Indigenous History

Joseph Boyden Isn’t Indigenous. But his Historical Fiction Is Still Worth Reading

The author’s widely celebrated 2013 novel, ‘The Orenda,’ helped educate Canadians about their country’s colonial roots. It shouldn’t be cast into literary oblivion just because Boyden misrepresented his ancestry.

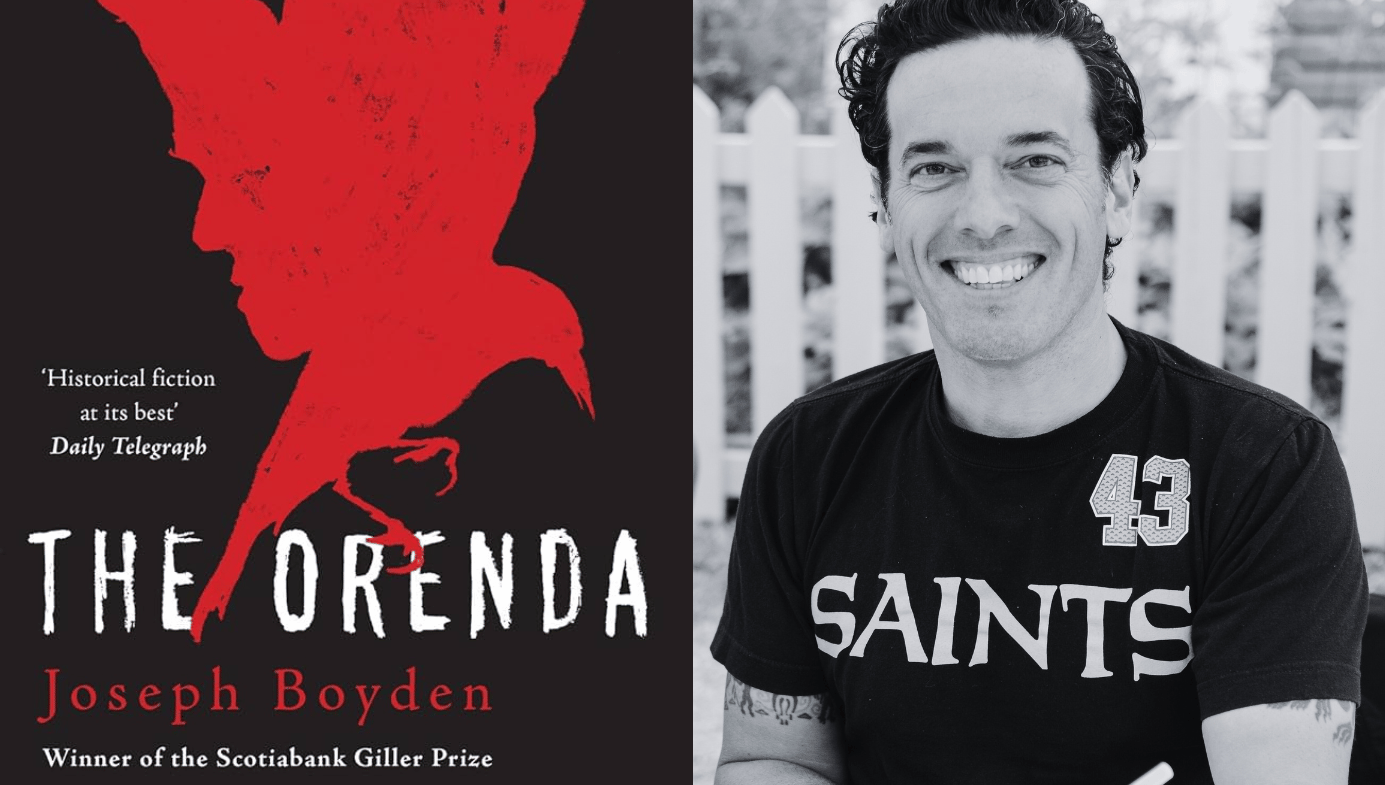

Canadian novelist Joseph Boyden isn’t Indigenous. The truth came out in 2016, a few days before Christmas, when writer Robert Jago asked, in a series of tweets, “Is Joseph Boyden actually native?”

Even as Jago was tweeting, the Aboriginal People’s Television Network (APTN) was working on a story about Boyden. It soon appeared under the headline “Author Joseph Boyden’s shape-shifting Indigenous identity.” Reporter Jorge Barrera wrote that Boyden had for years “variously claimed his family’s roots extended to the Métis, Mi’kmaq, Ojibway and Nipmuc peoples.” Barrera drew attention to Jago’s tweets and cited genealogical research showing that Boyden’s changing claims of Indigenous ancestry, in addition to being inconsistent, were all false. By January 2017, critics on Twitter were using the hashtag #CancelBoyden to call for Boyden’s speaking invitations and other professional opportunities to be withdrawn. Successfully, it would turn out.

Boyden’s change in fortune was stark. In 2016, he was the respected author of Three Day Road and other acclaimed novels on Indigenous themes—which had won the Giller Prize and other major literary awards, and had transformed Boyden into an enthusiastic spokesperson for Indigenous concerns.

By 2017, however, Boyden’s name had become, as a report in a Toronto-based newspaper, the Globe and Mail, put it, “a byword for ethnic fraud and cultural appropriation.” In 2017, Boyden gave a few interviews and wrote a magazine article in which he tried, without success, to defend himself from accusations of identity fraud. Since then, Boyden has been little heard from. As of this writing, no further books have appeared under his name.

