Art and Culture

Rock of Ages

The musical legacy of Robbie Robertson is a monument to the possibilities of American song.

Don’t put me in a frame upon the mantel,

Where memories turn dusty old and grey.

Don’t leave me alone in the twilight,

’Cos twilight is the loneliest time of day.

~“Twilight,” Robbie Robertson

Strangely, when I heard that Robbie Robertson—lead guitarist and chief songwriter of The Band—had died on August 9th at the age of 80, I did not turn to The Band’s music for solace. I have listened to The Band since my early teens. I have embraced them, loved them, emulated them, played their songs, and watched Martin Scorsese’s 1978 film of their final concert, The Last Waltz, religiously over the years. But it was not “Up on Cripple Creek,” “The Weight,” “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” or any of The Band’s other standards that came to my mind in the wake of Robertson’s death.

I turned instead to “Dry Your Eyes,” the standout track, produced and co-written by Robertson, on Neil Diamond’s 1976 album Beautiful Noise. It is at once an anthem and a meditation on the upheavals of the 1960s and ’70s, sounding a note that is sad but also brassy and defiant. Its lyrics are simple, uncompromising, and uplifting, and it works hard for its moments of ecstatic resolution. “From the center of the circle, to the midst of the waiting crowd,” Diamond sings, “If it ever be forgotten, sing it long and sing it loud. And come dry your eyes.”

“It taught us more about giving than we ever cared to know,” Diamond’s assertive baritone declares as Robertson’s jagged guitar fills roll on behind, “but we came to know the secret, and we never let it go.” What and whose secret? And in the song’s enigmatic conclusion, we are told, with a vision of the sturm und drang that rocked America for over a decade back then: “Right through the lightning and the thunder to the dark side of the moon. To that distant falling angel that descended much too soon. And come dry your eyes.”

It was the perfect eulogy for Jaime Royal Robertson. Rarely a singer himself, Robertson penned songs for others to sing, whether it was his bandmates Levon Helm, Rick Danko, and Richard Manuel—always sweetened by keyboardist/resident genius Garth Hudson—or those like Diamond who took his enigmatic and evocative words for themselves and were elevated by their simplicity and inscrutable splendor. All of Robertson’s work was, in its way, epic. With it, others became epic as well.

Born in 1943 in Ontario, Canada, to a Native American woman and a small-time Jewish gangster, Robertson did not discover the identity of his father until his early teens, and ended up between worlds. Sometimes, he was ensconced with his mother’s relatives at the Six Nations reservation, where he learned to play guitar. At other times, he was in the embrace of a large family of entrepreneurial and slightly shady immigrants from the old country, who encouraged his desire to enter “show business.” While Robertson was always more vocal about his Native American heritage, he would exist forever in this liminal space, declaring in “Testimony,” one of his best solo tracks, “Come bear witness, I’m wailing like the wind. Come bear witness, the half-breed rides again.”

Meanwhile, as a young member of rockabilly singer Ronnie Hawkins’s backup band The Hawks, in which he met his future bandmates, Robertson went about forging a distinctive guitar style that synthesized blues and rock into a volcanic whole. Guitar players, generally speaking, are either diggers or dancers. The dancers, like BB King and Eric Clapton, float over the instrument’s neck, rolling out elegant and elongated lines that combine power and delicacy. Diggers, on the other hand, attack the strings, ripping out notes in a cacophonic and percussive struggle with the limitations of the instrument.

Robertson was unquestionably a digger, and you can hear the electrifying collision of styles when Clapton and Robertson swap solos during “Further on up the Road” in The Last Waltz. The extraordinary results of Robertson’s playing could already be heard on early tracks like Hawkins’s cover of “Who Do You Love,” in which Robertson’s distorted and heavily reverbed guitar smash the Bo Diddley beat like a battle axe. He was still in his teens when that song was recorded.

