In 1941, at the height of World War II, troops stationed on Hoy in the remote Scottish Orkney Islands made a ghoulish discovery. Buried in peat on a lonely, windswept hill was the perfectly preserved body of a young woman, “her long dark hair curling about her shoulders.” Although the corpse was swiftly reburied, news of the macabre find inevitably spread. Soon, groups of young soldiers, eager for distraction from the boredom of a distant posting, began making “repeated excursions to the gravesite to exhume and view the remains” of the beautiful and mysterious “Lady of Hoy.” This morbid entertainment ended only when senior officers were told about the discovery and ordered the by-now decomposing body to be permanently interned under a concrete slab.

In life, the Lady of Hoy had been an 18th-century Orkney villager named Betty Corrigall, whose tragic story was sadly familiar. A brief romance with a visiting sailor ended in pregnancy and abandonment. Scorned by her deeply religious community, the distraught girl eventually hanged herself. Her body, that of a sinful suicide, was buried in unconsecrated ground, far from the scene of her shame, and forgotten. And so it remained for over a century and a half.

The story of Betty Corrigall helps to illuminate an ethical dilemma that has long dogged anthropology and archaeology: how are researchers to approach human remains and beliefs about the dead, particularly those from times and cultures very different from our own? This issue has become increasingly acute in the light of rapid advances in ancient DNA analysis. Those eager to embrace this emerging field argue that new technologies may yield greater insights into human prehistory and migration patterns as well as valuable knowledge of past human health and disease.

Others, mindful of the disrespect and desecration of indigenous burial sites in the past, contend that exploring the genetics of the dead is a “vampire science” that may result in “harmful social and political consequences.” These purported harms include undermining indigenous land claims, dismissing or disparaging traditional beliefs and oral histories, and potentially “reveal[ing] stigmatizing information like genetic susceptibility to disease.”

The Culture Wars Come for Archaeology and Anthropology

The spread of the culture wars into this debate is evident in a recent controversy over the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). Passed in 1990, NAGPRA sets out guidelines for the physical return of cultural items to Indian tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations. It also provides a process for the handling of new discoveries of Native American human remains and ancient sacred objects.

Some archaeologists, anthropologists, and think tanks have expressed concerns about “legislation creep,” and they worry that NAGPRA is being misread and inappropriately expanded. The original legislation, they argue, was not intended to restrict universities’ ability to study “culturally unidentifiable” human remains or artifacts that are not linked to a specific indigenous population. They say that such restrictions lie beyond the intended scope of NAGPRA and are dramatically limiting the ability of scientists to conduct important research.

In 2020, two prominent anthropologists found themselves in the crosshairs of this debate. Elizabeth Weiss and James Springer co-authored a book titled Repatriation and Erasing the Past, in which they objected to the alleged misapplication and overreach of NAGPRA. As a consequence, they were attacked as racist colonialists. Anthropologists and researchers from Australasia and North America said that the “violent language” of Weiss and Springer’s “colonial scholarship” revealed an “explicitly racist ideology” that is “deeply disrespectful to Indigenous people.”

Statements were published calling for the book to be retracted. A talk Weiss and Springer were scheduled to deliver at the 2021 Society for American Archaeology was summarily cancelled after colleagues accused the authors of being “anti-indigenous.” The SAA’s Queer Archaeology Interest Group (QAIG) claimed that Weiss and Springer were seeking to “foment tremendous anger and pain among SAA members,” and the Black Trowel Collective argued that the SAA’s decision to host the talk was “just one act in a long history, and ongoing present, of racist, misogynistic, and colonial discourse and action.”

We have released a statement of solidarity with our Indigenous colleagues that calls for archaeologists to participate in direct action to reshape the discipline.

— Black Trowel Collective (@BlackTrowel) April 19, 2021

The events at #SAA86thOnline are just the latest iteration of systemic problems within @SAAorg. pic.twitter.com/B5SJ6mHgqV

Weiss and Springer maintain that unless NAGPRA is returned to its original intent, archaeology will be guilty of “erasing the past” for ideological purposes, just as creationists distort the history of evolution. They contend that the “animistic creation myths” of indigenous peoples are being given priority over the “comparative, objective, and rigorous framework” of traditional anthropology. They’ve written academic and popular articles in response to what they and others see as bad science and overreach by those pursuing diversity, equity, and inclusion agendas for political purposes.

