Art and Culture

Paul Was Dead Right

Reappraising one of British journalism’s most notorious pieces of cultural criticism.

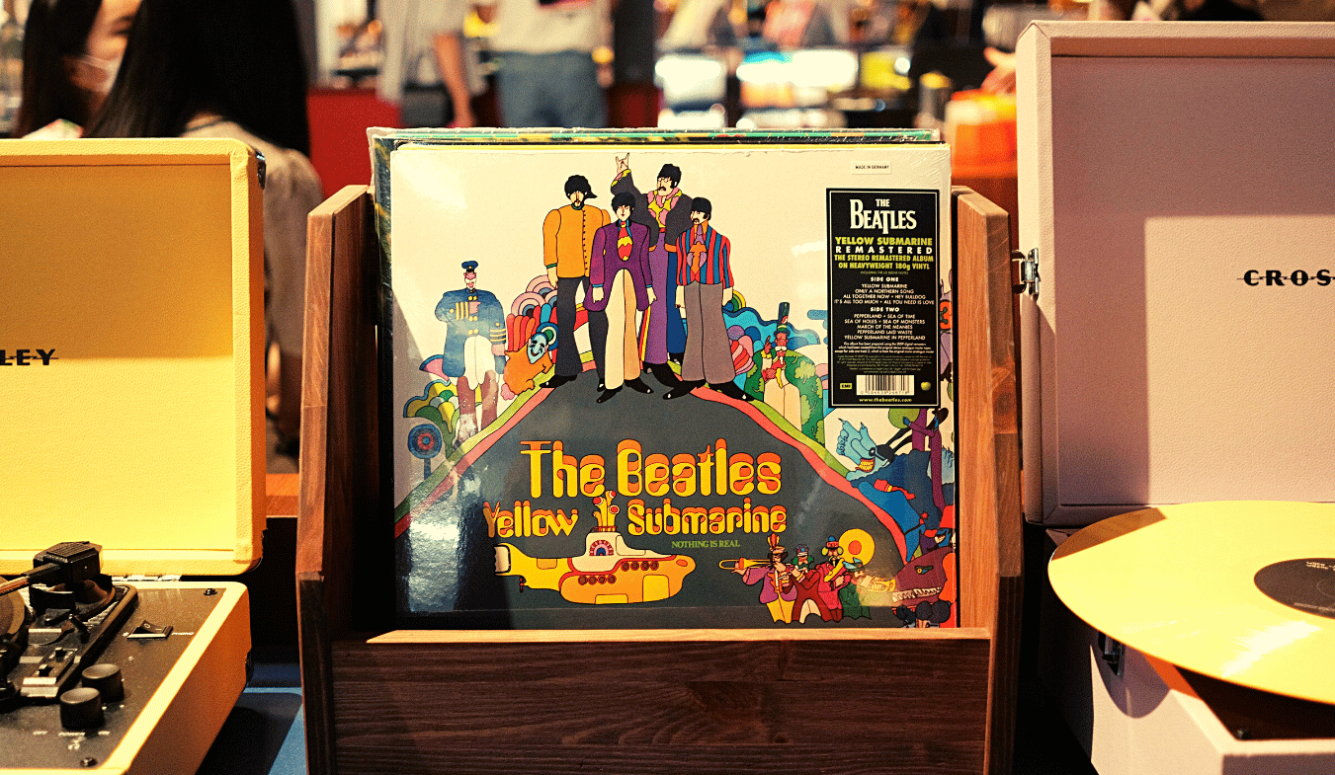

Since their emergence as one of the greatest show-business successes of the 20th century, countless words have been expended on the Beatles. Among all the biography, musicology, and hagiography hailing the eternal genius of the Fab Four, there are a few exceptions, mostly from early in the band’s career, that today read as hopelessly obtuse: “Groups of guitars are on their way out,” predicted the disastrous 1962 rejection by Decca Records’ Dick Rowe; “Their lyrics (punctuated by nutty shouts of ‘yeah, yeah, yeah!’) are a catastrophe, a preposterous farrago of Valentine-card romantic sentiments,” read Newsweek’s summary of the British invaders in 1964; “That’s as bad as listening to the Beatles without earmuffs,” quipped Sean Connery’s James Bond the same year in Goldfinger. But one of the most notorious putdowns may also have been the most prescient—British commentator Paul Johnson’s New Statesman article of February 28th, 1964, “The Menace of Beatlism.”

Published just as John, Paul, George, and Ringo were accelerating into the stratosphere of permanent fame and influence following their initial appearances on the Ed Sullivan show in the United States, Johnson’s essay can now be found on the New Statesman’s website, introduced as “the most complained-about piece in the Statesman’s history.” He called the Beatles an “apotheosis of inanity,” “a mass-produced mental opiate,” and memorably described the teenaged studio audience on a music-oriented television show thusly:

Both TV channels now run weekly programmes in which popular records are played to teenagers and judged. While the music is performed, the cameras linger savagely over the faces of the audience. What a bottomless chasm of vacuity they reveal! The huge faces, bloated with cheap confectionery and smeared with chain-store makeup, the open, sagging mouths … the shoddy, stereotyped, “with it” clothes: here, apparently, is a collective portrait of a generation enslaved by a commercial machine. … How pathetic and listless they seemed: young girls, hardly more than sixteen, dressed as adults and already lined up as fodder for exploitation.

“The Menace of Beatlism” has been widely quoted in musical histories—including The Faber Book of Pop, June Skinner Sawyers’s Read the Beatles, and my own Out of Our Heads—usually as an embarrassing instance of reactionary tone-deafness. After 1964, the Beatles released many more hit records and several classic albums, and left an immeasurable cultural impact; the two surviving members are knighted and a majority of the planet’s inhabitants today can probably recognize their image and at least a few of their melodies. Rolling Stone critic Paul Evans declared in 1992 that “not liking them is as perverse as not liking the sun.” But Johnson, who died last month at the age of 94, may nevertheless have been on to something. He badly misheard the Beatles, but his perception of Beatlism and all it signified was acute.

