Politics

Fukuyama’s Victory

Liberal democracy has again proved itself capable of overcoming its internal challenges and contradictions.

I.

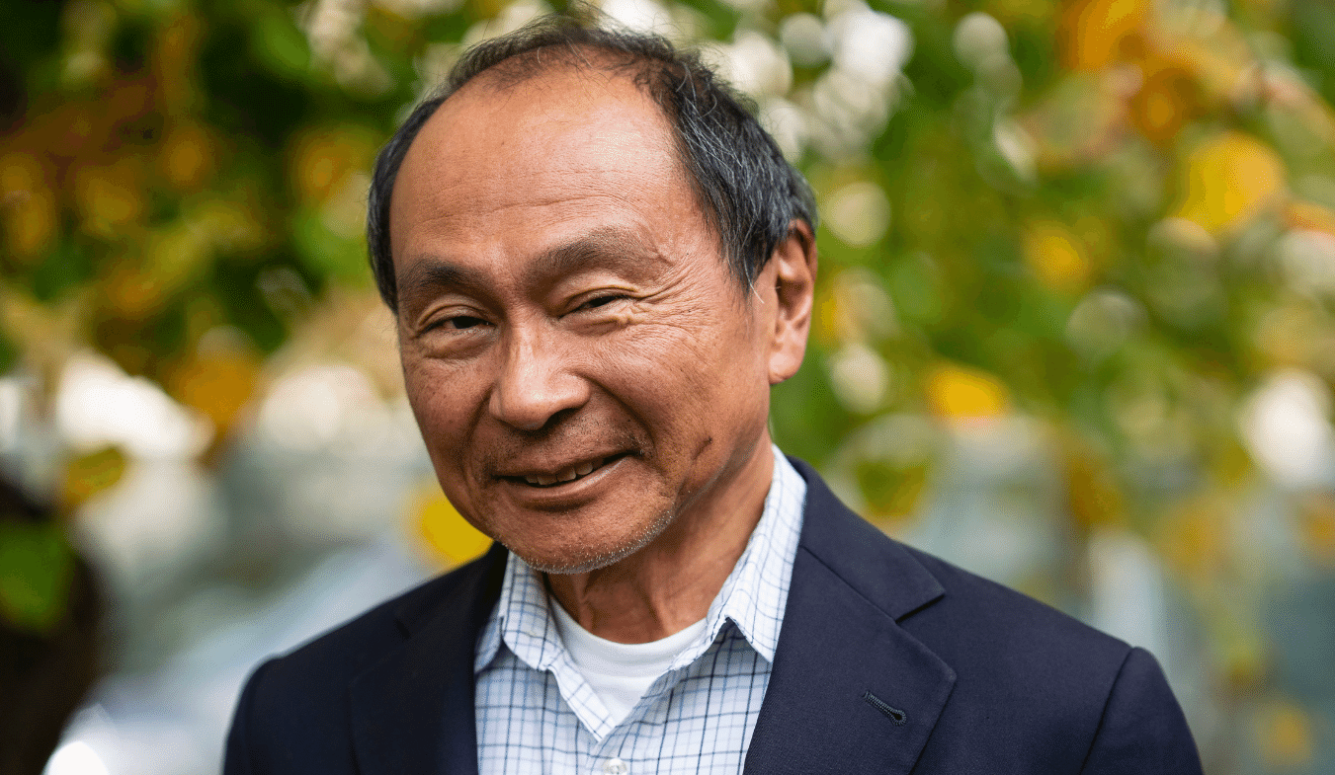

The memory of historical figures is often reduced to tidy declarative statements. Einstein discovered special relativity. Oppenheimer built the bomb. It’s difficult to think of many people living today (especially political scientists) who will have their own one-line historical summaries, but Francis Fukuyama is almost certainly one of them. He will be remembered as the man who declared the End of History.

