Nations of Canada

Up the St. Lawrence

In the fifth instalment of an ongoing Quillette series on the history of Canada, Greg Koabel describes Jacques Cartier’s first encounters with the Mi’kmaq and Iroquois.

What follows is the fifth instalment of The Nations of Canada, a serialized project adapted from transcripts of Greg Koabel’s ongoing podcast of the same name, which began airing in 2020.

The last instalment in this series left off in 1509, on the eastern side of the Atlantic, with Henry VIII taking the English throne after the death of his father, Henry VII. This new Henry ended up being one of the dominant figures in English history. But this is one of those rare narratives that is going to ignore most of what he got up to. For the next few decades, England and its king would have bigger things to worry about than the question of who controlled the fishing grounds on the other side of the ocean.

Our story will shift across the English Channel, to France, which, till now, has not featured prominently in the North Atlantic colonial rivalry. Unlike their English counterparts, French fishing fleets were well-supplied with salt, and so were not dependent on dry land to preserve their cod (i.e., they could process the catch onboard their ships). As a result, the French were not affected by the closure of Iceland’s ports, nor were they desperate to find new lands as the English were.

At first, the French weren’t all that concerned about European rivals such as England or Portugal making claims to the icy rocks they’d found on the other side of the ocean either. The initial voyages made by John Cabot and Gaspar Corte-Real seemed to vindicate this lack of interest. Despite visions of profitable Oriental trade, none of those voyages produced anything of real commercial value.

Of course, French fishermen got word of the seemingly endless supply of cod off the coast of Newfoundland, and joined the bonanza on their own initiative. But the French state itself saw no pressing need to involve itself in such trivial matters.

By the 1510s and 1520s, however, French attitudes began to change—thanks to events taking place much further south, where the Spanish were starting to reap the benefits of their New World discoveries.

While neither Columbus nor Cabot had found a passage to the Orient, over time, Columbus’s voyages, unlike Cabot’s, eventually brought a return on investment. In fact, his Spanish sponsors enjoyed a double success, both elements of which were realized simultaneously.

The first was the discovery that the part of the New World claimed by the Spanish contained unimaginable reserves of gold and silver. From 1519 to 1521, a Spanish conquistador named Hernán Cortés led a military campaign to secure those reserves. Cortés managed to conquer the Aztec Empire in modern-day Mexico, creating a source of wealth that would drive the Spanish empire for centuries to come. The later conquest of the Inca in the 1530s opened up even more lucrative silver mines in the Andes.

The second success the Spanish enjoyed was the discovery of a passage through the American continents to Asia: At the same time Cortés was battling the Aztecs, Ferdinand Magellan led the first voyage around the southern tip of South America, and reached the coveted markets of the Orient.

In other words, not only had the Spanish found the long-sought passage to the Orient, they’d also found a previously unknown source of wealth along the way. This dual good fortune had the potential to transform Spain into a global superpower—perhaps one strong enough to brush aside any European rival.

For the French, who already fancied themselves a great European power, this was a most unwelcome development.

If France wanted to keep pace with Spain, the French would have to act quickly. Their options were limited, however. The Spanish already had a permanent presence in the New World. It would be difficult to dislodge them from the gold and silver mines they controlled, and any French ships attempting to follow Magellan would be vulnerable to attack.

So, if the southern route was blocked, what of the northern route? The French knew that English fleets had tried it, under William Weston in 1499 and Sebastian Cabot in 1508. No one in France knew exactly what those voyages had found, but judging by the fact that England had not followed up, it was unlikely they had gotten far. All reports indicated that the only thing north of the fishing grounds in Newfoundland were storms and ship-breaking ice bergs.

As for Newfoundland itself, the window of opportunity seemed to be closing. The Portuguese were already setting up a permanent base to service their fishing fleet in Newfoundland. It was a far cry from a military installation, but unless the French built up a presence of their own, they might soon find it difficult to travel anywhere on the far side of the Atlantic.

And so, by 1523, the 29-year-old French king, Francis I, decided on a middle passage. Through his agents in Spain, Francis knew that the Spanish had explored as far north as Florida. Between that and Newfoundland there was a 1,500 km blank space on the map. Might there be a gap that might lead to the Orient?

