Education

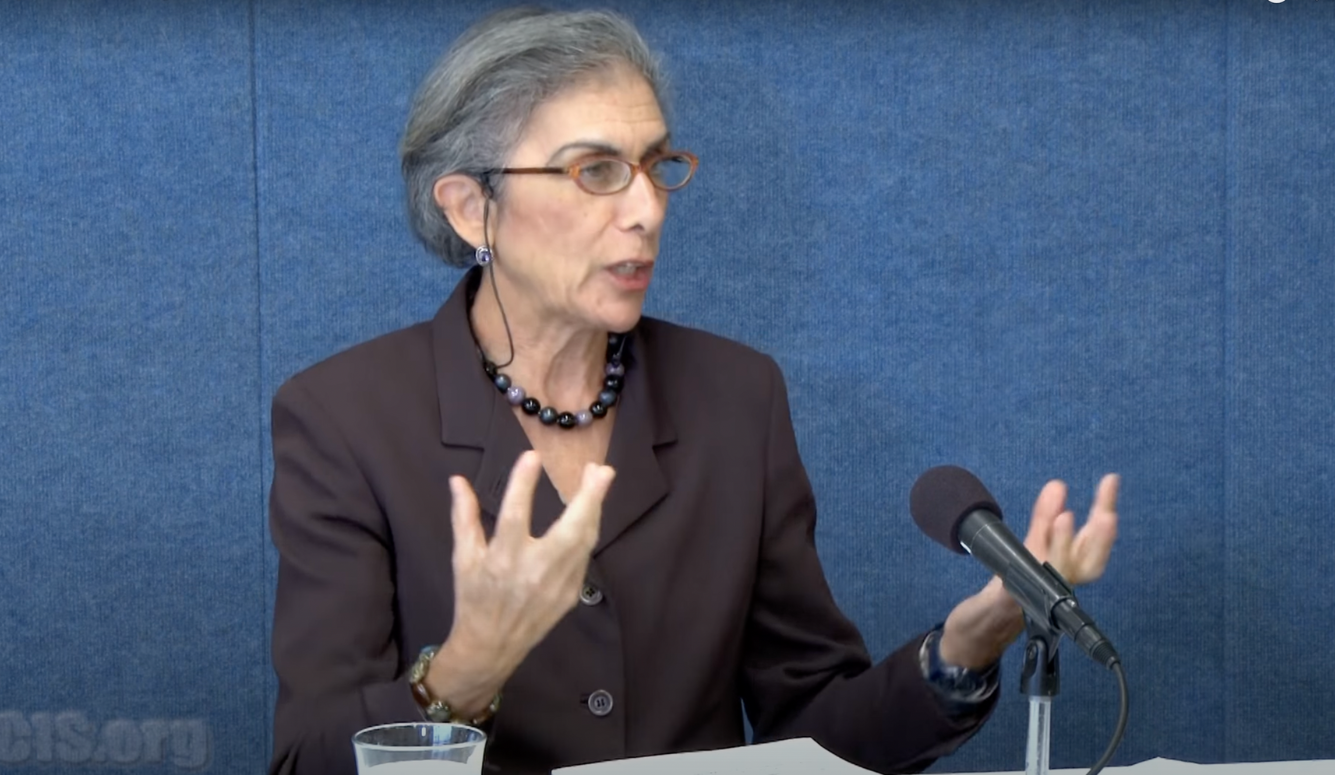

Amy Wax and Academic Freedom

The investigation into the polarizing law professor violates the most basic tenets of academic freedom.

Last summer, Theodore Ruger, Dean of the University of Pennsylvania’s Carey Law School, sent a letter to the chair of Penn’s Faculty Senate requesting a “full review” of the conduct of tenured law professor Amy Wax, and recommending the Senate “impose a major sanction against her.” This was the culmination of a long, five-year struggle with Wax, who has found herself at the center of one firestorm after another. Until then, Ruger had resisted taking this dramatic step, preferring instead to limit Wax’s responsibilities and her contact with students. But his patience with the polarizing professor appeared to have finally run out.

Wax responded by filing a 43 page grievance complaint which attacked the sweeping nature of Ruger’s claims and the disciplinary process itself. In her complaint, Wax raises legitimate questions about how Penn’s Faculty Senate is handling the process of deciding what—if any—sanctions she might face. The heart of her argument correctly maintains that “the allegations in the charges do not concern behavior or actions but only expression.”

Nevertheless, to many inside and outside the Penn community, Wax’s expression is self-evidently beyond the pale and disciplinary action is long overdue. Her public and private comments, they argue, have become increasingly inflammatory (at least in the sense that they have inflamed outrage, regardless of her intent) and have led, as Ruger notes, to a number of students explicitly avoiding her evaluative supervision. Penn’s student newspaper, the Daily Pennsylvanian, reports that enrollment in Wax’s courses is in “sharp decline.”