The idea that history has an “end”—meaning a purpose or direction—was explored by the German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel when the modern liberal state was created after the French Revolution. Drawing on Hegel (particularly the Russian-French philosopher Alexandre Kojève’s interpretation of his work), Fukuyama introduced the concept to a wider contemporary audience in a 1989 essay in the National Interest titled “The End of History?” and expanded on it in The End of History and the Last Man, a book published in 1992. “The End of History?” was published on the 200th anniversary of the French Revolution and several months before the fall of the Berlin Wall, and it was astonishingly prescient. Fukuyama argued that the world was witnessing the “universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government,” a development that would “govern the material world in the long run.” A mere five years after “The End of History?” was published, the proportion of democracies in the world surged from less than 41 percent to over 54 percent. This ratio kept climbing until it was over 60 percent, where it remains today.

“The End of History?” is among the most widely misunderstood essays ever written. A common source of confusion is the idea that Fukuyama believed wars, political upheavals, and other historical events were coming to an end. He dispels this notion on the second page: “This is not to say that there will no longer be events to fill the pages of Foreign Affairs’s yearly summaries of international relations…” At the end of the essay, he reaffirms that his thesis “does not by any means imply the end of international conflict per se.” But this hasn’t kept his critics from declaring the thesis dead with the emergence of every new global crisis: on September 11th, during the Great Recession, when Trump was elected, when COVID-19 hit, when Russia invaded Ukraine.

Fukuyama argues that the victory of liberal democracy has taken place in the “realm of consciousness,” which means he recognizes that there’s a disconnect between the idea of liberal democracy and its manifestation in the real world. He didn’t argue that history would end within a particular time frame, nor did he say there would never be democratic reversals. He argued that liberal democracy would prove to be the most viable form of government over time—a thesis that’s just as plausible today as it was in 1989, if not more so. Catastrophes like Russia’s invasion of Ukraine demonstrate the durability of liberal democracy and support Fukuyama’s argument. The war is primarily a consequence of Vladimir Putin’s imperialist vision for Russia, as well as the lack of sufficient checks on his power. The same goes for China’s disastrous post-vaccination zero-COVID policy, which would be unthinkable in a democratic country.

Another stubborn misconception is the idea that the End of History is a triumphalist concept. Fukuyama laments what he describes as the “spiritual vacuity of liberal consumerist societies” and the “emptiness at the core of liberalism.” He says the “end of history will be a very sad time,” as the “worldwide ideological struggle that called forth daring, courage, imagination, and idealism, will be replaced by economic calculation, the endless solving of technical problems, environmental concerns, and the satisfaction of sophisticated consumer demands.” Fukuyama even admits that “I can feel in myself, and see in others around me, a powerful nostalgia for the time when history existed,” and he acknowledges that “nationalism and other forms of racial and ethnic consciousness” create fundamental challenges to liberalism.

However, Fukuyama doesn’t believe a strong sense of national identity is incompatible with liberalism. In his 2022 book, Liberalism and Its Discontents, he argues that it’s possible to build a national identity around liberal democratic principles. One of the main problems with this project is that liberalism isn’t a single cohesive ideology—Fukuyama defines it as a “big tent that encompasses a range of political views that nonetheless agree on the foundational importance of equal individual rights, law, and freedom.” Instead of galvanizing people around some ultimate political end—such as the dictatorship of the proletariat or the thousand-year Reich—liberalism offers the freedom to make your own decisions about who you want to associate with, what you want to express, and how to live a good life. A liberal society is capable of accommodating what John Rawls described as “reasonable pluralism”—diverse beliefs that can be freely held without impinging on the beliefs or actions of others.

While “The End of History?” isn’t exactly an inspiring tribute to the virtues of liberal democracy, Fukuyama appears to believe the possibility of boredom at the End of History is a small price to pay for the spread of liberal values. He contends that liberalism is the best way to maintain social peace in diverse societies, protect human dignity and autonomy, and promote economic growth. “Liberalism sought to lower the aspirations of politics,” he writes in Liberalism and Its Discontents, “not as a means of seeking the good life as defined by religion, but rather as a way of ensuring life itself, that is, peace and security.” Although the modesty of liberalism has made it a universalizable and sustainable social and political framework—it has lasted for hundreds of years now—this feature is also a bug when it comes to generating a strong commitment to liberal values. Members of the Muslim Brotherhood zealously tell their followers that “Islam is the solution,” while liberals can only weakly promise to create the conditions in which people can pursue whichever solutions work best for them.

