Politics

The Loneliness of the ‘Bridge Man’ Generation

China’s dissenters are isolated. But they are not as isolated as they once were.

I thought to myself that there are many Chinese who also want freedom and democracy. But where are you? Where can I find you? If we meet on the street, how can we recognize each other?

~“Kathy”, a Chinese student in London

It’s been a month since the Sitong Bridge Protest, and while many people within China have never heard of the “Bridge Man,” there are already signs of the popular revolution he wanted. The country’s Zero-COVID policy is approaching a breaking point. Riot squads and water cannons were deployed in Guangzhou after citizens forced their way out of lockdown, dismantled COVID control barriers, and tipped a police van onto its side—years of frustration giving way to delirium. There have been similar scenes of chaos in Zhengzhou, along with protests in Nanjing, Lanzhou, and Chongqing. The nation’s capital is newly locked down, and already public discontent is simmering there.

Ürümqi, meanwhile, has been under the heaviest restrictions for more than three months, and on November 24th, the residents of a high-rise building burned to death in a fire. For them, as for many Chinese over the past three years, lockdown meant being literally locked inside by the authorities. And despite the fact that the Party is attempting to suppress the news of this tragedy, everyone I speak to in China seems to know all about it. In Ürümqi, incensed crowds are defying restrictions to protest. From Chengdu in the West to Shanghai in the East, they are gathering to call for Xi to step down—an unprecedented escalation.

Many, of course, will wait patiently at home, trusting the authorities to do the right thing. But even the faith of model citizens like these is now being shaken. They have seen, on their television sets, a vivid glimpse of the world outside China. To their surprise, it looks nothing like the world they live in: a global football tournament with no mandatory masks, no social distancing, no exhausted queues outside testing stations, and no sign of the hazmat-wearing stormtroopers the Chinese call “Big Whites.” The contrast is jarring.

The longer the Zero-COVID policy persists, the heavier the strain on that central pillar of CCP indoctrination—“the Party and the people are one.” Life has become absurd for Chinese citizens; for many it has become tragic. They can’t hide forever from the fact that someone is inflicting this state of affairs on them, and even the most devout of believers will surely begin to doubt that it’s all just another American plot (a well-worn trope). For now, their rage is directed at a policy. But as the protests are quashed and the policy continues, it will seem more reasonable for them to direct that rage at the policymakers. We shall see.

Outside China’s borders, Bridge Man is better known, and Chinese dissidents have wider grievances than Zero COVID. A group of anonymous dissidents has been using the Instagram account CitizensDailyCN to keep track of anti-Xi posters seen in public in recent weeks. One of the admins for CitizensDailyCN suggests that posting the banners alerted China’s overseas dissidents to one another’s existence: “the first step towards building a community.” The next step came quickly, as CitizensDailyCN launched Telegram chat groups in various cities around the world. Telegram was chosen because it allows users to delink numbers from names, making it harder for the Party’s ubiquitous spy networks to track people down.

