Chaucer

Chaucer’s Bawdy Broad

More than six centuries after The Canterbury Tales first appeared, the Wife of Bath still has lessons to teach about love, sex, marriage, and—yes—feminism

The Wife of Bath is everyone’s favorite character in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. Raunchy, boisterous, wine-tippling, and determined to have her way in relationships with men, the 40-ish, five times-married (starting at age 12) Wife is the most vividly realized of the thirty-odd pilgrims from various walks of life, including Chaucer himself, who people the poem with their personalities and storytelling as they ride from London to Canterbury Cathedral and the shrine of the “hooly blisful martir” St. Thomas Becket.

In a rambling Prologue to her Tale, the Wife, describing her sexual adventures as a youthful bride with her first three rich but elderly husbands, declares, “I laughe whan I thynke / How pitously a-nyght I made hem [them] swynke.” It is hard not to admire her forthrightly expressed appetites and her entrepreneurial energy in using her “quoniam” (it means what you think it means) to perhaps hasten the deaths that left her a wealthy and respectable widow with the time and means to travel at her leisure to sacred sites.

As for her late fifth husband, 20 years her junior and an Oxford dropout named Jankyn, their marriage, as she describes it, consisted of her successful battle for the “maistrie [mastery],” as she pried him away from his “book of wikked wyves,” a compendium of classical and biblical stories about women making their husbands’ lives miserable: Eve, Delilah, Clytemnestra, Socrates’ Xanthippe who “caste piss upon his head.” The Wife boasts: “I ... made hym brenne [burn] his book anon right tho.”

Chaucer himself was clearly mesmerized by the Wife of Bath. He gave many of his pilgrims’ tales short prologues in which the pilgrims talk about themselves or argue with other pilgrims (the Wife does much of both). But the Prologue that Chaucer wrote for the Wife dwarfs all the rest in length at 858 lines (the second-longest is the Canon’s Yeoman’s Prologue at a mere 166 lines plus some confessional material in his Tale itself).

Furthermore, two other pilgrims, the Clerk and the Merchant, make references to the Wife and her thoughts about marriage in their own tales. And Chaucer himself, in a later poem addressed to a mysterious figure he called “Bukton,” humorously advises his friend to “rede” the “Wyf of Bathe” and thus avoid the “trappe” of wedlock. As Marion Turner, an Oxford professor and well-regarded Chaucer biographer, writes in this latest book, The Wife of Bath: a Biography, “This was only the beginning of [the Wife’s] long career as a bookrunner—a figure that escapes her own text.”

Fittingly for Turner’s purposes, The Wife of Bath: a Biography is as much a narrative of the Wife’s centuries-long afterlife in the writings of others as it is a study of her appearance in the Canterbury Tales. Turner leads the reader through these literary reincarnations of “Alison” (Turner’s modernization of the praenomina “Alisoun” and “Alys” that the Wife uses at two separate points in reference to herself—although she is always “the Wyf [or “Wif”] of Bath” to Chaucer and the other pilgrims, just as the Knight is always “the Knyght”).

The scribes who copied down the earliest manuscripts of the Wife’s Tale, which started appearing shortly after Chaucer’s death in 1400 (these are the days before the printing press), often added their own running commentary in the margins, some of it extensive and disapproving. Turner, whose interpretation of the Wife and her Tale is ardently feminist, accuses those glossers of trying to “silence” the Wife; “misogyny” and “patriarchal” are oft-reappearing word in Turner’s book. Indeed, the Wife, touting her own “experience” as a counterweight to the “auctoritee [claimed authority]” of the written portrayals of women that educated men have produced, has lately become a feminist role model.

As the decades after Chaucer’s death rolled on, the bawdy-tongued Wife became the stuff of sometimes-censored Elizabethan and Jacobean ballads (“The Wanton Wife of Bath”), and Turner maintains that she was also the inspiration for Falstaff, Shakespeare’s hearty dipsomaniac who dresses in women’s clothes in the Bard’s Merry Wives of Windsor.

By the late 17th century, as standards of elevated taste became more decorous, the poet John Dryden, who admired Chaucer and sought to introduce him to a wider audience, turned some of the Canterbury Tales into then-modern English heroic couplets so that his contemporaries who might find Chaucer’s medieval diction daunting could read them easily. Dryden balked, however, at translating the Wife’s Prologue, which he deemed too “licentious” for the 17th century.

A generation or so later, Alexander Pope, another Chaucer enthusiast and modernizer, did tackle the Prologue, but felt compelled to bowdlerize it. Pope omitted, for example, the Wife’s declaration that she has the mark of Mars [“Martes mark”] in a “privee place,” her admission to sexual ravenousness (“bothe eve and morwe [morning]”), and her desire, as Chaucer had her express, to make each of her husbands, including a hoped-for future sixth, her “thral” both inside and outside the marriage bed. The cleaning-up efforts of Dryden and Pope foreshadowed 19th-century projects to make the Wife and her Tale even more genteel, especially when it came to the Victorian pedagogical penchant for rewriting literary classics—Chaucer, Shakespeare’s plays, Ovid’s Metamorphoses—as moralizing children’s stories.