Evolutionary biologists Jerry Coyne and Luana Maroja agree, and believe that this anthropological brouhaha is an example of the “ideological subversion of biology.” In a recent article for Skeptical Inquirer, Coyne and Maroja analyze what they see as the increasing politicization of science, and the resultant “ideologically driven distortions of biology” to favor fashionable “progressive” causes. They point out that Weiss is a globally respected physical anthropologist at San Jose State University, where she studies 500–3,000 year old bones from California.

For simply studying those remains, Weiss was demoted by her university and banned from studying her department’s collection of bones. But it’s even worse: she’s not allowed to study X-rays of the remains or even show a photograph of the boxes in which they are kept. Many other universities, such as Berkeley, are also sending back or reburying artifacts and old bones. The result: valuable human history and anthropology remain off limits because remains and artifacts are considered sacred.

Coyne and Maroja argue that the progressive movement’s “desire to valorize oppressed groups” prioritizes religious feelings over empirical facts. And since “much indigenous knowledge … comes not from evidence but from authority or revelation,” this “simply prevents us from learning about our past.”

No anthropological endeavor is completely free from bias. Charles Darwin, for example, held and expressed views that are clearly racist, sexist, and classist by contemporary standards, and these attitudes influenced later social application of his ideas. On the 150th anniversary of Darwin’s Descent of Man in 2021, the prestigious journal Science published an opinion piece by Princeton University social anthropologist Agustín Fuentes that retroactively pilloried the book. Darwin’s views, Fuentes argued, “portrayed Indigenous peoples … as less than Europeans in capacity and behavior … offering justification of empire and colonialism, and genocide.” Employing hindsight a century-and-a-half after the fact, he further claimed that Darwin “validated” the views of modern “racists, sexists, and white supremacists.”

The outcry in Darwin’s defense was immediate and widespread, and Jerry Coyne was one of numerous prominent biologists who strongly condemned the Science article’s “distorting treatment” of Darwin’s “revolutionary” ideas. And so the merry-go-round of acrimonious criticism and counter-criticism continues.

Moral and Cultural Attitudes to the Dead

To move beyond the stifling polarization of identity-based disputes, we should seek common understanding by emphasizing that all human cultures possess unique traditions and customs related to death and dying. While the specifics may vary, underlying beliefs about death and death rituals represent human universals—inherent features of human psychology that exemplify the “psychic unity of humankind.”

Indeed, many cultural practices and beliefs are shaped by psychological tendencies that channel our thinking or behavior in broadly predictable ways. Consider “dualist thinking,” the belief that humans have a material body and an immaterial “soul” capable of persisting after bodily death. This innate “folk psychology of souls” helps to explain why concepts of spirits and ghosts are near-universal across cultures, and the ease with which children understand and accept these ideas. Human beings are predisposed to believe that something lingers after death, and even committed materialists usually feel that the mistreatment of human remains is somehow irreverent or sacrilegious. While dualist thinking is a psychological default that takes effort to overcome, the objectivity demanded by science does not come naturally to the evolved human mind.

How do these cultural quarrels play out in the case of Betty Corrigall’s interned remains? She was dead (yet preserved), which made her body culturally and psychologically taboo. That helps explain both the soldiers’ morbid fascination with her corpse and the officers’ disapproval of their behavior. But what was actually wrong with the soldiers digging it up? She was just lifeless matter, not so different from the once-flourishing plants that formed the peat that preserved her.

Although the soldiers’ voyeuristic curiosity caused no-one any harm, it nevertheless violated our common belief in the sacredness of death. Our evolved psychological tendencies bestow meaning on human remains. It may be a myth, especially to secular science, but it’s a dominant belief nonetheless, and its shadow floats over all graves, including those of indigenous peoples. It is therefore understandable that the odious history of grave-robbing in the name of science is deeply distressing to many, and not just a form of ideological faddism.

With that in mind, anthropologists and geneticists should be more sensitive to this shameful aspect of scientific history and to the psychological distress that disrespect for the dead may cause, even to people unrelated to the departed. Nevertheless, while evolved psychological predispositions may influence cultural beliefs and behaviors concerning the dead, customs and traditions are not necessarily fixed as a result. Those who purport to speak on behalf of these communities have a responsibility of their own to recognize that beliefs about the dead can also evolve over time, even within traditional cultures, and should always be balanced against other practices, including scientific endeavors that can benefit others.