Some observers have suggested that this is no great loss, as Boyden’s writing now has little worth. This view was expressed during a 2017 panel discussion at the University of Alberta. Janice Williamson, a professor of English and film studies, said, “I am not going to teach Joseph Boyden [as an Indigenous author]. He takes up the space of Indigenous writers.” Fellow panelist Norma Dunning, then a PhD student in education, went further: “If I were you, I wouldn’t teach Boyden. Period.” Since then, views similar to Dunning’s have regularly appeared on social media. As David Gaertner, a professor in the First Nations and Indigenous Studies Program at the University of British Columbia, tweeted in 2020, “Joseph Boyden should not be on your syllabus unless you are teaching a course on fraudulence.”

Williamson was making the fair point that in classes on Indigenous writers, Boyden’s work no longer has a place. But the thought that Boyden should no longer be taught, period, or only as an example of fraudulence, suggests that the revelation of Boyden’s identity snuffs out whatever value his fiction possessed. In this way, the backlash against Boyden has gone too far. If the case that Boyden misrepresented his identity is overwhelming, the case that we should no longer read his novels rests on a confused and complacent understanding of what it is for a writer to “appropriate” material from a culture not their own. Particularly in the age of Indigenous reconciliation, we should be reluctant to cast aside such richly imagined work as Boyden’s famous 2013 novel, The Orenda—which pulses with anti-colonial energy.

The case against reading Boyden hinges on accusations of cultural appropriation. Bu that term has become amorphous through its application to everything from outsiders writing songs about minority cultures to Indigenous land being seized at gunpoint. Should all of these activities be condemned in the same breath? Or could there be value in a non-native writer depicting native experiences, so long as it is done in a careful and informed way?

Thoughtful answers to these questions may be found in Cultural Appropriation and the Arts, a 2008 book by James Young, a philosopher at the University of Victoria. When cultural appropriation is wrong, Young suggests, it often involves the taking of artifacts or other tangible goods, such as land. Young points to events during the 1890s, when the Benin people of what is now Nigeria were fighting to maintain their independence after the arrival of British colonial expeditions. British soldiers plundered bronzes that had been made specifically for the Benin’s traditional leader, the Oba. These culturally significant artifacts ended up in the British Museum and other foreign institutions. By taking the bronzes without permission, Young writes, British soldiers engaged in wrongful object appropriation—a form of theft with added sting, given the cultural import of the items involved.

Young distinguishes object appropriation from the appropriation of artistic content that originated in a culture other than an artist’s own, such as a song, story, or motif. The Japanese director Akira Kurosawa engaged in this kind of appropriation when he used Shakespearean plots in his films.

A third category, subject appropriation, occurs when artists depict characters or institutions from another culture. Tony Hillerman, a mystery writer who wrote frequently about Navajo characters but was not Navajo himself, engaged in this kind of appropriation.

In Young’s framework, “appropriation” is not always a bad thing. Hillerman’s books, for example, for years were used in Navajo Nation schools. In 1987, the Navajo Tribal Council honored him with the Special Friend of the Dineh (Navajo) Award, which recognized him for “authentically portraying the strength and dignity of traditional Navajo culture.” Similarly, Kurosawa received critical praise for his creative use of Shakespearean plots.

Unlike the theft of objects, being artistically influenced by a different culture need not come at the expense of the autonomy of that culture’s members. They can continue to tell their own stories and describe their own experiences. As Young sums up his view, “cultural appropriation is often defensible on both aesthetic and moral grounds. In the context of the arts, at least, even appropriation from Indigenous cultures is often unobjectionable.” Young cites countless artists, from Picasso to jazz musician Herbie Hancock, whose borrowings from other cultures resulted in works that resonated with audiences of many different cultures.

Young’s book, with its careful distinctions between different forms of appropriation, as well as the overall view it expresses (one section is called “In praise of Cultural Appropriation”), offers a better approach than the one featured in heated literary debates over cultural appropriation. His account allows us to condemn the wrongful appropriation of objects and land, and a few stray cases of subject appropriation (such as that of the nineteenth-century missionary H. R. Voth, who violated the privacy rights of the Hopi people by taking pictures of sacred religious rituals). But when “cultural appropriation” is applied to literature, it is usually meant to condemn what Young terms “subject appropriation,” regardless of the details of the depiction. Young, by contrast, sees subject appropriation as not only permissible but a potentially positive aspect of an artwork as well.

Young is white. But prominent writers of diverse backgrounds share his view that a presumption against subject appropriation is a bad idea. Many years ago, I attended a reading by Tomson Highway, then and now one of Canada’s most prominent Indigenous writers. During the Q&A, I asked Highway what he thought of the idea that non-Indigenous writers should avoid writing about Indigenous people. His answer consisted of six words: “I don’t have time for it.”

The case for writing across cultural borders also was well-defended by the Palestinian literary critic Edward Said, whose work comprised a monument to anti-colonialism. He rejected the idea that “only women can understand feminine experience, only Jews can understand Jewish suffering, only formerly colonial subjects can understand colonial experience.” Said argued that such a view relied on a dubious cultural essentialism, as it failed to “acknowledge the massively knotted and complex histories of special but nevertheless overlapping and interconnected experiences—of women, of Westerners, of Blacks, of national states and cultures—there is no particular intellectual reason for granting each and all of them an ideal and essentially separate status.”

More recently, the notion that the meaning of a work of literature is fixed by the cultural origin of its creator has been satirized by Quebec writer Dany Laferrière, who is black. As he wrote in his novel, I am a Japanese Writer, “When I became a writer and people asked me, ‘Are you a Haitian writer, a Caribbean writer or a French-language writer?’ I answered without hesitation: I take on my reader’s nationality. Which means that when a Japanese person reads me, I immediately become a Japanese writer.”

Opposition to subject appropriation suggests a vision of the future in which Indigenous, black, or other minority stories can only be told when an Indigenous, black, or minority storyteller is available. It is hard not to see this resulting in a position of ongoing cultural privilege for narratives about Europeans and their descendants. Yes, we need more Indigenous, black, and other creators telling their stories. But we should hope to see Indigenous and other creators also become sources of inspiration in cultures beyond their own.