This sanitizing tide turned only in the 20th century, when it turned hard in the opposite direction. Turner argues persuasively that James Joyce, an avid amateur medievalist, used the Wife of Bath as a model for the loquacious and promiscuous Molly Bloom—although it must be said that Chaucer’s creation, earthy diction notwithstanding, is actually a churchgoing “worthy womman” and a model of spousal fidelity (no Blazes Boylan for her). Nor did Chaucer share Joyce’s Leopold Bloom-ish fetish for unpleasant bodily fluids and smells in connection with sex.

Moving forward in time somewhat selectively, Turner dissects Pier Paolo Pasolini’s oversexed 1972 film version of The Canterbury Tales, in which the Wife literally kills her fourth husband via genital overexertion and gives Jankyn, her youthful fifth husband, a hand-job before proposing marriage to him (a scene most definitely not in Chaucer), to which Jankyn, who seems not to find older women appealing, responds … flaccidly. Turner bemoans this sort of rewriting: “[O]ver and over again, we see Chaucer’s successors re-inscribing the story with patriarchal, misogynist myths about the horror of female sexuality.”

The Wife fares more positively, in Turner’s view, when women take her over, as in the poems and plays of several 21st century postcolonial black female poets and playwrights. One is Zadie Smith, whose The Wife of Willesden, which premiered in London in 2021, closely follows Chaucer (including his iambic pentameter verse form) but in contemporary Jamaican patois: “I been / Married five damn times since I was nineteen!” (Curiously, Turner passes over Peter Ackroyd’s dark 2003 take on Chaucer, The Clerkenwell Tales, in which the Wife of Bath is a procuress who sells impoverished young girls to be deflowered by wealthy middle-aged men.)