Changing Times

From a modern liberal perspective, Betty Corrigall’s story draws attention to the cruelty of the social attitudes that led to her death. While it is possible that she accepted the community beliefs that led to her condemnation and subsequent suicide, such bigoted views are no longer acceptable in the liberal West. Moral attitudes have changed. The same is true of numerous other now-outdated historical customs and behaviors. In Betty Corrigall’s time, for example, the barbaric transatlantic slave trade was still in operation, as was the heinous practice of burning female (though not male) criminals at the stake. Yet no reasonable modern Westerner would call for these traditional practices to be reintroduced.

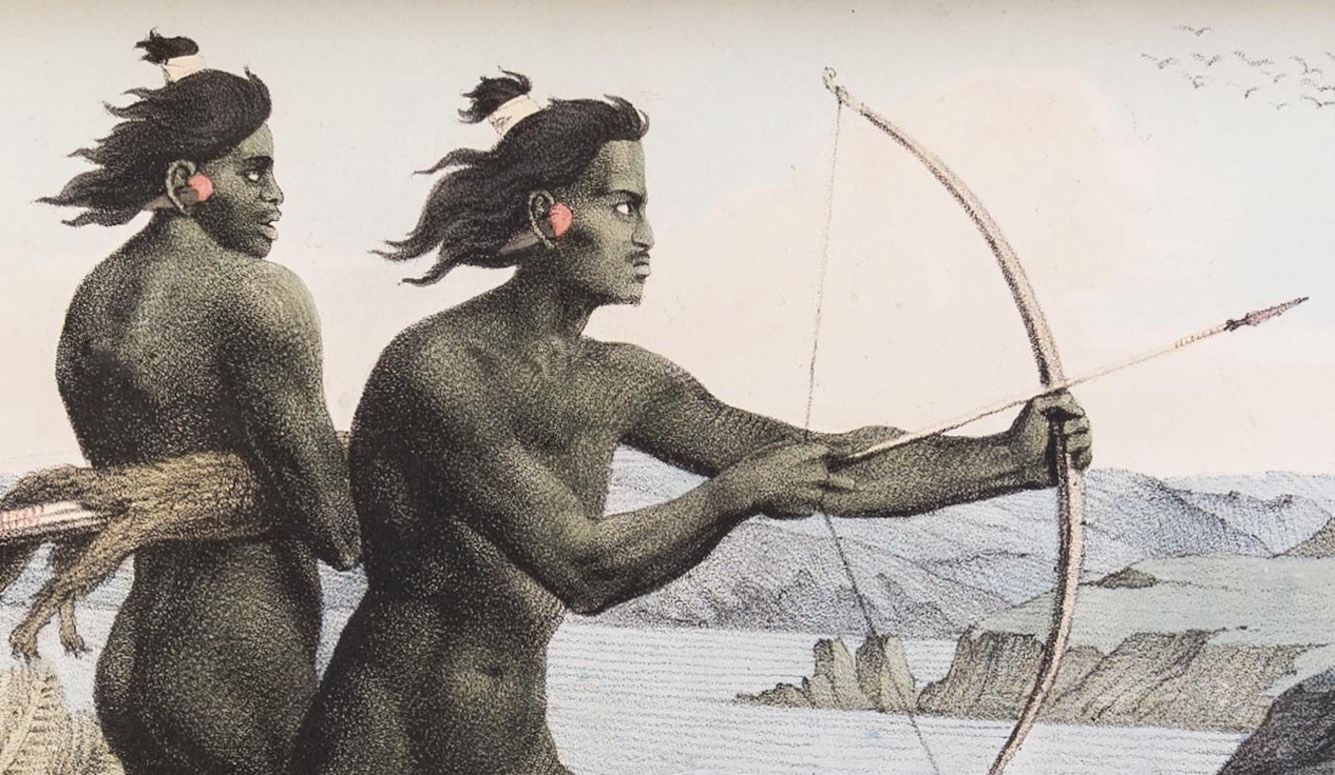

Just as Western societies have changed (rapidly and recently), so have indigenous cultures. Slavery and human sacrifice were once practiced in many historical indigenous cultures, and ritual cannibalism was practiced in others. Today, no indigenous person would defend those practices as appropriate to their modern lives. “Authentic” traditional culture, as postmodernists might agree, is an elusive concept. Modern indigenous peoples do not see the world through the eyes of their ancestors, just as modern Westerners no longer share the worldview of their forebears.

