Politics

Heidegger’s Downfall

Richard Wolin’s reappraisal of Martin Heidegger offers both original contributions and a synthesis of critical scholarship. The result is a timely work of enduring importance.

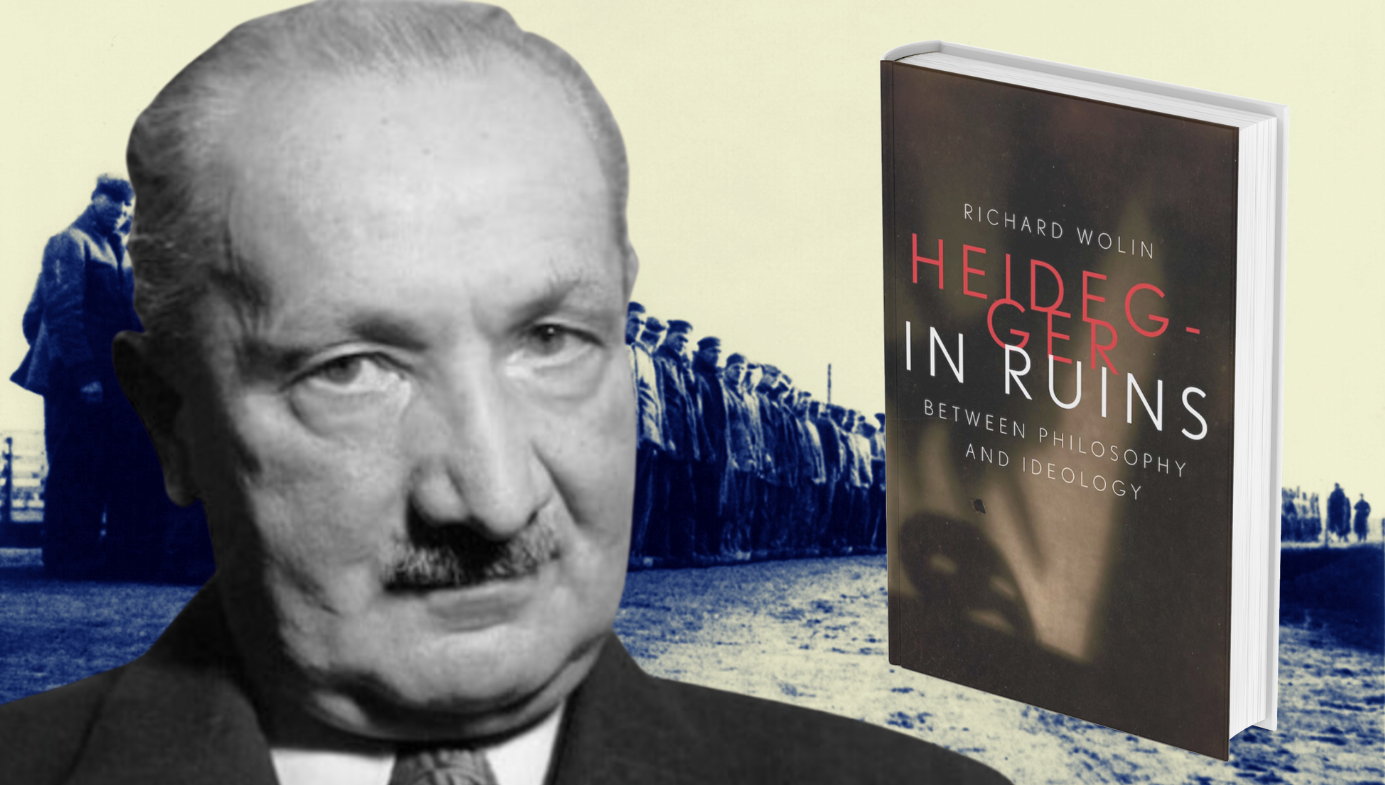

A review of Heidegger in Ruins: Between Philosophy and Ideology by Richard Wolin, 473 pages (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2022)

On April 21st, 1933, the German philosopher Martin Heidegger, then famous as the author of the 1927 philosophical treatise Being and Time, gave one of the most famous speeches delivered by any scholar living in the dictatorships of the 20th century. It was titled, “The Self-Assertion of the German University,” and it called upon students at the University of Freiburg to abandon objectivity and academic freedom and instead join the “spiritual mission which impresses onto the fate of the German Volk [people] the stamp of history” while the “moribund pseudocivilization” of the West “collapses into itself.”