II.

Liberalism and Its Discontents makes a cogent case for liberalism at a time when it’s under assault around the world, but Fukuyama’s Political Order series is in many ways the more natural sequel to The End of History. In the series’ first installment, The Origins of Political Order: From Prehuman Times to the French Revolution (2011), Fukuyama identifies the fundamental components of modern states: an effective central government, rule of law, and accountability. He explains how these components developed (or failed to develop) around the world. For example, China created a strong centralized state with an efficient and merit-based bureaucracy long before Europe, but failed to establish a consistent rule of law—partly due to its lack of a transcendental religion, which served to check the power of the state elsewhere in the world.

The Origins of Political Order is a sweeping tour of political development around the world, and it demonstrates how contingent different forms of development have been over the centuries. For example, Fukuyama cites the sociologist Charles Tilly’s maxim that, in many parts of the world, the “state made war and war made the state.” One of the reasons states like Prussia and China developed strong central governments was to mobilize their populations against constant attacks from their neighbors. This had implications for taxation, administrative capacity, and so on, and it was partially due to geography that was conducive to large-scale military mobility. On the other hand, Africa and Latin America present significant natural barriers to power projection, which contributed to the formation of weaker states.

Despite the divergent paths to state development—and the fact that many countries are still stuck with pre-modern elements of governance such as patrimonialism (which refers to states which are the personal property of a single ruler or elite)—Fukuyama observes that the essential features of a modern state are the same everywhere. He argues that the combination of an effective central government, the rule of law, and democratic accountability “produced a state so powerful, legitimate, and friendly to economic growth that it became a model to be applied throughout the world.” This is where the connection to The End of History is explicit. As Fukuyama explains in The Origins of Political Order:

Alexandre Kojève, the great Russian-French interpreter of Hegel, argued that history as such had ended in the year 1806 with the Battle of Jena-Auerstadt, when Napoleon defeated the Prussian monarchy and brought the principles of liberty and equality to Hegel’s part of Europe. In his typically ironic and playful way, Kojève suggested that everything that had happened since 1806, including the sturm und drang of the twentieth century with its great wars and revolutions, was simply a matter of backfilling. That is, the basic principles of modern government had been established by the time of the Battle of Jena; the task thereafter was not to find new principles and a higher political order but rather to implement them through larger and larger parts of the world. I believe that Kojève’s assertion still deserves to be taken seriously.

This is an ambitious claim, and it’s a reminder of why Fukuyama has accumulated so many critics over the years. Ideologues of all stripes despise him because he argues against any political philosophy which revolves around achieving some grand, ultimate end. He argues that liberal democracy will outlast any international working-class revolution, reestablishment of Christendom or the Caliphate, or return to an era of national glory and conquest. Even when there are outbreaks of violence and authoritarianism, liberal democracy has already won in the “realm of consciousness,” and it will continually prove to be a more compelling political ideal than its competitors.

Does this argument really stand up at a time when the Chinese Communist Party controls the second most powerful state on Earth and a Russian imperialist dictator is laying siege to Europe? The evidence continues to suggest that the answer is yes. It’s increasingly clear that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was an epochal mistake. Beyond the fact that the Ukrainian resistance has been far more resilient than Putin anticipated, the United States and its liberal democratic allies have responded by providing a huge influx of weapons and equipment, accepting millions of Ukrainian refugees, and imposing crippling sanctions on Russia (including on oil and gas, which has led to an energy crisis on the continent as winter approaches).