The irony is obvious: many self-appointed protectors of indigenous culture who rail against the “colonization” of a sacred past are themselves imposing idealized and condescending European notions of the “noble savage” on indigenous societies, protecting their remains with no exceptions. But does intent not matter? What if archaeological excavation offers scientific benefits that serve the greater good or a tribe’s yearning to better understand its own history? Should excavating DNA be treated the same as extracting skulls or other skeletal remains from burial sites?

Yes, many (but by no means all) indigenous cultures historically venerated their dead and gave obeisance to the spirits of the deceased. But how that was expressed, historically and today, varied dramatically from one culture to another. There is no universal view of how to handle ancient remains. There are no ethical qualms about digging up ancient hominin ancestors such as Neanderthals or excavating skeletons from the sunken Titanic.

Many archaeologists have consulted and collaborated with tribes, some of which have allowed the excavation of DNA from their forebears’ graves, as the Colville tribe did in the case of Kennewick Man. Some tribes are honored by knowing more about their ancestors. Formal or implied blanket prohibitions, enforced by the public shaming of scientists, not only impedes scientific inquiry, it also robs indigenous cultures, who have a right to negotiate their own practices, of their agency.

While past custom can be a guide, any particular response to questions of identity and human remains is only one of several possible modern interpretations of historical tradition. By their very nature, novel problems require novel solutions. An aversion to genetic research into ancient remains is therefore only one of several possible modern interpretations of how to protect traditional cultural customs and beliefs that emerged long before such technologies were even available.

It is patronizing to presume that all members of indigenous communities share uniform perspectives, or that belonging to a particular group implies unanimous opinions and attitudes. Modern identity activists often represent an academic or urban elite and their claim to speak for a particular community is dubious. They may articulate political opinions that do not necessarily mirror the broader range of views within that community. As is often the case, the most vocal voices, especially those willing to stifle opposing viewpoints, may drown out the potential diversity of beliefs within a community. In the case of the NAGPRA dispute, for example, the outspoken opinions of certain indigenous individuals may conceal others’ curiosity about what modern genetic science can reveal about their ancestral history.

A (Genetic) Window into the Past

Blocking DNA analysis of ancient remains in the name of protecting indigenous people may deny us valuable practical, intellectual, and cultural knowledge that can help all communities, including vulnerable indigenous ones. Greater understanding of health and disease is one of the most obvious practical benefits of inquiry into the genetic ancestry of different populations. In Europe, for example, the accumulation of genetic data has shed new light on the history, spread, and causes of diseases, providing important insights into susceptibility and immunity to ancient plagues, and even Neanderthal genetic links to the recent COVID-19 pandemic.

Human genetics research is already skewed towards people of European ancestry, and this imbalance will only worsen if access to the ancestral remains of indigenous peoples is denied. This is particularly true where susceptibilities to certain diseases exist due to the genetic isolation of ancestral populations (as is the case with European Jews, the Amish, Basque Spaniards, and numerous other groups isolated by geography or tradition).

Research has already identified numerous disorders found primarily in Native American populations. STAC3 disorder (formerly known as Native American myopathy) is a condition that weakens the muscles that the body uses for movement. Human HOXA1 syndromes are rare disorders with complex neurological and systemic symptoms. The disorder, found among a few American Indian tribes such as the Navajo and Apache, can result in deafness and heart malformations. Restricting access to indigenous genetic information could hinder our ability to address their unique health challenges effectively.

It is worth noting that some critics opposed to DNA extraction have raised concerns about potential revelations of “stigmatizing information” related to disease susceptibility if genetic analysis of ancestral remains is allowed. It is as if the risk of stigma is worse than the disease itself.

Reviewing the Indigenous Rights Conflict Through the Eyes of Orkney

What about the potential intellectual and cultural benefits of increased understanding of indigenous genetic ancestry? Here we can return to the windswept Orkney Islands. In a heather-covered valley, a few miles from Betty Corrigall's lonely grave, lies the Dwarfie Stane, an ancient rock-cut tomb steeped in local legends of trolls and giants. Archaeological evidence indicates that the burial chambers of this isolated monument were carved out approximately 5,000 years ago by people “using nothing but stone or antler tools, muscle power and patience.”

