Canada

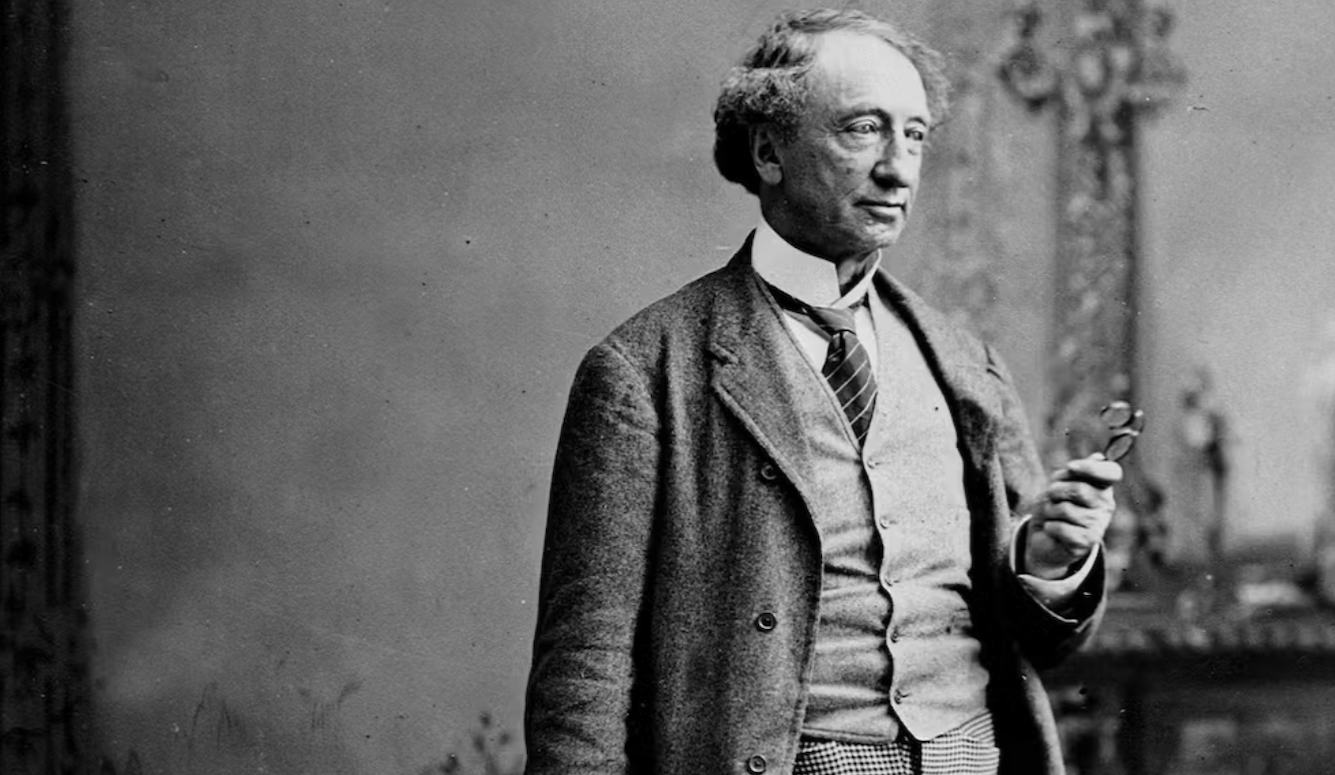

Celebrating the Legacy of Canada’s First Prime Minister

Far from being an ‘architect of genocide,’ John A. Macdonald championed policies that were humane by 19th-century standards

Given that Sir John A. Macdonald died in 1891, the facts of his life are obviously unchangeable. The story of his life, however, has changed dramatically in recent years.

During his life, and for well over a century after his death, Macdonald was regarded as Canada’s foremost founding father and one of the country’s most colourful characters. Confederation was very much Macdonald’s singular achievement—the product of his masterful skill at negotiation, plus plenty of patience and resolve. His contemporaries also praised his sunny disposition and lively sense of humour.