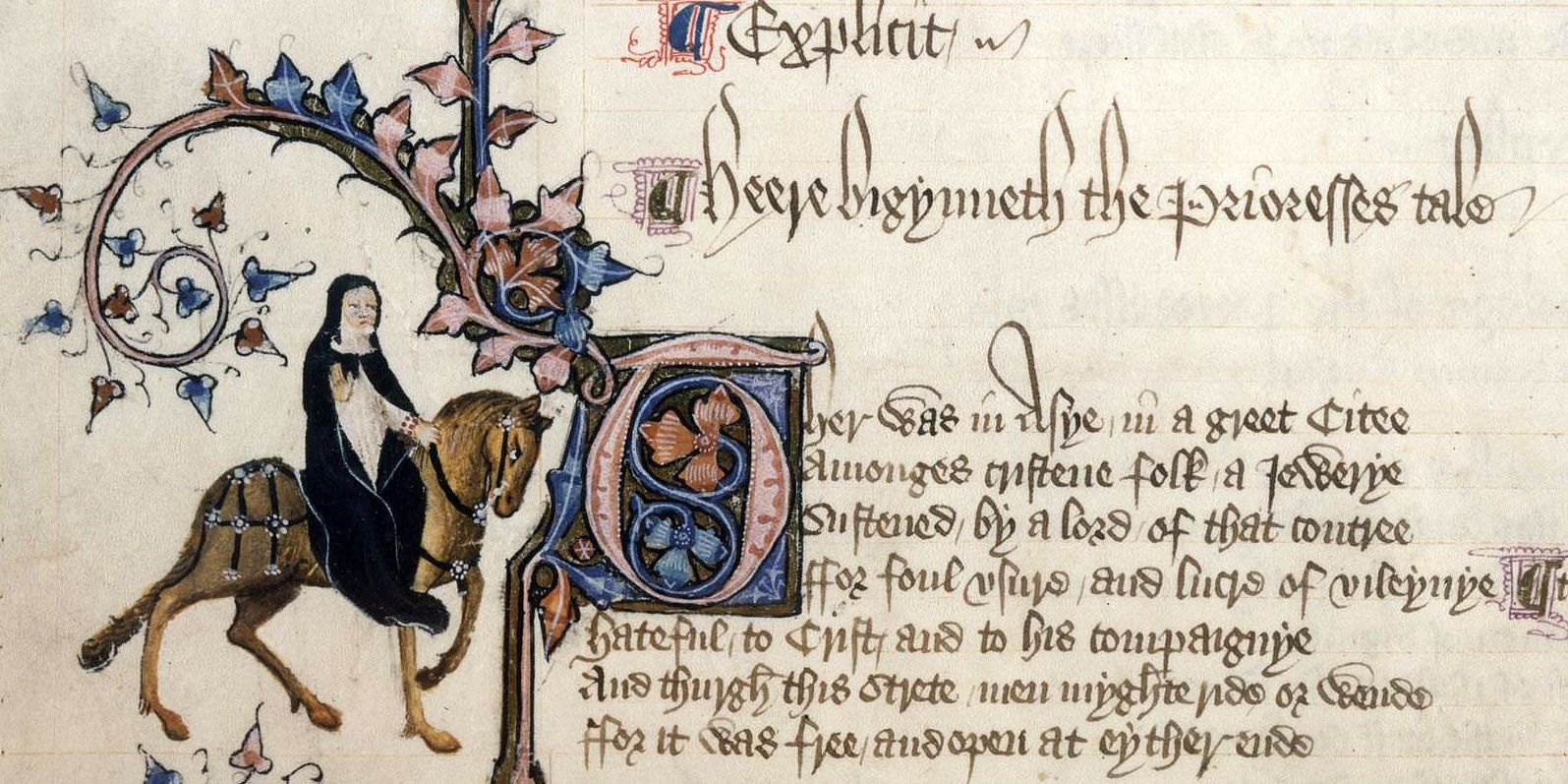

One of the first people to read the Canterbury Tales and be entranced enough by the Wife of Bath to offer a distinctive perspective was actually not a writer at all. He (or possibly she) was one of the artists who painted miniatures of 23 of the Canterbury pilgrims in the margins of the Ellesmere Manuscript, a deluxe complete edition of the Tales produced during the first decade after Chaucer’s death and possibly inked by the same scribe whom Chaucer had employed to turn out copies of his works during his lifetime. (The Ellesmere miniaturist’s portrait of the Wife of Bath figures in the jacket design for Turner’s book.)

The Ellesmere artists depicted all the pilgrims on horseback, although the horses themselves are drastically smaller than scale so as to emphasize the dress, social standing, and personalities of their riders. They mostly relied on Chaucer’s colorful third-person descriptions in the General Prologue, a preamble that introduces the tellers to the Tales’ readers. In general, they were attentive readers of Chaucer as well as close observers of their fellow medievals. The horses, for example, are astonishingly realistic-looking, and they conform faithfully to Chaucer’s mentions of the various equine types that the individual pilgrims rode (medieval people seemed to know horse breeds as well as moderns know makes of cars).

The Wife of Bath, who is a seasoned pilgrimage traveler, rides an “amblere,” a pacing horse with a comfortable swaying gait because both its legs on one side move at the same time, in contrast to most horses’ rougher diagonal leg-movement. And so the Ellesmere artist who did the Wife’s illustration carefully painted her horse with its two right legs off the ground (“esily she sat,” Chaucer writes). To this day, horsey people sometimes use the Wife’s Ellesmere image to illustrate how an ambler moves.

In the Wife’s case, the Ellesmere illustrator supplemented Chaucer’s description of her with material from her first-person account of herself in her own Prologue. Chaucer relates that the Wife, addicted to conspicuous consumption, liked to pile 10 pounds of expensive kerchiefs onto her head every Sunday when she went to church—so the illustrator duly created a massive puffy headdress for her, topped by a hat “[a]s brood as is a bokeler or a targe [shield],” as Chaucer describes it. He also followed Chaucer’s description of the Wife as wearing a “foot-mantel,” a sleeping bag-like piece of outerwear that shielded a rider’s clothing and lower limbs from the grit and mud of medieval roads.

In a nod to the Wife’s penchant in her Prologue for letting everyone know how well-off she is, he clothes her in a costly-looking fur-trimmed red gown whose voluminous skirts (she has “hipes large,” Chaucer informs us) she has tucked into her foot-mantle. (In Chaucer’s poem, she also sports red stockings to match the scarlet dresses she favors, but we can’t see them in the illustration.)

The illustrator also added some details to his image of the Wife that are not explicitly spelled out in his source. For one thing, he has her riding astride her horse like a man, with one of the “spores [spurs] sharpe” that Chaucer gives her in prominent display on her foot-mantle-shielded left ankle. There are only three females among Chaucer’s Canterbury pilgrims. The other two are the ladylike Prioress and her companion Second Nun; both religious women ride sidesaddle in their Ellesmere illustrations with their feet hidden modestly under their habits. Not so the Wife, who declares that, thanks to alignments in her horoscope, she has both male and female traits: “Mars yaf [gave] me my sturdy hardynesse” and “Venus me yaf my lust.”

Furthermore, the artist painted the Wife with a horsewhip in her upraised right hand—another detail nowhere to be found explicitly in Chaucer’s text. I am not the first to notice that the whip in hand gives the Wife a distinct pictorial resemblance to the (fictional, as far as we know) mistress of Aristotle, a female figure who appears repeatedly in medieval and early modern literature and art.

Starting in the 12th century, as Aristotle rose to prominence as the leading ancient philosopher for Western Europeans, the story began to circulate that he had become captivated by a concubine of either his tutee Alexander the Great or Alexander’s father, Philip of Macedon. So powerful was the erotic spell she cast on the otherwise rigorously rational Aristotle that he let her ride on his back with a bridle while he crawled about on all fours. Some medieval writers gave her the name Phyllis, although François Villon called her Archipiada, perhaps in a nod to the lascivious politician Alcibiades, whose good looks were said to have attracted the homosexual interest of Aristotle, as well as Socrates and Plato.