Many people other than Kurosawa have found Shakespeare to be a source of cross-cultural inspiration. Such borrowings are now the subject of an academic industry documenting Shakespeare’s influence in countries as diverse as Indonesia, Kenya, and China. Although his material is overwhelmingly European, his reach is universal. Like other great artists, Shakespeare travelled well thanks to colonialism, but he has also achieved his status in part because his content and subjects are thought to belong to everyone. Opposition to subject appropriation stands in the way of non-white artists achieving the same level of universal authority and acclaim that is bestowed on Shakespeare and other celebrated European creators.

The double standard that sometimes informs the reception of writers of colour has been pithily described by Indian novelist Amit Chaudhuri. “The important European novelist makes innovations in the form; the important Indian novelist writes about India.” As Chaudhuri elaborates, “this is a generalization, and not one that I believe. But it represents an unexpressed attitude that governs some of the ways we think of literature today…The American writer has succeeded the European writer. The rest of us write of where we come from.”

Chaudhuri refers to Indian writers. But what he says is true of how Indigenous ones are often thought about as well. Talk of “cultural appropriation” only reinforces the view Chaudhuri criticizes, which, despite its progressive veneer, subtly marginalizes the work of Indigenous, Indian, and other writers whose ancestry does not trace back to Europe.

Applied to Boyden, this suggests that we should distinguish the charge of identity appropriation from that of subject appropriation. The former is a wrong concerning how he represented himself. The latter is put forward as a wrong regarding his work that, upon examination, turns out to be dubious. There is nothing unethical in principle about a white author telling Indigenous stories or writing about Indigenous characters. No facts about an author, even an author guilty of something as serious as Indigenous identity fraud, are sufficient to determine the quality of the work they produce. The debate over subject appropriation endlessly directs our attention to authors, when we ultimately must return to the work itself.

The Orenda, published a decade ago, is set during the seventeenth century in what would later become northeastern Ontario. Among the Indigenous peoples who lived in this region, the Wendat, whose historic homeland lies between Georgian Bay and Lake Simcoe, were pre-eminent. They dominated regional trade to the point that other Indigenous peoples, from the Ottawa Valley in the east and perhaps as far away as modern Wisconsin in the west, had to learn their language as a condition of doing business. The historic rivals of the Wendat, the Haudenosaunee (who become known to the French as the Iroquois), lived south of Lake Ontario but hunted north of it. Their interactions with the Wendat took the form of ambushes and raids, to which the Wendat replied in kind, sustaining ongoing cycles of small-scale violence.

The Orenda opens with a Wendat headman and his warriors kidnapping a Haudenosaunee girl, a response to the murder of the headman’s family. On the same journey, the headman also captures a Jesuit who’d been sent from France’s new outpost at Quebec to convert the Wendat to Catholicism. The Jesuit, who takes turns with the Wendat elder and the Haudenosaunee child as narrator, refers to the Wendat and Haudenosaunee by their respective French names, Huron and Iroquois, one of many ways in which each narrator reflects their particular culture. Much of the drama of the story concerns the interactions between the Wendat and French, who insist that the Wendat tolerate a growing number of missionaries as a condition of being players in the fur trade; and between the Wendat and Haudenosaunee. Wendat expeditions to Quebec require travelling through Haudenosaunee territory, the dangers of which, high to begin with, were exacerbated by the kidnapping and the Haudenosaunee desire for revenge.

As political economist Harold Innis once put it, “the Indian and his culture were fundamental to the growth of Canadian institutions.” Without being didactic, The Orenda illustrated what Innis was getting at. The Wendat narrator observed Indigenous hunters coming from the north, “loaded with deer meat and pelts to trade for Wendat corn.” Long before the arrival of Europeans, the Wendat adoption of corn cultivation—a practice that is believed to have spread through Indigenous trade networks from ancient Mexico—had a positive effect on the Wendat diet, allowing the Wendat to settle in villages surrounded by palisades and cornfields.

It also gave them something of value to trade with neighbouring nations such as the Algonquin-speaking peoples to their north, who lacked arable land and were nomadic by necessity.

The fact that the Wendat were already experienced traders when Europeans arrived enabled them to assume a prominent role in the early fur trade. That they occupied settled villages also made them a convenient missionary target, further entwining their fate with that of the French colony at modern Quebec City, three-weeks away by canoe. The fact that Ontario and Quebec are part of the same country today originates, in part, with the trade and missionary arrangements made possible by the Wendat’s facility at agriculture. Likewise, the fact that Canada does not include upstate New York—despite it being much closer to Quebec City than Wendat territory—is in part because modern New York was largely controlled by the Haudenosaunee (who also mastered agriculture, occupied settled villages, and fought with the Wendat over hunting and fishing grounds).

Early in The Orenda, the Wendat headman takes a dislike to the Jesuit, whom he correctly recognizes as a threat to his way of life. When the headman finds the priest praying over the Haudenosaunee girl while she is asleep, he mistakenly assumes the Jesuit is about to sexually assault her, one of many episodes of cross-cultural misunderstanding. The Wendat narrator then has an opportunity to kill the priest, but the girl talks him out of it.

The headman later remarks that he should have killed the Frenchman when he had the chance, to which another character replies, “You know you can’t…the elders won’t condone it.” Which is to say that the Wendat leadership wouldn’t tolerate the open murder of the Jesuit because accepting his presence was a condition of trading with the French. The headman decides instead to take the Jesuit—derisively referred to as the “Crow” due to his long black robe—on a journey to Quebec in the hopes that he will die in a Haudenosaunee attack.

