Evolutionary Biology

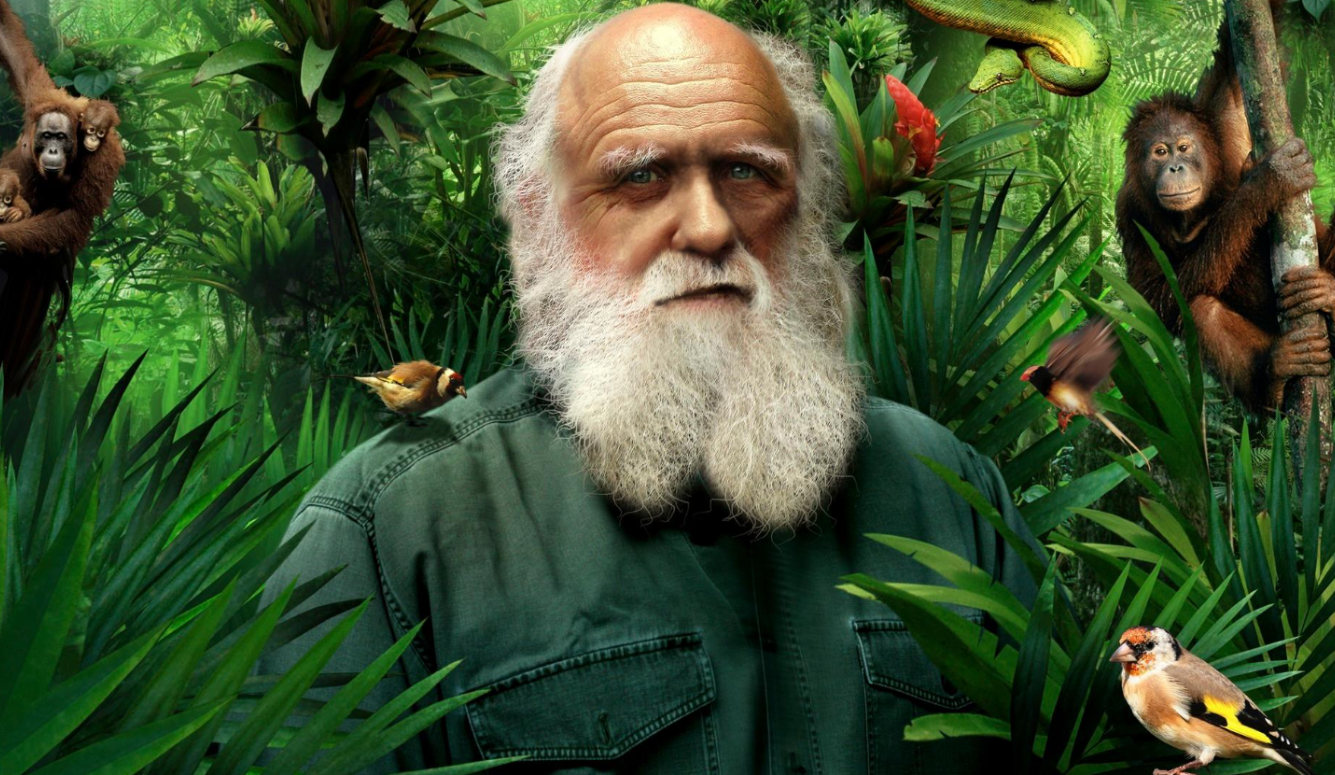

Charles Darwin: The Best Scientist-Writer of All Time

The Voyage of the Beagle is a literary masterpiece, as well as a scientific one.

Several years ago, the editors of an online science blog asked me who I considered the greater scientist: Charles Darwin or Albert Einstein.

Much to the surprise of my interlocutors, I voted for Charles Darwin. My argument was simple. Both Darwin and Einstein revolutionized their respective fields of biology and physics. Both made scientific discoveries that radically changed our perspective on humanity’s place in the cosmos and had broad societal impacts. But only Darwin combined the best characteristics of an observer and a theorist. His theory of evolution through natural selection was both indebted to his own comprehensive and meticulous observations and provided a beautiful theoretical understanding of the evolution of the vast diversity of life on Earth.

