Free Speech

Tolerating Intolerance: The Free Speech Paradox

Should society tolerate intolerance to protect freedom of expression? A deep dive into Karl Popper’s ideas and modern free speech debates.

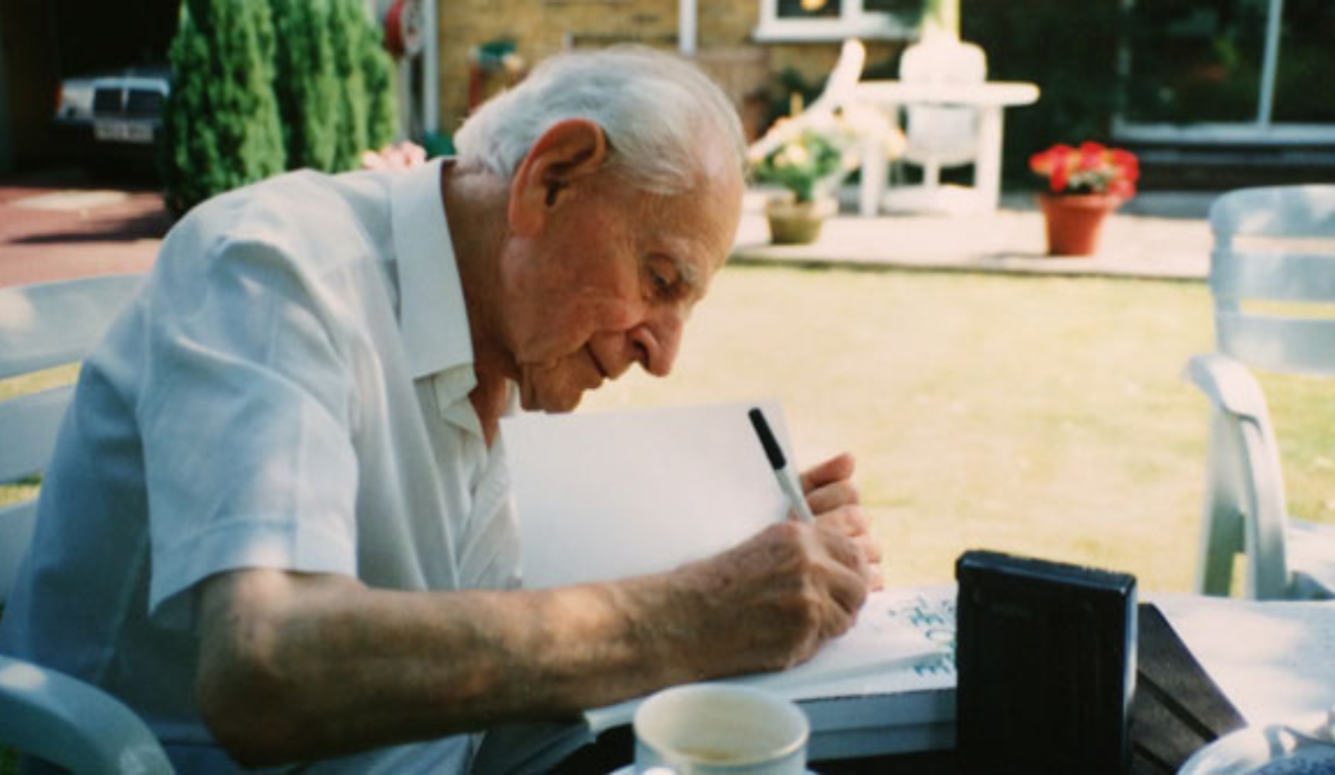

The philosopher Karl Popper may be best known for his “paradox of tolerance,” a term that comes from a footnote in his book The Open Society and Its Enemies. The paradox states that a society that tolerates intolerance can eventually succumb to it, and as a result intolerance of intolerance—even resisting it by force—may be necessary for self-preservation. The paradox is often used to justify hate speech laws and other forms of censorship, based on the rationale that there must be limits to what a tolerant society can accept if it is to survive.

Proponents of free speech sometimes face a similar paradox: we must defend speech that calls on us to suppress “unpopular” views. Some are concerned that if you protect people’s right to voice their support for censorship, you are thereby undermining free speech and sowing the seeds of its own undoing. But this apparent contradiction is illusory, because the true power of free expression is revealed even in defenses of speech advocating against it.

Take the recent dustup between Twitter/X Corp. and the Center for Countering Digital Hate (CCDH). CCDH’s explicit goal is to remove—or have Twitter remove—“hate speech” and misinformation from its social media platform. To this end, it published a report arguing that Twitter “fails to act on 99% of hate posted by Twitter Blue subscribers, suggesting that the platform is allowing them to break its rules with impunity and is even algorithmically boosting their toxic tweets.” The organization also supports government action to regulate online hate speech, even though it is a US-based organization, and such speech is protected in America by the First Amendment.