The archaeological record has shown that this was a period of great cultural change throughout Europe, including Orkney, as the Neolithic Stone Age gave way to the Bronze Age. But was this dramatic cultural shift (indicated by material remains such as changes in pottery style) driven by the diffusion of new technologies and ideas or by the influx of new people?

DNA research has resolved this “pots or people” debate in archaeology. We now know that the movement of people from the steppes north of the Black Sea reshaped cultural practices c. 3000 BCE and that these people—and the diseases they brought with them—supplanted the established communities of Neolithic farmers and hunter-gatherers. Recent genetic analysis of burial remains in Orkney paints the same picture: the islands “experienced a wave of immigrants during the Bronze Age so large that it replaced most of the local population.”

Nevertheless, Orkney stands apart. Unlike in much of western and central Europe, where mass population replacement was predominantly led by males, “the Bronze Age newcomers to the [Orkney] islands were mostly women.” Furthermore, in another unique finding not seen outside Orkney, the indigenous Neolithic male genetic lineage “persisted at least 1000 years into the Bronze Age, despite replacement of 95 per cent of the rest of the genome by immigrating women.” For reasons that are still unclear, however, traces of this lineage disappeared (as occurred much more abruptly elsewhere) and it is no longer found in the modern Orkney population.

Tales of the Past

There’s more to these “absolutely fascinating” discoveries (to quote one of the Orkney genetic researchers). Unrelated research by linguists and cultural anthropologists has traced traditional folktales deep into the prehistoric past, with some dating back to the Bronze Age. Using phylogenetic comparative methods borrowed from evolutionary biology to analyze stories common to different cultures and languages, researchers have reconstructed a tree of Indo-European languages that track the descent of shared fables across time.

According to the findings, the tale of Jack and the Beanstalk, for example, “was rooted in a group of stories classified as The Boy Who Stole Ogre's Treasure. These may be traced back to when Eastern and Western Indo-European languages split more than 5,000 years ago.” Beauty And The Beast and Rumpelstiltskin, meanwhile, date to 4,000 years ago while a story about a blacksmith selling his soul to the devil “was estimated to go back 6,000 years.”

How does this apply to early Bronze Age Orkney? The newly arrived settlers not only brought new tools and technologies; they likely also brought folktales that have survived until the present day. It doesn’t take much imagination to see Bronze Age storytellers employing the remarkable acoustics of the chambers of the prehistoric Dwarfie Stane to weave captivating stories of giants and trolls, and of the boy who steals their treasure. Betty Corrigall and her fellow villagers would also have known versions of these same stories, passed down through countless generations—local variants of the fables most famously collected by Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm only decades after Betty’s death. The adaptation and variation of such stories—and indeed languages—across time and place mirror the processes of Darwinian evolution, with these cultural “memes” serving as analogues to biological genes.

Resolving Claims over Human Remains

Compare the expanding understanding of Europe’s human history—from population dispersals to particular diseases, and from food to fairy tales—with the similar potential insights that will be lost if scientific inquiry into indigenous history is shut down. Then consider the alternative: pairing scientific consilience with indigenous “ways of knowing,” not as a replacement (as some fear) but as a complement, circumscribed by the input and cooperation of native cultures. Such an approach could establish connections to broader facets of ancestral culture, while uncovering unrecognized patterns in early indigenous settlement and population movements.

Restricting research into ancient history does a disservice to modern indigenous communities (as well as exacerbating existing inequalities in genetic research along perceived “racial” lines). This stance is both unfair and infantilizing, as indigenous people share the same curiosity about the past as any other community. Scientific knowledge doesn’t necessarily abrogate personal beliefs about ancestral history nor destroy our appreciation of folktales, legends, and deeply held ancestral religious beliefs. To the contrary—if executed cooperatively, it can offer an enriched understanding of indigenous ancestry.

Which brings us back to we began, with Betty Corrigall. Visiting her lonely gravesite is a moving experience. Even the setting is evocative, high above Scapa Flow, the natural harbour at the heart of the Orkney archipelago. Despite the distance of centuries, one can only empathize with the plight of a poor girl who was hounded and then abandoned. As a species-typical human trait, empathy comes naturally—as, too, do the moralistic judgements of Betty’s fellow villagers who drove her to suicide.

Science is critical to rising above inherent human frailties. Yes, biology must acknowledge its shameful history of prejudice and intolerance. But there must still be room for greater engagement and for mutually beneficial cooperation between scientists and indigenous people. Such cooperation could not only benefit native cultures but all of humanity.