Politics

Chaos at the End of History

Even in rights-based and law-bound democratic societies, people tend to find new things to struggle over.

I.

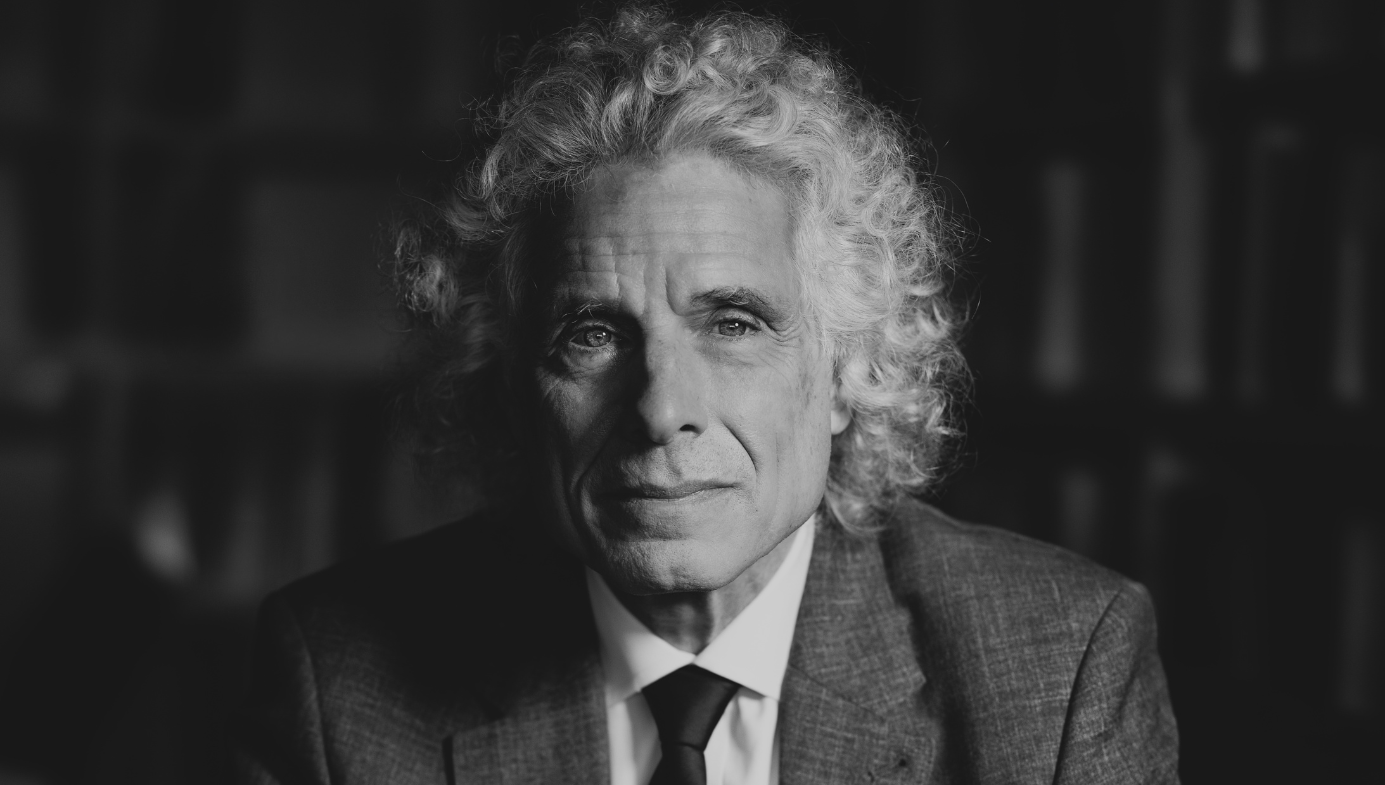

In a recent interview, I asked Steven Pinker what he thinks about Francis Fukuyama’s concept of The End of History. Pinker said he’s sympathetic to the idea that there’s “no longer any coherent alternative to liberal democracy as a defensible form of government,” and he observed that “there are many more democracies now than when Fukuyama published his essay in the summer of 1989, consistent with the direction of history he anticipated.” However, when I asked about Fukuyama’s concern that the prospect of “boredom at the end of history will serve to get history started once again”—an element of his argument that is often overlooked—Pinker said, “I don’t think the dystopia of ennui in a peaceful affluent liberal democracy … should be high on our list of problems. We should all have such ennui.”

