So-Called Dark Ages

A Roman Trauma

In the fourth instalment of ‘The So-Called Dark Ages,’ podcaster Herbert Bushman describes the Visigothic sack of Rome in 410 C.E.

What follows is the fourth instalment of The So-Called Dark Ages, a serialized history of Late Antiquity, adapted from Herbert Bushman’s ongoing Dark Ages podcast.

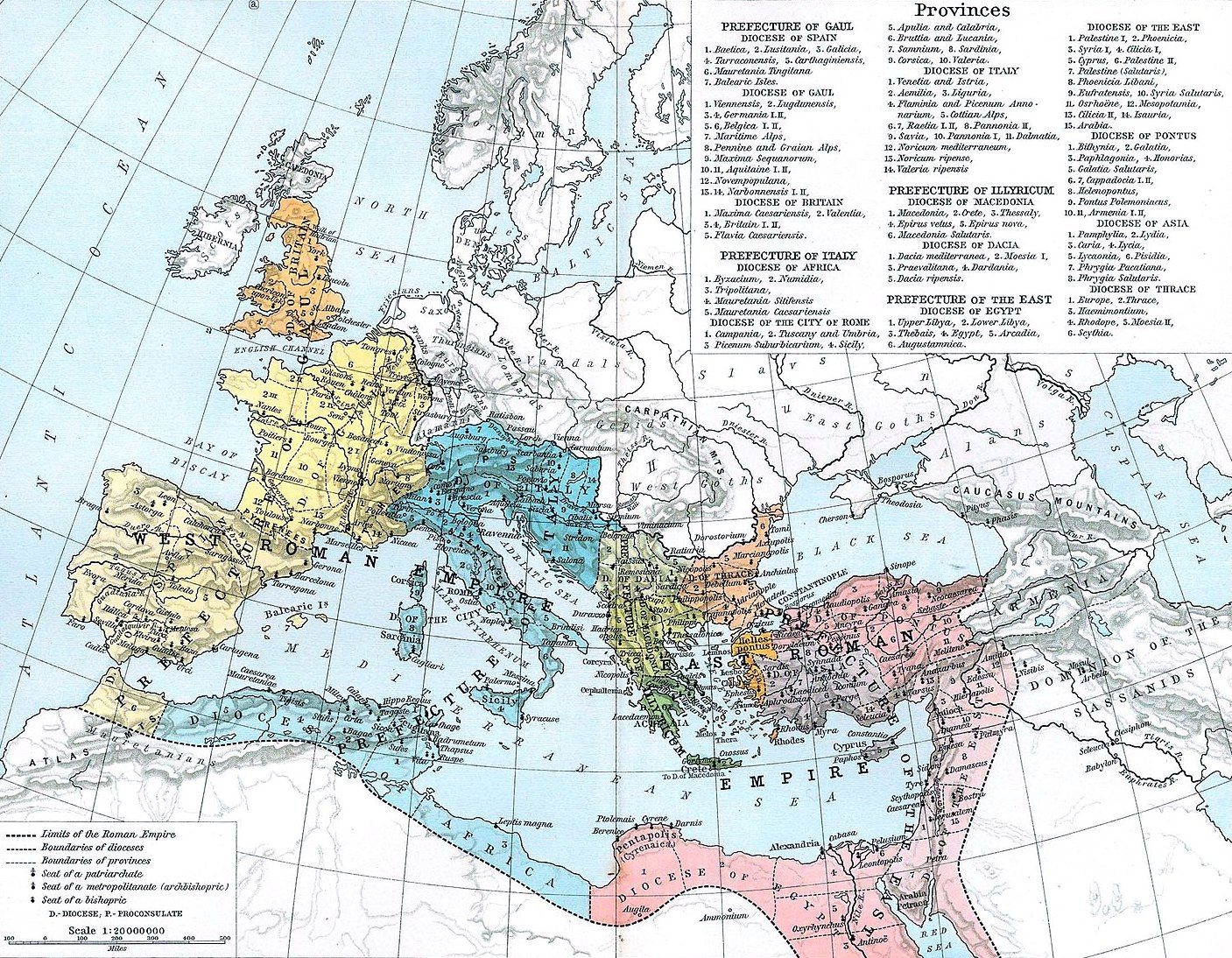

In our last instalment, we left off with the Western Roman Empire’s crumbling Rhine defenses under assault from west German tribes, whose members were now pouring across the border. Meanwhile, our Gothic hero (if that’s the right word)—Alaric, the first King of the Goths (King of the Visigoths technically, but that doesn’t have the same ring to it)—had assembled thousands of fighters in the Roman province of Noricum (roughly corresponding to modern Austria). These troops would not join the attack on the Rhine frontier, but instead would descend on northern Italy. Consistent with his usual pressure tactics, Alaric’s goal was to force the Emperor in the west, Honorius, to the bargaining table; whereupon, Alaric believed, he could secure land, gold, and provisions for his long-wandering people. Alaric had invaded (and looted) northern Italy previously, but had been forced to retreat. This time, his invasion would be more successful.

However, Alaric would not be dealing with Honorius, the 24-year-old Emperor who’d been installed on the throne as a child, and who’d been treated as a puppet ruler ever since. Rather, the Gothic leader would be facing the real power in the western half of the Empire—the military commander known to history as Stilicho.

Stilicho was as competent as Honorius was gormless—though also arrogant and ruthless. He was half-Vandal by birth, which was something his enemies brought up often. As previously discussed, he and Alaric had, by now, been circling each other in a heavily armed pas de deux for the better part of two decades. (I like to think they had a soldierly respect for one another, though I have no way to know.) Over time, they’d worked together so that the western Empire could assert control over Illyricum—a Roman province contested by the Empire’s eastern and western halves—before their relationship inevitably went sideways.

The ongoing Roman military disaster on the Rhine had actually been partly Alaric’s fault: In order to defend Italy from barbarian attacks (of which Alaric’s was just one), Stilicho had stripped the Rhine garrisons down to skeleton crews. That didn’t work, however: Pressed from behind by marauding Huns coming out of the east, the Germans shot past the Romans’ Rhine forts. In the absence of any effective military response from Ravenna—the western Roman capital from 402 C.E. onward—the Roman commander in Britannia, a common soldier who’d worked his way up the ranks, took things in hand and sailed down to Gaul in 407 C.E., now declaring himself Emperor Constantine III. Unfortunately, he completely abandoned Britannia in the process. And as things turned out, this abandonment was permanent: The Roman Emperor would never again bring Britain back under its control.