Phyllis/Archipiada the dominatrix was a cautionary figure, personifying the power of carnal eros, associated with women, to subjugate and subject to ridicule even the greatest male intellects. In the medieval visual arts, she is almost always depicted brandishing a whip as she rides the philosopher’s back. She was almost certainly familiar to Chaucer. In 1386, the year before Chaucer started working on the Canterbury Tales, his fellow London poet and friend John Gower produced a lengthy English poem, Confessio Amantis (“the lover’s confession”), in which “the queene of Grece” bridles Aristotle (“he foryat his logique”). In homage to the Wife of Bath’s similar charms (“Boold was hir face, and fair, and reed of hewe”), the Ellesmere artist painted her as rosy-cheeked and displaying an hourglass figure that made her look quite alluring for a forty-something widow swathed in yards of headdress.

The multivalent persona that the Ellesmere miniaturist depicted provides a clue that the Wife of Bath, as Chaucer envisioned her, might have been a more complex and ambiguous type than a simple challenger to male sovereignty. For one thing, Chaucer gives her too many occupations to be truly realistic. She relates that she started her career as a professional wife when she “twelve yeer was of age.” Age 12, a threshold deriving from Roman law, was the bare minimum age at which the Catholic Church then (as well as today, at least technically) permitted females to enter valid marriages.

Archival records show, however, that with the exception of aristocratic arranged marriages, most English girls in Chaucer’s time actually wed at relatively delayed ages, anywhere from their late teens to early 20s. So the Wife is already a stylized, purely literary creation—and Chaucer reinforces her artificial nature by failing to mention any children from her five unions (Turner speculates that she might have used “birth control”).

Furthermore, Chaucer gives the Wife a career: “Of clooth [cloth]-makyng she hadde swich an haunt [skill] / She passed hem of Ypres and of Gaunt.” Scholars used to assume this meant she was a talented home-weaver (those piles of fine kerchiefs), but more recently economic historians have placed the Wife squarely in the booming 14th-century English wool trade as a textile entrepreneur, when, especially after the Black Death caused a labor shortage, women worked as key middlemen in a commercial economy in competition with the Low Countries. As Turner points out, Chaucer had a day job for many years as Controller of Customs at the Wool Quay in London, where he might have encountered loudmouth, tough-minded middle-aged women flaunting their economic independence by supervising and selling the output of cottage-industry looms.

A real-life Wife of Bath could conceivably have juggled operating a textile brokerage and managing her husbands’ extensive assets as well as their sex lives, but in Chaucer’s narrative she also has a third career: veteran professional pilgrim. Chaucer puts her on the road to Jerusalem and back not once but three times (the 2,500-mile journey from Western Europe typically took several months one way, on land and sea), and adds only slightly less arduous side-trips to Rome, Boulogne (which housed a revered image of the Virgin Mary), Cologne (site of relics of the Three Kings), and Santiago de Compostela. This is where the Wife of Bath seems to be a caricature of travel fever run amok.

Furthermore, the Wife demonstrates herself to be improbably learned for someone married off as a preteen—familiar enough with classical literature, the Scriptures, and the tracts of the Fathers of the Church to construct intricate and humorous arguments in her Prologue against the male authors of all of them, although often with a flair for misinterpretation that seems deliberate on Chaucer’s part. Just as the sole focus in the autobiography she provides in her Prologue is on her marriages (it is Chaucer, not she, who mentions her textile business), her sole literary focus is on literature about marriage—or rather, literature that tended to put her own robustly marital circumstances in a negative light.

So she takes on, besides Jankyn’s “wikked wyves” book, the apostle Paul, who counseled virginity and general sexual abstinence for Christians but famously if reluctantly conceded that it was better to marry than to burn. But Paul also maintained—to the Wife’s approval—that husbands and wives owed each other a duty to have regular sexual relations (the “marriage debt,” theologians have called it): “Let the husband render the debt to his wife, and the wife also in like manner to the husband,” in the language of the Vulgate Bible of the Middle Ages. The Wife of Bath summed this up in her typical ribald fashion:

Why sholde men elles in hir bookes sette

That man shal yelde to his wyf hire dette?

Now wherwith sholde he make his paiement,

If he ne used his sely instrument?

The Wife’s chief beef, however, is not so much with Paul as with the fourth-century church father St. Jerome.

Around the year 393, Jerome had composed a treatise condemning one Jovinian, a heretical theologian who maintained, contra Paul, that the state of virginity was no more exalted per se in the sight of God than the married state. In Against Jovinian, Jerome defended virginity as meriting a higher place in heaven for its adherents because it involved sacrificing the consolations of wedlock and offspring in order to devote oneself wholly to Christ. Then Jerome took a further step that infuriated the Wife. Never enthusiastic about wedlock in the first place, he argued that it was wrong for widows to remarry after their first husband’s death. “At the beginning, one rib was turned into one wife,” Jerome wrote of Adam and Eve. “And they two, he says, shall be one flesh: not three, or four; otherwise, how can they be any longer two, if they are several.”

