philosophy

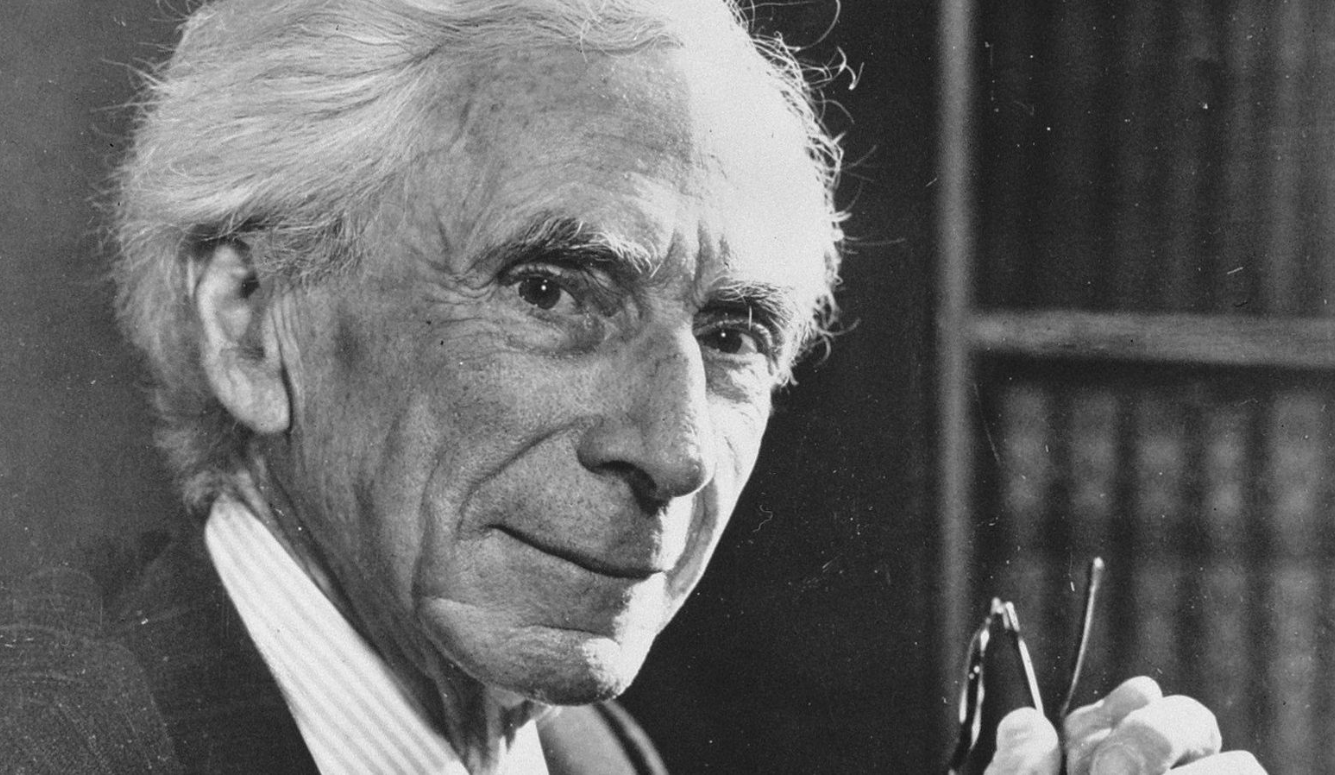

The Cancellation of Bertrand Russell

Eight decades later, the issues raised by the Russell case—the rights to free speech and academic freedom—have still not been settled.

Bertrand Russell is well known as a philosopher and mathematician. But few know that during his lifetime, he was cancelled—to use the contemporary term—by the New York judiciary and by mid-twentieth-century religious conservatives. Both those conservatives today who seek to ban books and regulate curricula and those progressives who wish to censor everyone who disagrees with them would do well to reflect on the Bertrand Russell case.

In February 1940, Russell was appointed Professor of Philosophy at the College of the City of New York by unanimous vote of the Board of Higher Education of New York City. (He was assigned to teach three courses with unwieldy names: logic and its relation to science, mathematics, and philosophy; problems in the foundations of mathematics; and relations of the pure to applied sciences and the reciprocal influence of metaphysics and scientific theories.) But within scarcely a month, Justice John E. McGeehan of the New York Supreme Court (in New York State, this is the designation of the trial court) ordered the Board to revoke Russell’s appointment, ruling that the appointment “adversely affects public health, safety, and morals” and would “aid, abet, or encourage … conduct tending to a violation of penal law.” A year later, in 1941, philosopher and educational reformer John Dewey noted that, although the Russell case was closed, “the issue underlying it is no more settled than the Dred Scott case [which ruled that no African American could ever become a US citizen] settled the slavery issue.” Eight decades later, the issues raised by the Russell case—the rights to free speech and academic freedom—have still not been settled.

Russell was born into a prominent aristocratic family in 1872, in the Welsh village of Trellech. He studied first mathematics and later philosophy at Cambridge University. In June 1916, he was fined for writing a pamphlet outlining his pacifist views and in February 1918, he was sentenced to six months’ imprisonment under the 1914 Defence of the Realm Act for publicly lecturing in favor of peace with Germany (activities that also led him to be dismissed from his fellowship at Trinity College, though he was reinstated the following year). While in prison, Russell wrote his Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy (1919) and began work on The Analysis of Mind (1921).

In the face of Soviet and Nazi atrocities, Russell’s pacifism became more moderate. But he remained broadly anti-war and was sympathetic to many of the liberal causes of the day. He was also dismissive of religion, describing himself as both an agnostic and an atheist. In March 1927, he gave a talk on the topic “Why I am not a Christian,” which he published in essay form later that year. His political and religious views alone would probably have been sufficient to raise the ire of New York’s conservatives—but he had also written a book challenging Victorian notions of morality regarding sex and marriage: Marriage and Morals (1929). His personal sexual history was also somewhat scandalous: by 1940, Russell had been married three times and there were widespread rumors of multiple extramarital affairs along the way.

By the time Russell was appointed Professor of Philosophy by the College of the City of New York, he was among the world’s leading intellectuals. He had lectured at Oxford, Harvard, the Universities of Peking, Upsala, Copenhagen, and Barcelona, and the Sorbonne. In addition to his Cambridge fellowship, he had held positions at the London School of Economics, the University of Chicago, and the University of California at Los Angeles. He had already authored dozens of books and received awards from the Royal Society, Columbia University, the London Mathematical Society, and the Reale Accademia dei Lincei, among many others. But his pacifism, atheism, and allegedly libertine sexual views made his presence at the college offensive to some.

When Russell’s appointment was announced, the Episcopal bishop William T. Manning told the press that the philosopher was “a recognized propagandist against religion and morality … who specifically defends adultery.” Other objections to Russell soon followed. Charles Tuttle, one of Manning’s congregants and a member of the Board of Higher Education, attempted to persuade the Board to revoke the appointment. A Mrs. Jean Kay, described only as “a Brooklyn taxpayer” filed a lawsuit, asking the New York Supreme Court to vacate Russell’s appointment on the grounds that he was an alien [i.e., a foreigner] and an advocate of sexual immorality, who posed a threat to young women.