Of course, it’s possible that John Cabot had already sailed down the Atlantic coast of North America, disproving that thesis. But (a) the evidence that Cabot did so is well short of definitive; and (b) if Cabot did explore the Atlantic coast, it was not common knowledge at the time. What this means is that, for all anyone knew—including Francis I—Columbus and Cabot had discovered two separate land masses. If there was a path between them—a middle passage—it was likely to be more direct and less dangerous than Magellan’s long detour, or the icy waters to the north.

Francis commissioned a Florentine navigator named Giovanni de Verrazzano to fill in that blank stretch of map and, if possible, locate a middle passage. Although Italian, Verrazzano had been based in the French port of Dieppe since around 1506. Like their counterparts at other French ports, such as St. Malo and La Rochelle, fishermen from Dieppe had been quick to join the cod bonanza off Newfoundland. Verrazzano had taken part in these seasonal voyages multiple times, and had already mapped out portions of the Newfoundland coast.

In the fall of 1523, Verrazzano set out in the direction of Newfoundland with four ships, but was almost immediately forced to turn back when a powerful storm damaged his fleet. Repairs further delayed him until December, and Verrazzano was hesitant to brave the North Atlantic in winter. The storm he’d gotten caught up in marked the beginning of the stormy season in the north, a dangerous time for sailing vessels.

Avoiding natural dangers, Verrazzano decided to brave human dangers and cross in the southerly waters frequented by the Spanish and Portuguese. Luckily, he avoided detection and crossed the Atlantic without incident, landing in modern-day North Carolina in March 1524. Feeling that he was already too close to the southern Spanish settlements for comfort, Verrazzano decided to follow the coast north.

Through the spring of 1524, Verrazzano moved up the coast, past Chesapeake Bay (which he seems to have missed), around Long Island, into New England, before arriving in the familiar waters of Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. Although Verrazzano did map a huge swathe of coastline, the voyage was a disappointment. The primary goal—the discovery of a middle passage—was not met. When Verrazzano arrived back in France in July 1524, he reported his findings to a disappointed King Francis. There was no easy passage through the New World. France would have to find a different way to counter Spanish power.

Verrazzano would lead two more expeditions in the following years (one to Brazil, and one into the Caribbean), but in the absence of a direct passage to the Orient, the French Crown lost interest. Verrazzano himself likely died in 1528, while on his third voyage, possibly killed by locals on the island of Guadeloupe.

As for King Francis, his attention was pulled away from the Atlantic in the years after Verrazzano’s voyage anyway. His relationship with Spain had turned from great-power rivalry to all out war. The French King’s archenemy became the Hapsburg Charles V, who was both Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain. Throughout the 1520s, the two leaders battled for control of Italy.

And things did not go well for Francis. At the Battle of Pavia (fought just months after Verrazzano returned from America), the French army was defeated, and Francis himself captured by the enemy. In the resulting peace, Francis was forced to accept humiliating terms from Emperor Charles. The French king, however, was not one to give up. And as soon as he was released, he repudiated the peace he had signed and re-opened the war. This time, he had the support of the Pope (who hoped to prevent Hapsburg domination of the Italian peninsula).

The ins and outs of European power politics are not what we’re here for though, so I won’t delve into the Italian wars any further.

The important point for us is that by the 1530s, Francis was allied with the Pope, which had implications for France’s New World strategy. The 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas, which had divided the globe between Spain and Portugal, was backed by Papal sanction. Francis had always been hesitant to alienate the Papacy by violating the agreement too flagrantly. But now that he and the Pope shared an animosity towards the Hapsburgs who ruled Spain, Francis was more confident that he could involve himself in New World affairs with impunity.

And the timing was good, because reports from the European fishermen who frequented the shores of Newfoundland had re-ignited hopes of a middle passage.