Jerome didn’t go so far as to urge a complete ban on remarriage, which during his time and throughout the Middle Ages was commonplace, as disease and calamity left many young widows. But Jerome did place women with two or more successive spouses on a par with “penitent whoremongers”—to be welcomed like lost sheep but not admired. For the Wife of Bath, who insisted on being second to none even among her own sex, this was red meat (Chaucer relates that she became enraged if she was not first in line among the parish wives to bring up the offerings at Sunday Mass).

Finally, Jerome had rubbed salt into the Wife’s wounds by quoting extensively from The Golden Book of Marriage, a work supposedly written by the Greek philosopher Theophrastus, a disciple of Aristotle. The Golden Book was a polemic against marriage in general, which the author advised the “wise man” to avoid because it involved having to deal at close range with the foibles of women. Jerome quotes as follows about how irritating it can be to have a wife:

Matrons want many things, costly dresses, gold, jewels, great outlay, maid-servants, all kinds of furniture, litters and gilded coaches … [S]he complains that one lady goes out better dressed than she: that another is looked up to by all: ‘I am a poor despised nobody at the ladies’ assemblies.’ ‘Why did you ogle that creature next door?’ ‘Why were you talking to the maid?’ ‘What did you bring from the market?’

The Wife of Bath lists Jerome, along with “Theophraste” and other antifeminist writers from antiquity, as a chief contributor to Jankyn’s “wikked wyves” book, and she specifically mentions Against Jovinian. Indeed, her entire Prologue can be read as her sustained and acidulous diatribe against a single patristic treatise that annoys the life out of her. All this bickering over exegetical fine points contributes to the reader’s sense that the Wife of Bath is more a literary construction that satisfied Chaucer’s own intellectual preoccupations than a realistic fictionalization of someone Chaucer might have met at the Wool Quay.

The Chaucer scholar Jill Mann makes the case that the pilgrims of the Canterbury Tales are exercises in the genre of “estates satire,” in which stock characters embody humorously exaggerated stereotypes of their social types. The Squire is a fop, the Friar is a “wantowne,” the Monk spends his days hunting game with his greyhounds, the Prioress devotes more attention to feeding choice morsels to her pet lapdogs than to her prayers. The Wife of Bath seems to be an amalgam of a variety of female stock figures who were her literary antecedents.

One of the most obvious, as Turner notes, was La Vielle, an elderly ex-prostitute who narrates her life-story at length in the 13th-century French poem Le Roman de la Rose [the Romance of the Rose] that Chaucer had translated into English as a younger man. As Turner points out, the Wife of Bath straddles the line successfully between “mosaic” of her sources (Turner’s apt word) and a figure whose earthy diction, comic vernacular, and frank admission to every one of her faults propels the reader to enter the “illusion of interiority” that Chaucer has created for her, so that we see her as a rounded real person when she most decidedly is not.

This is where it is unfortunate that Turner, otherwise a perceptive and fine-grained analyst of Chaucer’s literary magic, becomes blinkered by the feminist rhetorical lens that she has chosen for reading the Wife’s Prologue and Tale. Not just the words “misogyny” and “patriarchy,” but wince-inducing 21st-century presentisms such as “rape culture,” “gender-fluid,” “queer and trans bodies.” Turner even quotes, “Nevertheless she persisted,” the Elizabeth Warren T-shirt motto. There is a perhaps obligatory reference to Thelma and Louise (although the Wife of Bath can think circles around those two ditzes), as well as potshots at Jordan Peterson and the fogey-traditionalist MP Jacob Rees-Mogg. This is material that will not age well.