By the time Heidegger delivered that speech, the Nazi regime had already declared a national emergency and suspended civil liberties following the Reichstag Fire of February 28th. The regime had violently destroyed the Communist and Social Democratic Parties, thereby clearing a path to dictatorship, and it had introduced national legislation calling for the expulsion of all Jews from the civil service. The antisemitic clauses of the Nazi Party were now government policy, and purges of Jewish professors were underway in the universities, including at Freiburg, where Heidegger had just been elected rector. Over the summer and into the fall, he openly declared his support and admiration for Hitler and the new regime and called upon all to vote for the Nazis in elections.

For many of his contemporaries, Heidegger’s texts of spring to fall 1933 offered sufficient proof that he had placed the prestige of the academy in the service of evil—a paradigmatic example of the betrayal of the intellectuals who abandoned liberal democracy for the supposed benefits of totalitarianism. But a spectrum of theorists across the Left and Right have stubbornly refused to accept that the reputation Heidegger acquired in 1927 as a serious philosopher was dented by his support for Nazism, which they maintain was merely an irrelevant (albeit embarrassing) deviation.

In six previous books since 1990, American historian Richard Wolin has sought to take Heidegger seriously as a philosopher while also placing him in the context of German intellectual and political history. In his seventh installment in this series, Heidegger in Ruins: Between Philosophy and Ideology, Wolin examines the philosopher’s Black Notebooks. Finally published between 2014 and 2022, in volumes 94 to 102 of his collected works, the Black Notebooks contain essays, lectures, and notes Heidegger wrote between 1931 and 1970.

Wolin’s reassessment of this material is an important work that examines the philosopher of “Being” against the backdrop of the reactionary antidemocratic milieu in which he lived and worked. It emphasizes Heidegger’s intense German nationalism, presents evidence that his support for Nazism was enduring not short-lived, and argues that the intensity of his antisemitism was greater than even his early critics realized.

Heidegger in Ruins draws on the work of a range of historians to present the by-now familiar story of Weimar’s reactionary modernists who attacked democracy and supported dictatorship. But four other elements of the book are new and important, especially in the English language scholarship. First, Heidegger’s mendacity and his corruption of scholarly ethics in connection with the publication of his collected works; second, the persistence and the intensity of his radical antisemitism; third, the apocalyptic, extremist, and eschatological nature of his writings during World War II and the Holocaust; and fourth, the manner in which his discussion of technology contributed to apologia for Nazism in postwar West Germany.

It is now a consensus among historians that Heidegger’s convictions, expressed in his teaching and correspondence throughout the Nazi regime, echoed and deepened the sentiments of his texts from spring to fall in 1933. In 2014, Peter Trawny, an editor of Heidegger’s collected works (Gesamtausgabe), published Heidegger und der Mythos der jüdischen Weltverschwörung (republished in English translation a year later by the University of Chicago Press as Heidegger and the Myth of the Jewish World Conspiracy). This work, along with the publication of the Black Notebooks, made it impossible to ignore the realities of Heidegger’s virulent antisemitism.

In 1998, Wolin published The Heidegger Controversy, an edited collection of Heidegger’s texts supplemented by commentaries from his contemporaries and early critics. Wolin included a translation of Karl Löwith’s essay, “The Political Implications of Heidegger’s Existentialism,” first published in Les Temps Modernes in 1946. Löwith, who knew Heidegger, wrote:

Given the significant attachment of the philosopher to the climate and intellectual habitus of National Socialism, it would be inappropriate to criticize his political decision [to support the Nazi regime] in isolation from the very principles of Heideggerian philosophy itself. It is not Heidegger, who, opting for Hitler, “misunderstood himself”; instead, those who cannot understand why he acted this way have failed to understand him.

Löwith wrote that the famous Heideggerian language of existence (dasein) and resolve, the appeals to discipline and coercion, danger and disruption, reflected “the disastrous intellectual mind-set of the German generation following World War I” (emphasis in Wolin). These were the ideas of the “conservative revolution” aimed at ending the liberal experiment of the Weimar Republic in favor of a presumably more inspiring and fulfilling authoritarian regime.