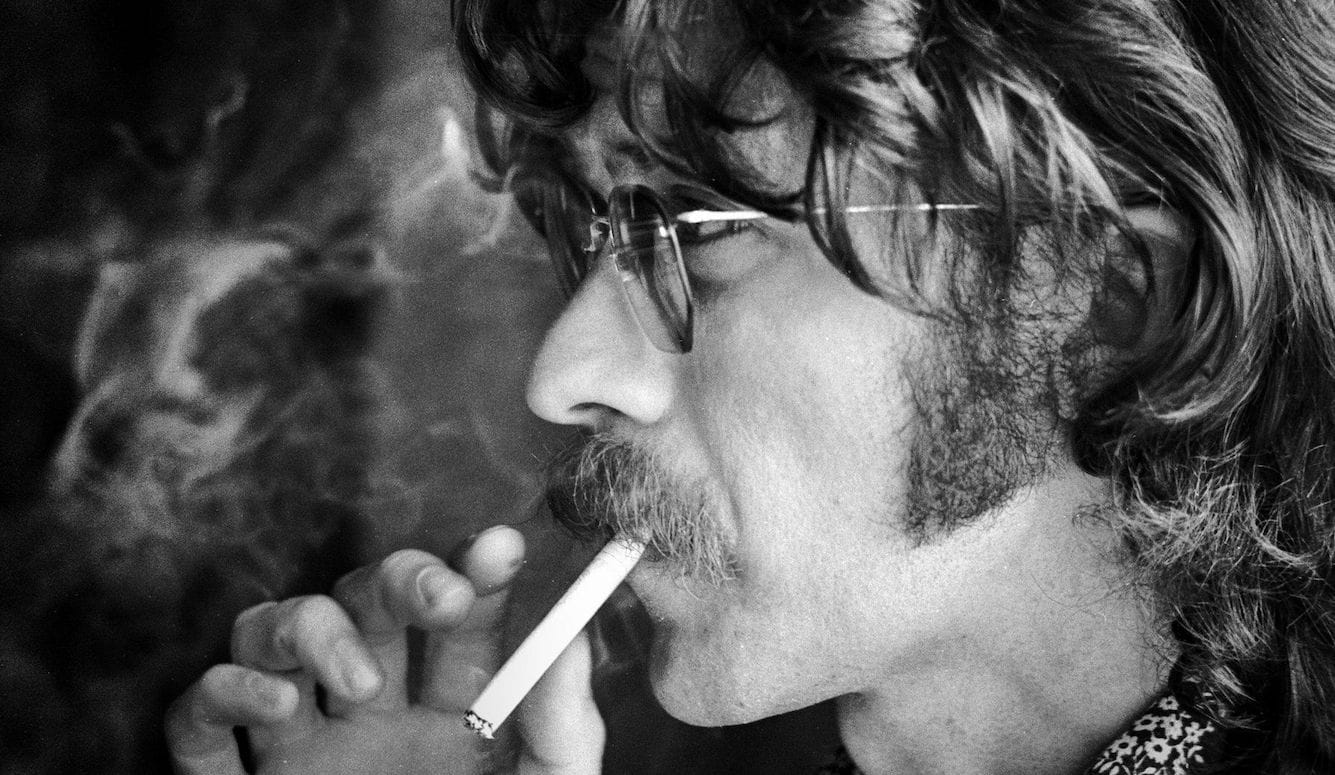

Band founder Robbie Robertson has died.

— Citizen Free Press (@CitizenFreePres) August 10, 2023

Here he is, in his day, trading licks with Clapton. pic.twitter.com/H2fLbuwfqC

As a songwriter, Robertson was a delayed child prodigy, writing one great rock n’ roll song as a teenager—the unfortunately named “Hey Baba Lou”—before setting the art form aside for a while. Robertson’s talent would erupt only after he encountered the greatest popular songwriter of the 20th century. In the mid-1960s, Robertson and what would become The Band were snapped up by Bob Dylan, who was searching for a gang of bandits to help him “go electric,” much to the consternation of his fans. Listened to today, it plainly constitutes some of the greatest rock music ever played. It towers over other practitioners of the form to such a degree that it is not even rock n’ roll at all but something quite unique, unprecedented, and unequaled.

But at the time, audiences were bemused if not openly hostile. Dylan and his band were ahead of the curve, and Robertson knew it. In a Substack essay about the struggle artists face as they try to transcend the confines of their own audience’s expectations, the British journalist Ian Leslie recounted the following story from that now-legendary tour:

Watch footage of Bob Dylan on his 1966 “electric” tour and he seems defiant and imperious as the audience heckles and jeers. I used to assume he relished the outrage. It wasn’t until recently, when I listened to Robbie Robertson, then a member of Dylan’s backing band, talk about the tour, that I realised quite how punishing it was. Robertson remembered it as a miserable time, for Dylan and for all of them. “People booed and threw stuff at us every night, everywhere we played,” he said. “We kept going, we played louder. But it was hurtful.”