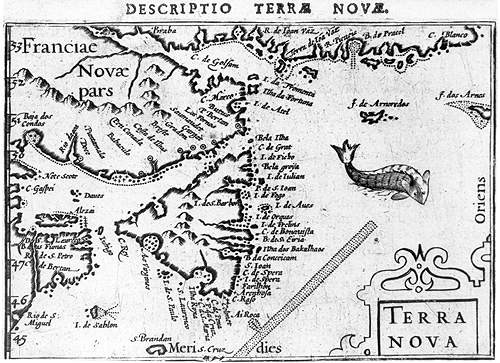

A full generation had passed since the initial discovery of Newfoundland and its cod. During that time, the fishermen had gotten to know the land quite well. Competition was stiff every summer, and the best fishing grounds filled up quickly. Some crews took to poking around, in search of new places to drop a line. This was especially true of French fishermen, who had been late arrivals to Newfoundland in comparison to their English, Portuguese, and Basque competitors.

We don’t know for sure what information was filtering back to France. These men had an incentive to be secretive about any new fishing grounds they’d discovered. But it gradually became apparent that Newfoundland was an island, and that a great expanse of water lay on the other side of it. This, of course, was the Gulf of St. Lawrence (though, of course, it would not be known by that name for many years). Who knew what lay on the other side of this open water?

The man destined to discover what lay beyond the Gulf was Jacques Cartier, a pilot and navigator from the port town of St. Malo in Brittany.

When Cartier was born, in 1491, Brittany was not a part of France, but an independent Duchy. In that same year, however, Charles VIII of France used force to induce Anne, the Duchess of Brittany, into marriage. From then on, French kings claimed the title of Duke of Brittany as their own; and in 1530, Francis I formally brought Brittany into the French state.

Yet the Breton identity (as distinct from the French) was still strong—which was not anomalous: As we’ll see in future instalments of this series, regional French identities would remain a lot closer to separate national identities for generations to come.

I bring this up now, in introducing Cartier, because most of the Frenchmen we’ll encounter in this Canadian story came from one of three distinct coastal regions in modern France: (1) The ports of Normandy, which linked directly to Rouen on the river Seine (and from there on to Paris); (2) St. Malo, the most important of the Breton ports; (3) and the salt producing ports on France’s western coast, led by La Rochelle. You could also include a fourth region here, the French controlled portion of the Basque country, with its main port of Saint Jean de Luz.

We’ll get to know each of these regions in the future. French commercial and colonial projects in Canada will be defined by (and in some sense undermined by) the relationships and rivalries between Rouen, St. Malo, La Rochelle, and the Basques.

But, back to our man of the hour. Jacques Cartier was the son of a well-respected pilot in St. Malo (a position of relative prestige in a bustling port town). He followed in his father’s footsteps, and by 1520 had done well enough to marry above his station—the daughter of a prominent merchant in town, Mary Catherine des Granches. It’s possible that three years later (at the age of 32), Cartier joined Verrazzano on his trip to the American coast (though the evidence is not definitive). It’s also possible (bordering on very likely) that Cartier travelled to Newfoundland in the 1520s. Every summer, several ships from St. Malo set out for Newfoundland cod, and it would have been entirely natural for a well-regarded navigator like Cartier to tag along.

Whether Cartier had seen the far side of Newfoundland for himself, or merely heard about it from the sailors and mariners he’d spent his days with, by the early 1530s he was convinced that this body of water was worth exploring. His experience with Verrazzano (assuming he actually did travel with the Italian) suggested that there might be interest within the French royal court too. Maybe Verrazzano had been too quick to give up on the middle passage.

Cartier’s opportunity to find support for his project came in 1532 when King Francis visited the abbey of Mont St. Michel, just 35 km east of St. Malo. You’ve probably seen pictures of Mont St. Michel even if you haven’t heard the name. It’s a walled medieval complex that, at high tide, is totally surrounded by the English Channel. Much like tourists today, King Francis was dropping by to see the sights, and pay his respects as a humble pilgrim.