While China and India have maintained their economic relationships with Russia, both countries are growing impatient with the war, especially as Russian forces struggle on the battlefield and the global economic situation continues to deteriorate. During a meeting in September, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi told Putin “I know today’s era is not an era of war.” After his first meeting with Xi Jinping since the start of the war, Putin acknowledged that Beijing had “questions and concerns” about the war. When the G-20 recently met in Indonesia, members released a statement which condemned “in the strongest terms the aggression by the Russian Federation against Ukraine” and called for its “complete and unconditional withdrawal” from the country. While the statement noted that “most members strongly condemned the war” (which implies that the condemnation wasn’t unanimous), it was still viewed as a significant rebuke from China and India. Russia is failing in Ukraine and finding itself increasingly isolated.

Over the past few months, Ukrainian forces have reclaimed a huge amount of territory in the north-east and south of the country. These efforts recently culminated in the recapture of Kherson, the only provincial capital taken by Russia since the invasion and a critical element of Moscow’s plan to control the Black Sea coastline. Defeat looks likely for Russia, but no matter what happens on the battlefield in the coming months, Putin has succeeded in expanding and reinforcing NATO, strengthening European and transatlantic solidarity, and wholly discrediting his own leadership. The attractions of corrupt, militaristic, and backward petro-autocracy are few, so Russia won’t be challenging the prevailing liberal order any time soon.

The most serious challenge to this order is China. As Fukuyama explains: “How the new Chinese middle class behaves in the coming years will be the most important test of the universality of liberal democracy.” Fukuyama often draws a distinction between power and legitimacy. The Chinese government is extremely powerful, but the lack of accountability (in the form of democratic elections and other checks on the executive) means its legitimacy is derived from the state’s ability to deliver services and consistent economic growth. “The real test of the legitimacy of the Chinese system,” according to Fukuyama, “will come not when the economy is expanding and jobs are abundant but when growth slows and the system faces crisis, as it inevitably will.” China is undergoing this test right now.

Although the Chinese economy rebounded more quickly than expected in the third quarter (3.9 percent year-over-year), the country is on pace to have its slowest year of growth in almost half a century. China’s ongoing zero-COVID policy has been a major drag on economic performance, and hundreds of millions of Chinese have been repeatedly forced into lockdown while the rest of the world has opened up and largely brought the virus under control. Beijing faces a daunting set of other challenges: dangerously high youth unemployment, a demographic crisis that threatens to put immense strain on the healthcare system and public services, state interventions in the economy which have sapped investor confidence, and a failed economic strategy of government investment in the property sector. These crises are hitting at a time when Xi Jinping has just been confirmed for a third term (the former two-term, 10-year limit was scrapped in 2018). He has also filled the government leadership with loyalists and sycophants. If Beijing can’t get these systemic problems under control, the government’s legitimacy will suffer a serious blow. The consolidation of power in Xi’s hands will likely lead to poor decision-making, which will make the social, economic, and political crises in China all the more intractable.

Fukuyama describes Deng Xiaoping as “one of the greatest statesmen of the twentieth century.” After the trauma of the Cultural Revolution, Deng set in motion a series of reforms designed to prevent the emergence of another Mao—such as the term limits that Xi just discarded. Fukuyama explains that Deng “understood that the party’s survival would depend on legitimacy, which could no longer rest on ideology but would have to be based on their performance in governing the country.” Fukuyama argues that China became more law-governed in the decades after Mao, but never established a true rule of law or robust mechanisms for holding leaders accountable.

At the end of the Cold War, Fukuyama didn’t anticipate the political trajectory of Russia and China. Although he acknowledged that they were “not likely to join the developed nations of the West as liberal societies any time in the foreseeable future,” he also assumed that both countries would liberalize more quickly than they did. For example, he criticized those who believed Moscow’s behavior would “revert to that of nineteenth century imperial Russia.” While he acknowledged the “very strong current of great Russian chauvinism in the Soviet Union,” he also said it would be strange if Russia returned to “foreign policy views a century out of date in the rest of Europe.” Fukuyama likely would have been surprised that an ex-KGB dictator would, in the year 2022, launch the largest conflict in Europe since World War II in an effort to restore as much of the Russian Empire as possible. In his speeches and writings, Putin has been intensely critical of the Soviet Union as a disjointed and unsustainable supranational entity that wasn’t bound by the cultural and linguistic ties that once connected Russia and Ukraine.