Alaric’s demands included formal Gothic possession of lands in Noricum, on top of the cash payment that he’d previously been promised by Stilicho during their negotiations regarding Illyricum. The Roman Senate was then having a modest revival in its powers as the authority of the Emperors waned. Many Senators were angry that Stilicho hadn’t finished Alaric off back in 402 C.E., after the Goths had spent months looting the estates of northern Italy. And so they were unenthusiastic about the idea of paying Alaric off this time around. But Stilicho talked them into it.

War wasn’t averted for long, however, because Stilicho’s longtime rivals at court took this opportunity to finally bring the man down. Ironically, Stilicho’s diligence as a military commander contributed to his downfall: Having become distracted by the need to prop up the disintegrating Empire, he’d let his grip loosen on the (puppet) Emperor Honorius, whose blessing was the basis for Stilicho’s political legitimacy.

A courtier named Olympius began muttering in Honorius’ ear, suggesting that Stilicho was planning to put his own son on the eastern Roman throne (mutterings that might have been true, in fact). Once that happened, Olympius asked, what would stop Stilicho from getting rid of Honorius?

As these rumours spread, an anti-Stilicho revolt took shape. Despite knowing what dark fate likely awaited him, Stilicho returned to Ravenna, where he was arrested and executed on August 22, 408, just nine days after the outbreak of the revolt.

The coup was a complete success for Olympius, but he wasn’t done. Stirred up by the anti-German sentiment that had helped bring down Stilicho, the new regime moved against German communities. In the turmoil that followed, local German populations in Italy were massacred by their neighbors. And by “local German populations,” I’m referring to the wives and children of the Germanic foederati troops serving in the Roman military. Whether this was planned or part of an unintended outbreak of anti-German hysteria isn’t clear. But whichever the case, all those German federate troops picked up their swords and shields and signed on with Alaric.

Just then, the new Imperial power-brokers discovered just how many geopolitical chainsaws Stilicho had been juggling in his desperate attempts to keep the western Roman empire together. There’s a valuable lesson here: Before overthrowing a rival, always make sure you actually want his or her job. (Also, lesson number two: don’t murder thousands of your soldiers’ wives and children and then expect to retain their loyalty.)