While Macdonald’s fondness for the bottle and involvement in a serious political scandal would eventually temper history’s judgement, he was nevertheless considered a nation-builder worthy of celebration and veneration. Today, on the other hand, he is routinely cast as a war criminal—the “architect of genocide against Indigenous People” as one teachers union put it. Since 2020, statues of Macdonald have been pulled down in numerous Canadian cities, including Hamilton, Montreal, Victoria, Charlottetown, and Toronto.

Yet a proper and balanced consideration of Macdonald’s life reveals that Canada’s first prime minister was directly and deliberately responsible for saving the lives of untold numbers of indigenous people. It is easily argued, in fact, that no Canadian politician before or since has had such a salutary impact on the fate of Canada’s native population. Given the temper of our times, this is not likely to be a popular notion. But that does not make it any less true.

Avoiding War and Abiding by TreatiesCanada’s treatment of its indigenous people under Macdonald is best understood in comparison with that of the native population in the United States. Given the geographically arbitrary location of the Canada-US border, we can consider the divergent experiences on either side of it to constitute a natural (albeit, for some, decidedly tragic) experiment. The results very much favour Macdonald’s Canada.

By and large, American settlers entered indigenous lands ahead of any formal government presence, and without negotiation with the original inhabitants. What treaties were signed between native tribes and the government were often abrogated as soon as it was in the interests of white settlers to do so.

This process—what might be considered a “settlement first, negotiation second” approach—inevitably led to conflict and war. In 1890, as part of its regular census of the native population, the US Congress requested a calculation of all lives lost in the more than 40 individual wars that had been fought between indigenous tribes and American settlers or government troops since the signing of the US Constitution in 1789. The government’s best estimate for this hundred-year period put the death toll at 45,000 natives and 20,000 white soldiers and settlers. A more recent academic study using more advanced statistical methods raises the native death toll to 60,000.

Looking only at conflicts in the American West between 1850 and 1890—the period most relevant to the settling of Canada’s Prairies—the Encyclopedia of Indian Wars indicates that 6,600 whites and 15,000 natives were killed or wounded in battles during this four-decade span. (It should be noted that these figures do not include the loss of life caused by government policies carried out at gunpoint outside of war. The Trail of Tears, for example, is estimated to have caused 4,000 to 8,000 native deaths, an astounding casualty rate of 25–50 percent.)