A long-standing European tradition of thought viewed the Indigenous peoples of the Americas as savages. A prominent representative of that tradition, the seventeenth-century philosopher Thomas Hobbes, sought to illustrate the proper function of government by imagining what it would be like to live in a state of nature. Hobbes had in mind not life out-of-doors, but life without the artifice of law or government, which regulate our interactions and checks our anti-social impulses, and which Hobbes considered a precondition of justice itself. Hobbes famously argued that such a state of existence would be so violent that people who lived in it would have “no knowledge of the face of the Earth; no account of time; no arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” Hobbes pointed to the “New World” as a place where people could be found living in such conditions. “For the savage people in many places of America, except the government of small Families, the concord whereof dependeth on natural lust, have no government at all, and live in this day in that brutish manner.”

In depicting Indigenous people as lacking culture and law, Hobbes was lending intellectual respectability to a prejudice already in circulation among European writers. This prejudice would serve to justify potlatch laws, which forbade the expression of Indigenous culture, and other instruments for the “improvement” of native peoples. The Orenda, by offering a historically accurate picture of Wendat life, shows how ill-informed Europeans such as Hobbes were in their understanding of Indigenous people.

One means by which the novel accomplishes this is through Boyden’s depiction of sex and family life. Early on, the Jesuit character decries local sexual mores as “shameless in their lack of modesty.” The Wendat did not require women to always cover their breasts, thought it was fine for both women and men to initiate sex, including outside of marriage, and did not consider monogamy especially important until after a couple had children. In these and other ways, their approach to relationships differed from (some would say improved on) that of their European counterparts.

One familiar attitude that Indigenous people held, however, was that they considered incest taboo. This meant that a person could form a family only by finding a partner who was not a relative. (In the Wendat case, this ruled out not only marriages between immediate relatives but also between cousins and other extended kin.) Contrary to Hobbes’s image of endless war between nuclear families, starting a family required cooperation with other family units, particularly those who would become one’s in-laws. The ties of extended kinship that resulted meant that it was possible to enforce cultural and moral norms, as Indigenous characters do throughout The Orenda, even in the absence of presidents and prime ministers.

And if the Wendat did not have Western political institutions, they still had governments of their own. Wendat society took the form of a confederacy. It was composed of at least four autonomous nations, whose names are sometimes translated as the people of the Bear, Rock, Cord, and Deer (and may have contained a fifth, the people of the Marsh). Each nation had its own governing council that would deliberate over trade, war, and other matters of national interest. Representatives of all the nations would come together at least once a year to address issues of concern to the confederacy as a whole.

A primary function of the confederate council was to suppress blood feuds and other violent disputes between members of different nations. The confederacy succeeded in doing this in part because different Wendat nations, estimated to have consisted of 30,000 people in total, at their height, shared a common language and culture.

The Orenda depicts meetings of the council of the people of the Bear, at which members gather around the fire and try to come to consensus, particularly in regard to interactions with the French and Haudenosaunee. It is because the council exists and wields political authority that the Wendat protagonist cannot simply murder the Jesuit. Although the inner workings of Wendat government are not a major focus of the novel, the novel still illustrates the core falsehood in the myth of Indigenous people living in a violent and anarchic state of nature.

After the Haudenosaunee girl is captured, she accompanies the Wendat leader and his men to Quebec (a detail that may strain plausibility, given how rare it was for women to go on such journeys). While at Quebec, a French fur trader attempts to rape her, only for the Jesuit to intervene. The girl’s assailant is then strapped to a stockade and publicly flogged with a cat-o’-nine-tails until he falls unconscious, after which the Jesuit again steps in to stop the violence. Although the Wendat who are at Quebec want the trader punished, they disapprove of the French authorities’ brutal methods. “What is the point of this torture,” one of them asks, “if he isn’t [mentally] present to understand its point?”

The frank depiction of a Haudenosaunee girl being assaulted by a French character is a break from previous narratives of early Canadian life, which were known to romanticize sex between European men and Indigenous women. Consider Company of Adventurers, Peter C. Newman’s acclaimed history of the Hudson’s Bay Company, published in three volumes beginning in 1985. The first sentence of Chapter One, The Bay Men, states: “For a time, they were trustees of the largest sweep of pale red on Mercator’s map, lording it over a new subcontinent, building their toy forts and seducing the Indian maidens they playfully called their ‘bits of brown.’”

Newman told history from the fur traders’ point of view, taking at face value their accounts of sex with native women as playful and fun, all part of the big adventure. Boyden’s narrative, perhaps because it is told mostly from Indigenous perspectives, is far less romantic, foreshadowing as it does the sexual abuse of native children that would be institutionalized in Residential Schools and other organs of colonialism.

One way a modern author might react to colonial narratives would be to reverse them: Morally exquisite Indigenous heroes triumph over depraved European villains. The Orenda rejects this strategy, which replaces one stereotype with another, in favor of a more complex approach. When the Wendat express bafflement at the cruelty that the French inflict in the name of justice, it is one of many instances in which Europeans are found wanting by Indigenous moral standards. (A similar moment occurs when some Jesuits are shocked to discover that the Wendat, unlike Europeans, never inflict corporeal punishment on children.) It is a testament to Boyden’s skill as a writer that these moments are always believable. The Indigenous characters have morally nuanced inner lives, with resignation to practices such as kidnapping coexisting alongside gentle parenting and other habits of mind that reflect a well-honed moral sense.

Although the Jesuit character is less sympathetic, moral complexity also informs his make-up. His interventions to stop torture and rape draw on recognizably ethical impulses. Yet at the same time, his presence ultimately is a disaster for the Wendat. Both aspects come together in his religious fanaticism, which motivates him to commit acts of bravery and mercy even as he seeks the destruction of Wendat culture.