Olympius, like most men who engineer coups of this type, had a very high opinion of his ability to solve his predecessor’s problems. When envoys arrived from Alaric, offering to overlook the coup if the Romans would grant subsidies, hostages, and permission to settle in Roman lands, Olympius refused. And so it was that six weeks after Stilicho’s execution, Alaric invaded Italy again.

The Goths sacked the coastal Adriatic city of Rimini (which is now a high-rent vacation destination), and moved west through the countryside as if “going to a festival,” according to the historian Zosimus. Alaric clearly felt that he had nothing to fear from Stilicho’s successors. In this, he was entirely correct, reaching Rome unmolested in 408 C.E.

Rome was, by this time, no longer the capital of the western half of the Roman Empire. Military administration had moved to the more geographically convenient centers of Constantinople, Milan, Sirmium, and Triers; and the Emperor himself was now in Ravenna, on Italy’s Adriatic coast. But the lingering psychological and spiritual importance of Rome cannot be overstated. It had been seen as the center of all circles in the western world for many lifetimes; and was increasingly becoming the Empire’s spiritual center, as the Pope’s influence gradually expanded. It had been protected from foreign armies for eight centuries: The last time it had been sacked was in 390 B.C., by a Gallic chieftain named Brennus.

Alaric’s siege triggered a crisis of faith within the walls of Rome. Christianity had been the Empire’s favored creed for more than a generation, but there were still plenty of old-school pagans in high places. Rome itself, despite its exalted status within Christendom, was something of a pagan stronghold, in fact, especially when it came to members of the conservative Senate.

Sacrifices and traditional divination were banned, but the old temples remained open and many residents still used them to worship the old gods—though perhaps less openly than they once did. With Alaric camped outside the walls, pagan Senators wondered aloud why the Christians’ god would allow his people to be defeated by this barbarian nobody (ignoring the fact that Alaric himself was a Christian, albeit of the heretical Arian variety). The Senators’ calls for a resumption of sacrifices to Jupiter became so strident that Pope Innocent I conceded that such sacrifices could take place (though only in private).

It wasn’t just the Christian God who was failing Rome, but also Honorius and his new military commander, Olympius. There simply weren’t enough troops available to face Alaric now that Rome’s Gothic contingents had mutinied.

In the absence of leadership from Ravenna, it was the Emperor’s impressive sister, Galla Placidia, who became a symbol of Imperial leadership in Rome. In every way, Placidia was the opposite of her hapless brother. And she will be with us for a while going forward.

As December 408 C.E. arrived, Alaric took control of Rome’s logistical lifeline, the Tiber River, and starvation began to set in among the city’s residents. Further resistance seemed useless, and so the Senate sent an embassy to Alaric. The Gothic king named his price, which was all the movable goods and provisions left in the city.

The shocked Senators asked: What would that leave for the people?

“Their lives,” was Alaric's terse answer.

The Senators tried talking tough, pointing out that every Roman citizen had been trained to fight in defense of the city, and so even if the Visigoths managed to break in, they would be vastly outnumbered by armed residents. This was an absurd claim, and it's hard to imagine Alaric receiving this threat with a straight face. “Thicker grass,” he reportedly replied, “is easier to cut.”

(There aren’t many direct quotes attributed to Alaric. But the ones that do come down to us have a pithy, no-nonsense quality that stands out starkly against the overwrought style of late antiquity. However, the odds are good that memorable lines such as those quoted above were invented by chroniclers.)

The Romans agreed to ransom their city. The price included 5,000 pounds of gold and 30,000 pounds of silver, along with an array of hides and silks, and 3,000 pounds of pepper. The value of the metal in the coins alone would be around US$170-million today. To gather all the required specie, pagan temples were stripped of their ornaments, and some of the idols melted down. It’s hard not to see a little bit of petty revenge there on the part of the city’s Christian leaders for the suggestion that this was all punishment for their impiety.

Alaric withdrew, loaded down with this treasure. But he still hadn’t solved the problem that had led to his invasion—a lack of a permanent homeland for his people. He withdrew only as far as Tuscany, where he would spend the winter while the Emperor and his lackeys thought things over. By now, the Gothic army had swollen to nearly 40,000 soldiers, with escaped slaves from Rome joining Alaric’s ranks.