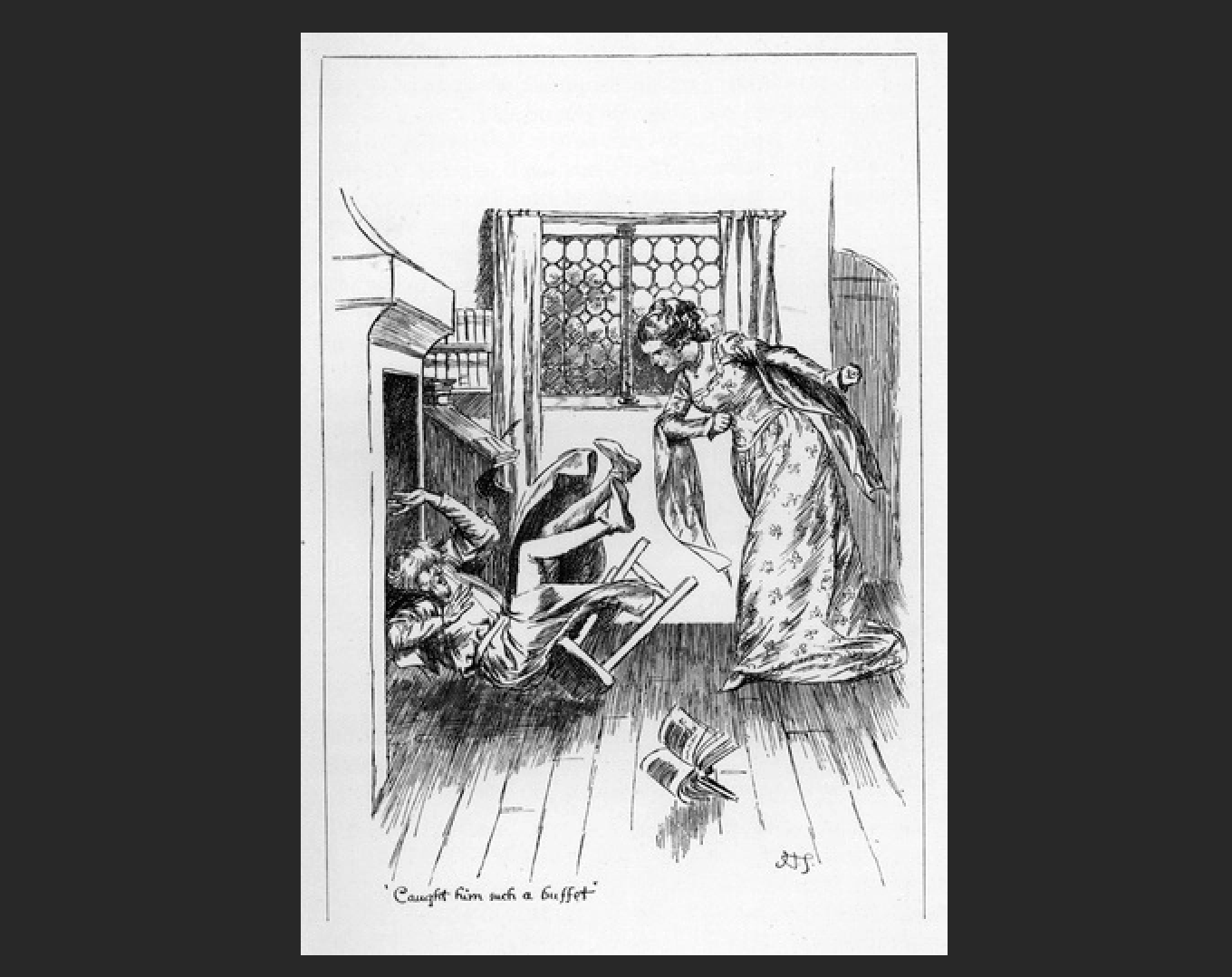

For example, Turner avers that the Wife is a “victim of domestic abuse” because her fifth husband, Jankyn, slugged her on the head during the “book of wikked wyves” fight and rendered her “somdel deef [deaf].” That sounds horrifying—except that Turner neglects to mention that it was the Wife who started the fisticuffs, as the Wife herself cheerfully admits in her Prologue.

As she tells it, she spots Jankyn reading his book while sitting by the fire, rips three pages out of it, and then hits him on the cheek so hard with her fist that he falls backwards into the fireplace. The enraged Jankyn then delivers his own blow. The Wife responds by pretending to be on the verge of death, and when an appalled Jankyn kneels by her side to blubber an apology, she slams him a second time. This is more Punch-and-Judy show than saga of a battered wife. The upshot, moreover, is that the Wife finally attains the “maistrie” that she craves over the now-humbled Jankyn: “He yaf me al the bridel in myn hond.” The artist who painted the Ellesmere miniature of her must have smiled at that.

When the Wife finally gets around to telling her Tale (which is only half as long as her Prologue monologue), it turns out to be an extension of the themes she explored in her autobiography. The story she tells is actually a charming one, a variation on the medieval fairy-tale motif of the “loathly lady” who rewards a knight’s kindness to her by magically transforming herself from ugly crone into beautiful young bride for him. The Wife of Bath gives this yarn her characteristic twist: The knight involved is a bounder who rapes a young virgin, a capital crime. When he is hauled into King Arthur’s court to have his head cut off, Queen Guinevere offers him a full pardon if he can come back in a year and a day with the answer to the question “What thyng is it that wommen moost desiren.”