Cartier’s in with the King came via Abbé Jean le Veneur, the Abbot of Mont St. Michel and a distant relative of the Cartier family. Veneur vouched for Cartier by pointing out his experience—his (presumed) voyage with Verrazzano and other (also presumed) trips across the Atlantic. Veneur sweetened the pot by offering for the Church to pay half the costs of the expedition, and help securing a formal declaration from the Pope that the Treaty of Tordesillas did not apply. The project also seemed to be tied up with a marriage between Francis’s second oldest son, the future King Henri II, and the Pope’s niece, Catherine de Medici.

As a result, Cartier’s project existed on the periphery of European dynastic and Church politics.

In 1534, Francis commissioned Cartier to set out with two ships and more than 60 men. However, as John Cabot had discovered in Bristol, things got a little complicated when it came to the logistics for this sort of project. The fishermen of St. Malo were not enthusiastic about an official voyage to map their secret fishing grounds around Newfoundland. They organized a boycott among the mariners and outfitters in St. Malo, and Cartier could not find the sailors or supplies he needed. It took a sternly worded letter from the King to convince the reluctant mariners to help out.

Ultimately, Cartier got his men. But the pattern would repeat itself in the future. The interests of the French state did not always match the interests of France’s various trading ports or merchant communities. Successfully negotiating those varied interests would be difficult, but also necessary if the French colonial project were to thrive.