Nobody else had been through this. It hadn’t happened before—to anyone. Stars entertained, fans applauded—that was the deal. It was utterly disorienting to have your own fans turn against you. Maybe they were right? At one point Robertson wondered if there was a problem with the sound, and asked a member of the crew to record one of the gigs. That night, Robertson, Dylan, and the others sat, demoralised, in a hotel room, listening to the tape of their show. Nobody said anything for a while, until Robertson spoke up. He said, “They’re wrong. They’re wrong. This is really good. The world is wrong and we’re right.”

While Dylan’s wild, banshee singing sat at the center of that exercise in distorted poetry, it would have been impossible without Robertson. In the live recordings of Dylan and the Hawks, including the famous “Royal Albert Hall Concert” at which an outraged fan shrieked “Judas!”, Robertson’s sinewy, slashing guitar lines on tracks like “One Too Many Mornings” and “Tell Me Momma” hack away at Dylan’s lyrics, punctuating the endless and endlessly complex stream of words with a sonic language of raw power, providing a perfect counterpoint and devastating assignation.

Hearing this kamikaze electric stomp, one would never have suspected what came next. In what now appears to be an act of pure self-preservation, Dylan jumped off the train just when it might have plowed him under. Following a motorcycle accident (that may not have been nearly as serious as it was portrayed at the time), Dylan retreated from a hectic touring schedule sustained by amphetamine consumption into matrimonial seclusion in upstate New York, bringing most of The Hawks with him.

Turning away from rock at the moment when he was about to be crowned its king, Dylan and his band then all but founded Americana music through informal recordings that would come to be known as The Basement Tapes, a collection of charming low-fi oddities that dug deep into the firmament of American folk, blues, and country music.

It was during this time that Robertson emerged as Dylan’s disciple in the art of songwriting. There had been imitators before, of course, but Robertson was perhaps the first to grasp the vertiginous possibilities Dylan had created without attempting to copy him. Instead, in a growing body of his own work, Robertson forged an allusive and ironic style, blessed with lyricism and a careful, haiku-like simplicity. If Dylan’s songs were concrete assertions, then Robertson’s were closer to mythology, an evocation of atmosphere. The two men, in the best sense, fed off each other. Without Robertson, Dylan would never have learned the virtues of distortion and volume. Without Dylan, Robertson would never have become a poet.