In “The End of History?” Fukuyama observed that “Chinese competitiveness and expansionism on the world scene have virtually disappeared.” He wasn’t alone in assuming that economic liberalization in China would lead to greater political liberalization and global integration, and the latter half of this prediction has in many ways been realized. But Chinese expansionism today is largely attributable to Xi Jinping’s aggressive nationalism—another source of legitimacy in a state that lacks accountability or the rule of law. While Fukuyama may have been surprised by the reemergence of Chinese totalitarianism and imperialism more than three decades after the end of the Cold War, he has long argued that China’s hyper-centralized political system is vulnerable to the “bad emperor problem.” The ability to make and implement decisions quickly can lead to greater efficiency, but it can be catastrophic with the wrong leader in charge (which is why Deng was so focused on establishing formal political constraints after the nightmare of Maoism).

The natural temptation among Fukuyama’s critics is to view the direct assaults on liberal democratic principles from Russia and China as a negation of the End of History, but this isn’t just a misreading of Fukuyama’s argument—it’s a misreading of the political reality that confronts us. According to Fukuyama, “at the end of history it is not necessary that all societies become successful liberal societies, merely that they end their ideological pretensions of representing different and higher forms of human society.” Putinism isn’t animated by any great new idea like Marxism—all it offers is a crumbling kleptocracy and a foreign policy that has been deranged by one man’s chauvinism and hubris. The Russian “model” is rotting domestically and collapsing on the battlefield.

A similar authoritarian degeneration is visible in Iran—a country that has been in the grip of the largest protests since the 1979 revolution after the “morality police” arrested and killed a 22-year-old Kurdish woman named Mahsa Amini for allegedly wearing her hijab improperly. Amini was killed on September 16th, and the protests have persisted for months despite a brutal government crackdown. Attorney General Mohammad Javad Montazeri recently announced that Iran would abolish the morality police, an extraordinary concession that marks a victory for Iranian civil society that would have been difficult to imagine just months ago. While Amini’s death catalyzed the protests—which have been led by women and are primarily focused on women’s rights—Iranians are also furious with the government over perennial economic crises, fake “elections” that are determined in advance, and widespread corruption. It’s clear that a large proportion of Iranians are more secular and liberal than their government, which is why many of them don’t regard their theocratic system as legitimate.

China presents the only viable challenge to liberal democracy, but it’s difficult to imagine other countries emulating the Chinese model. As Fukuyama observes, China “invented the modern state at the time of the Qin unification, some eighteen hundred years before its rise in early modern Europe.” While China has gone through periods of what Fukuyama describes as “repatrimonialization”—when political favors and family ties undermine the administration of an impersonal and merit-based bureaucracy—the Chinese tradition of state-building has deep historical roots and can’t be easily replicated. Although Beijing is spreading its influence around the world, this is more a matter of constructing an international system that’s favorable to Chinese interests than exporting an ideology. China is still formally communist and all property technically belongs to the state, but it has also adopted many elements of a market-based system. Xi’s nationalism is a way to generate legitimacy in a society where the “consent of the governed” is a foreign concept, but it doesn’t position China as the leader of a global communist revolution. Maoism was an international movement during the Cold War, but there aren’t many Western intellectuals who describe themselves as Xiists.

III.

The final threat to liberal democracy comes from within. Fukuyama has long been concerned about political decay, and the internal threats to liberal democracy he identifies in his Political Order series have become increasingly dire over the past several years. In the United States, Fukuyama recognized that political polarization was causing gridlock and dysfunction before the Trump era. However, he couldn’t have foreseen the political violence on January 6th or that half the country would support an authoritarian president’s effort to overturn an election. Of all President Trump’s transgressions, his refusal to accept the results of the 2020 election was the most dangerous. It undermined faith in the most basic, centuries-old assumption of the American political system: that fair democratic elections will result in the peaceful transfer of power. Beyond the immediate chaos this caused—from the January 6th insurrection to the coordinated campaign to pressure election officials, state lawmakers, members of Congress, and even Vice President Mike Pence to overturn the election—Trump’s rejection of the results has established a new anti-democratic norm in the United States.