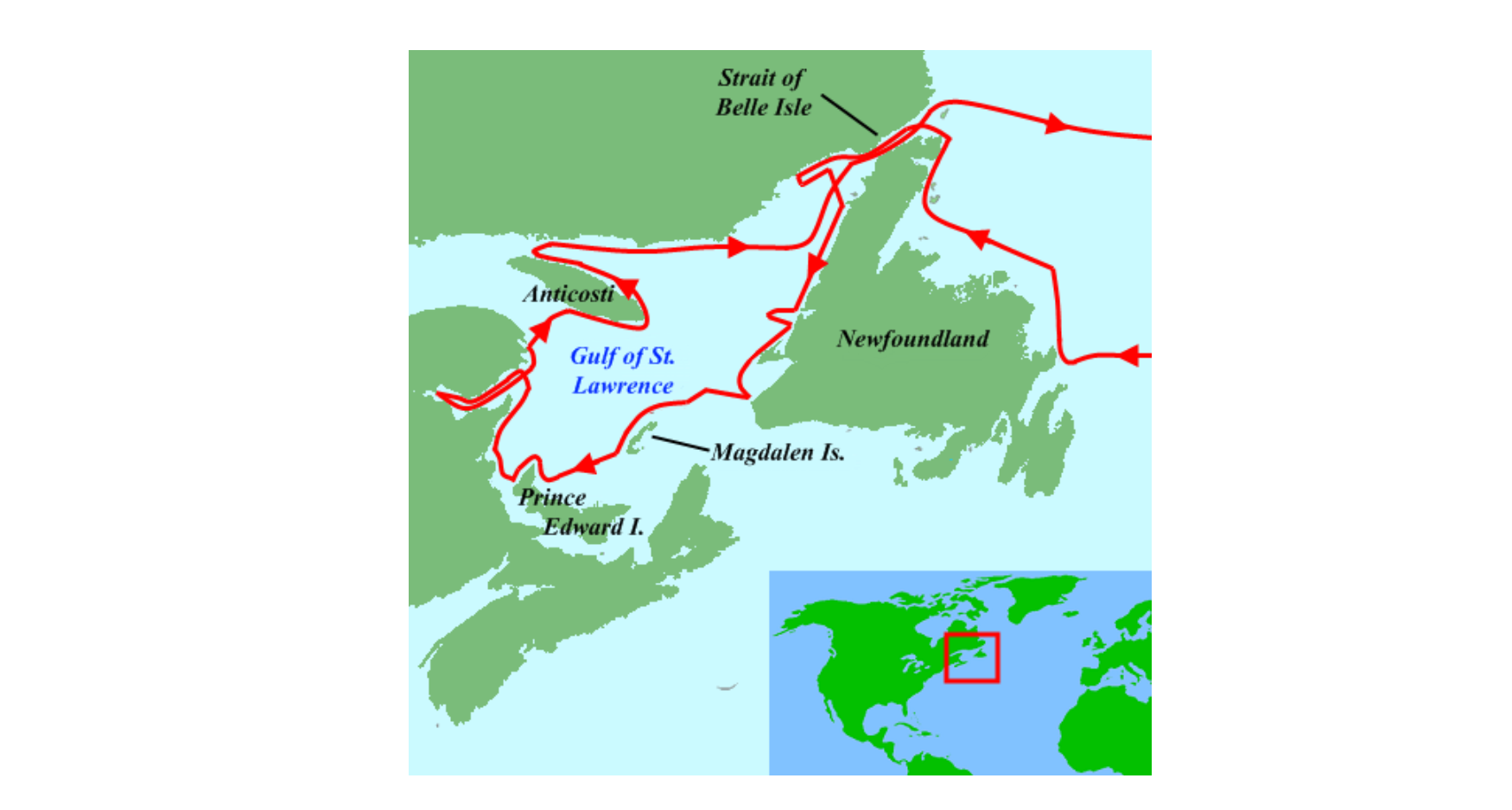

With the mariners of St. Malo sufficiently cowed, Cartier set out on April 20th, 1534. The crossing (which Cartier and most of his crew had likely completed before) was quick and uneventful. In the second week of May, they arrived at Cape Bonavista on the Atlantic coast of Newfoundland. It was extremely early in the summer fishing season, and the sea was still full of massive, and dangerous, chunks of ice. Cartier had likely left as early as possible, so as to maximize the time he had to explore. But until the ice cleared, safety came first. For 10 days, the ships remained anchored in a natural harbour (likely one well known to veterans of the cod fishery Cartier had with him).

Once Cartier was ready to move, he headed north. The Strait of Belle Isle, the narrow gap between Labrador and the northern finger of Newfoundland, was well known to Europeans, and a safer way around Newfoundland than the less well known southern route. In fact, the strait was one of the busiest places in the area during the fishing season. It was the best whaling ground then known to Europeans, and the Basques (who were Europe’s premier whaling specialists) congregated there every season.

It was still early in the year though, and the narrow strait had too much ice for Cartier’s taste, so he spent the end of May and first days of June charting the Labrador coast north of the strait. Cartier was unimpressed with the rocky, inhospitable shore, and named it “the land God gave to Cain” (la terre que Dieu donna à Cayn). The experience only validated Cartier’s belief that the true passage lay to the west, not through the barren north that surely only got worse the further you went.

After a few days of this, Cartier was confident enough to push through the strait. Within a couple days, they were through and heading west along the coast of modern day Quebec. The speed with which Cartier moved through these narrow waters suggests that he had pilots who had navigated the strait before. Indeed, a significant part of Cartier’s mission was to chart land that was only known to Europeans through the memory of veteran pilots.

This sense that Cartier was travelling in waters that were familiar to Europeans was confirmed on June 12th, when he encountered a fishing vessel out of La Rochelle about 100 km west of the Strait of Belle Isle. Clearly, French fishermen were well aware of the existence of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Cartier had not yet entered totally alien waters, but he was close.

Two days after meeting the Rochellois, Cartier turned into the open ocean to the south. His goal appears to have been to definitively prove Newfoundland was an island. He achieved this by hitting the west coast of Newfoundland, then following it south until he hit the Cabot Strait that separates Newfoundland from Nova Scotia. Once the ships sighted land on the other side, Cartier had confirmed that Newfoundland was passable from both the north and the south.

On July 6th, Cartier made contact with the local inhabitants on the mainland coast. As Cartier and a handful of others were approaching the shore in a rowboat, they suddenly sighted several canoes heading in their direction. Those who weren’t paddling were holding up long sticks, with various animal pelts on the ends of them. By their gestures, it seemed clear that these men were offering furs to the French explorers in exchange for other goods. Cartier had encountered a trading party of Mi’kmaq, an Algonquin-speaking people who resided in Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and northern New Brunswick.

Two things are evident from this initial meeting. First was the fact that these were not the first Europeans the Mi’kmaq had encountered. In fact, a generation of seasonal fishing had made Europeans a familiar sight in the region.