Determined to fight on, the Romans brought over 6,000 soldiers from the eastern side of the Adriatic, so as to garrison Rome and hopefully prevent the humiliation of December from being repeated. It was a fine idea. But Honorius—or, more properly, Olympius—put an absolute clown in command of the operation.

That commander’s name was Valens—not to be confused with the fourth-century Roman Emperor of the same name. Valens chose to take the most direct possible route to Rome, even though that route led right through Visigoth-controlled territory. Thus did 6,000 Roman soldiers end up marching into combat against a Gothic force many times larger. Only about 100 of Valens’ men avoided death or capture.

Then the news got even worse for Rome: Alaric’s brother-in-law Ataulf had appeared out of the Julian Alps and was now marching down the Italian peninsula to join Alaric. Panicked, Honorius instructed Olympius to intercept this new threat. What exactly happened next is a bit confusing, because Olympius supposedly met Ataulf in battle near Pisa, and killed 1,000 Goths while losing only 17 of his own men. And yet history also records that Olympius was forced to retreat back to Ravenna after the battle—a result that’s hardly consistent with claims of a great Roman victory. The same might be said for the fact that Olympius then fell from power and had to scoot across the Adriatic to save his skin.

The man who took his place was a former Stilicho supporter named Jovius, a man who was prepared to talk with Alaric. During their meeting, the Visigothic king said that he wanted pretty much what he’d always wanted: land from Rome’s northern provinces and an annual tribute of gold and grain. Jovius forwarded Alaric’s requests to the Emperor, adding that if they also offered Alaric a command within Rome’s military, it might be possible to knock down the deal’s cost.

Honorius, the clod (no other word seems suitable), rebuffed the idea. What’s worse, he did so in insulting tones, a fact that Alaric did not appreciate when Honorius’ letter was read aloud during the next meeting between Jovius and Alaric.

Alaric was fully prepared for war—but hesitated when he heard that Honorius was recruiting a force of 10,000 Huns. At this point, the Gothic leader dropped his demands down to land in Noricum and as much grain as the Emperor felt like giving him. Honorius rejected this offer, too, so Alaric marched back to Rome to start a second siege, hoping to get inside the city before those feared Huns showed up. (In fact, the Huns never did arrive, as their deal with Rome had fallen apart before they’d even reached Imperial territory.)

The Gothic King was losing patience with the young Emperor, so he hit on a clever new idea. If this Emperor wouldn’t see reason, why not make a new one who would?

The Senate sent emissaries almost as soon as Alaric had reappeared near Rome, and were only too happy to help with Alaric’s scheme. A Senator named Priscus Attalus was served up to act as a new puppet Emperor. He then dutifully appointed Alaric and Ataulf to Roman offices. The usurpers then commandeered provisions from around Italy and sent out letters informing the provinces of the change in management.

And yet Honorius was still in Ravenna. He’d effectively been deposed, though his personal circumstances were largely unchanged.

During this period, Gaul and Britannia were effectively lost to Italian control. The governor of Africa, a Honorius loyalist named Heraclian, also rejected rule by Priscus Attalus and his Gothic managers. This was a significant problem for Rome since Africa was the main source of the city’s food supply. The problem got worse when a force sent by Attalus to fight Heraclian was wiped out as soon as it landed on the African coast, infuriating Alaric.

Alaric stripped Attalus of his Imperial regalia. He didn’t kill him, though, and so Attalus was left in an awkward spot. Having burned his bridges in Rome, he ended up tagging along with the Visigoths—one of the odder personal epilogues in the annals of Roman Emperors.

For his part, Alaric marched off toward Ravenna to talk with Honorius—who was now the Emperor again, by default. At first, their negotiations seemed to go well—until yet another new actor appeared and ruined everything. This was a Visigoth of the Amal dynasty named Sarus—someone whom I briefly name-dropped in a previous instalment, noting that he’d have a key role in later events. Sarus had become a commander in the regular Roman army under Stilicho, and may have had a personal grudge against Alaric dating to old intra-Gothic power struggles.

Whatever the reason, Sarus attacked Alaric’s camp outside of Ravenna. And while the attack seems to have done little damage to Alaric’s forces, it destroyed his trust in Honorius. Alaric couldn’t believe that the Emperor hadn’t been involved in orchestrating this maneuver. Alaric packed up and headed back to Rome.

