Israel

Israel, Hamas, and Hezbollah

Updates on the military situation facing Israel, especially the possibility of all-out war with Hezbollah.

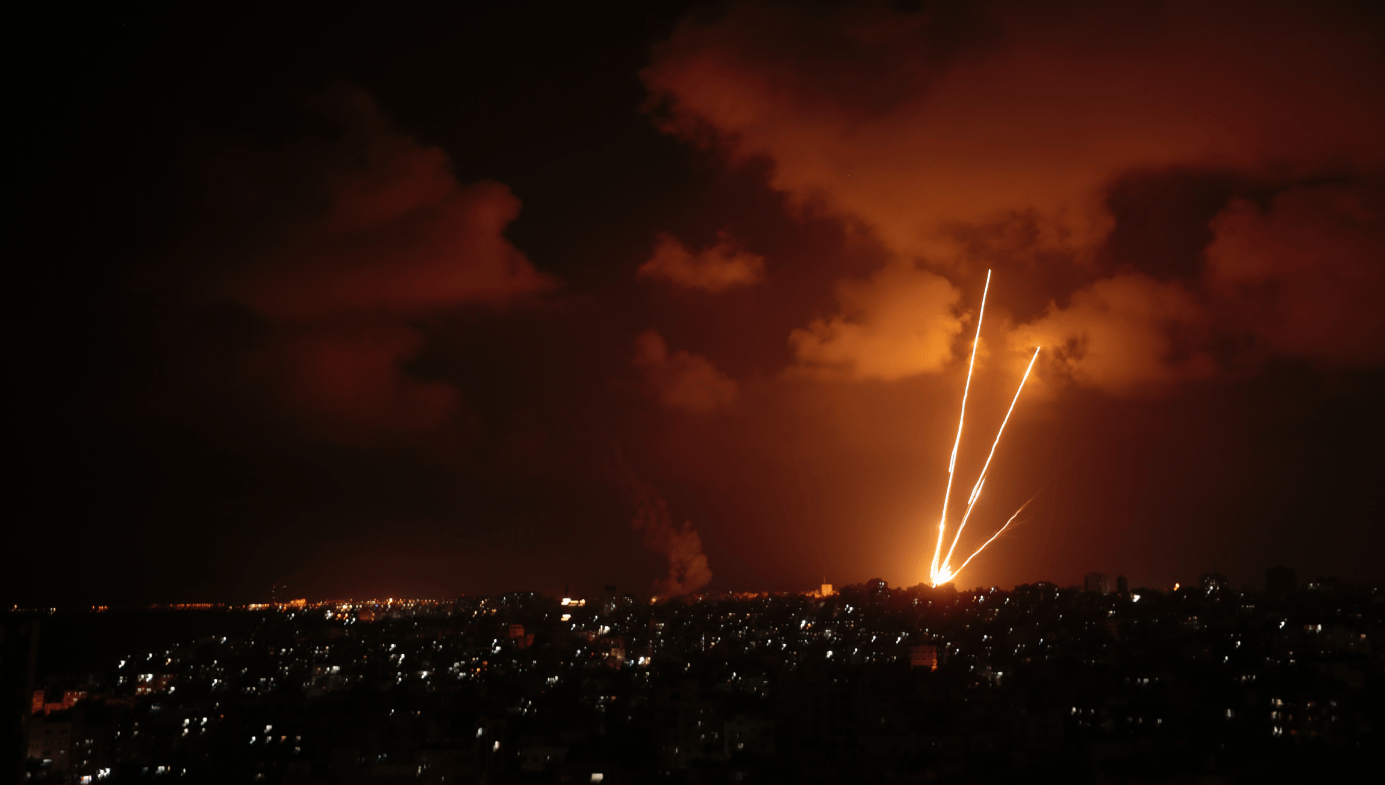

On 8 October 2023, the day after Hamas’s assault on southern Israel, Lebanon’s fundamentalist terrorist organization, Hezbollah, began raining down rockets on Israeli military positions and settlements along the Lebanese border strip. The Israeli government—foolishly, I believe—ordered the immediate evacuation of the strip’s civilian population southward and—more wisely—mobilised and deployed three IDF divisions along the border to deter a Hamas-like invasion by Hezbollah. Since then, for eight months now, the 70,000 civilians from the strip’s villages and the town of Kiryat Shmona have lived in cramped hotel rooms or with relatives in areas to the south, while Hezbollah daily fires daily rockets at the abandoned villages, which it rightly claims are now invested by IDF troops, and at IDF positions in the area. Altogether, Hezbollah has fired some 5,000 rockets and other missiles at Israel. The IDF has been retaliating against Hezbollah personnel, especially commanders, and targeting weapon stockpiles, safe houses, and bunkers in southern Lebanon, while making occasional strikes deeper into Lebanon, into the Beqaa Valley, a Hezbollah stronghold. Tens of thousands of Lebanese border villagers have evacuated northward, giving rise to an abandoned, free-fire zone on the Lebanese side of the frontier as well.