As a Catholic, he would never agree with Hobbes that morality is a product of human artifice rather than God’s natural creation. Yet he shares the view that Indigenous people are savages and so in urgent need of his improvement. What he stands for is ultimately on display in a scene in which he uses his developing Indigenous language skills to proselytize at a Wendat village. “Great voice, he loves you. Great voice is son child deer Christ. Christ kill for you to become him. Christ kill me. Die. Death for you. Christ.”

The Orenda makes vivid many injustices to First Nations that were a deliberate part of the founding of Canada. For readers aware of subsequent Canadian history and the unfinished project of achieving a just relationship with Indigenous peoples, the effect of the book is to raise an old question with new force. That question was posed by anthropologist Michael Asch in On Being Here to Stay (2014), which takes its title from a famous passage, written by Chief Justice Antonio Lamar, in the Canadian Supreme Court’s 1997 Delgamuukw decision: “Let us face it, we are all here to stay.” Asch asks of people whose presence in Canada is a result of European settlement, “What, beyond the fact that we have the numbers and the power to insist on it, authorizes our being here to stay?” As befits a work of fiction, The Orenda allows the reader to imaginatively experience the history that gives this question force. As is also fitting, the novel calls this question to mind without answering it.

And yet even someone who accepts the idea that The Orenda is a respectable work of historical fiction, one that manages to inflame the reader’s sympathies without being programmatic, might still find fault with the fact that Joseph Boyden is its author. This view, or something like it, was suggested by the above-mentioned criticism that Boyden should not merely be removed from the reading lists of classes on Indigenous authors, but no longer taught at all.

This criticism is often expressed in a manner that assumes that Boyden “takes up the space” of Indigenous authors, not only in classes on Indigenous writing, but everywhere. Because it concerns the relationship of authors to other authors, rather than to texts, this objection is not rebutted by a defense of subject appropriation. But is this zero-sum view of reading really true?

Consider the history of Western films. When would have been the best decade to release one? Was it in the 1950s or 1960s, when the genre was at its height and Westerns were showing in every movie theater? Or was it after 1970, when the genre went into a long decline? If engaging the work of one creator inevitably comes at the expense of engaging similar work by others, then it stands to reason that the best time to release a Western would have been after the genre became less popular, as there would have been fewer Westerns competing for viewers.

But of course, it was during the period when the genre was popular that Westerns were most likely to find a wide audience. Rather than steal viewers from other Westerns, audiences who saw The Searchers (1956) were primed to also go and see The Magnificent Seven (1960). Of course, in the case of the Western, it is hard not to feel a sense of relief at the genre’s decline, due to its perpetuation of the myth of the open frontier and other anti-Indigenous tropes. But the same pattern holds true for opera, jazz, and other genres whose popularity has waned. The best time to produce them was typically when more similar works, not fewer, were widely available. Rather than ask which other works The Orenda has stolen attention away from, we might ask which other works gained larger audiences.

Historian Kathryn Magee Labelle, who specializes in Wendat history, has described the positive effect The Orenda had on interest in her area. “It is fair to say that Boyden’s book has brought the people and events of Wendake ehen (old Wendat country) back to the centre stage of popular culture,” she wrote in 2015. “Indeed, in my conversations at history conferences, workshops, and book launches, The Orenda is ever present, and the question is often asked: ‘As a Wendat historian, what do you think about the book?’’’ By way of answer, Labelle praises the novel as “a fair representation of the history that inspired it.” In addition, she credits the novel with inspiring readers she has met “to research further and find out the details behind the characters and events.”

Boyden may have made things easy for such readers by listing in his acknowledgements the works of nonfiction that inspired him. They include The Children of Aataentsic: A History of the Huron People to 1660 (1976), by Bruce Trigger, and Huron Wendat: The Heritage of the Circle (1999), by Georges Sioui. These and other works that informed Boyden’s research share a sensibility, one that is summed up in the subtitle of another book by Trigger (not cited by Boyden): Natives and Newcomers: Canada’s “Heroic Age” Reconsidered (1985). Trigger and Sioui belong to a generation of historians who did much to overturn the longstanding view that the early contact period was a time when jaunty European explorers encountered Indigenous peoples who had no cultural and political achievements to speak of.

Trigger’s book is particularly effective in this regard (and has informed my earlier discussion). Although he may have referred to the Wendat as Huron, as was common at the time, Trigger’s achievement was not lost on the Wendat themselves, who made him an honorary member. His description of the Wendat confederacy, to take but one example, remains thought-provoking decades after it was written. Beginning in the twelfth century C.E., the confederacy afforded its subjects a degree of input into political affairs that would remain unknown in Europe until after the French Revolution. It granted member nations significant local autonomy and sought to govern by consensus as much as possible. Ironically, after centuries of condescension toward Indigenous peoples on the part of French traders and missionaries, France today is part of the European Union, a political body that also employs a norm of seeking consensus among autonomous nations. In this way, modern Europeans follow political procedures similar to those that the Wendat and Haudenosaunee pioneered centuries ago.

Georges Sioui is Wendat (and the first Indigenous person in Canada known to have obtained a Ph.D. in history). He builds on Trigger’s account, which he often cites with approval, by drawing on Wendat oral tradition. The Wendat and Haudenosaunee, he notes, never went to war to gain territory or in the name of religion. Rather than seek the total destruction of their enemy, the immediate purpose of many raids was to capture members of the rival community, who would be assimilated into the captors’ culture to replace family members lost to disease or war (hence the expectation in The Orenda, which the Haudenosaunee girl struggles with, that she become Wendat.)

Wendat and Haudenosaunee combatants also followed a strict honor code, in keeping with what was arguably the ultimate function of their conflicts, providing an opportunity for male warriors to gain status through acts of bravery. “It’s a game we play with one another,” the Wendat narrator reflects in a passage from The Orenda that recalls both Trigger and Sioui, “a chance for the young men to prove themselves and collect a little bounty.” Sioui, who is thanked in Boyden’s acknowledgements for reading the manuscript, provided a blurb praising The Orenda for allowing readers “to see through Native eyes the immense human tragedies that attended the birth of North American nation-states.”