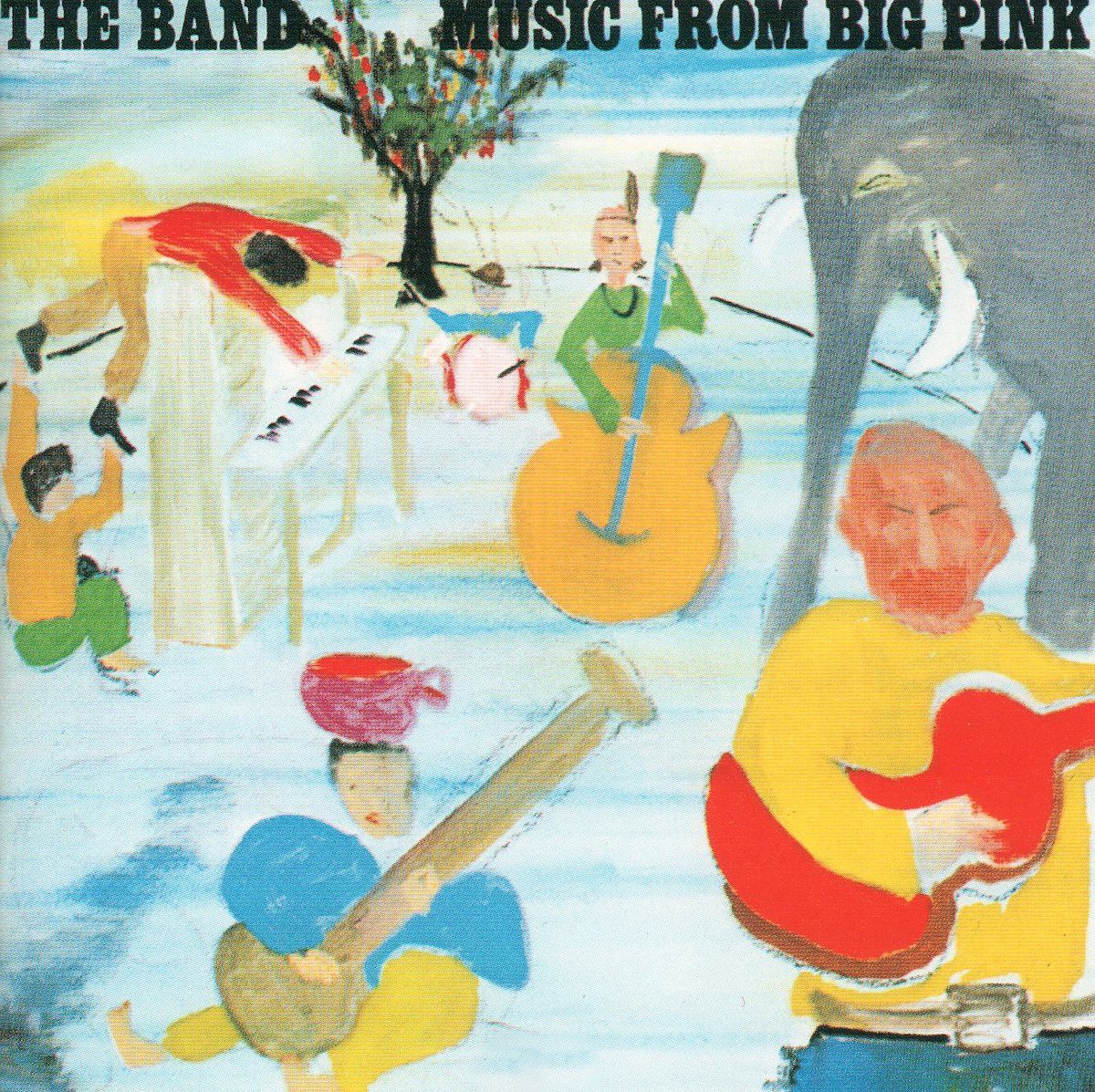

Robertson’s own genius would be revealed on The Band’s eternally seminal debut album, Music From Big Pink. The record was named for the rustic pink house in which the songs were created, and arrived in a sleeve illustrated with one of Dylan’s rudimentary paintings. It is difficult to overstate the impact that it had on the American music scene in 1968. It launched a thousand career changes, and everyone from the Beatles to the Grateful Dead to Elton John to Eric Clapton abandoned psychedelic excess in favor of the concision and clarity of songs like “The Weight,” with its echoing acoustic guitar and drums, and lyrics populated by motley characters on their way to perdition.

For the most part, Robertson surrendered vocal duties to Helm, Danko, and Manuel, whose pure gospel-inspired harmonies would help to define The Band’s sound. They provided Robertson with the canvas on which his lyrics could say little and imply everything. His songs evoked bygone worlds and obscure legends dredged from the deepest recesses of the psyche of the nation of which he was not a citizen but had come to understand as, perhaps, only a foreigner could.

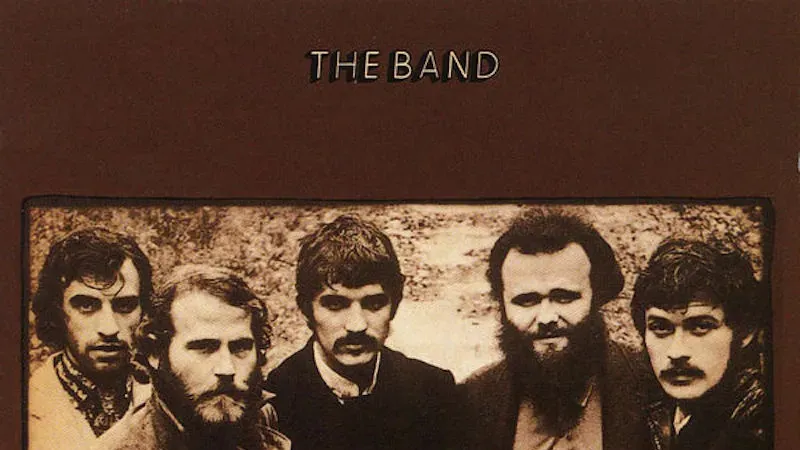

Robertson’s talent as a chronicler of America’s collective unconscious was fully realized in 1970 on The Band’s eponymous second album, their first commercially successful release. It was unvarnished proto-Americana. In “Up on Cripple Creek,” “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” “The Great Divide,” and especially the epic “King Harvest (Has Surely Come),” Robertson seemed to evoke America’s shattered soul, reeling from the upheavals of the past decade yet suspended in a state of imminent resurrection. The Band felt like a work of the 19th century, when manifest destiny was about to be realized. The nation had emerged from the horrors of Civil War into a new promethean world, though it did not shrink from the traumas and tragedies of its past.