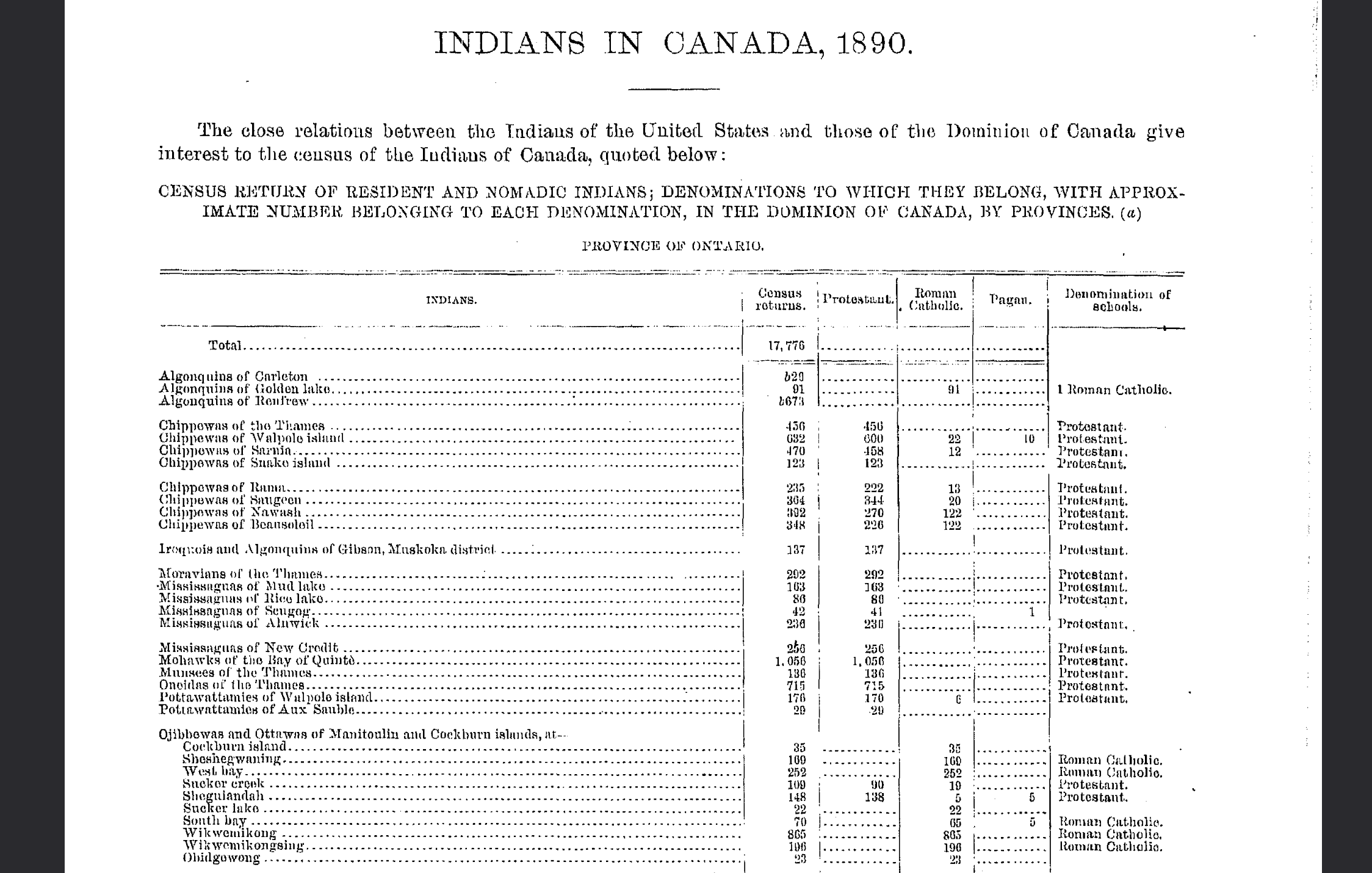

Standing in stark and—from the Canadian perspective—greatly uplifting contrast to these appalling figures is a companion document to the 1890 US Congress report, concerning the Canadian experience. Significantly, it makes no mention of any death toll arising from “Indian Wars” in this country. This was not an oversight. Since the British conquest of New France in 1761, there were no significant wars in what is now Canada prior to the Riel Rebellion of 1885. And this solitary armed conflict was a Métis uprising notable for its lack of large-scale native participation; the First Nation death toll from the entire conflagration was no more than a few dozen.

Such a long and, it must be said, happy period of peaceful relations between indigenous and white populations in Canada was largely the result of British policy that sought to make and keep treaties with native communities. Recall that one of the American Revolution’s underlying causes was the British colonial government’s determination to prevent white settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains, a commitment made in the Royal Proclamation of 1763. The British approach is best characterized as “negotiation first, settlement second.”

As Canada’s first prime minister, Macdonald was extremely proud of this legacy of peaceful co-operation and co-habitation. And he was determined to maintain such a policy while overseeing the settlement of Canada’s West.