In addition to generating interest in non-fiction about the Wendat, The Orenda may also generate interest in fictional stories of colonial contact. In my own case, reading Boyden awakened an interest in contact novels set in Canada, such as The Beothuk Saga (2000), by Bernard Assiniwi, and far beyond, as with Things Fall Apart (1958), by Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe. Like Boyden, these authors imaginatively reconstructed Indigenous life, among the Beothuk of what is now Newfoundland and the Ibo in what would become Nigeria, in the lead-up to contact with Europeans. Assiniwi is a Cree author and Achebe is Ibo (now often rendered as Igbo). That The Orenda could generate interest in their work makes Boyden not their enemy, but their servant.

The Orenda contains scenes of gruesome violence. After the Wendat capture some Haudenosaunee warriors, they slash the captives’ torsos with knives and clamshells, and jab burning sticks into their legs and buttocks. The prisoners are then brought inside a longhouse, where they are subject to ritualized torture. The purpose of the ritual, which lasts until dawn, is to make the victims cry out for mercy. For this reason, they are not allowed to pass out. When the prisoners appear on the verge of going unconscious, the Wendat villagers stop the torture to dress their wounds, and start the process again.

The victims can die as heroes if, rather than break down, they go to their graves while singing their death songs, which they have memorized in anticipation of falling into enemy hands. The Wendat work hard to prevent this with beatings, bone-breaking, and burning. At the end of the book, the Jesuit experiences an even more horrifying fate: His last memory is of a Haudenosaunee warrior cutting open his chest and pulling out his heart.

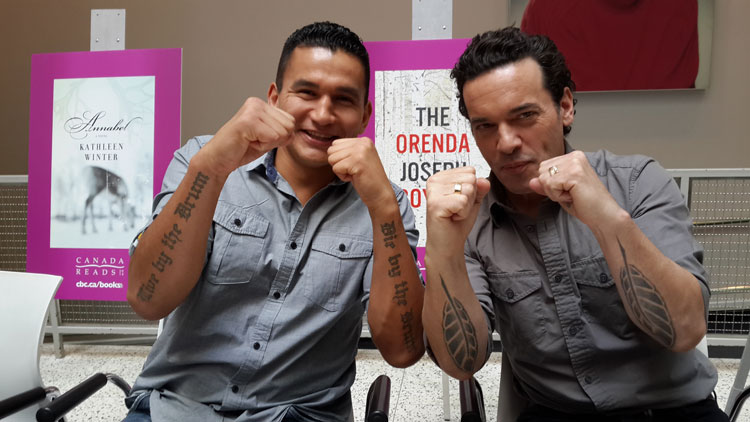

The excruciating detail with which these scenes are narrated has divided critics, including Indigenous ones. This was evident when The Orenda was chosen for the 2014 edition of Canada Reads, during which the novel was championed by Wab Kinew, who was just elected as Canada’s first Indigenous provincial premier. After another panelist said that the book depicted torture as pornography, Kinew, who is a member of the Onigaming First Nation, replied that “the violence is key to understanding the message”:

If we look at the violence, the torture scenes in the book, from a Western perspective, then of course we’re going to arrive at the same conclusions that people did 400 years ago, that these people are savage…These people are engaged in a relationship with each other. And if you read historic texts from 400 years ago, the warriors from one nation would be upset if the warriors from another nation did not scalp, did not torture, their brethren. And the reason for that was that was your chance to prove your honour, and your dignity, one last time before you passed on to the spirit world.

Kinew’s positive view of the book stood in noticeable contrast to that of Hayden King, the director of the Yellowhead Institute at Toronto Metropolitan University. King, who is Anishinaabe, wrote a scathing review of The Orenda that condemned its depiction of violence. According to King, the book was “a comforting narrative for Canadians about the emergence of Canada: Indian savages, do-good Jesuits and the inevitability (even desirability) of colonization.”

King also drew attention to a genuinely puzzling feature of the novel. The Orenda is divided into sections, each of which is introduced by a short, enigmatic speech that appears to be spoken by beings from Wendat mythology. Part of one such mythic narrative states, “It’s unfair to blame only the crows, yes? It’s our obligation to accept our responsibility in the whole affair. And so we watched as the adventure unfolded, and we prayed to Aataentsic, Sky Woman, who sits by the fire right beside us, to intervene.”

King takes passages such as this to mean that part of the reason colonialism occurred was “because of the selfishness, arrogance and short-sightedness of the Huron.” Boyden’s book, in short, places part of the blame for colonialism on its victims.

King says that the novel portrays violence and torture as “the exclusive domain of the Indians.” But this overlooks the scenes of European violence that show it to involve its own special forms of cruelty, which the Indigenous characters condemn. Indeed, the narrative repeatedly juxtaposes Indigenous and European violence, including in the scenes involving the attempted rape and its punishment, in ways that undermine the idea that European violence was nonexistent or somehow better.

Crucifixes also play a symbolic role throughout the story. At one point the headman refers to the Jesuit and the “splayed and tortured man he always wears on his neck,” suggesting that seventeenth-century Catholicism fetishized torture in its own way. If the European acts of violence in the book have not generated outcry, this may only be because we are already so familiar with them.

Yet even if the depictions of Indigenous torture are historically accurate, there is an aspect of Boyden’s rendering that remains disturbing. After 9/11, Western governments were revealed to employ or condone torture as an interrogation tool. One of the points that is often made in the torture debate concerns the falsehood of the popular image, found in countless movies and TV shows, of the masculine hero who is able to withstand torture without breaking down. Human beings who can resist torture, if they exist at all, are rare. The main function of the myth of the recalcitrant hero is to add to the burden of torture’s victims by making them feel guilty for “confessing” whatever is necessary to make the torture stop. The fact that not just some but all of the book’s torture victims, Indigenous and European alike, last hours or even days without breaking is a form of propaganda infecting Boyden’s account.