In this mini-war of attrition, both sides have tried to avoid directly harming civilians, mostly with success, although many houses have been destroyed and cultivated fields, crops, and forests have been devastated. So far, around 25 Israelis have died, most of them soldiers, and around 350 Lebanese, almost all of them Hezbollah fighters, including senior commanders. The highest-ranking Hezbollah casualty, Sami Abdullah (“Abu Taleb”), the commander of the Lebanese border area opposite Kiryat Shmona, died on 9 June 2024, along with three of his aides, when the IDF identified and targeted a safe house where they were meeting. Over the following two days, Hezbollah responded by showering northern Israel with some 300 rockets and missiles, targeting IDF bases as far south as the Sea of Galilee, more than thirty kilometres from the border, a first in this conflict.

This was a clear escalation of the eight-month-long duel. But, for the moment, neither side wants all-out war, which, if launched, would likely involve Hezbollah firing rockets at Haifa and Tel Aviv, Israeli air force bases, and civilian infrastructure, while the IDF would invade southern Lebanon and pound Beirut from the air, focusing on both Hezbollah’s main stronghold, the Dahieh neighbourhood, and on Lebanon’s vital infrastructure, thus crippling the country.

Hezbollah has been willing to play this high-stakes game in the knowledge that Israel is wary of starting a major war in the north while it is still battling Hamas in the south. Military analysts believe that Israel simply lacks the manpower and munitions to mount major offensives on both fronts simultaneously, especially given that Hezbollah is far more powerful than Hamas, with effective anti-armour capabilities. But neither the Shi’ite Hezbollah nor the official, multi-denominational Lebanese Army have either an air force or effective anti-aircraft systems—though over the past weeks Hezbollah has managed to down several large, high-flying Israeli drones.

Hezbollah has frequently declared that its long-term goal is the destruction of the Jewish state, in tandem with Hamas and with Iran, the patron of the two terrorist organisations. Hezbollah’s current harassment of the Galilee is geared towards weakening Israel, displaying solidarity with the embattled Hamas for the benefit of Palestinian, Arab, and Muslim eyes, and pinning down substantial IDF manpower and energies.

Hezbollah, which allegedly has an Iranian-supplied stockpile of 150–200,000 rockets and missiles, some of them able to reach Beersheba in southern Israel, and some 80,000 fighters, many of whom have combat experience from Syria’s civil war, where they helped prop up the murderous Assad regime, has shown resilience and innovativeness in battling the far larger and more sophisticated IDF, which has one of the world’s largest and most experienced air forces, a standing army of 160,000 conscripts, professional officers, and non-coms, and more than 400,000 reserve troops.

But given the demands of the war in Gaza and the mini-war in the north, with its potential to escalate into full-scale war, Israeli manpower is already stretched to its limits. In addition, the country is currently embroiled in a complicated internal struggle between the government and the opposition over the possible conscription of ultra-Orthodox (haredi) youth. The country’s two ultra-Orthodox political parties are a crucial component of Netanyahu’s coalition government and the ultra-Orthodox represent some 15 percent of the country’s Jewish population (and some 20 percent of the country’s conscription-age Jewish 18–21-year-olds). Since 1948, the haredi population, which has very high birth rates of 6–8 children per family, has successfully resisted service in the IDF. The embattled IDF General Staff is now pressing for their conscription.

It is possible that Iran and Hezbollah have deliberately inflated the number and quality of rockets and missiles in Hezbollah’s possession, in order to deter an Israeli assault against Iran’s nuclear plants—hoping to convince Israel that any such assault would be met by Hezbollah immediately firing rockets at Israel’s major population centres and industrial plants, including Dimona, the Jewish state’s main nuclear reactor where, according to foreign press reports, Israel produces its nuclear weaponry.