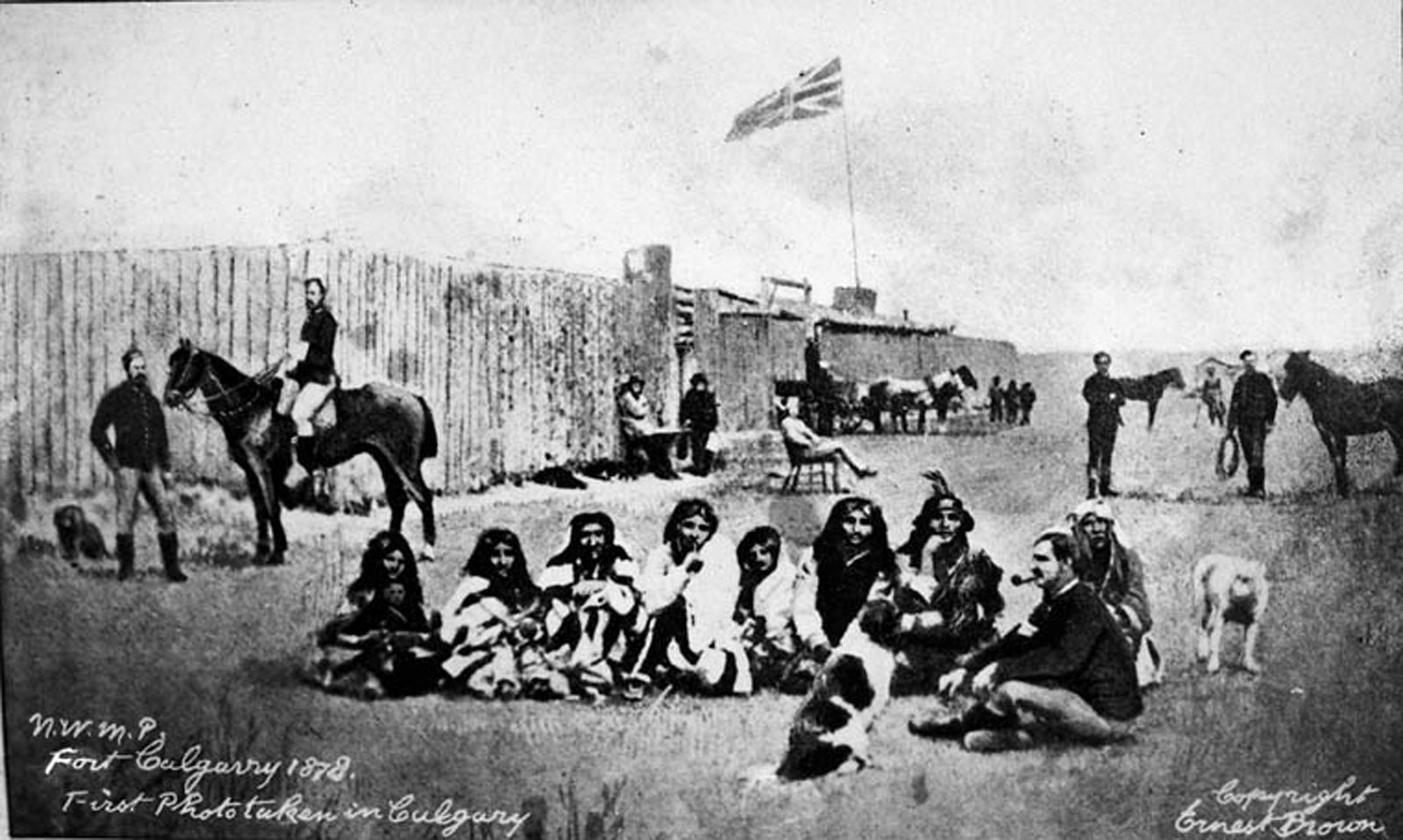

The creation of the North-West Mounted PoliceAnother key piece of Macdonald’s plan to avoid white/native conflict in Canada’s new western territory was to create a police force that would establish a system of law and order on the Prairies ahead of white settlement—again, in contrast to the American experience.