This shortcoming is not noted by King, whose critique instead takes a strange yet revealing turn by endorsing Margaret Atwood’s venerable notion of survival as the central concept of Canadian literature. King draws attention to the fact that, in outlining her theory, Atwood cited literature about the early Jesuit missionary Jean de Brébeuf, whom Boyden’s Jesuit resembles. As Atwood wrote of her survival trope, “for early explorers and settlers, it meant bare survival in the face of ‘hostile’ elements and/or natives.” For King, this is the key that unlocks The Orenda.

“Atwood even cites literature about Brébeuf as an example of Canadian survivance,” King writes. “So The Orenda reinforces who and what Canadians believe they are. [The Jesuit] tells a story they know and can identify with…He becomes the protagonist, the doomed hero that reinforces colonial myths of savagery on the one hand, and salvation, on the other—‘survival in the face of hostile Natives.’ ”

My own view is that, notwithstanding the popularity of Atwood’s thesis, the idea of survival never shed much light on Canadian literature. And by the time King’s article appeared, in 2014, few readers familiar with Canadian writing still took the survival theory as a helpful starting place. But even if we take Atwood’s framework on its own terms, The Orenda does not fit her pattern. Atwood does discuss “literature about Brébeuf,” but aside from a brief mention of his appearance in a Leonard Cohen novel, her discussion consists of an analysis of a single E. J. Pratt poem about the famous Jesuit. Atwood quotes with approval Northrop Frye’s remark, written four centuries after Hobbes, that in Pratt’s poem, “Indians represent humanity in the state of Nature and are agents of its unconscious barbarity.” As we have seen, The Orenda is a literary repudiation of this undying falsehood. It is as if, for King, the possibility that Boyden wrote an anti-colonial novel simply cannot be true.

This still leaves us with the sky people’s strange remarks on who was responsible for colonialism. After King’s article appeared, Boyden told an interviewer that the sky people should in fact be read as saying that Indigenous people deserve some blame for their own colonization (“not nearly as much blame as the colonizers, of course,” he was quick to add). Boyden here joins the long list of authors who make wayward interpreters of their own work. A more attractive possibility is suggested by one of Boyden’s sources, Bruce Trigger, who calls into question the idea that Wendat mythical figures embody the characteristics of Wendat (or any other) people.

“Among the Huron, men committed most of the real and symbolic acts of violence,” Trigger wrote, referring to practices such as hunting and war. “Women were associated with life-giving pursuits: bearing children, growing crops and caring for the home.” Despite this familiar division, Aataentsic is a violent and malevolent female figure, while her grandson Iouskeha is a male nurturer. “It is possible that by conferring certain human characteristics on mythical figures of the opposite sex, these myths aimed at compensating both sexes for the psychological limitations of the roles assigned to them in real life,” Trigger suggested.

Trigger’s observation about the sky people’s gender roles should make us pause before assuming that any of their attributes, whether related to gender or anything else, are neatly transferrable onto the Wendat. What if, by taking on responsibility for colonialism, they actually contradict the idea that their Wendat subjects are somehow to blame? Such a reading is more in keeping with the compensation through reversal that Trigger highlights in the case of gender. It is much more consistent with the novel’s grim depiction of the violence and plagues caused by colonialism. Indeed, by including sections narrated by Wendat religious figures and none by Christian ones, the novel subtly suggests that traditional Wendat beliefs were truer to reality than European religion.

The disagreement between Kinew and King over The Orenda may reflect a deeper disagreement among Indigenous intellectuals over Canada’s goal of making amends for the atrocities it inflicted on Indigenous people. In introducing The Orenda on Canada Reads, Kinew said the book “gives voice to the Indigenous so we can have a new conversation. Without that, no truth, no reconciliation.” Kinew is one of the most prominent Indigenous voices in favor of the project of reconciliation that the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada called for in its 2015 final report. Kinew is now Canada’s most prominent Indigenous politician. His willingness to seek office and lead a political party is consistent with his support for reconciliation. Accepting that Canada can make amends with Indigenous people after all presupposes that Canada’s political institutions are at least decent enough to deliver some measure of restorative justice.

King, for his part, may be the most prominent Indigenous skeptic of reconciliation. His journalism in national newspapers and magazines often questions whether reconciliation, at least as normally understood, can ever succeed. This attitude was on display in his response to a 2018 speech that had been given by Jody Wilson-Raybould, then Justin Trudeau’s Justice Minister, to fellow Indigenous leaders in British Columbia. In that speech, she criticized Indigenous thinkers who, “in the name of upholding Indigenous rights, critically oppose almost any effort to [create] change [within the Canadian constitutional framework].” King retorted that “the heretics have ample evidence of corrupt institutions on their side.”

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/GJ6KIVDW5VBG3MRJSPEAUSD5GA.jpg)

It is unsurprising that King would have sympathy for reconciliation “heretics.” Three years prior to Wilson-Raybould’s speech, King coauthored a thought-provoking essay with criminologist Shiri Pasternak that is something of a manifesto for the pro-Indigenous, anti-reconciliation stance. King and his coauthor were cool toward the political and legal changes that reconciliation is often associated with. They characterized “voting in or out unsupportive and delinquent governments, and using the courts to achieve justice as all reinforcing an unthreatening politics of charity: sophisticated and pragmatic, but also relatively benign.” Against this, they favor a different approach, one that takes seriously calls by Indigenous thinkers for “disengagement from and alternatives to state forms of recognition and reconciliation.”