So far in the ongoing, eight-month-long mini-war of attrition, Hezbollah has restricted its rocket attacks to the Galilee. Its primitive, short-range, unguided Katyusha-style and Grad rockets have been mostly shot down by Israel’s Iron Dome anti-rocket missile system. But Hezbollah has also used Iranian-made suicide drones of the type Tehran has sold to Russia (and which Russia has used against Ukraine). The drones are slow, but they hug the ground and are therefore difficult to shoot down and they can be accurately directed to their targets by operators working out of well-camouflaged bunkers in southern Lebanon. These have wrought damage to a cluster of IDF bases. Another headache for Israel has been the use of Soviet-made Kornet anti-tank missiles, of which Hezbollah possesses large numbers. They have been used against IDF armour, abandoned civilian homes in the front-line villages, and the Israel Air Force (IAF)’s Northern Front Air Control Base on Mount Meron. These armour-piercing missiles are fast, flying directly to their targets in seconds, and cannot usually be interdicted. With the probable assistance of the Iranians, Hezbollah has upgraded the Kornets’ propulsion systems, doubling their original five-kilometre range. But so far, Hezbollah, which once announced that it would one day “conquer the Galilee,” has kept most of its crack Radwan formations, trained for cross-border raiding, out of the fight.

Washington fears that, amid the ongoing escalation, a miscalculation by either side or an incident involving many Israeli civilian deaths could trigger a full-scale Israel-Hezbollah war, possibly precipitating direct Iranian involvement. Washington has long feared being sucked into a new Middle Eastern war following its dismal decades’-long engagements in Afghanistan and Iraq. But some Israeli commentators would relish an expansion of the Israel-Hezbollah mini-war, which would give Israel—or Israel and the United States acting in concert—an opportunity to demolish Iran’s nuclear weapons project, which Israelis view as an existential threat, and which is clearly a long-term threat to America’s position in the Middle East.

However, Hamas and the Gaza Strip remain Israel’s primary objective. The IAF strikes since 8 October and the ground invasion that followed were Israel’s response to the massacre of 7 October, when Hamas and its junior partner, Islamic Jihad, invaded the Israeli settlements and IDF bases around the Gaza Strip, murdered 764 Israeli civilians and 373 security personnel, mostly soldiers, and took some 250 Israelis hostage, including women, babies, and geriatrics. Following a partial hostages-for-Hamas prisoner exchange in November and the rescue of a handful of hostages by Israeli commandos since then, Hamas retains around 120 hostages, only about half of whom are believed to be alive. The oldest Israeli hostage still in Hamas hands is Arye Zalmanovich, who is 86 years old and a survivor of the Muslim “Farhud” pogrom against Baghdad’s Jews in June 1941.

Hamas’s objective on 7 October was to kill and rape Israelis, sow terror, and subvert a possible normalisation of relations between Israel and the most important Sunni Arab state, Saudi Arabia, which would have cemented a Washington-orchestrated pact of “moderate” states to counter Iran’s terrorism and expansionist ambitions in the region. That pact is now on hold. The Israeli counter-offensive into the Strip had the aim of rescuing the hostages and destroying Hamas as a military and governmental organisation so that it can never again mount a 7 October-style attack.

At the start of the war, Hamas reportedly had some 30,000 fighters, organised in territorial brigades and battalions. The 7 October attack was spearheaded by its commando force, the Nuhba. Hamas apparently failed to coordinate its 7 October attack with Hezbollah or Tehran, but it clearly hoped that both these players, together with Iran’s other proxies and affiliates in the Middle East, including the Houthis in Yemen, militias in Iraq and Syria, and the Palestinian population in the semi-occupied West Bank—and perhaps Israel’s 2 million Arab citizens as well—would be sucked into the fight, thus presenting Israel with an unmanageable, extended, and perhaps unwinnable, multi-front war. But so far, while the West Bank population has been somewhat restive and the Houthis and the Iranian-orchestrated militias in Syria and Iraq have launched sporadic missiles and rockets at Israel and at international shipping in the Red Sea, Israel’s Arab citizens have remained strikingly quiescent. Indeed, a dozen or more of them were murdered by Hamas on 7 October and a number remain in Hamas captivity, while a handful of Galilee Arabs have died or been wounded by Hezbollah rocketry.