But the ability to offer sought-after courses is not the root of the problem. The charges against Wax are wholly premised on the claim that her ideas and speech are causing harm to the school’s students. This illiberal view, however popular, is not compatible with the basic tenets of academic freedom. It echoes the sentiments expressed by George Will in 1978 in response to the infamous Nazi march in Skokie, Illinois. “There are political purposes for protecting free speech,” Will argued, “and some speech is incompatible with those purposes.” A free speech liberal at the time (like those who staffed the ACLU) would have pointed out how dangerously precarious that view is as political winds and concerns shift.

One of the central complaints in Ruger’s letter is that Wax’s speech in the classroom and in public “leads reasonable students to conclude that they will be judged and evaluated based on their race, ethnicity, gender, national status, or sexual orientation rather than their academic performance and ‘true merit.’” He quotes students who believe “it is ‘impossible to fathom’ that Wax will ‘treat non-conservative, not-white students fairly.’”

This seems concerning. But plenty of faculty around the country, and at Penn, express strong views about the merits of the demographic groups into which their students fall. In 2021, Anthea Butler, Chair of the Department of Religious Studies at Penn, published a book titled White Evangelical Racism which is mentioned in her bio on the department’s website. The book’s thesis is that “Racism is a feature, not a bug, of American evangelicalism,” and Butler concludes her historical review by speaking directly to her subjects: “Evangelicals,” she writes, “you have a problem. That problem is racism.” This racism, she argues, “is hurting others. Your racism is actively engaging in killing bodies and souls.”

Surely, we can see how an evangelical student might find it “impossible to fathom” that Butler would treat a conservative, white, evangelical student fairly. Wax’s detractors would likely argue that this is an asymmetric comparison, but that position is itself a political one. Forceful and sweeping statements and criticisms about groups of people are de rigueur in a wide variety of disciplines today.

This is not the only case of a controversial professor facing serious sanctions as a result of the things they have said. In May of 2022, Princeton fired classics professor Joshua Katz. Two years earlier, Katz had published an essay in these pages critical of an open letter, signed by nearly 500 Princeton faculty, staff, and students, which called for sweeping changes to address “anti-black racism [that] has a visible bearing upon Princeton’s campus.” Princeton insisted that Katz’s firing was justified by old allegations of a relationship he’d had with a student. However, it subsequently became clear that this was not the primary reason for his dismissal.

The Wax affair represents an even more clear-cut case of academic freedom. As of this writing, no unrelated policy violation has been alleged that might offer a pretext for her firing. If she is sanctioned, it will be as a result of the views she has expressed and nothing else. This puts those of us who believe in free speech in the difficult position of defending someone whose views we may not like (much like the ACLU). But, that the content of Wax’s comments is difficult to defend is exactly why they need to be defended from university sanction by believers in academic liberty. The bounds of academic freedom have always been contentious by definition, and shrinking the sphere of acceptable speech will only serve to position other current and future scholars closer to the edge than they previously thought they were.

Wax’s trajectory is remarkably similar to that of another scholar whose case contributed to the adoption of strong protections for academic freedom and the creation of the tenure system. Edward Alsworth Ross was an economics professor at Stanford University in the late 19th century until Jane Stanford herself forced the university’s first president, David Starr Jordan, to fire him. At issue was Ross’s role in the Free Silver Movement, his outspoken partisan political views, and his increasingly strident and inflammatory anti-immigrant rhetoric. Jane Stanford’s efforts to get Ross fired began after Ross declared his support for the Democratic candidate William Jennings Bryan in the 1896 presidential election. She was, like her late husband, a staunch Republican and took issue with Ross’s public declaration.

It wasn’t until 1900 that Stanford finally exercised her power as the sole trustee of the University and forbade Jordan from renewing Ross’s annual contract. Ross had become involved with the early American labor movement and was firmly opposed to Japanese and Chinese immigration. That immigration had enabled the Stanford family and other railroad barons of the age to amass huge fortunes on the backs of cheap and exploited immigrant labor. In a speech that would lead to what would come to be called “The Ross Affair,” Ross was reported to have said “and should the worst come to the worst it would be better for us if we were to turn our guns upon every vessel bringing Japanese to our shores rather than to permit them to our land.”

Jane Stanford, like Ruger, had had enough. She wrote to Jordan that Ross had gone out of his way “to associate himself with the political demagogues of this city, exciting their evil passions, drawing distinctions between man and man” and that this “literally plays into the hands of the lowest and vilest elements of socialism.” Both of these sentiments—that Ross could be dismissed because his views were evil and that this evil allegedly benefitted socialism—should give us pause.