We’ve already seen that the Beothuk of Newfoundland reacted to the presence of Europeans by retreating inland to avoid them—an understandable response since first contact with the Portuguese had taken the form of a mass slave raid. But for most of the other people living on the east coast of Canada, the annual influx of European fishermen was a welcome opportunity for trade. For the Mi’kmaq (or the Innu, another Algonquin-speaking group that populated Labrador and the north coast of the Gulf of St. Lawrence), the arrival of the European ships each year meant valuable iron tools or copper kettles, which could be had for old fur coats or easily obtained animal skins.

Cod wasn’t the only thing the Europeans were bringing back from Canada. The fur trade, which eventually would come to dominate the Canadian economy, had already started by the time Cartier arrived—albeit as a side-business that fishermen engaged in. At the moment, none of the Europeans were coming to Canada for the exclusive purpose of purchasing furs, as the market was not yet sufficient to support that scale of trade. But the process had begun.

The second lesson to draw from Cartier’s encounter with the Mi’kmaq was that (like the Norse), the French were extremely cautious when it came to the indigenous populations they came across.

When the would-be traders approached Cartier’s rowboat, he and his men made their own gestures, frantically urging the Mi’kmaq to keep their distance. Cartier was only comfortable speaking with the Mi’kmaq in a controlled environment. And standing in a rowboat with a couple of aides, surrounded by canoes, was not his idea of a controlled environment.

At first, the Mi’kmaq ignored Cartier’s hand waving. Who could say what this oddly dressed fellow was trying to communicate? As long as there was the chance of scoring some metal tools, they pressed on. However, when one of the ships fired two warning shots with a cannon, the fur salesmen got the message and backed off.

The next day, the two sides met again, this time with Cartier and his men safely aboard their ships. The Mi’kmaq offered furs, in exchange for various trinkets and whatever scrap metal the French didn’t need.

With the southern passage around Newfoundland confirmed on his map, Cartier decided it was time to press westwards across the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Now, almost certainly, he was heading into waters no European had entered before.

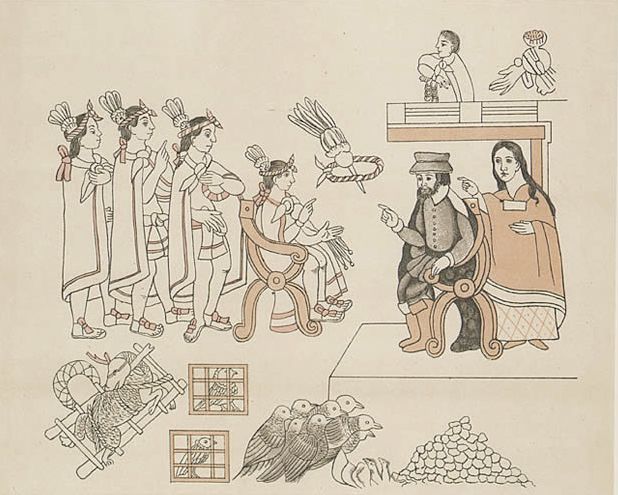

On July 20th (about two weeks after his encounter with the Mi’kmaq), the expedition landed on the Gaspé (the bulging peninsula that marks the southern coast of the St. Lawrence’s mouth). Once again, Cartier came across a group of locals. However, unbeknownst to him, these were an entirely different people than the Algonquin-speaking Innu or Mi’kmaq that Europeans had been trading with for decades. These were Iroquoian speakers who had come down the St. Lawrence River to the sea. As far as we know, this was the first encounter between Europeans and the Iroquoians.

Most of the Iroquoian-speaking societies (the Confederacies of the Wendat or the Iroquois for instance) were based around the Great Lakes, more than 1,000 km from the Gaspé Peninsula. But the eastern margins of Iroquoian culture stretched down the St. Lawrence as well. There were significant settlements at Hochelaga (near modern-day Montreal) and Stadacona (near modern-day Quebec City).