I have since discovered that I did Darwin a disservice by focusing only on the scientific basis of his brilliant breakthrough. In anticipation of my Origins Project Foundation’s upcoming Galapagos trip, I recently read large parts of Darwin’s first work, The Voyage of the Beagle (1839), and listened to the full recording of the abridged version, narrated by my friend and colleague Richard Dawkins. I could sense the delight in Richard’s voice as he recounted Darwin’s travels, and I found the convergence of the two men’s writing and speaking styles almost uncanny.

The book astonished me. I had expected arcane and dated descriptions of Darwin’s observations. I had not realized that his book is a literary masterpiece, as well as a scientific one. It is, on the one hand, a page-turner of an adventure story, relating frequent life-threatening encounters on land and sea, and on the other hand an awe-inspiring account of nature’s wonders. It is one of the most remarkable and uplifting stories of its type I have ever read. Time and again as I listened, I was overcome with admiration for Darwin as a writer, as well as a scientist.

Here is his description of his first encounter with the Brazilian rainforest:

Delight … is a weak term to express the feelings of a naturalist who, for the first time, has wandered by himself in a Brazilian forest. The elegance of the grasses, the novelty of the parasitical plants, the beauty of the flowers, the glossy green of the foliage, but above all the general luxuriance of the vegetation, filled me with admiration. A most paradoxical mixture of sound and silence pervades the shady parts of the wood. The noise from the insects is so loud, that it may be heard even in a vessel anchored several hundred yards from the shore; yet within the recesses of the forest a universal silence appears to reign. To a person fond of natural history, such a day as this brings with it a deeper pleasure than he can ever hope to experience again.

And here is his rumination on the soul-destroying brutality of slavery and the way in which the custom could quash the ethical integrity of even an otherwise moral man:

While staying at this estate, I was very nearly being an eye-witness to one of those atrocious acts which can only take place in a slave country. Owing to a quarrel and a lawsuit, the owner was on the point of taking all the women and children from the male slaves, and selling them separately at the public auction at Rio. Interest, and not any feeling of compassion, prevented this act. Indeed, I do not believe the inhumanity of separating thirty families, who had lived together for many years, even occurred to the owner. Yet I will pledge myself, that in humanity and good feeling he was superior to the common run of men. It may be said there exists no limit to the blindness of interest and selfish habit.

His enthusiasm is infectious, and his fascination with biological minutiae and patient willingness to experiment are unparalleled—even when he is studying slugs:

During the remainder of my stay at Rio, I resided in a cottage at Botafogo Bay. It was impossible to wish for anything more delightful than thus to spend some weeks in so magnificent a country. In England any person fond of natural history enjoys in his walks a great advantage, by always having something to attract his attention; but in these fertile climates, teeming with life, the attractions are so numerous, that he is scarcely able to walk at all.

The few observations which I was enabled to make were almost exclusively confined to the invertebrate animals. The existence of a division of the genus Planaria, which inhabits the dry land, interested me much. These animals are of so simple a structure, that Cuvier has arranged them with the intestinal worms, though never found within the bodies of other animals. Numerous species inhabit both salt and fresh water; but those to which I allude were found, even in the drier parts of the forest, beneath logs of rotten wood, on which I believe they feed. In general form they resemble little slugs, but are very much narrower in proportion, and several of the species are beautifully coloured with longitudinal stripes. Their structure is very simple: near the middle of the under or crawling surface there are two small transverse slits, from the anterior one of which a funnel-shaped and highly irritable mouth can be protruded. For some time after the rest of the animal was completely dead from the effects of salt water or any other cause, this organ still retained its vitality.

I found no less than twelve different species of terrestrial Planariae in different parts of the southern hemisphere. Some specimens which I obtained at Van Dieman's Land, I kept alive for nearly two months, feeding them on rotten wood. Having cut one of them transversely into two nearly equal parts, in the course of a fortnight both had the shape of perfect animals. I had, however, so divided the body, that one of the halves contained both the inferior orifices, and the other, in consequence, none. In the course of twenty-five days from the operation, the more perfect half could not have been distinguished from any other specimen. The other had increased much in size; and towards its posterior end, a clear space was formed in the parenchymatous mass, in which a rudimentary cup-shaped mouth could clearly be distinguished; on the under surface, however, no corresponding slit was yet open. If the increased heat of the weather, as we approached the equator, had not destroyed all the individuals, there can be no doubt that this last step would have completed its structure. Although so well-known an experiment, it was interesting to watch the gradual production of every essential organ, out of the simple extremity of another animal. It is extremely difficult to preserve these Planariae; as soon as the cessation of life allows the ordinary laws of change to act, their entire bodies become soft and fluid, with a rapidity which I have never seen equalled.