To be sure, the Hamas leaders, headed by Yahya Sinwar and Mohammed Deif, anticipated the massive Israeli counterassault on the Gaza Strip, calculating that thousands of civilians, among whom the Hamas and Islamic Jihad fighters were embedded, would be killed and maimed, creating chaos and a humanitarian crisis that would precipitate Western condemnations of Israel and perhaps even sanctions. In Hamas’s theology, Muslims sacrificed in a jihad against the infidel Jews are assured of martyr status and an enviable reception in heaven. The Hamas-directed Health Ministry in Gaza claims that 37,000 Gazans have been killed so far, more than half of them women and children. Israel says that the number is probably far smaller.

Be that as it may, the nightly images of Gaza’s dead and wounded civilians—but somehow never of Hamas fighters—on Western TV screens have substantially eaten away at support for Israel. This coverage comes on top of decades of media reports of Israel’s often brutal actions in the occupied West Bank, reportage that has groomed young people in the West into a gradually increasingly distaste for the Jewish state. By and large, these young Westerners know very little about the history of the conflict and still less about the savage ideology and praxis of Hamas: a murderous, misogynistic, homophobic, and anti-democratic organisation. And doubtless the dominance of Israel’s political landscape by Benjamin Netanyahu, a corrupt, immoral and manipulative man, has done nothing to endear Israelis to liberals in the West.

Hamas’s strategy going into the conflict was extremely successful. This strategy had four main pillars: (1) the element of surprise; (2) civilian human shields; (3) the tunnel network; and (4) hostage-taking.

(1) Hamas aimed to take Israel by surprise. The seventh of October was the Jewish holiday of Simchat Torah and many IDF soldiers were therefore home on leave. (The Egyptians and Syrians also successfully exploited a Jewish holiday, Yom Kippur, to launch a surprise attack on Israel’s denuded frontlines on 6 October 1973.) In addition, the Israeli forces based around the Gaza Strip had been depleted in the weeks preceding the attack, when the IDF transferred several battalions to the West Bank, where Israel feared an upsurge of terrorism. It is possible that many of the reports and rumours of impending terrorist attacks in the West Bank were engineered by Hamas. More significantly, Hamas relied on Israeli hubris (“we’re so powerful, they wouldn‘t dare”) and hoodwinked Netanyahu and Israel’s intelligence chiefs into believing that the organization was eager to accept cash and other financial inducements in exchange for tranquillity along the Israel-Gaza frontier. During the months before 7 October, Israel facilitated the arrival in Gaza of suitcases full of $100 bills sent by Qatar, Hamas’s main patron in the Arab world—the same country now posing as an honest broker and suitable intermediary in a possible hostage-prisoner exchange deal, which, given Hamas opposition, is unlikely to actually take place. During the weeks leading up to 7 October, Hamas, which had been firing rockets at southern Israel for years, stifled all anti-Israeli terrorism along the Gaza border.

(2) Hamas relied on the 2.3 million Gazan civilians—most of whom live in crowded urban neighbourhoods and so-called ‘refugee camps,’ which are actually suburban slums—to act as a human shield; training, bivouacking, and stockpiling their weapons behind, amid, and beneath their residences and educational, religious, and medical facilities. The Gazan population was—and remains, despite the blows it has received at Israeli hands since 8 October—overwhelmingly supportive of Hamas.

(3) Over the years, at the expense of billions of dollars, Hamas has built a vast tunnel network, reportedly comprising more than 700 kilometres of reinforced concrete passages 10, 20, and 50 metres underground, with electricity, water, and sewage systems and thousands of well-hidden or camouflaged entry/exit shafts leading down from residential buildings, hospitals, mosques, and schools. These tunnels, to which the civilian population has been forbidden entry, serve Hamas as command posts, air raid shelters, safe havens, assembly points, and bases from which to emerge and attack IDF invaders. Hamas has never built air raid shelters or bunkers for the Strip’s civilian population, so when the IDF counter-offensive began after 7 October, civilians had nowhere to shelter.

(4) Hamas’s battle plan for 7 October included taking many Israeli hostages. Dispersed in the tunnels, these hostages would serve as an additional human shield to inhibit IDF penetration into and destruction of the tunnel network and to protect the Hamas commanders ensconced within it.

To a large degree, Hamas’s strategy worked; the surprise succeeded beyond expectations; the tunnels afforded protection for thousands of fighters and their commanders; the presence of the Israeli hostages afforded Hamas fighters both above and below ground a large measure of protection; and the presence of the Gazan population restricted the IDF’s freedom of action when Israeli forces invaded the Strip.