In The Heidegger Controversy, Wolin also included an exchange of letters between Heidegger and his former student Herbert Marcuse. Marcuse was then working with Franz Neumann in the United States government’s Office of Strategic Services, helping to win the war against the Nazi regime. On August 28th, 1947, Marcuse wrote the following to his former professor:

I—and very many others—have admired you as a philosopher; from you we have learned an infinite amount. But we cannot make the separation between Heidegger the philosopher and Heidegger the man, for it contradicts your own philosophy. A philosopher can be deceived regarding political matters; in which case he will openly acknowledge his error. But he cannot be deceived about a regime that has killed millions of Jews—merely because they were Jews—that made terror into an everyday phenomenon, and that turned everything that pertains to the idea of spirit, freedom, and truth into its bloody opposite. A regime that in every respect imaginable was the deadly caricature of the Western tradition that you yourself so forcefully explicated and justified. And if that regime was not the caricature of that tradition but its actual culmination—in this case too, there could be no deception, for then you would have to indict and disavow this entire tradition.

Despite Marcuse’s own Frankfurt School ambiguity about whether Nazism was a caricature or culmination of the Western tradition, he had no doubt that Heidegger the philosopher could not be separated from the Heidegger who had supported Nazism. In the same work, Wolin also included a 1953 essay by the young Jürgen Habermas, titled, “Martin Heidegger: On the Publication of the Lectures of 1935,” in which Habermas asked:

Can the planned murder of millions of human beings, which we all know about today, be also made understandable in terms of the history of Being as a fateful going astray? Is this murder not the actual crime of those who, with full accountability, committed it? Have we not had eight years since then to take the risk of confronting what was, what we were? Is it not the foremost duty of thoughtful people to clarify the accountable deeds of the past and keep the knowledge of them awake? Instead, the mass of the population practices continued rehabilitation, and in the vanguard are the responsible ones from then and now. Instead, Heidegger publishes his words, in the meantime eighteen years old, about the greatness and inner truth of National Socialism, words that have become too old and that certainly do not belong to those whose understanding still awaits us. It appears time to think with Heidegger against Heidegger.

In so doing, Habermas raised the issue of Heidegger’s refusal, after 1945, to honestly reckon with the realities of Nazi Germany’s crimes, including the Holocaust, and his own role in lending support to the regime.

In 1958, the West German historian Christian Graf von Krockow published Die Entscheidung: Eine Untersuchung über Ernst Jünger, Carl Schmitt, and Martin Heidegger (“The Decision: An Examination of Ernst Jünger, Carl Schmitt, and Martin Heidegger”). Krockow accurately described these three men as leading ideologues of Weimar’s conservative revolution. In 1964, in Die Jargon der Eigentlichkeit (“The Jargon of Authenticity”), Theodor Adorno, then a professor of sociology and philosophy in the University of Frankfurt/Main, argued that the language of Heidegger’s Being and Time also contributed to the postwar avoidance of the realities of Nazism.

And in 1975, the West German philosopher, Winfried Franzen argued that that there was a close connection between the existential ontology of Heidegger’s Sein und Zeit and his political engagement for Nazism. Indeed, restoring Heidegger to his own time and place was a leitmotif of efforts by West German liberals to reckon honestly with the Nazi past during the postwar decades.

It was with their work in mind that I included Heidegger in my 1984 work Reactionary Modernism: Technology, Culture and Politics in Weimar and the Third Reich. I wrote that “when Heidegger was able to connect the destiny of the Germans with that of ‘being’ in general, his path to Hitlerism was cleared. … National Socialism [for Heidegger] represented the revolt of the German Volk to regain its threatened being.” In this way, Nazism and Hitler would save “being” from the ravages of Western progress, and German dasein from a “sharp pincer movement between America and Russia.” For Heidegger, the “inner truth and greatness” of Nazism also illuminated “the confrontation of planetary technology with modern man.”

In 1987, Victor Farias, a Chilean historian then teaching in Freiburg, published Heidegger und der Nationalsozialismus, to which Habermas contributed the foreword. Farias demonstrated that Heidegger’s support of the Nazi regime persisted up to its end. In 1992, Hugo Ott, professor of Economics and Social History at Freiburg University, published Martin Heidegger: Unterwegs zu seiner Biographie (published in English translation by Basic Books as Martin Heidegger: A Political Life in 1993).