It would be The Band’s last truly great album. Its sequel, Stage Fright, contained several moments of genius, including the title track, “The Shape I’m In,” the beautiful “The Rumor,” and the lullaby “All La Glory,” but there were also mediocrities like “Daniel and the Sacred Harp.” Cahoots was even more disappointing, with only a few glories like “Life Is a Carnival” and a marvellous cover of Dylan’s “When I Paint My Masterpiece.”

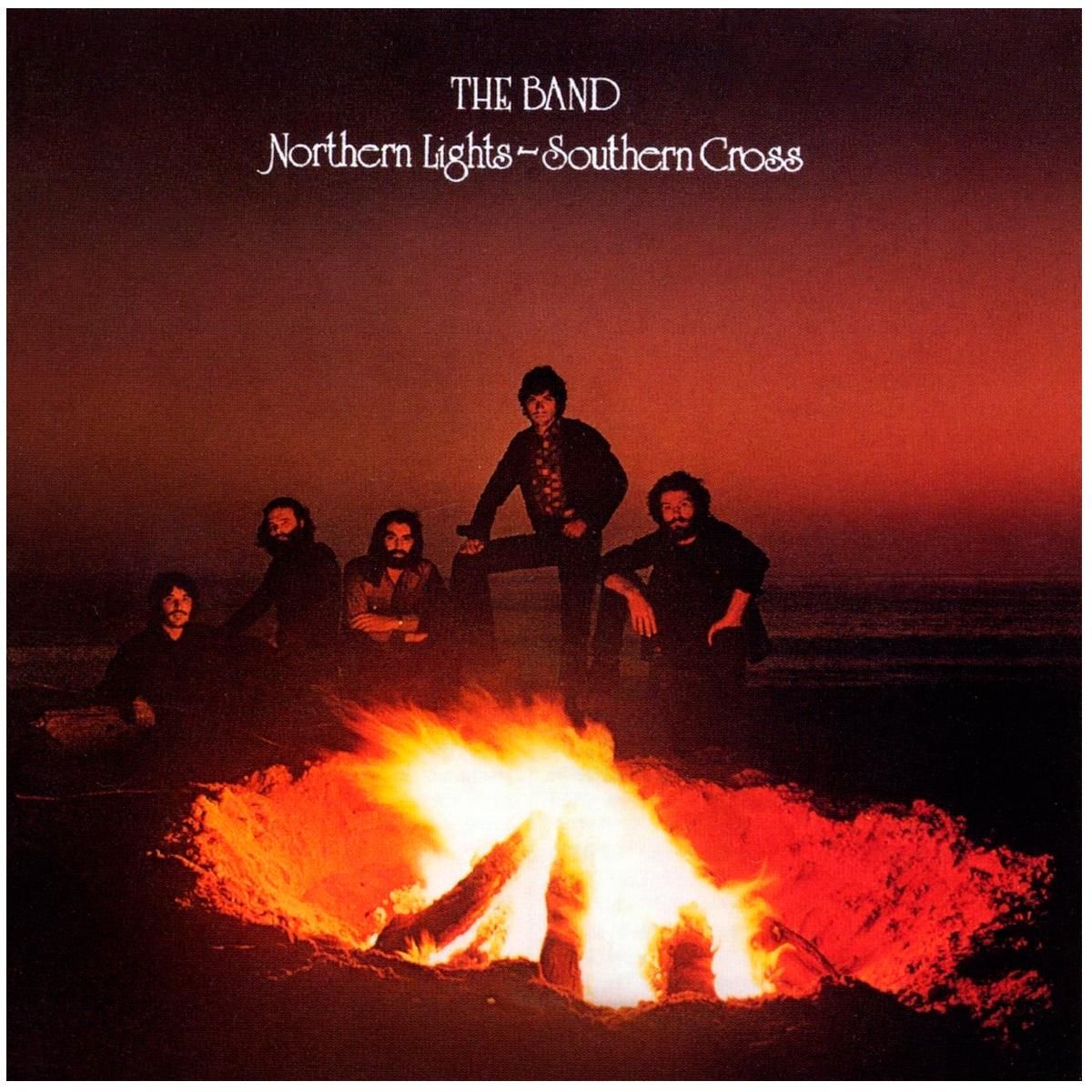

The Band’s one triumph in its latter days was the elegiac 1975 album Northern Lights-Southern Cross, with its storming opener “Forbidden Fruit,” the beautifully sung ballads “Hobo Jungle” and “It Makes No Difference,” the epic tribute to Canadian history “Acadian Driftwood,” and the wailing old-timey “Ophelia,” which included glorious lines like: “Ashes of laughter, the ghost is clear. Why do the best things always disappear? Like Ophelia. Please darken my door.”