When Kari Lake lost the Arizona gubernatorial race, she immediately challenged the results and filed a public records lawsuit demanding that Maricopa County provide election documents. A recent New York Times analysis found that significant proportions of Republican state lawmakers had “taken steps, as of May 2022, to discredit or overturn the 2020 presidential election results”: 48 percent in Michigan, 73 percent in Wisconsin, 78 percent in Pennsylvania, and 81 percent in Arizona. Now that the norm of election integrity has been violated at such a high level, it could take years or even decades to reestablish.

A major theme of the Political Order series is the importance of establishing impersonal state institutions. This is an arduous process, as human beings are naturally inclined to privilege the interests of their own groups over the interests of the country. Fukuyama argues that political patronage and clientelism are natural outgrowths of “political mobilization in early-stage democracies.” The US government was a patronage system from the very beginning, as presidents including Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe appointed political allies—who typically had high levels of education and social status—to positions of power. The election of Andrew Jackson in 1829 brought the spoils system into existence, a process Fukuyama describes as the conversion of an “existing elite patronage system into the beginnings of a mass clientelistic one.” When the franchise expanded, politicians and political machines around the country bought votes directly with promises of jobs, government appointments, and other benefits. The patronage system became more organized and entrenched later in the 19th century, but the assassination of President James A. Garfield by a mentally deranged office-seeker shifted public sentiment against the spoils system. The passage of the Pendleton Act in 1883 set the United States on a decades-long course of civil service reform, which ultimately resulted in the establishment of a more modern, less clientelistic state.

The thread that connects Fukuyama’s arguments in the Political Order series and more recent books like Identity: Contemporary Identity Politics and the Struggle for Recognition and Liberalism and Its Discontents is the breakdown of the broad liberal consensus in many Western societies. Beyond the structural problems Fukuyama identified in Political Order and Political Decay (such as powerful interest groups manipulating the formation and implementation of public policy), the rise of populism, nationalism, and other forms of identity politics has created hostility to liberal values on the Left and Right.

Recall that liberalism is built upon inclusive ideas such as reasonable pluralism. Nationalist movements like Trumpism reject these ideas in favor of a narrow conception of citizenship which includes some Americans and excludes others. This is why Trump waged a relentless campaign against Muslim Americans, told Democratic Congresswomen to “go back and help fix the totally broken and crime infested places from which they came,” and spent much of his presidency attacking immigrants (rhetorically and with measures like the Muslim ban and child separation policy at the southern border). Other nationalist leaders such as Hungary’s Viktor Orbán—as well as the most popular Trumpist media demagogues like Tucker Carlson—share this obsession with immigration and demographic change. The populist Right is far more concerned with immigration and cultural conflict—over critical race theory in schools or trans issues, for instance—than the corrosion of democracy driven by figures like Trump, Lake, and election deniers across the country.

Many on the Left have embraced their own brand of identitarianism. Race, gender, and sexuality have become critical variables for many Democratic voters, and when politicians suggest that candidates should be selected on the basis of their positions and principles (as Senator Bernie Sanders did at the beginning of the 2020 primaries), they often receive intense pushback. A core feature of liberalism is individualism—the idea that nobody should be judged on the basis of their group identity. Popular left-wing intellectuals and politicians have inverted this principle, arguing that some voices should be amplified and others discredited because the person speaking has the right or wrong race, gender, etc. When Sanders called for a “non-discriminatory society which looks at people based on their abilities, based on what they stand for,” he became the target of widespread scorn and ridicule.