Ott’s work explored how Heidegger’s support for Nazism affected Freiburg University. The material on postwar denazification proceedings and faculty debates about Heidegger make for particularly interesting reading. Among those supporting his complete separation from the university was Franz Böhm, a professor of economics who later became a member of the West German parliament, and who played a central role in supporting West Germany’s policy of restitution toward the Jewish survivors of the Holocaust. On October 9th, 1945, Böhm wrote to the Freiburg University rector’s office to protest the mild initial judgement about Heidegger in the university denazification commission report:

It makes me very bitter to think that one of the principal intellectual architects of the political betrayal of Germany’s universities, a man who at a critical moment in time, from a position of prominence as the rector of a leading German borderland university and a philosopher of international standing, became the vociferous spokesman of an intolerant fanaticism, charted the wrong political course and preached a catalogue of pernicious heresies, heresies which to this day he never repudiated—that a man such as this should merely have been subjected to the stricture of “diponibilite” [availability], and clearly feels no need at all to answer for the consequences of his actions.

Böhm was clearly unimpressed by Heidegger’s philosophical contributions. The Freiburg faculty, influenced also by Karl Jaspers’s recommendations, refused Heidegger permission to teach, but did grant him emeritus status. West German liberals did their best to focus on the realities of Heidegger’s ideas and politics, but Heidegger nonetheless found an audience in France among the existentialist Left (in the person of Jean-Paul Sartre) and the advocates of deconstruction (Georges Bataille and Maurice Blanchot). These thinkers, in turn, influenced American discussions of Heidegger. All decided that Heidegger’s philosophical works could and should be assessed independently of his Nazism. (Wolin examined those issues in his 2004 book, The Seduction of Reason: The Intellectual Romance with Fascism from Nietzsche to Postmodernism.)

However, as references to Heidegger were proliferating in American departments of English and History, the West German, French, and American scholarship on Heidegger’s historical and philosophical connections to Nazism was expanding significantly. This included Tom Rockmore’s On Heidegger's Nazism and Philosophy, Johannes Fritsche’s Historical Destiny and National Socialism in Heidegger’s ‘Being and Time’ (1999), Charles Bambach’s Heidegger’s Roots: Nietzsche, National Socialism, and the Greeks (2003), Daniel Morat’s Von der Tat zur Gelassenheit: Konservatives Denken bei Martin Heidegger, Ernst Jünger, und Friedrich Georg Jünger (2003), Emmanuel Faye’s Heidegger: The Introduction of Nazism into Philosophy (2011), and Florian Grosser’s Revolution Denken: Heidegger und das Politische 1919 bis 1969 (2014).

In Heidegger in Ruins, Wolin writes that all this scholarship has now “convincingly shown that Heidegger’s existential ontology is shot through with the idiolect of the conservative revolution.” Close textual readings and archival research have lent support to the views expressed in the postwar months and years by Adorno, Böhm, Marcuse, Jaspers, Löwith, and Habermas. The publication of the Black Notebooks only reinforced what Heidegger’s contemporaries and two generations of historians had already concluded.

As Wolin puts it, “the Black Notebooks attest prodigiously to the timeliness of Heidegger’s work, to the crucial dynamic between metaphysics and Zeitgeschichte. As such, they are saturated with historicity, in ways that existing secondary literature has yet to fully explore.” In fact, the secondary literature produced by historians had long documented and interpreted the links between metaphysics and contemporary history in Heidegger’s work, but that work had only modest impact on scholars in departments of literature and philosophy, especially in the decades when postmodernism became fashionable.

In the opening chapter of Heidegger in Ruins, titled “The Heidegger Hoax,” Wolin examines Heidegger’s mendacity, and the violation of scholarly norms by those publishing his collected works (Gesamtausgabe). In those now 102 volumes, “the scope and degree of his [Heidegger’s] National Socialist allegiances have been consistently downplayed and misconstrued.” That fact, he adds, has been “an open secret” among Heidegger scholars but rarely publicly discussed. “For decades,” his published works were “systematically manipulated by a coterie of well-disposed literary executors,” including family members and “interested parties possessing limited professional competence” who displayed “blatant disregard for conventional scholarly standards.”

This “opened the door to a series of highly compromising editorial falsifications and distortions” and the publication of “politically sanitized versions of Heidegger’s texts … in which evidence of Heidegger’s pro-Nazi and anti-Semitic convictions was consistently masked and expunged. … Numerous passages that attested to the magnitude and depth of his ideological zealotry during the Nazi years were systematically elided” (emphasis in original). These deletions included Heidegger’s 1936 praise of Hitler and Mussolini for introducing a “countermovement to nihilism,” intended as praise for their invocation of the Nietzschean will to power.