The North-West Mounted Police (NWMP), the precursor to today’s Royal Canadian Mounted Police, was meant to deter incursions from the United States and protect the legal rights of both natives and settlers once settlement began. Notwithstanding claims that the modern-day RCMP is riven with racism and sexism, the force’s very existence stands as testimony to the Canadian government’s intention to protect the native population from depredation and genocide.

The design of the NWMP was deeply influenced by a report from Lt. William Francis Butler, a British soldier who toured the Canadian west at Macdonald’s request in 1871. Butler had previous travelled the American Plains and was outraged by the “terrible, heart-sickening deeds of cruelty and rapacious infamy” arising from the American “wars of extinction” waged against indigenous people. He was determined that Canada should avoid such a disaster, and proposed the creation of a mounted police force and system of travelling magistrates to protect the indigenous population and bring a formal process for justice to the Prairies. Macdonald wholly embraced this vision.

Settlement of the Canadian west began in earnest in the early 1880s, and led, as expected, to increased instances of conflict between settlers and natives on and off reserve lands. Considering the accusations made against Macdonald today, it is noteworthy that he was criticized in his time for instructing the NWMP not to show favouritism toward white settlers. Rather, he argued, it was their proper role to protect the rights of native and settler alike.

Macdonald wished to install a functioning justice system in the Canadian west prior to white settlement, to protect native interests. His enlightened view on this score will no doubt come as a surprise to his many present-day detractors. But again, it is part of the true historical record. Through such policies, Macdonald undoubtedly saved many native lives from American-style frontier “justice.”

Smallpox VaccinationThe arrival of smallpox to North America was disastrous for native populations across the continent, since they had no natural resistance to this deadly disease. In the 1830s, for example, an epidemic originating in the American west migrated north and killed three quarters of all Natives living in the Edmonton area.

Prior to Confederation, the governments of Upper and Lower Canada, under the joint leadership of Macdonald and George-Étienne Cartier, had organized a vaccination campaign for provincial native populations as part of a comprehensive public health program. This was highly effective, and the effects were quickly felt.

Once Canada took over the Hudson’s Bay Company lands, smallpox vaccination was gradually expanded to include all native Canadians in the western territories as well. During the Liberal administration of Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie, Dr. Daniel Hagarty was appointed medical superintendent for the Canadian west and given the huge responsibility of vaccinating the entire indigenous population. This objective was maintained following Macdonald’s return to power in 1878. And it was tremendously successful. In some native communities, the vaccination rate hit 100 percent, a remarkable feat that is rarely duplicated today.

This nation-wide policy was so successful that in 1885, when a particularly deadly smallpox outbreak killed 3,000 residents of Montreal, the Kahnewake native reserve across the river reported “but very few cases” of the disease. Everyone on the reserve had already been vaccinated by the federal government.

Untold numbers of indigenous people died throughout the Canadian west prior to the 1870s as a result of smallpox. Yet due to the commitment of Liberal and Conservative administrations, the death toll among native Canadians from the disease by the 1880s and beyond was close to zero. Macdonald deserves his share of the credit for this fact.

Famine Relief for Natives on the PrairiesThe gravest charges against Macdonald’s legacy involve his role in the famine among the indigenous population of the Prairies following the collapse of North America’s buffalo herds in the late 1870s. The claim that Macdonald was responsible for a “state-sponsored attack on Indigenous communities” by denying food relief in order to open the Prairies to white settlement is forcefully made in the 2014 book Clearing the Plains, by University of Saskatchewan historian and notable Macdonald critic James Daschuk.

Perhaps the most stinging indictment comes from Macdonald’s own words. Daschuk twice quotes Macdonald saying, in 1882, that his government was “doing all we can, by refusing food until the Indians are on the verge of starvation, to reduce the expense.” This line is also repeated in many current-day condemnations of Macdonald as evidence of his lack of compassion for indigenous people.