The central problem with King’s view was well captured by Wilson-Raybould in her aforementioned speech criticizing Indigenous reconciliation skeptics. “These voices, paradoxically, sometimes end up reinforcing the same outcome—inaction—that those who oppose rights recognition for Indigenous peoples and reconciliation pursue.” And if Boyden’s identity matters, then by the same logic, when it comes to elections, it is worth celebrating the political ascent of candidates such as Kinew, Manitoba’s newly elected premier.

The Orenda takes the reader back to some of Indigenous peoples’ first encounters with what would eventually become Canada. For someone open to the possibility of reconciliation, it can thus be read as an origin story—one that naturally motivates readers to consider, and perhaps work to correct, Canada’s historical legacy. But because the novel, as a historical work, does not suggest any view, pro or con, regarding contemporary efforts at reconciliation, it does not provide any succour to readers, such as King, who’ve already decided that reconciliation is destined for failure. Indeed, if one takes the main lesson of Canadian history to be that Canada will always be too infested with colonialism to make reconciliation possible, then the novel may seem too gentle on Canada, despite all the violence and plagues it depicts.

By falsely characterizing The Orenda as a colonialist work, King does Boyden an injustice. He also sends an unhelpful message regarding literary progress. Novels of colonial contact have been around for a long time. Older versions of the genre really were colonialist. (Heart of Darkness, for example, gives African characters practically no speaking time.) If we are not going to distinguish an author such as Boyden from these predecessors, then novelists who write contact stories might as well produce colonialist propaganda, as there is no longer any point in trying to do otherwise.

In exposing Boyden, neither Jorge Barrero nor Robert Jago suggested that Boyden’s novels should no longer be read. Barrero’s news story offered no comment on Boyden’s fiction. Jago, for his part, emphasized that his concern was not with the very idea of a non-native writer telling native stories. He cited the example of a white journalist who spent time on the reserve where Jago grew up before writing about members of Jago’s family who had attended residential schools. (“I don’t mind him telling their story. He put in the time with the community, earned trust,” Jago wrote, “and everyone knows it’s an outsider’s voice.”) Calls to no longer teach or read Boyden, whom everyone now knows is an outsider, only occurred later, after less careful critics began to pile on Boyden on Twitter and call for his cancellation.

What does it mean to cancel a person? Recent years have seen heightened sensitivity to language. Media and other organizations, for example, have stopped using the term “illegal immigrant” on the grounds, surely reasonable, that illegality should apply only to actions, not people. Online critics who denounced Boyden following the exposé about his background showed no concern for such niceties. The hashtag #CancelBoyden suggested the problem was not Boyden’s actions, but his being.

After his cancellation, Boyden was divorced from his wife and moved from New Orleans to the Georgian Bay region of Ontario, where he lived with a new partner (who is Indigenous) and their two children. In a 2019 article in Georgian Bay Today, Boyden wrote, “I’ve faced some hard days the last years. Hard enough that for a frightening stretch…I no longer believed I cared enough to live.” This outcome should be recalled the next time social media calls on us to cancel a human being.

But this essay is not called “Joseph Boyden: A Defense.” No estimation of Boyden’s fiction changes the fact that he was wrong to present himself as Indigenous. The Indigenous people in Boyden’s historical novels are connected by lines of descent to people alive today. Efforts to determine how much Canada has changed from a colonialist society to one that shows equal respect to native people become impossible when we cannot identify who grew up in Canada as an Indigenous person and to what degree society may still put obstacles in their way.

This consideration will apply when any white person falsely claims a different racial or cultural identity. There is however a further reason for concern in cases of Indigenous identity fraud: This particular misrepresentation has long been all too common. In 1992, Bill Cross, a cofounder of the American Indian and Alaska Native Professors Association, was asked to estimate how many of the 1,500 American academics who presented themselves as Indigenous were genuine. “We’re looking realistically at one third of those being Indians,” he replied. This kind of misrepresentation also has made headlines in the arts: Just last month, famed Canadian singer-songwriter Buffy Sainte-Marie was accused of fraudulently presenting herself as Indigenous for more than half a century (and, as with Boyden, of having presented conflicting accounts of her family history).

Sociologists now use the term “self-indigenization” to describe this trend. The word was coined by Darryl Leroux, a sociologist at St. Mary’s University in Halifax. His central example is the rise of so-called “Eastern Métis” groups: organizations composed of white Canadians and Americans who claim Indigenous identities. Some Eastern Métis leaders have even had histories of opposing Indigenous rights or belonging to white supremacist organizations, but the practice is of concern even when practitioners do not have such links. Self-indigenizers often seek to exercise hunting rights and other prerogatives reserved for Indigenous people.

Dubious claims to Indigenous identity are frequently justified through “a tenuous genealogical relation with a long-ago [Indigenous] ancestor,” Leroux notes. This relation is often presented as being connected to an oral tradition of Indigenous identification within the self-indigenizer’s family. Boyden’s 2016 description of himself and other family members as “keepers of a number of oral histories passed down to us from previous generations that speak both to our European and to our Indigenous roots” fits the pattern Leroux and others have sought to counter.

The myth of the disappearing Indian is a recurring historical trope that characterizes Indigenous people and their culture as long gone, a convenient belief in societies with unresolved land claims. Cases such as Boyden’s suggest there is a second myth, that of the appearing Indian, which Indigenous people must now also contend with. We should recognize the pernicious ways Boyden embodied this myth. But we should also recognize that the full story of Boyden’s case cannot be summed up in a hashtag.

We need to form separate judgments about his biographical narrative and his literary ones. Because in matters of truth, a critical mind is like a confederacy. It can recognize autonomous domains of veracity and falsehood, and allow both to coexist.

This essay has been adapted, with permission, from the author’s newly published Sutherland House book, The Canadian Mind: Essays on Writers and Thinkers.