology—the song itself is straightforward enough, but many people of a certain age also seem to recall an accompanying video that Hitchcock never made. The closest he came is the live performance included on 1985’s Gotta Let This Hen Out concert video, which is intercut with glimpses of a dead-looking wife, bedecked in lilies and full bridal drag, lying on an ironing board. But there was never was a video. Like the dead wife, it’s a phantom.

Hitchcock’s live shows were—and remain—equally resonant, peopled both by guest admirers (Peter Buck was an occasional stage invader during the mid-1980s) and the increasingly surreal stories with which Hitchcock would introduce songs (another trait Genesis indulged back in the days of Peter Gabriel). Never, however, was this devotion slavish, even when Hitchcock turned the spotlight directly onto his personal pantheon. When he covered the Beatles’ “A Day in the Life,” the protagonist “made the bus but I was dead”—not a line McCartney would ever have entertained. But when he devoted a full show to the 30th anniversary of Dylan’s 1966 Royal Albert performance, he brought this entire story full circle with an almost achingly earnest “Like A Rolling Stone.”

Today, of course, we are on the doorstep of that concert’s 30th anniversary, and Hitchcock remains active—as does Dylan. In fact, Hitchcock’s last vocal album, Shufflemania! (2022—its successor Life After Infinity is all instrumental) is his best in a long time. Yes, he’s slowed down. Yes, his flights of fancy are more firmly tethered to the ground than they once were. But “The Raging Muse”—Elastica’s “Connection” meets Tomorrow’s “My White Bicycle”—is as hard as you like, and “The Shuffle Man,” as Hitchcock puts it, is “the imp of change, the agent of fortune. He throws the cards up in the air and leaves you to deal with where they fall. He is the exhilaration of chaos—with fast hands and a stovepipe hat.” Exactly like 1967 (the year and, yes, the book) itself. The stopped clock ticks on.