The near-extinction of the continental buffalo herds caused tremendous hardship for Canada’s western indigenous communities, which depended on the meat, bones, and hide of the buffalo for much of their sustenance and supplies. While this outcome was widely predicted in the late 19th century, it occurred much faster than anyone expected.

When the famine arrived with unexpected swiftness in 1878, the government reacted as its treaties dictated. Macdonald told the House of Commons that the “absolute failure of the usual food supply of the Indians in the North-West” created the “necessity of a large expenditure in order to save them from absolute starvation.” A year later, Macdonald announced a special council to investigate the food crisis and to “supply food to the Indians.” Natives living on reserves were provided aid, mostly flour and bacon, as per the government’s obligations. Tribes not living on their reserve land, however, had their relief provisions withheld or reduced in order to induce them to move onto reserves as a negotiation tactic. Macdonald describes his policy in more detail in 1886 House of Commons debates:

To the Indians who go upon their reserves we give food until they are able to support themselves, but we reduce them to half rations when they are simply wandering and demoralised Indians … When these people are hanging about the Government stores and offices, we reduce them to as low a ration as is sufficient to keep life in their bodies; but we tell them: ‘Go to your stations and we will give you food to take you there, and you will get full rations until you are able to support yourselves.’

In making this statement, Macdonald was responding to the charge of excessive generosity, which had been made by members of the Liberal opposition. And while “half rations” may sound draconian to modern ears, and was no doubt uncomfortable, it was not a death sentence.

Keep in mind that no treaty obligated the federal government to provide any rations to natives living off-reserve. Even Daschuk acknowledges that “Rations kept many from starving.” The reduction for some was meant to encourage natives to return to their reserves, where the treaties they signed required them to be. Recall that it was this strict and legalistic approach to treaties that distinguished Canada’s native experience from the bloody and arbitrary American approach.

Macdonald allocated considerable government resources to fulfilling its famine-relief duties. In 1878, the federal budget for Indian Affairs was a rather modest $276,000. By the peak of the famine in 1884, this item had grown to $1.1 million, outweighing National Defence by a substantial margin.

Residential SchoolsResidential schools also figure prominently in popular claims that Macdonald was responsible for a “genocide” of indigenous people. In fact, the first such schools appeared in Canada in 1695, long before Macdonald’s tenure. And their application to western Canada cannot properly be regarded as a government plot to permanently eliminate native culture. Under the seven numbered treaties, the federal government was obligated to build and staff such schools only when requested to do so by native leaders, or, as Treaty Six clearly states, “whenever the Indians of the reserve shall desire it.”

And they clearly did desire it. During Macdonald’s tenure as prime minister, no fewer than 185 on-reserve day schools and 20 residential schools were built. This reveals a strong interest among native leaders to have their children given a western-style education, as well as a preference for local over residential schools at this time.

And attendance was entirely voluntary. Although the Progressive movement across North America at this time was pushing governments everywhere to make schooling universally compulsory, Macdonald resisted this for native children. Without parental support, he believed, native education would not succeed. Accordingly, it was left up to native parents to decide whether their offspring should go to school. This policy continued long after Macdonald’s death. As late as 1920, attendance at all native schools in Canada was still entirely voluntary.

Macdonald’s legacy is complicated by the passage of time and changing perspectives. But through careful study of his own words and deeds, as well as the reports and actions of his officials, contemporaries, native chiefs, and political opponents, what emerges is a clear and powerful picture of his enlightened view towards indigenous people and his strong sense of moral purpose. If Macdonald’s story has changed, it’s because Canadian society no longer understands its own history.

Greg Piasetzki is a Toronto lawyer and a member of the Métis Nation of Ontario. This text, portions of which appeared in C2C Journal, is adapted from the Aristotle Foundation’s newly published book, The 1867 Project: Why Canada Should be Cherished—Not Cancelled, which contains the work of 20 authors, including editor Mark Milke.