On August 24, 410, his Visigoths entered the city. And this time, there would be no negotiated settlement. Some sources say that Alaric entered when the walls were breached, others that a small contingent was able to infiltrate the city and open the gates. Another story has it that the gates were opened by a disaffected slave or some other treacherous fifth columnist. All of these seem equally plausible to me.

The result was a humiliation and a trauma. Historians never tire of noting the comparative mildness of the Visigoths’ sack or Rome when set next to the horrors the Romans themselves often visited upon cities they’d defeated. This starts early, with the sixth-century historian Jordanes, of Gothic ancestry himself, noting that when the Goths entered the city, “by Alaric’s command they merely sacked it, rather than setting it on fire, as wild peoples usually do.”

Alaric, being a Christian, designated the basilicas of St. Peter and St. Paul as safe zones of refuge, and posted guards around them to ensure that any who fled there would be undisturbed. Burning was kept to a minimum: Archaeology shows that destruction by fire was mostly limited to a few buildings around the forum.

But a sacking is still a sacking. When we’re arguing that a sack is less brutal because fewer homes than usual were destroyed, we’re falling into the trap of forgetting what such experiences would have been like for those living through them. Though the basic infrastructure of Rome weathered the Gothic storm mostly untouched, all the atrocities that went along with pillage were present. Everything of conceivable value was carried off, including people who’d be sold into slavery.

There was no general slaughter, as might have been expected for a city that fell after a period of resistance, but the inhabitants certainly didn't know that would be the case when the pillaging started. And though the majority of residents may have escaped death, many were tortured until they revealed the location of their wealth. The three days the Visigoths spent in Rome were an eternity to those who lived through it. Especially the women.

Writing a few years after witnessing the sack personally, the British monk Pelagius described the calamity as follows: “Every house was then a scene of misery, and equally filled with grief and affliction. The slave and the man of quality were in the same circumstances, and everywhere the terror of death and slaughter were the same.”

Thousands of homeless and destitute refugees spread out across the Empire, carrying news of the disaster far and wide. Some found new homes, while others were robbed of what little they’d brought with them. Some were even sold into slavery by the leaders they went to for help. Reversal of fortune was a universal theme in the historical accounts. Saint Jerome put it this way: “Who would believe that Rome, built up by the conquest of the whole world, had collapsed, that the mother of nations would also become their tomb?”

The sack renewed debate between Pagan and Christian elements within the Empire. Pagans blamed the catastrophe on the abandonment of the old gods, and called for a renewal of Roman traditions. Saint Augustine of Hippo set out to counter that position, saying that the material city was meaningless in comparison to the spiritual city prepared by God for the faithful. The resulting book, The City of God, laid the groundwork for the medieval Catholic church (and remains a torment to freshman humanities students to this day).

Among the captives removed from Rome was the aforementioned Galla Placidia, the Emperor’s sister, and probably the greatest treasure the Visigoths found in the city. Placidia was one of a handful of powerful and interesting women produced by the Theodosian dynasty (as if in compensation for the line’s almost universally useless men). We’ll talk much more about her in future instalments.