Wolin notes that Heidegger published revised versions of texts as if they were the originals. The 1953 edition of An Introduction to Metaphysics, based on a lecture course in 1935, replaced “the inner truth and greatness” of “National Socialism” with reference to “this movement” arrayed against the “confrontation of planetary technology and modern man.” Heidegger’s postwar claims to have repudiated National Socialism were really nothing more than criticisms of his fellow Nazi-supporting academic rivals. Entire pages of Heidegger’s lectures on Nietzsche, published in 1961, were “excised or rewritten” but the edits were never publicly acknowledged.

Many of the expunged passages have now been restored to Heidegger’s 102-volume Gesamtausgabe. However, Wolin reminds us that, in 2014, Trawny revealed that, while working on Heidegger’s lectures of 1939 in the 1990s, he agreed to excise Heidegger’s assertion that “it would be worthwhile inquiring into world Jewry’s predisposition toward planetary criminality.” Wolin notes that this contradicts the misleading claim, “frequently advanced by Heidegger’s diehard defenders, that Heidegger rejected race thinking as a matter of principle.”

Heidegger made that statement shortly after Hitler’s infamous “prophecy” speech of January 30th, 1939, in which he declared that if “international Jewish financiers” were to start another world war, “the result will not be the Bolshevization of the earth, and the victory of Jewry, but the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe.” In Heidegger in Ruins, Wolin plausibly suggests that, “Heidegger’s comments seem to represent a profession of solidarity with Hitler’s views.” This is almost certainly why Heidegger sought to pass off revised texts as originals during the early 1950s in an attempt to suppress evidence of his explicit support for Nazi doctrine.

In 2015, the editorial scandal surrounding the revision of Heidegger’s collected works finally became public. His German publisher, Klostermann, acknowledged “numerous inquiries as to why Martin Heidegger’s anti-Jewish enmity hadn’t surfaced in Gesamtausgabe volumes that had been previously published. … Recent discoveries have raised the concern that a search for further inaccuracies in the Gesamtausgabe will arise.” That same year, philosopher Marion Heinz, of the University of Siegen, concluded that, due to deletions and insertions, “we have no reliable basis at our disposal to research and evaluate Heidegger’s philosophy.”

But by then, as Wolin points out, the damage had been done. The problems in the previous volumes of Heidegger’s collected works were also evident in the Black Notebooks. “As a result,” he writes, “for the foreseeable future, generations of students encountering Heidegger’s work for the first time will be exposed to editorially doctored, politically cleansed versions of Heidegger’s thought. These significantly flawed texts have, meretriciously, become the de facto standard editions.” Heidegger’s translators have compounded the problem by offering English versions of German terms, such as Volk or Bodenständigkeit, that obscure their irrationalist and racist implications in German.

Four subsequent chapters of Heidegger in Ruins examine the material in the Black Notebooks. Chapter Two, “Heidegger in Ruins,” details the intensity of the philosopher’s German nationalism, antisemitism, and enthusiasm for Nazism as a force of destruction and redemption. Chapter Three, “Heidegger and Race,” examines the parallels between Heidegger’s philosophical celebration of German “Being” and the Nazi regime’s own racist ideology which vilified Jewish “rootlessness.” Chapter Four, “Arbeit Macht Frei: Heidegger and the German Ideology of Work,” recalls the importance Heidegger placed on Ernst Jünger’s celebration of authoritarianism and explores the philosophical gloss that Heidegger provided to Nazism’s views of work and discipline. Chapter Five, “Earth and Soil: Heidegger and the National Socialist Politics of Space,” examines how Heidegger’s prewar and wartime reflections lent philosophical support to German aggression and expansion during the course of World War II.

The depth of Heidegger’s antisemitism was frankly expressed in his many years of correspondence with his brother Fritz. In 1931, two years before Hitler came to power, Wolin tells us Heidegger wrote the following about Mein Kampf: “No one who is insightful will dispute the fact that, whereas often the rest of us remain lost in the dark, this is a man [Hitler] who is possessed of a sure and remarkable political instinct … what is at stake is the redemption or destruction of Europe and Western Culture.” Until 2016, this document was omitted by those overseeing Heidegger’s collected works and correspondence.