Cartier was meeting the residents of the easternmost settlement, Stadacona. Stadacona existed as a kind of hybrid indigenous village. It was occupied all year round, and the women of the settlement grew corn. But Stadacona also had one foot in the more nomadic world of the Algonquin-speaking hunter/gatherers: Every summer, a large segment of the village travelled down river, to traditional fishing grounds at the mouth of the St. Lawrence. In a sense, the Stadaconans Cartier met were doing the same thing the European fishermen were doing off the coast of Newfoundland—gathering seasonal resources.

For the French, the first clue that these were different people than the Mi’kmaq was that they had no furs to trade. Over 200 people were packed into 40 canoes. This was a mobile village, not a trading party.

However, even if the Stadaconans did not come prepared to trade, they greeted the Europeans warmly. Archaeological evidence suggests that the European goods being traded on the Atlantic coast were slowly trickling westwards through pre-existing trade routes. The Stadaconans also interacted with the Innu, the Mi’kmaq, and other Algonquin-speakers while on their annual fishing trip. So although the Stadaconans had probably never met a European before, they were likely aware of them, either through rumour or their goods.

Cartier, still wary, would meet with the Stadaconans only in equal numbers, close to the ships and well away from their main group. Among the small group of Stadaconan representatives, Cartier quickly identified a man named Donnacona as the leader (though, at this point, Cartier, like all Europeans, was entirely ignorant of Iroquoian political structures). Donnacona was a civil chief, who represented his clan-segment and the Stadaconan village council, but had no authority as a Frenchmen would understand the term. He could not coerce his fellow villagers, only persuade them.

For now, this distinction didn’t matter in the rather rudimentary communications the two men muddled through. But the mutual misunderstanding of political systems would come to define Franco-Iroquoian relations in the years to come.

Following an initial exchange of gifts to demonstrate goodwill, Cartier’s unease was somewhat alleviated. In fact, he was soon confident enough to erect a cross, formally claiming the territory in the name of King Francis I.

This produced the first real tension between the two groups. Donnacona may not have understood French, but he felt he had a good sense of what this strange monument meant. In another carefully controlled meeting, Donnacona berated Cartier for infringing on Stadaconan hospitality. As far as he was concerned, the earlier exchange of gifts had been a recognition that the French were guests on traditional Stadaconan land. Cartier’s construction of a monument without permission was a rude violation of that hospitality.

Donnacona was especially sensitive to such an intrusion because the previous year, a group of Stadaconans heading out to the Gaspé had been massacred by a group of Mi’kmaq. Defending territorial claims was no trivial matter.

Cartier managed to defuse the situation by explaining (disingenuously) that the cross was merely a navigational beacon, to ensure French could return to the same spot and trade with the Stadaconans in the future. This (along with another round of gift exchanges) placated Donnacona.

What happened next is somewhat more difficult to parse. Donnacona and a few others (including two of his sons) boarded one of Cartier’s ships to further celebrate their new relationship. This would be a pattern repeated in future Franco-Iroquoian relations: Alliances were not considered official until each party had played host to the other.

While the Stadaconan party was on board his ship, Cartier proposed that he take some of them with him back to France. He was likely hoping to spend the winter teaching French to a few Stadaconans so that they could act as translators in another voyage the following summer. Cartier selected Donnacona’s two sons (Domagaya and Taignoagny) as suitable candidates. The account we have is from Cartier’s perspective, and is no doubt muddled by the rudimentary attempts at translation on both sides, so it is far from clear what Donnacona thought of this.

The most likely scenario is that the Stadaconans were not enthusiastic about this plan, but were willing to accept the French fait accompli when Cartier did not allow the two young men to leave the ship.

Although Donnacona was probably not happy about the arrangement, he appears to have been able to live with it. The exchange of young men was a common feature in trade alliances between indigenous communities. Domagaya and Taignoagny living among the French for a period of time would have been a familiar step in cementing a relationship with a new ally. The only part of the arrangement that was unusual was that no Frenchmen reciprocated by offering to stay with the Stadaconans.

Donnacona was motivated to overlook this irregularity by two factors. First, the massacre of Stadaconans at the hands of the Mi’kmaq the previous year weighed on his mind. These newcomers had the potential to alter the balance of power in the region. An alliance with the French might act as a shield against further attacks. Moreover, if Donnacona alienated Cartier, he risked pushing the French into the arms of the Mi’kmaq (who he knew already had some form of trading relationship with the Europeans). This was a delicate diplomatic game of risk and reward.