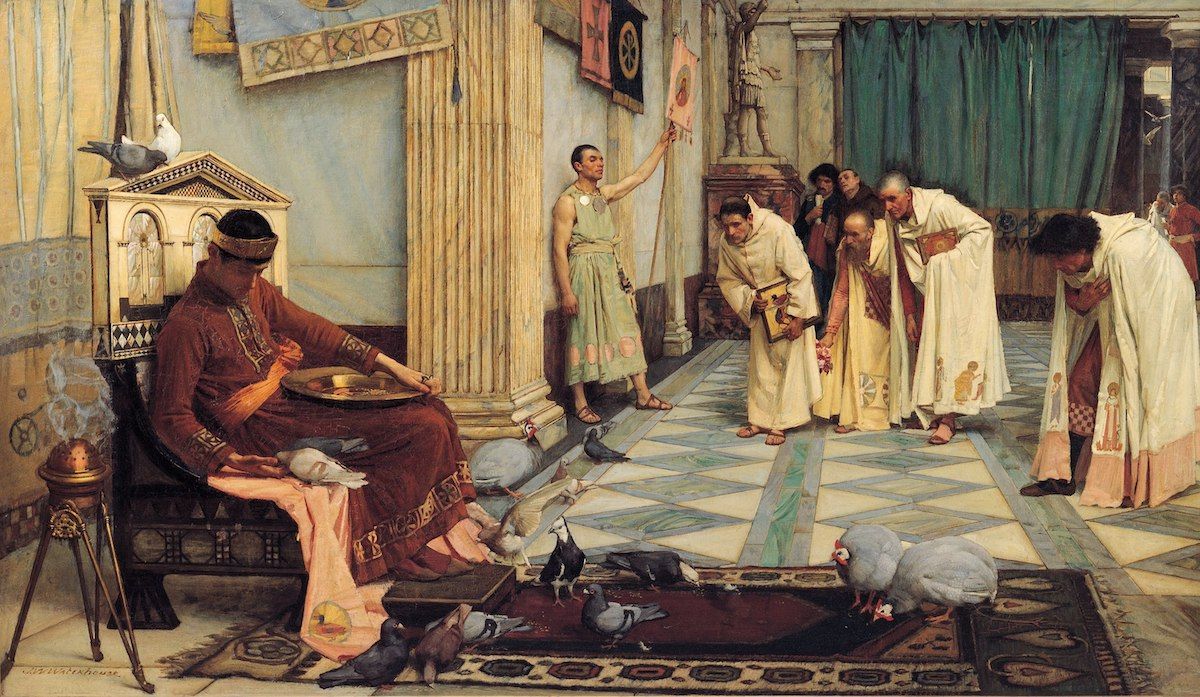

Speaking of useless men, there is a story—probably not true, but still worth relating—about Honorius’ response to Rome’s fall. It appears in one of Procopius’ histories, and goes like this:

At that time, they say that the Emperor Honorius in Ravenna received the message from one of the eunuchs, evidently a keeper of the poultry, that Rome had perished. And [the Emperor] cried out and said, ‘And yet it has just eaten from my hands!’ For he had a very large rooster, ‘Rome’ by name; and the eunuch, comprehending his words, said that it was the city of Rome which had perished at the hands of Alaric, and the Emperor, with a sigh of relief, answered quickly: ‘But I thought that my fowl Rome had perished.’ So great, they say, was the folly with which this emperor was possessed.

I have to wonder how Alaric felt as he watched his men storm through the ancient capital. No source I can find even speculates on the man’s state of mind. Notwithstanding the shock that the sack delivered to the rest of the Roman world, and the wealth that his men were busy loading onto wagons and carrying through the streets, the sack of Rome actually represented a failure for Alaric, and I can’t imagine that he wasn’t savvy enough to know that.

That comment to Rome’s Senators—about leaving the Romans with their lives back during the first siege—rings to me as a man playing a role, presenting the barbarian bellicosity that could get him what he wanted. He had invaded Italy, and roamed seemingly at will through the heart of what was still the greatest power in the world, and yet it had ultimately won him no lasting prize. Short-term pillage was the only tool he had left to provide for his people and ensure their loyalty. They were still, after all of this, without a home, without a place in the Empire. He would have to do better.

At no point did Alaric, or any of the men around him, even dream that they could found an independent kingdom, separate from the Roman empire. In spite of the evidence in front of his own eyes, to Alaric and everyone else, the Empire was a fact of life. For five centuries, it had been at the center of the European world. Changing that was inconceivable.

So Alaric turned south, intending to try crossing to Sicily, or perhaps Africa. Maybe without the arrogant and incompetent Attalus leading the charge, he could make some headway on the south side of the Mediterranean. Maybe there, in the breadbasket of the Empire, he could carve out a place for his Visigoths, and maybe even keep himself at their head.

But Alaric never got there. His attempts to cross the tricky Straits of Messina to Sicily failed. He fell ill with some kind of fever, and died while laying siege to Cosenza, way down toward the toe of Italy.

Legend famously has it that he was buried in the bed of the River Busento, with everyone involved in his burial then executed to keep the location a secret—though it’s hard to know if that’s true or not. (It’s a morbid motif that also shows up in stories about Attila the Hun and Genghis Khan.) Accounts of the great riches buried with Alaric have motivated treasure hunters ever since his death. But the Busento is a short river, and if anything were going to turn up, I feel like that would have happened by now.

Alaric was around 40 years old. He’d been King of the Visigoths for 15 years. And while he never secured the homeland he’d sought, he kept his people mostly together, and ensured that they would remain a force to be reckoned with inside the Empire that he’d humbled. It would fall to his successors to achieve his dream. And in time, they’d attain more power than Alaric himself could have ever imagined.