“The Ross Affair” and other high-profile incidents in the early 20th century led to the formation of the American Association of University Professors. Their seminal 1915 and 1940 statements form the backbone of the system of tenure and academic freedom we know today. Both statements are particularly clear on one point: sanctions and limitations on the views of scholars open the door to speech suppression that the original proponents almost certainly never intended. If Wax is sanctioned, this new draconian standard may in time be used to punish those expressing views with which her enemies agree.

Ruger’s complaint also states that “on multiple occasions, Wax has violated the confidential relationship with her students by publicly discussing their performance.” Wax has never spoken publicly about a specific student’s performance, she has commented on the average performance of groups of students. That is hardly unprecedented, and if this standard is to be consistently applied across the university, other investigations into other faculty members will be necessary. In January 2022, Nina Strohminger, Assistant Professor of Legal Studies & Business Ethics at The Wharton School, tweeted:

I asked Wharton students what they thought the average American worker makes per year and 25% of them thought it was over six figures. One of them thought it was $800k. Really not sure what to make of this (The real number is $45k)

— Nina Strohminger (@NinaStrohminger) January 20, 2022

That tweet was retweeted over 34,000 times, quote-tweeted over 10,000 times, and liked over 200,000 times. It prompted articles in the Washington Post, Forbes, Fortune, Newsweek, and Penn’s hometown paper the Philadelphia Inquirer. Six days later, the Daily Pennsylvanian ran a story about how the tweet led to a “national debate on income inequality.” Absent from this coverage was any discussion of whether or not Strohminger had “violated the confidential relationship with her students.”

To make Strohminger the subject of a disciplinary proceeding for that tweet would be absurd. We want scholars to make challenging and provocative statements that force us to grapple with difficult questions. The only functional difference between Strohminger’s tweet and the incidents involving Wax is that Wax was discussing the underachievement of black students rather than her students’ ignorance of economics. On the point of principle at issue, this is a distinction without a difference.

Penn’s own history bears on these difficult questions of what is, and is not, within the protected bounds of academic freedom. In the summer of 1965, Penn undergraduate Robin Maisel discovered a secret research lab in an off-campus building while he was working at the university’s bookstore. It would later emerge that the lab was part of a secret project researching chemical and biological weapons on Penn’s campus. Faculty and students were dismayed to discover that Penn was involved in researching weapons they saw as inherently immoral and supportive of the Vietnam War. Protests and teach-ins were held, and the Faculty Senate and university administration spent considerable time attempting to balance the protection of academic freedom and legitimate concerns about its excesses. The Faculty Senate’s then-chairman Julius Wishner concluded that, “while the topic of research should be left to the individual scholar, results had to be reported in literature open to the entire scholarly community.”

The Wax case does not involve secret research, but it does confront what does and does not fall within the acceptable realm of ethical standards set out by the university community. Wishner’s proposed understanding should be our guide. The ethical question at issue cannot be judged on the content of research or speech, but rather whether it is openly presented and subject to wider debate. Wax has been extremely frank about her views. In fact, her frankness is a big part of the problem. However objectionable Wax’s speech may be, it has been laid out for scrutiny and subject to critical responses for half a decade. Removing Wax from her position will not make her ideas disappear, it will just make them less visible. Respecting her rights under the system of tenure allows those of us who oppose her views to offer a rejoinder.

The third charge of note against Wax is that she invited white nationalist Jared Taylor to speak at a mandatory lecture for one of her courses. Students in the school—though Ruger makes no reference to students in the class itself—were deeply uncomfortable with this decision. That was, presumably, the point. The course in question was on Conservative Political and Legal Thought, and Wax has said that she invited Taylor to “talk to [her] students about the far-Right and the far-Right movement.” She maintains that if she is to teach a course on conservative thought, her students must read and encounter a variety of conservatives. She calls Ruger’s inclusion of the Taylor invitation in his letter “educational malpractice of the first order,” adding later that “this is actually my little capsule version of what is going on in academia today.”

Since the beginning of this slow-burning controversy, Wax has tested the limits of what is generally considered acceptable within academe. The 2017 op-ed she co-authored with Larry Alexander for the Philadelphia Inquirer and the 2018 piece she subsequently wrote for the Wall Street Journal in response to her critics explicitly argued that certain verboten ideas should be brought back into the sphere of academic debate. She and Alexander critiqued the persistent success of the 1960s’ counterculture, “particularly among the chattering classes—academics, writers, artists, actors, and journalists—who relished liberation from conventional constraints and turned condemning America and reviewing its crimes into a class marker of virtue and sophistication.”

