America was founded in 1776 by men who believed that there were things worse than death—that principles enjoyed primacy over the sustenance of life for its own sake. They knew there was a good chance they would either die during their insurrection or be hanged later if they failed. Their letters and journals reveal that they worried about what punitive indignities the British might visit upon their families. But passivity was not an option. “We of this Generation,” wrote John Adams, “are destined to Act a painful and a dangerous Part, and We must make the best of our Lot.” Or consider this from John Jay: “The consciousness of having done our duty to our country and posterity, must recompense us for all the evils we experience in their cause.”

Around 6,800 Americans died on the battlefield during the War of Independence, while perhaps 20,000 more died of injuries and/or disease, many in British captivity. That estimated tally represented 0.8 percent of the total US population, which at the time stood at a mere 2.5 million. That is an astonishing number. An equivalent death toll in today’s America would be 2.7 million.

Some 186 years later, on June 6, 1944, the nuclear age was still a year away, but as they stormed Omaha Beach, the men of Operation Overlord knew that their chances of survival were slim. Certainly those in the second and third waves of the assault knew it. They saw the horror arrayed before them: detached limbs, disemboweled brothers-in-arms keening in agony as the sand around them turned red with their blood. But the Allied troops—nearly 160,000 of them—kept tumbling out of the amphibious crafts, despite the macabre display before them. The invasion of Normandy eventually claimed 29,000 American lives.

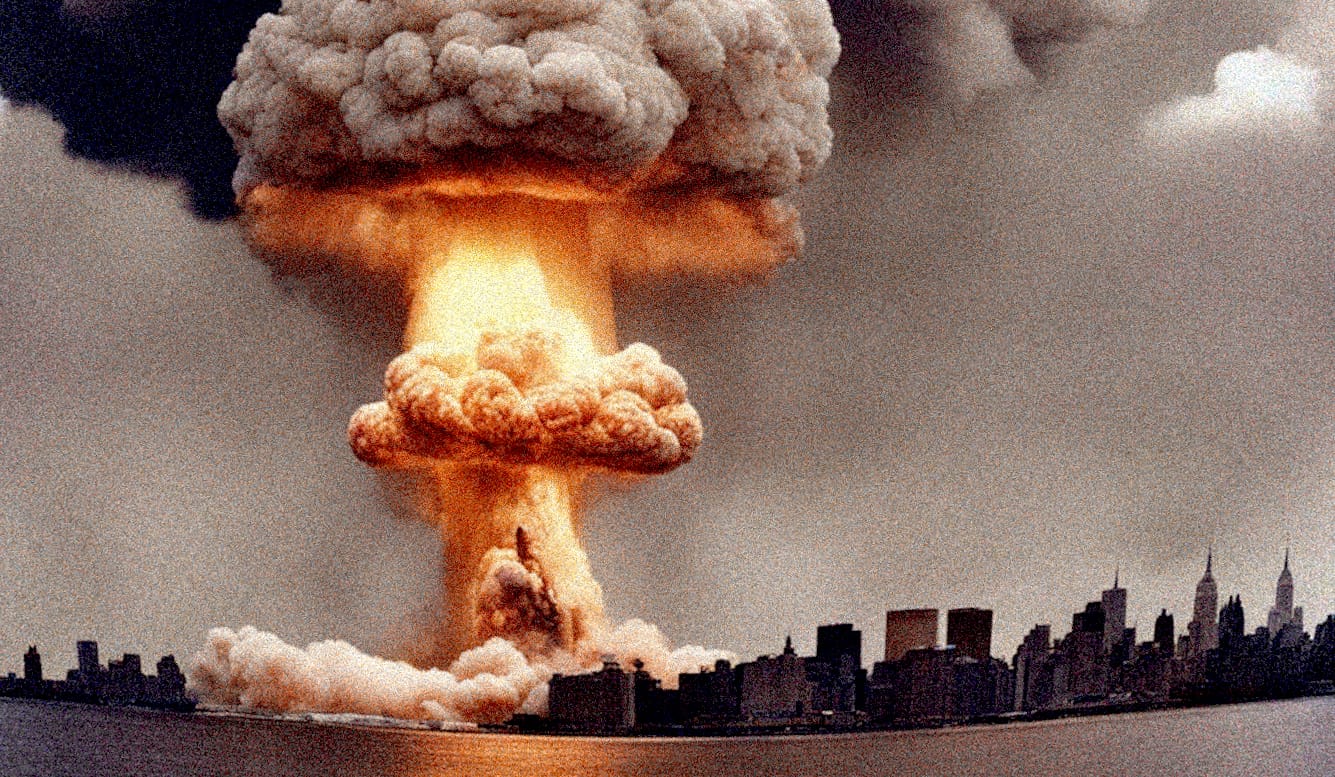

Eighteen years after D-Day, nuclear weapons were at the center of the Cuban Missile Crisis, when US president John F. Kennedy blockaded the island and presented Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev with an ultimatum. Kennedy had no way of knowing that Russia would back down. Ballistic-missile systems on both sides were in go-mode, and JFK would have (reluctantly) pushed the button. As he put it, “We will not prematurely or unnecessarily risk the costs of a worldwide nuclear war in which even the fruits of victory would be ashes in our mouth—but neither shall we shrink from that risk any time it must be faced.”

Following World War II, the disastrous consequences of appeasement were well understood, so preventing the Russians from installing ICBMs less than seven minutes’ flying time from the US mainland was thought to be worth the risk of confrontation. US leaders understood that a lack of will only emboldens aggressors and leads to further appeasement or surrender or a far bloodier fight later. Today, this is less well understood. From Main Street to Pennsylvania Avenue, we seem to have lost the will to fight, almost regardless of circumstances.

In November 2023, Gallup reported that 72 percent of Americans would not volunteer to defend the US in the event of a major conflict. In a contemporaneous Daily Mail poll, 30 percent of Americans aged 18–29 said they “would rather surrender than die fighting for the United States.” A third poll asked respondents if they would fight were the US to be invaded. Thirty-eight percent said they’d leave the country instead.

These findings are consistent with results I obtained a few semesters ago in a straw poll of my journalism students at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. I posed this choice: (a) go to war or (b) live under Chinese dominion. A majority said they’d learn Mandarin. “Are you aware of what life is like in China?” I asked. “Yes,” several replied, “it’s restrictive.” When I pressed them, asking if they’d be willing to entertain a forced conversion to Islam, a student admonished me, “Don’t be Islamophobic. It’s not our place to judge others’ customs.”