As Heidegger scholars have demonstrated for many years, the philosopher placed the conventional political history of the Nazi regime into a grander narrative of “another Beginning” required to overcome a decline of “Being” since the Greeks. For Heidegger, Germany and the Germans occupied the exceptional status in that effort. The Jews, on the other hand, were “rootless” advocates of liberalism. “World Jewry,” a term used only by antisemites and made more famous by Nazi propaganda, was bereft of the redeeming depths of the Germans. Or, in Heideggerian terms: “The more primordial and original … future decisions and questions become, the more inaccessible they remain for this race [the Jews].” He expressed these sentiments in the Black Notebooks written between 1939 and 1941—that is, during the years in which Hitler and Goebbels were denouncing “World Jewry” as “the Jewish enemy,” and first threatening then carrying out their extermination.

Wolin argues that Heidegger’s 1943 text, “The Beginning of Western Thinking: Heraclitus,” is particularly revealing. Heidegger insisted that “only the Germans—and they alone—can redeem the West and its history. … The planet is in flames. The essence of man is out of joint. Only from the Germans, provided they discover and preserve their Germanness, can world-historical consciousness arrive.” In the years preceding the war, Heidegger praised “National Socialism as a barbaric principle. … Therein lies its essence and its capacity for greatness. … The danger is not [National Socialism] itself, but instead that it will be innocuous via sermons about the True, the Good, and the Beautiful.” Elsewhere he wrote that, “Everything must be exposed to complete and total devastation. In this way alone might one shatter the 2,000-year reign of [Western] metaphysics.” Brutality, callousness, and destruction, he believed, were elements of a Nietzschean will to power that would replace the decadent West and its threatening rationality with a new history.

Heidegger’s fanatical and apocalyptic thinking, Wolin observes, are also evident in the Black Notebooks. He hoped that the Germans would reverse a long decline of Being, but redemption would require catastrophe and cataclysm. As some point between 1931 and 1938 (the specific dates of texts are not in Heidegger in Ruins), Heidegger called Untergang—“downfall” or “decline”—“the essential precondition for historical greatness.” In the notebooks of 1939 to 1941, Heidegger appeared to descend into madness. The “purification of being” (Reinigung des Seins), he wrote, would culminate in “the self-obliteration of the earth and the disappearance of contemporary humanity.” Such a catastrophe was not to be feared but welcomed as an act that would bring about “purification of Being from the thoroughgoing distortions resulting from the predominance of ‘beings.’” During those years, Heidegger emerges as a prophet of apocalyptic destruction who would usher in a new and redeemed world—a “second coming” for sophisticates.

When Heidegger advised, in his 1939 work, Die Geschichte des Seyns (“History of Being”), that “it would be worthwhile inquiring into world Jewry’s predisposition toward planetary criminality,” he was hardly alone. The Nazi regime funded research institutes that hired PhDs to write essays and books along precisely these lines, and professors and doctorates dutifully complied. Heidegger’s suggestion was fully in tune with the spirit of the times in Nazi Germany. Hitler delivered antisemitic rants about a vast international Jewish conspiracy waging war against the Germans, and the pseudo-scholarly works produced by the universities and Nazi-funded “research” institutes claimed to uncover its roots. The accusation of Jewish criminality that Heidegger repeated was central to Hitler’s justification for the Final Solution.

Wolin’s examination of Heidegger’s contributions to the apologia for Nazism in postwar West Germany exposes their importance. As I argued in Reactionary Modernism, the Nazis insisted that they had created what Goebbels called the “steel-like romanticism of the twentieth century.” But Heidegger believed that the Jews and their rootless rationalism were responsible for the arrival of modern technology, and he used that formulation to blame them for their own destruction. In the 1960s, Heidegger wrote:

When the essentially “Jewish” … in the metaphysical sense struggles against what is Jewish, the zenith of self-annihilation has been achieved. This means that the “Jewish” has, everywhere, appropriated for itself the mechanisms of domination, so that even the struggle against what is “Jewish” devolves into obedience to what is Jewish.

Heidegger, Wolin points out, was claiming that the Nazi modern machinery of destruction “had essentially resorted to Jewish methods.” And with such turns of phrase, Heidegger made his own distinctive contribution to obscuring Nazi Germany’s responsibility for World War II and the Holocaust.