Wax’s follow-up piece was titled “What Can’t Be Debated on Campus,” and she opened by saying, “There is a lot of abstract talk these days on American college campuses about free speech and the values of free inquiry. … It is only when people are confronted with speech they don’t like that we see whether these abstractions are real to them.” It should not be any surprise that she invited someone like Jared Taylor, whose presence on campus was guaranteed to cause uproar, to demonstrate her commitment to the actual practice of free inquiry.

Provocative acts that elicit visceral responses can be an effective form of pedagogy. In 1989, Carolyn Marvin, now Professor Emeritus at the Annenberg School for Communication, burned an American flag during her History and Theory of Freedom of Expression class. This was the same year the Supreme Court ruled that flag burning was protected speech under the First Amendment. As a result, proposals were floated to outlaw flag-burning by constitutional amendment. Polling conducted that year by ABC News and the Washington Post found that 74 percent of Americans thought it was “very important” to “make the destruction or burning of the American flag as a form of political protest against the law.” A Times Mirror poll found that 65 percent of Americans favored a constitutional amendment making it illegal.

Marvin’s lesson achieved its aim: to “prompt class discussion on free speech.” Reaction beyond her classroom, however, was predictably mixed, with some both on and off campus taking great offense. The following year, “the Pennsylvania House of Representatives voted 189-4 to condemn Marvin for an ‘outrageous act of desecration.’” But Penn President Sheldon Hackney defended her on the grounds that her actions fell within the parameters of academic freedom.

Many will object that burning a flag and inviting a white nationalist to speak to a class are not equivalent—but is the difference material or simply ideological? Both actions provoked offence, and the fact that those offended by the flag-burning were conservatives on a left-leaning, Ivy League campus does not invalidate the sincerity of that response. As Ruger’s letter makes clear, real and serious offense was taken to Wax’s actions and that offense is grounds for sanctions. But, to act differently in the Wax case than in the Marvin case is to decide that one group is worthier of protection than another.

News of Ruger’s letter broke in the midst of another major story in contemporary conflicts around academic freedom. Nikole Hannah-Jones, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and Knight Professor in Race and Journalism at Howard University, announced that she had reached a settlement with the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill following the 2021 debacle surrounding her appointment at UNC.

What’s striking about the timing of these two announcements is that, in Hannah-Jones’s case, UNC violated the spirit of academic freedom. The protections of academic freedom by an institution only actually extend to faculty who work there, not necessarily to faculty under consideration for a position. Wax’s case violates the letter of academic freedom. Hannah-Jones was lauded as a courageous defender standing up to the political powers interfering in her appointment and freedom as a scholar. Wax is widely condemned as an example of the excesses of the system. However, if we strip away the politics and ideology of the two cases, it’s clear that these controversies are fundamentally debates about the same question: Can scholars speak freely without fear of institutional retribution?

I regret that I feel compelled to defend Amy Wax. I do not particularly like her politics or her view of the world. My time, and the time of every other person who has sought intellectual enrichment in academe, would be better spent discussing her ideas. Yet the trend on Penn’s campus is not encouraging.

As one committee in the Faculty Senate considers Wax’s case, another seems to be looking towards making it easier to dismiss faculty with unpopular positions. Last month, it was reported that the Committee on Faculty Development, Diversity, and Equity is poised to deliver a report on “the needs of the Penn community who feel ‘victimized’ by faculty, especially in relation to academic freedom.” Last year, the same committee recommended that the Faculty Senate re-examine current policy “related to balancing academic freedom and tenure protections with the need for faculty sanctions (including possible tenure removal) for faculty misbehaviors with a particular focus on bringing more transparency to this process and considering the needs of those who have been victimized by these misbehaviors.”

Amy Wax is sometimes referred to as a white supremacist. If such an accusation is to be considered sufficient grounds for serious sanction by the university, the implications are troubling. So expansive has the definition of “white supremacy” become that even left-leaning professors may soon find themselves under attack for falling foul of it. Alternatively, an illiberal counter-movement on the Right may sanction them for teaching “Critical Race Theory.” After all, in academic freedom (as George Will would hopefully now acknowledge), Newton’s third law applies: every action has an equal and opposite reaction.

Choosing which groups are to be protected from faculty speech is fundamentally anathema to the ideal of academic freedom because that choice is never made in isolation. Those currently in a position to censure and censor others will not be in that position forever and may one day find themselves on the receiving end of the punishments they are now meting out to their ideological opponents. Those who abhor Wax’s views should have the foresight to understand that it is in their interests to defend her right to express them. Freedom for a professor like Amy Wax ensures freedom for everyone.