Secondly, Donnacona and the Stadaconans were probably intrigued by the possibilities of European trade goods—in particular, iron and copper. More importantly, beyond Stadacona lay the upper St. Lawrence and the Great Lakes Confederacies. The Stadaconans were perhaps not thinking at this high strategic level at this point; but the trade relationship with the French had the potential to be enormously beneficial, especially if they could maneuver themselves into being the middlemen for the entire Great Lakes region.

Whatever reasons the Stadaconans had for accepting Cartier’s quasi-abduction of the two young men, they still seemed to be anxious about the situation. As Cartier’s ships sailed away from shore, dozens of canoes moved alongside the ship, frantically throwing food on board. Whether this was meant to be a ransom for the release of the two prisoners, or provisions for their time abroad, is not entirely clear.

Once into the Gulf, Cartier headed north and then east, toward the Strait of Belle Isle (the route back to the Atlantic that he was most familiar with). It was August now, near the end of the fishing season. Ice would soon make sea travel dangerous, and no one wanted to spend the winter in Canada. Upon entering the strait, Cartier was warned by the Innu there that all the other Europeans had already gone home for the year. The episode underscores the familiarity between the European fishermen and the Algonquin-speakers along the coast: These Innu were familiar enough with European practices, and European languages, to relay fairly complex information to the French crew.

By September 5th, Cartier and his two ships were back in St. Malo, having spent about four-and-a-half months at sea. The voyage was a resounding success. First of all, Cartier had mapped much of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Previous knowledge of the region among Europeans had been a mixture of rumour and the closely guarded secrets of fishing crews.

Secondly, Cartier had a credible lead on the elusive middle passage. While on the return voyage, Domagaya and Taignoagny provided a more detailed assessment of their homeland. Cartier was particularly interested in the great channel the village of Stadacona sat on. The brothers claimed that it cut deep into the continent, well beyond their own village. On the other end were great bodies of water, and wealthy, powerful nations.

These reports could not have been better tailored to spark excitement in Cartier and his backers at the French court. By this time next year, French traders might be in the Orient, neutralizing Spain’s global advantage.

Almost immediately, plans were in the works for another voyage the following year. Royal backing was assured once Domagaya and Taignoagny repeated a carefully designed version of their tale to the King. They described a great western waterway that led to cities of unimaginable wealth. Likely Cartier and his backers coached them to present this in terms that resembled the Orient. Or perhaps the brothers were canny enough to understand what the French wanted to hear. After all, the more interested the French were in their homeland, the quicker they were likely to get back there.

It’s unlikely that the two brothers enjoyed their time in France—especially since they went through a crash course in the French language in order to serve as translators on the return voyage. In the following years, indigenous Canadians would express an almost universal revulsion to European education techniques. Coercion, authoritarianism, and strict discipline, staples of a European education, were alien (and indeed abhorrent) to most indigenous cultures.

The brothers did seem to pick up an affinity for European clothing, however, and continued to wear French styles even after their return home.

And that return voyage across the Atlantic could not come quick enough, for the Stadaconan brothers, or for Cartier himself. Like John Cabot thirty-odd years before, Cartier fancied himself on the brink of becoming another Columbus. And unlike Cabot, Cartier had made some genuinely promising discoveries in the New World.

He had made contact with an indigenous population quite different from the Algonquin-speaking peoples that European fishermen had been having dealings with for decades. The existence of the Stadaconans hinted at more advanced civilizations further west.

For Cartier, this was something just as tangible as the initial Spanish discoveries had been. And he was determined to realize that potential. Next time, Cartier would have trained interpreters, allowing him to unlock far more detailed information (and hopefully avoid any pit falls that might come with miscommunication).

Throughout the winter, Cartier waited impatiently for his chance to return. No, he would never find a middle passage to the Orient. But Cartier truly would discover an aquatic highway of tremendous economic value, one that would do much to determine the course of Canadian history for the next two centuries.