Fukuyama’s The End of History and the Last Man is often regarded as the definitive example of post-Cold War hubris in the West. His critics argue that the book failed to anticipate a long list of ideological clashes and upheavals: September 11, populist authoritarianism in the US and Europe, the invasion of Ukraine, and the rise of aggressive Chinese nationalism. Many of these critics haven’t read the book or the essay that preceded it, or they would know that Fukuyama fully expected wars, demagogues, aggressive dictators, and political crises to continue filling the pages of the newspapers. His central argument was that capitalist liberal democracy has proven to be the most durable political and economic system—an argument that’s every bit as compelling today as it was 30 years ago.

The evidence for Fukuyama’s claim that the end of the Cold War brought the “unabashed victory of economic and political liberalism” is all around us. Western Europe has been at peace since World War II. The total number of democracies has surged. The liberal-democratic world is far more prosperous than any civilization in history—the United States’ annual GDP alone is nearly $28 trillion, while global GDP (adjusted for inflation) was around $23 trillion when “The End of History?” was originally published in 1989. Meanwhile, democracy’s authoritarian challengers are foundering. Russia’s pointless war against Ukraine has made the country a global pariah (Moscow’s best friends are now North Korea and Iran), tanked the value of the ruble, and put immense pressure on its already-meager petro-economy. China, meanwhile, faces a crippling demographic and economic crisis—Chinese stocks have contracted by almost $6 trillion in just three years as a massive real-estate bubble bursts and growth slows substantially.

Despite the remarkable success of liberal democracy, citizens are increasingly dissatisfied with it—particularly in the world’s most powerful democracy, the United States. An AP-NORC survey published last summer found that just one-in-ten American adults think their democracy is working well. Americans’ confidence in democratic institutions has plummeted—only eight percent say they trust Congress a “great deal” or “quite a lot,” while 26 percent say the same about the presidency. Even trust in the US Supreme Court, which has historically been higher than Congress or the executive branch, is near an all-time low: 26 percent. Surging political polarization has caused paralysis in Congress (threats to shut down the government and shatter the debt ceiling are now routine negotiating tactics) and led to deepening partisan acrimony throughout the country. Pew reports that Congressional Republicans and Democrats are further apart ideologically than at any point in half a century, while unfavorable views of both parties have increased more than fourfold over the past 30 years.

The expansion of democracy in recent decades has been historically unprecedented, but the civic decay in the United States is part of a larger move away from democracy around the globe. The world is less democratic today than it was at the beginning of the 21st century—from the spread of nationalist authoritarianism in the US, Europe, and India to the rise of belligerent Chinese totalitarianism (particularly after Xi Jinping’s elimination of term limits in 2018) and the revival of Russian imperialism. While the liberal-democratic world faces more dangerous external threats than at any point since the Cold War, the internal threats may be even more ominous. A decade ago, who could have imagined that an American president would attempt to steal an election? Or that he would then be rewarded with his party’s nomination and have a realistic shot at returning to the Oval Office?

In a 2020 lecture, Fukuyama reaffirmed his End of History thesis: “I have not heard anyone posit an alternative political-economic form other than liberal democracy tied to a market economy that I think will be a higher form of human civilization.” However, Fukuyama also acknowledged that the process of democratization has been more difficult than he anticipated. He considers his two-volume Origins series—The Origins of Political Order and Political Order and Political Decay—to be the sequel to The End of History and the Last Man, and the tone of those books is far from triumphalist. The Origins series covers many causes of political decay, such as institutional inertia, excessive constraints on decision-makers (which Fukuyama calls “vetocracy”), and “repatrimonialization” (which refers to small rent-seeking groups seizing control of public policy and resources). Fukuyama is also concerned about the rapid growth of identity politics, which urges people to focus on their membership in smaller and smaller identity-based tribes instead of their role as citizens in a large and pluralistic liberal society. He discusses this phenomenon in his 2018 book Identity: The Demand for Dignity and the Politics of Resentment.

But the source of political decay that may be most relevant to the democratic crises we face today is discussed at length in The End of History and the Last Man. In 2020, Fukuyama summarized the argument in just four words: “People want a struggle.” For many, peace and prosperity aren’t enough. The citizens of liberal democracies today are among the most fortunate human beings who have ever lived. Their societies are stable, rich, and free. They have access to technology and resources that would have been unimaginable just a few decades ago. While it’s true that inequality is rising, social spending as a share of GDP has increased dramatically since the 1960s. Life expectancy, GDP per capita, and leisure time have all risen, while pollution, warfare, and violent crime have fallen. Yet it’s difficult to remember a time—particularly in the United States—when politics was more deranged by tribal hatred, conspiracism, and cynicism.