There was also the extraordinary live album Rock of Ages, featuring some of Robertson’s finest Telecaster playing and a blistering cover of Marvin Gaye’s “Don’t Do It.” That track would later be the last song The Band ever played together, at the end of their final concert, appropriately titled The Last Waltz. The show would be one of the great events of rock n’ roll and something like the beginning of its epitaph. Indeed, when it was held in 1976, disco was already looming as the first intimation of the computerized, auto-tuned wasteland that American pop music would eventually become.

The decision to bring The Band to a close was that of an intelligent man. Robertson had the self-possession and self-awareness to understand that the road was threatening them all. Several of his bandmates had sunk into alcoholism and heroin addiction, and the endless highway was wearing them down at a precipitous and disturbing pace. ”It's a goddamn impossible way of life,” Robertson told Scorsese. It had to end, he later remarked, “or someone’s gonna die.”

The Last Waltz featured The Band in one final soaring triumph along with a multitude of guest stars, including Joni Mitchell, Muddy Waters, Van Morrison, Neil Young, and their old mentor Ronnie Hawkins himself. Finally, The Band’s onetime fearless leader Dylan appeared to sing his hymn to freedom “I Shall Be Released” with Richard Manuel. The event wrote itself into rock history and resulted in what is perhaps the greatest concert film ever made, and certainly one of the finest music documentaries. When I saw the film on the big screen some years ago, the audience sang along and applauded each song. We were all there again on that stage in what Bernardo Bertolucci called “the amniotic darkness” of immortal cinema.

Sadly, Robertson’s prediction that “someone’s gonna die” turned out to be prescient. He never returned to the road, but The Band reformed without him under the leadership of drummer and vocalist Levon Helm. Lacking their best songwriter, however, they floundered, and the road took its pound of flesh. Manuel, beset by depression and alcohol, killed himself in 1986. Rick Danko died tragically young at 55 in 1999. Helm himself fell to cancer in 2012. Worst of all, perhaps, after The Last Waltz, none of them wrote another decent song.

Robertson did write a few in the years to come, sporadically releasing solo albums that contained the occasional gem like “Broken Arrow” and, especially, the howling “Testimony.” But mostly, he dedicated himself to supervising the soundtracks to Scorsese’s films and stayed out of the spotlight. What remains of Robertson is not so much the great and legendary songs, but brief stolen moments—his own ashes of laughter. The obscure Basement Tapes track “Bessie Smith,” for instance, co-written and sung with Rick Danko—a quiet psalm to American music with a chord progression that echoes Smith’s own masterpieces and piercingly simple lyrics: “I’m just goin’ down the road to see Bessie Smith, when I get there I wonder what she’ll do” and “Now and again I still wonder to myself, was it her sweet love or the way that she could sing?”

One senses that Robertson was a model of the work ethic, of what labor could give you, famously bent over a piano or a mixing board while his compatriots were off tending to their vices. The mercurial Dylan claimed to have written “Blowin’ in the Wind” in 15 minutes—which is likely true—but one cannot imagine his protégé doing the same. Robertson’s work is deceptively complex, elegantly structured, framed and photographed like the movies he loved. It would have required time and sweat to realize.

But however much he worked over his songs, there was unquestionably poetry in him. It is there in his words and his playing, reaching for a touching moment, indelible in the mind of the listener. His moment of true creative vitality was relatively brief, but he managed to keep a fractious band of brothers together through the worst of times, and if they had taken his advice and abandoned life on the road, they might be alive today. In the end, he lost all but one of them, some of whom perished under the most tragic of circumstances.

This may be, in some terrible way, fitting, because Robertson’s words and music always had a sense of tragedy; the tragedy of the passage of time, which is the greatest tragedy of all. His best songs are lamentations, odes to other times, other places, and other people. J. Royal Robertson, the half-breed who rode into Nazareth, the sideman extraordinaire and leader of one of the greatest bands of an era that has itself passed into history, has now moved on; his ghost is now clear. His labors will stand, however, as a monument to the possibilities of American song, a quiet testimony to a tradition that can never be fully crushed beneath the weight of empty pop tarts and the musings of machines. Even ashes of laughter, we should remember, are joyous things. If it should ever be forgotten, sing it long and sing it loud. Dry your eyes.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated the date of Richard Manuel’s death. Apologies for the error.