In preparation for the IDF counterstroke, Hamas booby-trapped a huge number of residential buildings and institutions, as well as the tunnel network and the shafts leading into it, and fortified urban neighbourhoods. It heavily armed its fighters with rocket-propelled RPG-26 and RPG-29 grenade launchers, Kornet anti-tank missiles, improvised explosive devices (IEDs), and grenade-carrying drones. Hamas also deployed 81-, 82-, and 120-mm mortars.

After a fortnight of aerial bombardment of suspected Hamas positions and personnel, and repeated delays caused by Netanyahu’s hesitation, the IDF began its ground assault on 27–28 October, at the northern end of the Gaza Strip, attacking the main strongholds in and around Gaza City, Beit Hanun, and Beit Lahiya. Armoured columns, led by Merkava main battle tanks and armoured Caterpillar D-9 bulldozers cleared paths and toppled buildings and fortifications. They were met by thousands of RPGs and missiles, and the engineer (sapper) units sent into the shafts and tunnels encountered an endless series of booby traps. The extent of Hamas’s tunnel system surprised IDF planners.

The armoured columns, with air cover from fighter bombers and surveillance and armed drones, pushed forward slowly, as did the infantrymen, who, once dismounted, battled through the Strip’s urban neighbourhoods. The engineers and special forces units used mini-drones and dogs to scout out the tunnels and possibly booby-trapped buildings.

IDF casualties were relatively light. According to reports, the IDF had estimated that it would lose around 500 men in the invasion and conquest of the Strip. In fact, the IDF has so far suffered just over 300 dead and, at Rafah, is close to completion of the conquest phase. But some 4,000 IDF soldiers have been seriously injured and thousands more are suffering from post-traumatic stress and shell shock. A study published in March 2024, five months into the war, predicted that some 500,000 Israelis will ultimately suffer from PTSD, including 8 percent of all the soldiers involved in the fighting in the Strip.

The relatively low IDF death rate was largely due to the slow, careful pace of the IDF pushes; the IDF command, like that of most of the armies in the Western democracies, is wary of taking large casualties. Deaths were also minimised thanks to effective Israeli technology, such as the Trophy (“Windbreaker”) active protection system with which much of the IDF’s armour and D-9s are outfitted. The Trophy is a computer-operated system that consists of radar that spots incoming rounds and a “gun” that fires miniature projectiles to knock them down, all in a split second. Other contributing factors include Israel’s highly efficient military medical service; and its massive, pre-assault bombardment of suspected Hamas positions and Hamas-held buildings. The bombardments, of course, resulted in the mass devastation of buildings and infrastructure and many civilian deaths, leading to negative public opinion in the West and to some concrete sanctions, the most significant of which has been the American suspension of one shipment of aerial munitions to Israel.

Thousands of Hamas fighters died or were captured as the northern Gaza Strip towns fell, while the bulk of the civilian population, some 1.5 million people, fled or were pushed southwards toward Khan Yunis and Rafah, at the southern end of the Strip. But hundreds of Hamas fighters apparently remained underground, in the undetected or uncleared parts of the tunnel system.

In December, while leaving units along an east-west axis stretching from the Gaza-Israel border to the Mediterranean, many IDF units redeployed and attacked Khan Yunis, Yahya Sinwar’s birthplace and the Strip’s second largest city. Over the following weeks, much of the city was destroyed along with the local Hamas brigade, as well as part of its tunnel system.

Following the Khan Yunis campaign, in which the IDF failed, as it had apparently hoped to either kill Sinwar and Deif or free hostages—Hamas had probably moved the leaders and hostages to Rafah—the IDF released almost all the reservists called up at the start of the campaign.

It is unclear how badly Hamas has been hurt over the past eight months. Israel claims that 12–15,000 Hamas fighters have died, along with most of its brigade and battalion commanders, and that these military frameworks no longer exist. But the remaining fighters in the north and centre of the Strip are waging a low-level guerrilla struggle against the occupying IDF formations.

