Art and Culture

Unbowed but Gravely Wounded

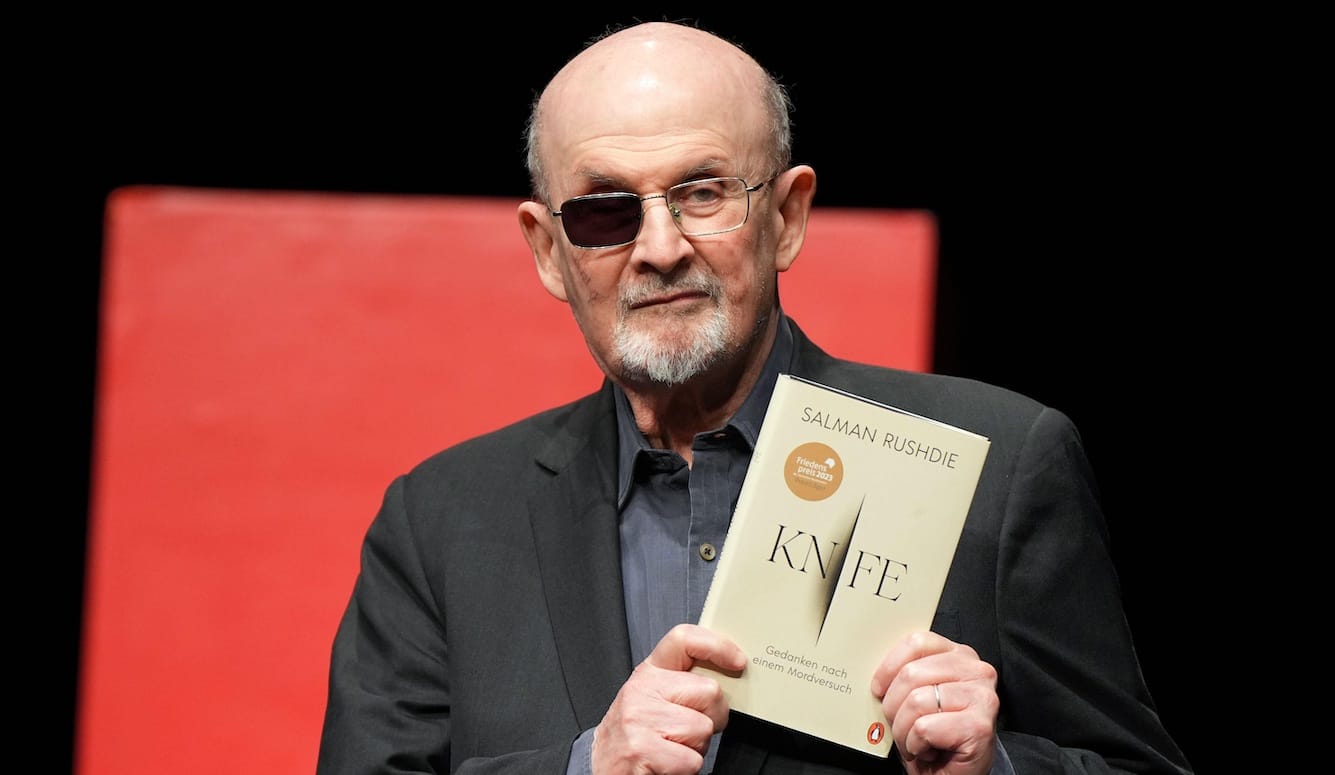

Salman Rushdie’s new memoir, ‘Knife,’ describes the assassination attempt its author survived and offers a moving contemplation of mortality.

A review of Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder by Salman Rushdie, 209 pages, New York: Random House (April 2024)

My copy of Salman Rushdie’s new book, Knife, arrived a few weeks ago, and before I had even opened the package, the news also arrived that Paul Auster had succumbed to cancer—and the confluence of Rushdie’s book and the information about Auster hit me harder than I would have predicted. Rushdie and Auster were friends. I knew this because in August 2022 there was a major assassination attempt on Rushdie—the assassination attempt is the topic of Knife—and a very few days later PEN America, the writers’ organisation, held a solidarity rally on the steps of the 42nd Street Library in New York. I attended, and I listened to Auster deliver a short speech. He celebrated Rushdie’s dedication to the storytelling imagination. He conjured the principle of freedom, and, in doing so, he expressed quietly an ardour of personal love, one friend for another in his moment of extreme trouble.