But even if it were not, the concepts of “hate speech” and “misinformation” are anathema to free speech because they are inescapably subjective. And these principles transcend a purely American context. So why defend CCDH’s right to make such arguments to begin with?

First, under US law, CCDH has a constitutionally protected right to advocate for the removal of “hate speech.” They even have the right to demand state intervention to help them, despite the fact that the US government can’t legally grant their wishes. These efforts are deeply misguided, but they’re protected, nonetheless.

Second, though CCDH’s stance is at odds with the principle of free speech, allowing CCDH to freely voice their opposition puts the group on the radar of all those who defend free expression. Knowing what people believe is critical if we want to oppose them effectively.

This idea is encapsulated in what Greg Lukianoff calls the “Pure Information Theory” of freedom of speech: it is both instructive and valuable to know who believes what—no matter how misguided or factually incorrect that belief may be. “Both for scientific reasons and for our success as a democratic republic,” Lukianoff writes, “we need to know more, not less about the ideas in our fellow humans’ heads.”

Perhaps most importantly, we should defend the CCDH’s right to call for censorship because it is crucial to be consistent in our support for free speech. As Noam Chomsky has put it, “If we don’t believe in freedom of expression for people we despise, we don’t believe in it at all.” We must hold fast to our principles even when it is most difficult to do so, and that means that we must even defend the free expression of those who are opposed to the idea of free speech itself.

But there’s another, equally powerful reason: Free speech that advocates against free speech is philosophically self-negating.

Consider burning or otherwise “desecrating” a nation’s flag. In most countries, the act has little meaning apart from the intended disrespect. But because the United States is founded on the idea of freedom, burning the Stars and Stripes carries an additional significance—one that reinforces the freedom that the flag symbolizes. Any attempt to defile a symbol of liberty that is not met with government retaliation proves how much freedom we have and how important that is.

Similarly, the moment you argue against free expression, you are undermining your own case. The ability to call for the abolition of free speech in a country like the US that protects liberty of expression is a demonstration of how essential free speech truly is. In an authoritarian state, you would not have the right to oppose a fundamental constitutional principle of this kind. This is why the idea that “I should be free to speak my mind about how free speech should be limited” makes little sense.

There is a critical difference here between speech and action. Just as words used to communicate harmful ideas do not constitute harm in and of themselves, expression in favour of limiting speech is not itself a limitation on speech. It is simply more speech.

Of course, speech can lead to action. But the distinction between them is nevertheless crucial—and we should always err on the side of more and freer speech. There are many bridges connecting New York and New Jersey, but they remain separate US states and are governed differently as a result. So it is with expression advocating for certain actions and the actions themselves. The bridges matter, but so do the divisions. Keeping the two categories of speech and action distinct is very important if we want to preserve free expression.

Popper’s paradox is almost always misused to obscure this line between speech and action. In his footnote, Popper does say that “unlimited tolerance must lead to the disappearance of tolerance,” and warns that “if we are not prepared to defend a tolerant society against the onslaught of the intolerant, then the tolerant will be destroyed.” However, he goes on to make an important clarification. “I do not imply,” he says, “that we should always suppress the utterance of intolerant philosophies; as long as we can counter them by rational argument and keep them in check by public opinion, suppression would certainly be unwise.”

What Popper is describing as beyond the pale are not intolerant words or ideas, but intolerant actions—i.e., using censorship and violence to enforce one’s ideology or to suppress dissent. In other words, he is not arguing that some ideas are so disgusting that they should be suppressed, but that we must not allow a situation in which individuals are forcibly prevented from publicly opposing such ideas.

As the writer Jason Kuznicki has argued, “To Popper, intolerance is not to be deployed when the utterance of intolerant ideas might make you uncomfortable, or when those ideas seem impolite, or when they get you really mad.” Rather, intolerance of the sort Popper describes “is only warranted when we are already facing ‘fists and pistols,’ or, presumably, worse.”

Popper’s The Open Society and Its Enemies is an unambiguous, impassioned defense of liberty, democracy, and open debate. His paradox of tolerance is not at odds with this, although it is widely not only misused, but understood precisely backwards. What should really worry us is intolerance of tolerance, and the use of force or governmental edict to cement that.

This is why defending the right to advocate for speech restrictions is good, even if we oppose the restrictions themselves. So long as the would-be censors restrict themselves to expressing their views in speech, all free speech advocates should defend their right to do so.

The moment they cross the bridge into action, so should we.