Although Identity and Liberalism and Its Discontents are Fukuyama’s direct replies to the creeping illiberalism spreading throughout the democratic world, his Political Order series offers deeper insights into the causes of (and solutions to) this malaise. Because the essential components of modern liberal democracy are the same everywhere—a centralized impersonal state, the rule of law, and accountability—it’s possible to identify the most pernicious threats to democracy generally. The threat that Fukuyama emphasizes most often in the Political Order series is repatrimonialization—when the impersonal state is captured by rent-seeking elites. Fukuyama argues that this form of political decay is “never finally solved in any political system,” because the “reliance on friends and family is a default mode of human sociability and will always return in different forms in the absence of powerful incentives to behave otherwise.” Fukuyama directs this critique at elites who “use their superior access to the political system to further entrench themselves, their families, and their friends…” However, Fukuyama provides a broader way to think about repatrimonialization which is more relevant today:

Modern liberal democracies are no less subject to political decay than other types of regimes. No modern society is likely ever to fully revert to a tribal one, but we see examples of “tribalism” all around us, from street gangs to the patronage cliques and influence peddling at the highest levels of modern politics. While everyone in a modern democracy speaks the language of universal rights, many are happy to settle for privilege—special exemptions, subsidies, or benefits intended for themselves, their family, and their friends alone.

Fukuyama cites three major examples of repatrimonialization in The Origins of Political Order: the recapture of the first modern and impersonal state by powerful families in the Later Han Dynasty in China, the patronage system developed among Mamluk slave-soldiers which contributed to their defeat at the hands of the Ottoman Empire, and the political influence of venal officeholders in Ancien Régime France. In each of these cases, repatrimonialization was a process driven by elite manipulation of the political system. The difference in liberal democracies today is that we seem to be witnessing the patrimonialization of everything—elites are often responding to the tribal demands of millions of citizens. Tribalism has become a more significant force at every level of the society, not just among the elites.

This is a departure from more traditional forms of patrimony. In the United States, patronage cliques and influence-peddling have always been powerful forces in politics. When interest groups and narrow constituencies acquire too much influence, they have an outsize impact on the formation and implementation of public policy. But this is hardly comparable to an outgoing US president attempting to destroy the most basic pillars of democracy and doing so with the support of much of his party and millions of voters. Nor is it comparable to the competing forms of identity politics that have deranged American civic discourse on a massive scale.

IV.

A central theme of The End of History and the Last Man—one which permeates Fukuyama’s later work—is that the desire for recognition is a basic human need and (according to Hegel) the fundamental driver of history. This desire can lead to great moral advances, such as the Civil Rights Movement, when black Americans demanded dignity as free and equal citizens. But the desire for recognition can also be a source of hatred and oppression, such as when the Nazis demanded recognition as a superior race. The desire for recognition is linked to the ancient Greek concept of thymos, which translates roughly as “spiritedness” and refers to a sense of dignity and self-worth. Fukuyama describes thymos as the “psychological seat of Hegel’s desire for recognition,” and he draws a distinction between isothymia and megalothymia—the desire to be recognized as equal versus the desire to be recognized as superior. In The End of History and the Last Man, Fukuyama cites Donald Trump as a man whose megalothymic desires were at that time being channeled into the relatively benign pursuits of property development and the accumulation of wealth. Fukuyama doubted that the recognition Trump received and the sense of accomplishment he felt would be “ultimately satisfying for the most thymotic natures.”

Megalothymia is a characteristic of most dictators and would-be dictators. While The End of History and the Last Man is often associated with the fall of the Soviet Union, Fukuyama opens the book with a series of pre-1989 democratic revolutions and transitions around the world. In Portugal, Greece, Spain, Peru, Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil, Chile, the Philippines, South Korea, Taiwan, Burma, South Africa, and elsewhere, there were major shifts toward democracy in the 1970s and 1980s. Countries like Portugal and Spain saw surprisingly peaceful transitions to democracy, as dictators willingly stepped aside in the face of overwhelming democratic sentiment. “We have had difficulty perceiving the depths of the crisis in which dictatorships found themselves,” Fukuyama writes, “due to a mistaken belief in the ability of authoritarian systems to perpetuate themselves, or more broadly, in the viability of strong states.”