But it is Auster who has died, and the news has led me just now to reflect on the death, as well, of Rushdie’s close friend Martin Amis, who likewise succumbed to cancer, a year ago; and on the death thirteen years ago, again of cancer, of Amis’s best friend, Christopher Hitchens, the journalist, who was Rushdie’s friend as well. So I found myself gazing ruefully at the package with Rushdie’s book inside, and I was hit with the recognition that an entire chapter of Anglo-American letters appears to be nearly at an end—not entirely, of course, given that Rushdie does, in fact, have a new book. But his book is nothing if not a contemplation of mortality.

Perhaps it is less than appropriate to associate Auster with those other writers. Rushdie, Amis, and Hitchens took their first steps into the literary world under English skies, and they embraced a new existence in the far-away United States only later in life. Auster, by contrast, was a New Jersey boy whose own journey carried him across New York harbour to Columbia University and thence to Brooklyn, which was merely a commute. And his imagination always seemed to draw on the French, more than on the English.

Still, one of Auster’s books conjures, in a New Jersey and New York version, an atmosphere that shaped all of those people. This is his 900-page digitally titled novel 4 3 2 1, which recounts the progress of a New Jersey boy from high school to involvement in the 1968 student uprising at Columbia University. Nothing that happened among students in the United Kingdom in and around 1968 proved to be quite as riotous or imposing as the uprising at Columbia that year. And yet, the spirit of insurrection was more than American, and Rushdie, Amis, and Hitchens came of age breathing its vapours quite as much as did Auster in New York. And in one respect, all of those people responded in the same way, which was by cultivating a dandy exuberance in their prose, happy to attract attention to its own virtuosity.

This was the prose of writers for whom ebullience itself was a generational rebellion (as it was for a number of writers in France, as well). In Auster’s case, ebullience sometimes meant the construction of vast sentences, curling elegantly from one page to the next. And Rushdie, too, has made himself the master of the run-on and the strung-together, bubbling with delight at a colourful world and his ability to conjure it—not that Rushdie’s jolly and boisterous extravagances sound even remotely like Auster’s smooth complexities.

So three of that little group are gone, and the last man standing turns out to be Rushdie, which can only have left the god of actuarial probabilities, if such a deity exists, puzzled. Rushdie reflects on this in Knife: “There have been many times since the attack when I have thought that Death was hovering over the wrong people. Wasn’t I the one earmarked for collection by the Reaper, the one about whom everyone agreed that the odds were strongly against my surviving?” And yet Death was, in fact, hovering over Rushdie, too, even if, when it went in for the kill, some other fate or deity or happenstance chose to intervene.

The man who attacked Rushdie was—as he explains in Knife—a young person from a Lebanese Shiite background in New Jersey, who had visited the family home in Lebanon and returned to New Jersey in a tither of Islamist radicalisation. Rushdie was scheduled to speak at a legendary literary-and-ideas festival in the upstate New York town of Chautauqua. He took his place on the stage. And the young man from New Jersey, who knew barely anything about Rushdie, except that Ayatollah Khomeini had denounced him as an enemy of Islam worthy of death, raced down the amphitheatre aisle dressed in black, which is how one terrorist after another has outfitted himself on the occasion of a martyrdom operation.

In the introductory chapter of Knife, Rushdie offers a description of what happened next that he calls a collage, consisting of bits of his own memory, together with what other people have reported. The collage is shocking. I will quote it more than minimally because, very unfortunately, in order to understand Rushdie and what he has done in Knife and in other books as well, you have to register some small part of the shock yourself:

At first I thought I’d just been hit by someone who really packed a punch. (I learned later that he had been taking boxing lessons.) Now I know there was a knife in that fist. Blood began to pour out of my neck. I became aware, as I fell, of liquid splashing onto my shirt.

A number of things then happened very fast, And I can’t be certain of the sequence. There was the deep knife wound in my left hand, which severed all the tendons and most of the nerves. There were at least two more deep stab wounds in my neck—one slash right across it and more on the right side—and another farther up my face, also on the right. If I look at my chest now, I see a line of wounds down the center, two more slashes on the lower right side, and a cut on my upper right thigh. And there’s a wound on the left side of my mouth, and there was one along my hairline too.

And there was the knife in the eye. That was the cruelest blow, and it was a deep wound. The blade went in all the way to the optic nerve, which meant there would be no possibility of saving the vision. It was gone.

He was just stabbing wildly, stabbing and slashing, the knife flailing at me as if it had a life of its own, and I was falling backward....