I was especially eager to read his account of the Beagle’s arrival at the Galapagos archipelago—which is one of the most coveted naturalist destinations in the world today because Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection arose, in large part, from observations he made of the flora and fauna of those isolated islands.

If you have ever been to the Galapagos Islands, you will know that their geological features are perhaps even more striking than their wealth of flora and fauna. Darwin’s interest and expertise as a geologist are evident throughout The Voyage. It was the geology of the Galapagos that first sparked his interest:

This archipelago consists of ten principal islands, of which five exceed the others in size. They are situated under the Equator, and between five and six hundred miles westward of the coast of America. They are all formed of volcanic rocks; a few fragments of granite curiously glazed and altered by the heat, can hardly be considered as an exception. Some of the craters, surmounting the larger islands, are of immense size, and they rise to a height of between three and four thousand feet. Their flanks are studded by innumerable smaller orifices. I scarcely hesitate to affirm, that there must be in the whole archipelago at least two thousand craters. These consist either of lava or scoriae, or of finely-stratified, sandstone-like tuff. Most of the latter are beautifully symmetrical; they owe their origin to eruptions of volcanic mud without any lava: it is a remarkable circumstance that every one of the twenty-eight tuff-craters which were examined, had their southern sides either much lower than the other sides, or quite broken down and removed. As all these craters apparently have been formed when standing in the sea, and as the waves from the trade wind and the swell from the open Pacific here unite their forces on the southern coasts of all the islands, this singular uniformity in the broken state of the craters, composed of the soft and yielding tuff, is easily explained.

It is impossible not to see in this section the germination of one of the most important biological scientific developments in human history: Darwin’s theory of evolution. The spark that lit his intellectual fire leaps off the page when he first muses about the surprising biological history of the islands:

The natural history of these islands is eminently curious, and well deserves attention. Most of the organic productions are aboriginal creations, found nowhere else; there is even a difference between the inhabitants of the different islands; yet all show a marked relationship with those of America, though separated from that continent by an open space of ocean, between 500 and 600 miles in width. The archipelago is a little world within itself, or rather a satellite attached to America, whence it has derived a few stray colonists, and has received the general character of its indigenous productions. Considering the small size of the islands, we feel the more astonished at the number of their aboriginal beings, and at their confined range. Seeing every height crowned with its crater, and the boundaries of most of the lava-streams still distinct, we are led to believe that within a period geologically recent the unbroken ocean was here spread out. Hence, both in space and time, we seem to be brought somewhat near to that great fact—that mystery of mysteries—the first appearance of new beings on this earth.

It would not remain a mystery for long, thanks to Darwin.

The heroic and beautiful tale of his travels as a young man, before his fame was secured, is mature, painstaking, and lyrical, all at the same time. I previously regarded Galileo Galilei as the prototypical great scientist/writer. His 1632 Dialogue Concerning the Two World Systems is a wonder of logic, simplicity, and humor laced with sarcasm. I have always required that my introductory physics students read his work, reasoning that if they can slog through James Joyce’s Ulysses, the Dialogues should be a breeze—and they are every bit as good a work of literature. But Darwin’s writing surpasses even Galileo’s. My admiration for him is unbounded.

I will return to the Galapagos for the third time next year, and this time I will go with my eyes opened to new wonders. One of the reasons I became a theoretical physicist is that I have a poor eye for detail, especially biological and geological detail. Part of this is due, I suspect, to my color blindness, which makes differentiating such details difficult. But part of it is caused by my general unwillingness to slow down and take the time to make the kinds of observations that turn the seemingly mundane into the profound. Inspired by Darwin’s account, I plan to focus on everything I see with a new intensity, and to try and share his sense of fascination. In so doing, I hope to be inspired anew by both the wonder of the natural world, and the intellectual contributions of the man who ended one of the most important scientific books ever written with one of the most memorable closing passages I have ever read:

Thus, from the war of nature, from famine and death, the most exalted object of which we are capable of conceiving, namely, the production of the higher animals, directly follows. There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.