Johnson’s 1964 essay, in fact, did not comment much on the Beatles’ music or the individual characters of the four musicians. He was more bothered by the cult of novelty and celebrity that was then being exploited by adult politicians and their handlers: a national election loomed that year, and various British candidates were striving to attach themselves to the Beatles’ immense appeal among the young. “The Beatles phenomenon,” he wrote, “… illustrates one of my favorite maxims: that if something becomes big enough and popular enough—and especially commercially profitable enough—solemn men will not be lacking to invest it with virtues.” The problem was not so much the Beatles themselves, but the way the civilization that generated them was becoming so consumed by money, marketing, and a frantic identification with contemporary styles that it risked forgetting the better, deeper parts of its own heritage, as “elders in responsible positions … seek to elevate the worst things in our society to the best”:

Bewildered by a rapidly changing society, excessively fearful of becoming out of date, our leaders are increasingly turning to young people as guides and mentors. … If youth likes jazz, then it must be good, and clever men must rationalize this preference in intellectually respectable language. Indeed, the supreme crime, in politics and culture alike, is not to be “with it” … What were we doing at 16? I remember reading the whole of Shakespeare and Marlowe, writing poems and plays and stories. At 16, I and my friends heard our first performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. I can remember the excitement even today. We would not have wasted 30 seconds of our precious time on the Beatles and their ilk.

Of course, there was nothing new in 1964 about bemoaning mass taste. Leftist critics had long viewed pop culture as a capitalist ploy to distract and pacify the proletariat with bread and circuses proffered by television networks, movie studios, and record companies, while a long line of conservatives interpreted the same product as an egalitarian conspiracy meant to bring intellectual and moral standards down to those of the rabble. Over the course of his life, Johnson may have encompassed both categories: at the time he penned “The Menace of Beatlism,” he was a supporter of Britain’s Labour Party, but he later became an admirer of Margaret Thatcher (his Guardian obituary noted “few rightward shifts of allegiance more dramatic” than his). He went on to establish extensive credentials as a conservative writer and historian and authored sternly judgmental histories including Enemies of Society (1977) and Modern Times (1985).

Before him, American critic Dwight Macdonald had sniffed, in his 1960 book Masscult and Midcult, that “the separation of Folk Art and High Culture in fairly watertight compartments corresponded to the sharp line once drawn between the common people and the aristocracy. The blurring of this line, however desirable politically, has had unfortunate results culturally.” And in 1987’s bestselling The Closing of the American Mind, Allan Bloom echoed Johnson’s anti-Beatles stance with a comparable take on the leader of the Fabs’ friends and rivals, the Rolling Stones. Mick Jagger, Bloom opined, was a “shrewd, middle-class boy, [who] played the possessed lower-class demon and teen-aged satyr up until he was forty, with one eye on the mobs of children of both sexes whom he stimulated to a sensual frenzy and the other eye winking at the unerotic, commercially motivated adults who handled the money.” It’s only rock ’n’ roll, but he didn’t much like it.

The alarms of Macdonald, Bloom, and Johnson certainly come across now as egregiously snobbish and not a little bigoted (“The Menace of Beatlism” disdained jazz as “the monotonous braying of savage instruments”). Many works that originated as disposable culture scorned by intellectual elites—the songs of Irving Berlin, the films of Charlie Chaplin, the fiction of H.P. Lovecraft, the music of Louis Armstrong, Elvis Presley, and, in time, the Beatles and the Rolling Stones—have become certified classics credited with enriching the world’s imagination, aside from the sheer pleasure they delivered to billions of ordinary viewers, readers, and listeners. Indeed, such figures now share a canon with the Shakespeare, Marlowe, and Beethoven revered by the young Paul Johnson. Yet the warning that a too-close attendance to publicity and fashion might divert us from more meaningful measures of truth and beauty remains valid. And the suspicion that celebrated performers’ constituencies might be co-opted by others for opportunistic ends was affirmed by no less an authority than one of the very performers Johnson warned of.

“The same bastards are in control, the same people are runnin’ everything, it’s exactly the same. They hyped the kids and the generation,” John Lennon told Rolling Stone in 1971. “Everybody wants to keep on the bandwagon. … Who was going to knock us when there’s a million pounds to be made?” That same mutual exploitation Lennon experienced firsthand—between ephemeral art and ruthless industry, between momentary attention and lasting power, between faddish popularity and genuine democracy—can be witnessed in the blaring of hit songs at election rallies, and in long meditations published on the “meaning” of a hit movie or TV show. It can be witnessed in the regular cycling of stand-up comedy to news and back; in the angry public debates about the casting of films or the private lives of famous actors; in the endless pursuit of high ratings and viral posts as self-evident goods. It can be witnessed, too, in the elevation of an oafish reality-TV star to high office and the deterioration of learning and politics into inflammatory exchanges over social media platforms owned by billionaires.

In 2023, we are virtually immersed in torrents of electronic entertainment, carried around in the devices to which we’re umbilically tied, and which have flooded into every other sphere of activity, including law, education, and governance—and solemn men (and women) are not lacking who rush to invest it all with virtues, deservedly or not. The Beatles wrote and recorded a lot of wonderful songs, no doubt, and the quartet’s historic rise from scuffling bar band to global icons is the stuff of legend. But our ongoing descent into a bottomless chasm of vacuity, enslaved by commercial machines, may be the historic legacies of the Beatlism whose impending menace the late, lonely Paul Johnson apprehended almost 60 years ago.