At the same time, Hamas has probably recruited thousands of new fighters to fill the gaps. The senior and middle-level commanders have been or are being replaced and some of the destroyed battalions are being reconstituted. Hamas still enjoys mass public support among Gaza’s civilians and continues to “govern” most of the Strip, meaning that it farms taxes, polices areas first conquered and then abandoned by the IDF, which lacks the manpower to blanket most of the Strip, and runs institutions like hospitals, while hijacking a large proportion of the incoming humanitarian aid and either storing it for its own uses or selling items like rice, flour, potable water, and even pineapples and bananas to merchants and shopkeepers to refurbish its finances. The current extent of Hamas’s munition stocks remains unclear, though they are probably running low. Over the past weeks, the IDF has taken control of the “Philadelphia” Axis, the strip of land running alongside the Gaza Strip-Egypt border, along with a large part of Rafah at the centre of the Axis, and has started destroying the tunnels—so far, the IDF claims to have uncovered 25 of them—through which Hamas was resupplied in the past with munitions smuggled in from the Sinai Peninsula.

To date, the IDF claims that it has captured 60–70 percent of Rafah, the last major Hamas-held bastion. The American administration and other Western players tried to prevent or at least greatly limit the Israeli assault on Rafah, but Netanyahu went ahead and launched the operation nonetheless, while offering the Americans assurances—which seem to have been upheld—that the IDF would try to keep civilian casualties to a minimum.

The conquest of Rafah will probably be completed over the coming fortnight, though many of the Rafah Brigade Hamas fighters have apparently slipped away to the north. This will bring Israel’s war against Hamas to a crucial T-junction. With most of the organisation’s main military units hors de combat, Israel will need to decide what to do, both in the south and in the Galilee. Neither the army nor the bulk of the Israeli public want a permanent military occupation of the Strip, which would entail caring for the civilian population’s needs while fighting a protracted guerrilla mini-war against the remaining Hamas fighters as they sporadically emerge from the tunnels. In this, the American administration, Europe, and the Arab world are at one with the Israeli public. But simply withdrawing the IDF from all or most of the Strip will result in Hamas’s re-emergence as the dominant, governing force in the territory and a reversion to the pre-7 October situation. A possible alternative course would be to introduce a third force into the territory to take control, say the Palestinian Authority, which controls parts of the West Bank and is led by Fatah, Hamas’s mortal enemies, or some coalition of the PA and moderate outside Arab actors, like the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia. But it is doubtful that the UAE, the Saudis, or any other outside Arab actor would be willing to enter the Gazan hornets’ nest or, if they did, to fight Hamas combatants, given that any Arab fighting Hamas would immediately be labelled an Israeli collaborator. In any case, Netanyahu does not believe that anyone other than the IDF can control the territory, suppress Hamas, and prevent it from regrouping.

But so long as Israel remains in the Strip and so long as the IDF, however reduced its presence, continues to fight the remnants of Hamas, Hezbollah has vowed to continue to harass northern Israel with rockets and missiles. To be sure, the end of major fighting in the south will free up IDF units to confront Hezbollah. But many Israelis, especially the military reservists, while they want the 70,000 displaced inhabitants of northern Galilee to safely return to their homes, are reluctant to embark on a new war, which most anticipate will be far more costly than the war now tapering off in the south. And while the IDF was able to more or less disempower Hamas, it is far from clear that this could be achieved vis-à-vis Hezbollah.

The Americans and French have been trying these past months to persuade Hezbollah to abandon its commitment to Hamas and agree to resolve its issues with Israel—which include some territorial adjustments it seeks along the Israel-Lebanon border, especially at the Shab’s Farms—through negotiation. But so far, Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah has not shown any hint of a willingness to compromise.

So, the mini-war of attrition along the northern border will continue and over the coming months, Israel will have to decide whether to embark on a full-scale war in the north, despite its depleted munitions stocks and a lack of enthusiasm among reservists who would be called upon to sacrifice more months of service and bloodshed. But without such an offensive, the population of the Galilee border area will continue to languish in hotel rooms as they watch their homes being trashed by Hezbollah rockets. For the Israeli government, this is a truly hellish dilemma.

But perhaps, with Iranian backing, Hezbollah will surprise everyone and itself initiate that full-scale war, calculating that an Israel weakened by eight months of combat and shorn of the world’s sympathy and support may prove a fragile target. Lastly, it is not unthinkable that Israel and Netanyahu, with their backs to the wall, may finally unleash the long-contemplated pre-emptive assault on Iran’s nuclear project, which by many accounts is fast-approaching weapons production. They may even use nuclear weapons if conventional means prove insufficient.