Fukuyama argues that “all regimes capable of effective action must be based on some principle of legitimacy.” Many of the authoritarian governments cited above lost their legitimacy due to economic pressures or social unrest, which hastened the transition to democracy. In most cases, their leaders’ megalothymia wasn’t strong enough to make this process particularly violent or arduous. It’s extremely difficult to imagine a similar process taking place in today’s China. Xi’s megalothymia appears to rival Mao’s—he has constructed a nationalistic cult of personality reminiscent of the 20th-century dictatorships in Europe and Asia. Although it’s easier to imagine a coup or some form of political upheaval that would remove Putin, this process would likely be bloody and chaotic, unlike the democratic transitions in Europe, South America, and Asia in the second half of the 20th century. The megalothymia that motivates Xi and Putin won’t be easily cast aside.

But both governments are still facing their most severe crises of legitimacy in decades. The self-inflicted consequences of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine are mounting by the day, while the pact between the CCP and the Chinese population—stability and economic growth in exchange for freedom—is beginning to unravel. As I was writing this article, the largest Chinese protest movement in decades swept through dozens of cities after a fire in Urumqi killed at least 10 people, a tragedy many Chinese attribute to lockdown measures which trapped the victims in the burning building. This all but forced public officials across the country to ease COVID-19 restrictions. Although the government has responded with its usual brutality in suppressing the protests, the decision to adjust COVID policies undermines the CCP by calling those policies into question. This is a blow to Xi’s legitimacy, as he made zero-COVID such a critical measure of the state’s effectiveness. Meanwhile, the scale of the protests required a much wider crackdown, which exposed a broader swath of the Chinese population to the government’s totalitarian intrusions. As the New York Times reports, the government’s response to the protests marks the “first time the surveillance state has been directed squarely at large numbers of middle-class people in China’s most affluent cities.”

It would be naive to hope that China is on the verge of a dramatic social and political transformation, but unrest is mounting in the country. This isn’t just a result of the government’s mishandling of COVID-19, it’s a result of many systemic factors that will plague the country for decades to come. But more fundamentally, it’s a crisis of legitimacy in a one-party state that is struggling to perform well enough to justify its suffocating grasp on the population.

Despite the evidence of political decay in liberal democracies over the past several years, democratic governments and societies have proven more resilient than their authoritarian enemies expected. Putin’s invasion of Ukraine was met with the strongest display of European and transatlantic unity in decades. The authoritarian response to COVID that China could boast about two years ago has turned into a humiliating nightmare for its government and people, as democratic countries manage the disease and return to normal while Chinese citizens continue to suffer under oppressive and economically devastating restrictions. (Amid the outrage over the fire, many Chinese have also expressed frustration at the footage of unmasked football fans at the World Cup—the sort of event they’re unable to attend.) Most importantly, democratic procedures and institutions have proven their durability during a series of authoritarian onslaughts from within, particularly in the United States, but also in Brazil and elsewhere around the world.

When Trump attempted to overturn the results of the 2020 election, his lawsuits were thrown out by the courts, Congress certified President Biden’s victory, and the Department of Justice is now investigating the former president over his efforts to subvert the electoral process and the political violence on January 6th. A bipartisan House committee is conducting a simultaneous investigation, and its findings have been shared with the American people. But the most important rebuke of Trump has been at the ballot box: Biden defeated him by 74 electoral votes and more than seven million popular votes. Democrats performed much better than expected in the 2022 midterms, and many Trump-backed candidates who cast doubts on the 2020 election—including those running for attorney general, secretary of state, and other offices which have a supervisory role over elections—underperformed across the country.

The effort to steal the 2020 election was alarming, but it failed. Unlike Iranian theocracy, Putin’s moribund petro-autocracy, or Chinese totalitarianism, liberal democracy has once again proved itself capable of overcoming its internal challenges and contradictions. This is why democracy has survived for hundreds of years, while its authoritarian rivals have always collapsed under the weight of their own hubris and cruelty. When this inevitably happens again, maybe we’ll revise that one-line biography: from Fukuyama declared the End of History to Fukuyama was right.