The knight wanders for a year receiving unsatisfactory responses, and just as his reprieve is about to expire, he encounters the “loothly” lady (“foul, and oold, and poore”) who gives him the answer he needs to save his neck. Since this is the Wife of Bath’s Tale, it is, of course, “the maistrie.” But the old woman exacts a promise from him in return: he has to marry her. And also consummate the marriage. But as he is lying in bed with her wondering how he can go through with this, she offers him another magical deal: He can choose to have her “yong and fair” but faithless, or ugly as she is now but “a trewe, humble wyf.” The knight, either because he has learned his moral lesson, or because he realizes that “yes, dear” is sometimes the most prudent thing to say, tells her he is leaving the choice up to her. Delighted at this yielding of the “maistrie,” she rewards him by telling him that she will be both—beautiful plus virtuous—and he suddenly has a lovely young woman in his arms (“His herte bathed in a bath of blisse”).

Paradoxically, though, the end result of the knight’s having turned the marital reins over to his new bride is that “she obeyed hym in every thyng / That myghte doon hym plesance or likyng.” It is an echo (uncharacteristic for the Wife!) of the apostle Paul’s injunction in the Vulgate Bible: “Let women be subject to their husbands, as to the Lord.” It is a telling implication on Chaucer’s part that marriages, and relations between the sexes in general, aren’t simple impositions of masculinist patriarchy countered by feminist resistance, but involve a complex balancing of roles in which the sexes bend to each other in recognition of each other’s different natures.

The chief problem with an exclusively feminist reading of the Wife of Bath isn’t simply that such a reading isn’t amenable to nuanced interpretations. It’s that it never gets to the question of why Chaucer the author was so interested in anti-feminist literature that he constructed his most memorable Canterbury character as a mouthpiece for hundreds of lines of engagement with it.

For the ancient Greeks and Romans, admonitions against entanglement with both marriage and women in general constituted practically a literary genre of their own. Socrates’ biographers built Xanthippe into the nagging shrew who empties a chamber pot over her husband’s head. Ovid, in his Ars Amatoria, advised men who sought success with the fair sex never to forget their birthdays or ask them their ages. Juvenal devoted one of his Satires to warning men that their wives were likely to overspend them into penury, quarrel at the drop of a hat, go gaga over actors and musicians, and present their husbands with offspring to whom they might not be biologically related. Today’s expression “black-swan event” derives from Juvenal’s likening of the exceedingly rare worthy wife to that exceedingly rare bird. Theophrastus might not have actually written The Golden Book of Marriage (which was more likely composed several centuries after his lifetime), but the cynical portrait of wives that the book painted derived ultimately from the thought of Theophrastus’ teacher, Aristotle, who asserted that women were imperfect, emotion-ruled versions of men.

The admonitory literature of the ancients dovetailed with Christian teaching about the superiority of consecrated virginity, especially for writers such as Jerome who only grudgingly approved of marriage in the first place. Accordingly, the Middle Ages witnessed a vast amplification of antifeminist and anti-marriage literary themes: works such as The Fifteen Joys of Marriage, which describes wedlock as “a confining, sorrowful, and tearful prison,” and Le Roman de la Rose, which declares that if a man takes a beautiful wife whom other men desire, she will inevitably be unfaithful—but if he selects for ugly, she not only will look repulsive but will ultimately betray him as well. Much medieval light reading consisted of fabliaux: off-color yarns about cuckolded husbands and bastards passed off as legitimate.

This was writing that was indisputably misogynist, so much so that Chaucer’s female contemporary, the Venice-born French poet Christine de Pizan, protested vigorously and produced her own work in 1405, The Book of the City of Ladies, hailing virtuous queens and other female heroines. The Wife of Bath complains:

By God, if wommen hadde writen stories,

As clerkes han withinne hire oratories,

They wolde han writen of men moore wikkednesse

Than al the mark of Adam may redresse.

A fair enough criticism. But there were other reasons for the lasting popularity of antifeminist literature besides a male-dominated society’s imposition of patriarchal values. For one thing, underneath the exaggerations of the ancients and medievals, there is a grain, and often a sand-dune, of truth. The Golden Book of Marriage may be hyperbole, but there is something uncomfortably close to home about its characterization of women’s preoccupation with clothes, home furnishings, and status competition with other women, especially over the men they deem desirable. All you have to do is dip into the most perceptive chick-lit—Jane Austen, Muriel Spark, Wendy Wasserstein—to find its female authors in essential agreement with “Theophraste” (i.e., Theophrastus). Here is Aristotle, in his History of Animals:

Hence woman is more compassionate than man, more easily moved to tears, at the same time is more jealous, more querulous, more apt to scold and to strike. She is, furthermore, more prone to despondency and less hopeful than the man, more void of shame or self-respect, more false of speech, more deceptive, and of more retentive memory.

Well, yeah.

The Wife of Bath’s Prologue and Tale is a story about the battle of the sexes, so different from each other in interests and temperament as well as physical appearance that they find each other incomprehensibly baffling. Antifeminist literature is in fact a record of the paradox of male bafflement by women: Why are they so irritating, so full of complaints, moods, laughable foibles, and obvious weaknesses—yet we men tie ourselves to them for life and want to die ourselves when they die.