Before the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg, Albert Speer, who became the Third Reich’s Armaments Minister during World War II, blamed the dangers of modern technology, rather than the decisions he and others had made, for the catastrophes of the war and the Holocaust. In the 1950s and ’60s, Heidegger’s criticisms of modern technology were offered as another example of a “belated pessimism” that presented the historically specific actions of the Nazi leaders as the tragic results of “planetary technology” or the abstractions of modernity. The bad habit of displacing proper nouns with universalizing abstractions was not Heidegger’s alone. It had leftist variations as well. Yet Heidegger’s distinctive contribution was to provide efforts to escape from the mundane but crucial facts of modern German history with a specious philosophical sophistication.

In the sixth and final chapter of Heidegger in Ruins, Wolin concludes by examining the enthusiasm for Heidegger among the Nouvelle Droit in France, the Neue Rechte in Germany, Alexander Dugin and the Putinist nationalists in Russia, the activists of the American far-Right, and right-wing terrorists denouncing the “great replacement” in Norway and New Zealand. Dugin, who has made the case for a Russian national socialism and for a “neo-Eurasian” policy of Russian territorial expansion, has published several volumes on Heidegger’s importance to Russia and the attack on Western liberalism. Wolin detects echoes of the moods and language of the conservative revolution of Germany’s 1920s in the nationalism and reactionary identity politics that have flourished in the West in recent years.

The value of Heidegger in Ruins lies in both Wolin’s original contributions and in his synthesis of a now large and increasingly critical body of scholarship, and it renders a devastating verdict. But the conclusion he asks us to draw “from these ongoing, contentious debates” is “not … that one should abandon Heidegger’s philosophy as irreparably contaminated and hence, irredeemable. Instead, Heidegger’s thought must be patiently and systematically reevaluated in view of the revelations of the Black Notebooks. … Heidegger in Ruins is intended as a modest contribution to a more demanding and long-term process of rethinking and reconsideration.”

But is this satisfactory? An array of historians and philosophers, including Wolin, compellingly argue that there was a clear connection between the concepts of Being and Time and Heidegger’s support for Hitler, that his support for Nazism never wavered, that his antisemitism shared the genocidal characteristics of Nazi ideology and propaganda, and that he was dishonest after the war about what Nazism was and about his own role in lending it respectability. If all of that and more is true, then surely it is long past time that we recognize Heidegger’s philosophy as “irreparably contaminated” with fascism and Nazism.

Rather than continuing to enjoy a reputation as one of the great European thinkers of the 20th century, Heidegger is more properly read as a paradigmatic case of an intellectual who despised liberal democracy and consequently betrayed the universities and his fellow scholars. The philosophizing that led him down this path should be treated with profound suspicion, not celebrated. Heidegger pressed the prestige he earned from Being and Time into the service of gutter hatreds, which he made respectable for the sophisticates of the lecture hall and the seminar room. He typified the search for respectability that the historian George Mosse has argued was a persistent yearning of fascist and Nazi intellectuals.

The case of Martin Heidegger, like that of Nazism in general, offers a warning about those intellectuals who seek global renewal through politics, and justify massive violence and barbarity to cleanse the world of its supposed degenerates. A Heideggerian element can be found in Putin’s revanchist dictatorship and in Iran’s antisemitic theocracy, both of which denounce the decadent West and celebrate martial virtues in pursuit of authenticity. The counter-Enlightenment has spread far beyond Europe, and has variations in the postmodernist Left as well as the far Right. Heidegger’s legacy may finally be in ruins, but the fascist attack on liberal democracy still has its intellectual advocates.

In synthesizing the work of decades, and drawing out the implications of new evidence, Richard Wolin in Heidegger in Ruins has produced a timely work of enduring importance.

UPDATE Feb. 24th: Vittoria Klostermann Verlag, the German publisher of the 102 volumes of Heidegger's collected works (the Gesamtausgabe), informs me that in 2013 it posted corrections of errors in twenty-six of the previously published volumes. Klostermann found the errors in volumes 39 (his university lectures of 1934–35) and 69 (Die Geschichte des Seyns [History of Being] written in 1939–40) to be so serious that it pulped these volumes and published revised corrected versions.

The fact that so many volumes needed corrections confirms the criticism of the original volumes voiced by Richard Wolin and other historians I mentioned in this essay. Faculty assigning works by Martin Heidegger at universities and colleges around the world should read Heidegger in Ruins, and other recent critical scholarship, before carefully scrutinizing the editions they are assigning in their courses. Students should not be misled by the earlier efforts to obscure or falsify the record of his Nazi era writings.