Indigenous History

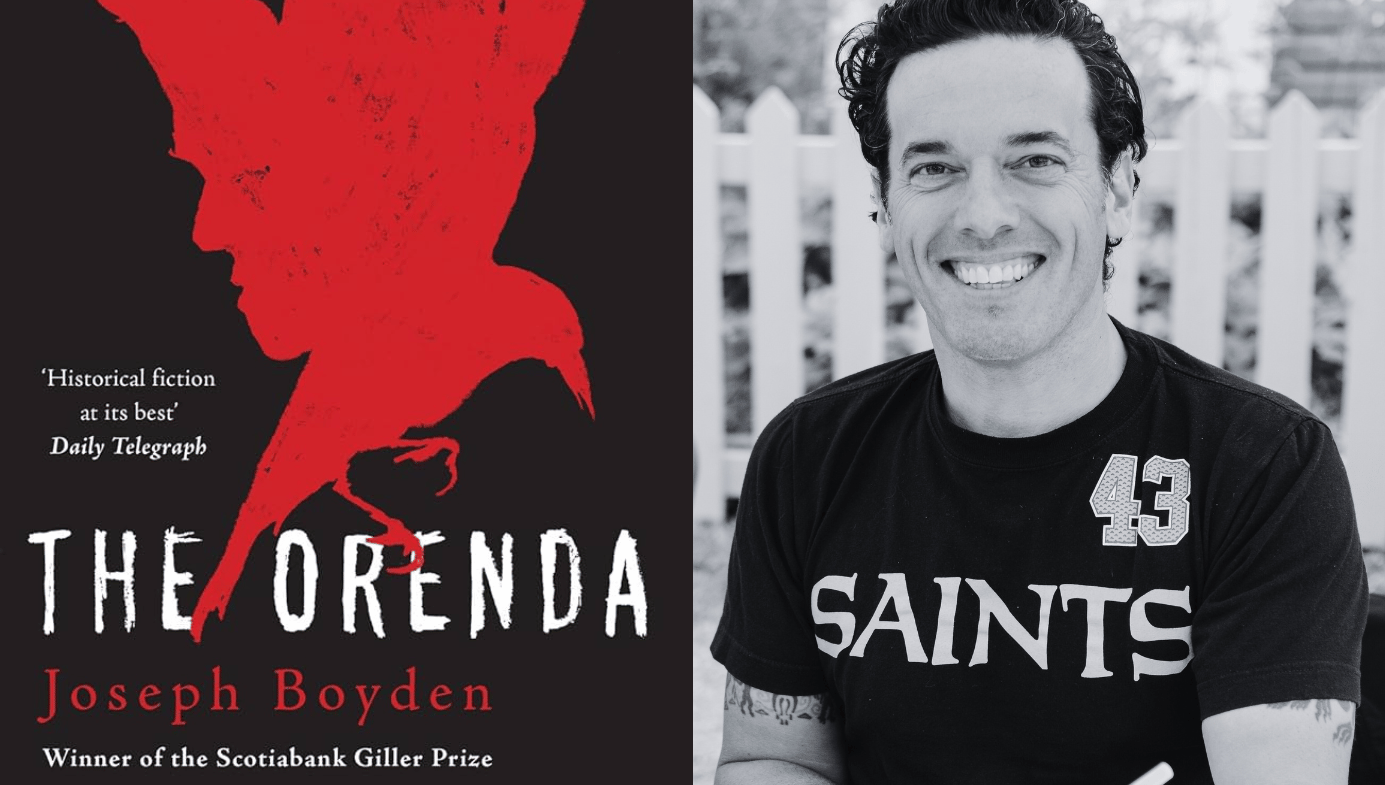

Joseph Boyden Isn’t Indigenous. But his Historical Fiction Is Still Worth Reading

The author’s widely celebrated 2013 novel, ‘The Orenda,’ helped educate Canadians about their country’s colonial roots. It shouldn’t be cast into literary oblivion just because Boyden misrepresented his ancestry.

Canadian novelist Joseph Boyden isn’t Indigenous. The truth came out in 2016, a few days before Christmas, when writer Robert Jago asked, in a series of tweets, “Is Joseph Boyden actually native?”

Even as Jago was tweeting, the Aboriginal People’s Television Network (APTN) was working on a story about Boyden. It soon appeared under the headline “Author Joseph Boyden’s shape-shifting Indigenous identity.” Reporter Jorge Barrera wrote that Boyden had for years “variously claimed his family’s roots extended to the Métis, Mi’kmaq, Ojibway and Nipmuc peoples.” Barrera drew attention to Jago’s tweets and cited genealogical research showing that Boyden’s changing claims of Indigenous ancestry, in addition to being inconsistent, were all false. By January 2017, critics on Twitter were using the hashtag #CancelBoyden to call for Boyden’s speaking invitations and other professional opportunities to be withdrawn. Successfully, it would turn out.

Boyden’s change in fortune was stark. In 2016, he was the respected author of Three Day Road and other acclaimed novels on Indigenous themes—which had won the Giller Prize and other major literary awards, and had transformed Boyden into an enthusiastic spokesperson for Indigenous concerns.

By 2017, however, Boyden’s name had become, as a report in a Toronto-based newspaper, the Globe and Mail, put it, “a byword for ethnic fraud and cultural appropriation.” In 2017, Boyden gave a few interviews and wrote a magazine article in which he tried, without success, to defend himself from accusations of identity fraud. Since then, Boyden has been little heard from. As of this writing, no further books have appeared under his name.

Some observers have suggested that this is no great loss, as Boyden’s writing now has little worth. This view was expressed during a 2017 panel discussion at the University of Alberta. Janice Williamson, a professor of English and film studies, said, “I am not going to teach Joseph Boyden [as an Indigenous author]. He takes up the space of Indigenous writers.” Fellow panelist Norma Dunning, then a PhD student in education, went further: “If I were you, I wouldn’t teach Boyden. Period.” Since then, views similar to Dunning’s have regularly appeared on social media. As David Gaertner, a professor in the First Nations and Indigenous Studies Program at the University of British Columbia, tweeted in 2020, “Joseph Boyden should not be on your syllabus unless you are teaching a course on fraudulence.”

Williamson was making the fair point that in classes on Indigenous writers, Boyden’s work no longer has a place. But the thought that Boyden should no longer be taught, period, or only as an example of fraudulence, suggests that the revelation of Boyden’s identity snuffs out whatever value his fiction possessed. In this way, the backlash against Boyden has gone too far. If the case that Boyden misrepresented his identity is overwhelming, the case that we should no longer read his novels rests on a confused and complacent understanding of what it is for a writer to “appropriate” material from a culture not their own. Particularly in the age of Indigenous reconciliation, we should be reluctant to cast aside such richly imagined work as Boyden’s famous 2013 novel, The Orenda—which pulses with anti-colonial energy.

The case against reading Boyden hinges on accusations of cultural appropriation. Bu that term has become amorphous through its application to everything from outsiders writing songs about minority cultures to Indigenous land being seized at gunpoint. Should all of these activities be condemned in the same breath? Or could there be value in a non-native writer depicting native experiences, so long as it is done in a careful and informed way?