Antifeminist polemic is essentially a comic genre, characterized by the exaggerations of standup. It is a comic genre that has persisted to this day, or at least until the day before yesterday: “Take my wife … please,” Andy Capp’s Flo chasing him with a rolling pin, H.L. Mencken’s remark that women are “the only grand hazard a man will truly encounter,” the “ways of women” bewilderment in the 1990s “Lothar of the Hill People” sketches on Saturday Night Live. Of late, “That’s not funny!” feminism has pretty much killed off this genre. Washington Post writer David Weigel got suspended in 2022 for retweeting this joke: “Every girl is bi. You just have to figure out if it’s polar or sexual.” But there were plenty of people whose lips twisted in wry smiles of recognition—that is, if they didn’t laugh out loud.

Every girl is bi. You just have to figure out if it’s polar or sexual.

— Cam Harless (@hamcarless) June 2, 2022

Chaucer clearly found this sort of invective fascinating because he found relations between the sexes fascinating. Scholars of past generations used to try to isolate a “marriage group” in the Canterbury Tales, finding a sequence of tales (including the Wife of Bath’s) that contrasted ideas of male and female sovereignty and equality in wedlock. In fact, nearly all the Canterbury Tales are about marriage, examining it from a range of angles and perspectives positive and negative. Husbands push their wives around, frisky wives pin horns on their husbands, wives and husbands show touching loyalty to each other, suitors battle each other to the death for maidens’ hands, maidens pointedly wish not to marry at all.

Themes from Jerome’s Against Jovinian and Paul’s epistles appear in other Canterbury Tales material besides the Wife of Bath’s. “Theophraste” makes an appearance in the Merchant’s Tale, whose theme is literally January-May cuckoldry (the husband and wife are named “January” and “May”). The Shipman’s Tale is an R-rated word-play on the concept of the “marriage debt”: it involves a monk who sleeps with a merchant’s wife after borrowing money from her husband to pay off her bills and then skips town after telling the husband he has repaid the loan to the wife; when the husband asks the wife what happened to the money, she says she spent it on clothes but will repay him in bed.

In fact, the Wife of Bath herself embodies all of the negative stereotypes about women in which “Theophraste” and others indulged. She cannot stop talking—and arguing with—whomever she encounters, whether in books or real life. She’s a clotheshorse par excellence. She can’t stand to be criticized (“I hate hym that my vices telleth me”). Nor can she stand to be anything other than the alpha among the parish wives. She lusts after Jankyn exactly because he is “daungerous” (standoffish) and makes her chase him rather than vice versa (“We wommen … crave … what thyng we may nat lightly have”). Indeed, Jankyn seems to have been an early avatar of the “game” seduction theorists of the early 21st century manosphere who argued that the surest way to get a woman into bed was to dish out “negs,” subtle digs about their looks, that made them yearn for signs of approval.

The Wife’s scriptural exegesis is shaky; she miscounts the number of domestic partners of the Samaritan woman whom Jesus encounters at a well in the Gospel of John so as to make that number match her own. And unlike nearly all the rest of the narrators in the Canterbury Tales, she cannot tell her Tale straight without numerous digressions in which she slips—amusingly, it must be said—right into her garrulous Wife of Bath persona. She takes a little poke, for example, at the lecherous Friar, who has interrupted her by criticizing her “long preamble” of a Prologue. She nearly sabotages herself by inserting, for no discernible reason, a story from Ovid’s Metamorphoses in which the wife of King Midas just has to tell somebody that her husband is hiding under his long hair the fact that he has asses’ ears—so she tells the river, which, according to Ovid, bruits it to the world via its flowing ripples. We women “kan no conseil [secret] hyde [hide],” the Wife blithely declares, apparently unaware that she is echoing the very antifeminist literature that she claims to disparage.

And yet—how is it impossible not to love the Wife of Bath, warts and all? In Against Jovinian, Jerome compared virginity to the finest wheat, whereas the married state to Jerome was coarse, humble barley, better eating than “cow-dung” but inferior food nonetheless. But as the Wife points out, there would be no virgins if there were no wives to bring them into the world: “And certes, if ther were no seed ysowe, / Virginitee, thanne wherof sholde it growe?” She points to a favorite Gospel story in which Jesus miraculously feeds 5,000 men with just five loaves and two fishes:

Inyl envye no virginitee.

Lat hem be breed [bread] of pured whete-seed,

And lat us wyves hoten [be called] barly-breed;

And yet with barly-breed, [the evangelist] Mark telle kan,

Oure Lord Jhesu refresshed many a man.

She gets it a little wrong: It was the evangelist John, not Mark, who specifically mentioned that the loaves were made of barley. But that’s the Wife of Bath. And the bottomless layers of allusion are lovely: the fertility, the nourishment, the growth from seed to fullness, and from the lowliness of barley to the refinement of wheat, the multiplication of blessings in the form of children. What better defense of the wifely state? Chaucer clearly thought the Wife of Bath was a wonderful creation, walking the line between “literature and life” in Turner’s words. So do we.