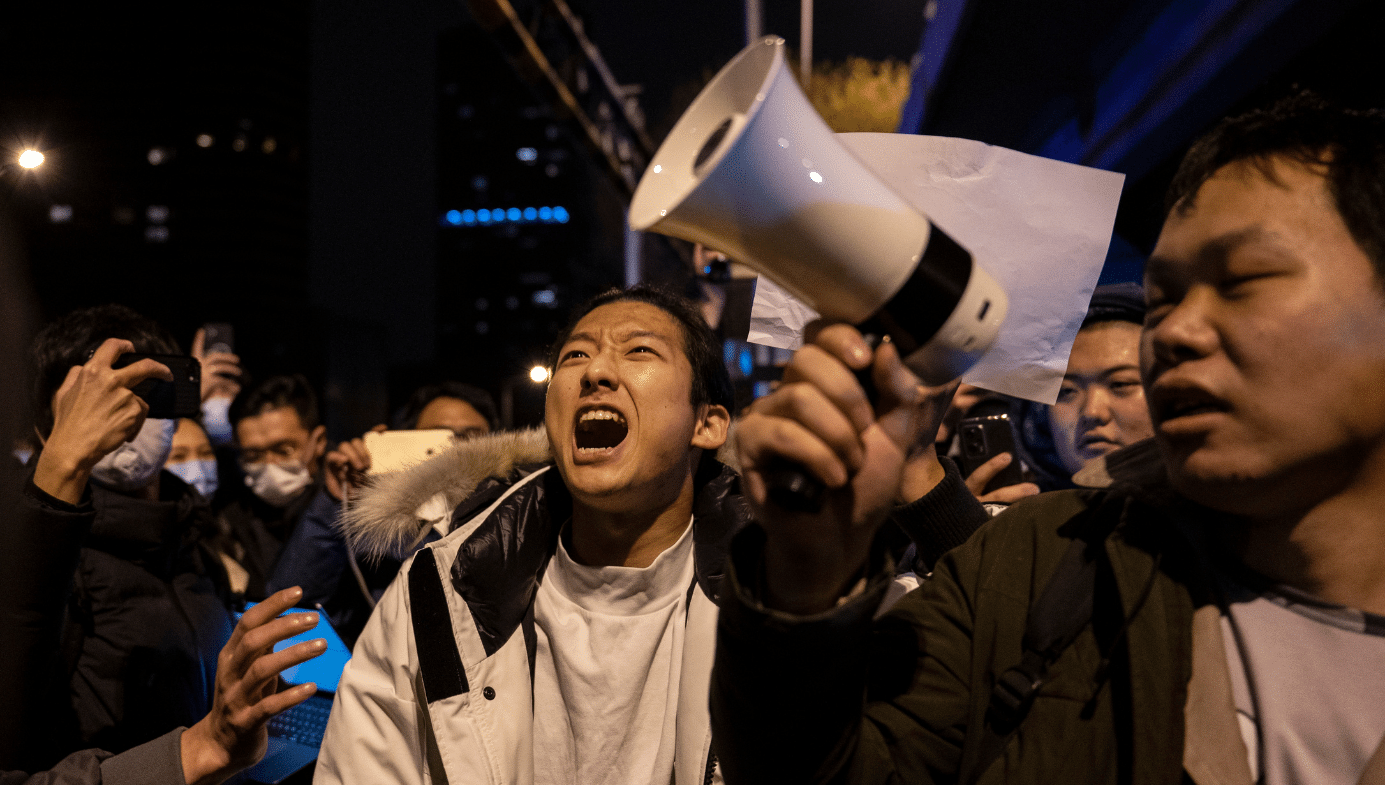

Thousands of Chinese students have joined these chat groups, revelling in the opportunity to exchange views critical of the CCP. Now the chats are being used to organise anti-Xi protests in cities around the world. These protesters are emblematic of the emerging Bridge Man Generation: people were already angry, but it took his sacrifice to galvanise them. And so, in New York on Hallowe’en, students slipped into Big White bodysuits—a mockery of the COVID security teams back home and a precaution against identification—and marched through the streets calling for an end to Xi Jinping’s rule.

On crowded Western university campuses, members of this Bridge Man Generation jostle and rub shoulders with some very different Chinese groups. Party members; rabid nationalists; spies (the Ministry of State Security fills academic institutions with its agents). There is also the Xiao Fenhong, the “Little Pink,” a particularly vile species that metastasised over a decade ago at the Jinjiang Literature City website. Chinese students, mostly female, began ferociously attacking any posts they thought painted China in a less-than-entirely-positive light. They named themselves after the colour on Jinjiang Literature City’s main page, and over time the term “Little Pink” came to encompass all young Chinese women behaving in the same way. The Little Pink lie in wait for a heretical comment, at which point they flood social media accounts with abuse. I picture them as a horde of tiny demonic children screaming and swarming over the unfortunate netizen.

In New York, freshman Wang Miao told Grid how she had hurried to pin up a poster in her student union, showing Xi Jinping with the legend “Dictator Out!” She kept one eye all the time on her Little Pink friend, who was speaking to a tutor with her back turned. Nationalists like Wang’s friend will have scant notion of these new heretics within their midst: the students who walk among them, accompanying them to classes and restaurants and parties, outwardly the same as everyone else, inwardly harbouring the most epochal thoughts. And while Western students imagine themselves to be suffering endless gender-related trauma, Chinese students like Wang live a truly fraught existence. Had her friend turned round at the wrong moment, a single glance could have changed Wang’s life forever. One phone call to China would bring the police to her parents’ doorstep. Wang may have lost the chance to ever see home again. Students speak of friends who returned to China only to find the dreaded police cordon waiting for them at the airport: some have decided, understandably, not to go back.

How far does the discontent spread? Every single mainlander I’ve spoken to in the past year has been opposed to Zero COVID and—more significantly—to Xi Jinping himself. Their mood is defeatist rather than revolutionary. They see no hope at all. But I certainly see hope, because there was none of this frank dissatisfaction just a few short years ago. The true numbers are hard to gauge. I recall asking one fervently anti-CCP Chinese woman (she called Party leaders “devils”) how many friends she could speak to about politics without censoring herself. “Like three to four,” she replied. For context, she told me she had around 50 friends.

Of course, the populace does not slice cleanly into “brainwashed” and “unbrainwashed.” As I’ve argued elsewhere, the Communist Party’s indoctrination system usually produces scattershot results. The majority of citizens pick and choose from the propaganda to fashion a personalised belief system. But still, a significant minority believes it all. Another significant minority manages, heroically, to see through the whole thing. So was my friend’s experience representative? Just six percent of the nation’s minds are free?

“Kathy,” a member of the Bridge Man Generation newly arrived in London, estimates that the figure is probably closer to three percent. As she explained (pseudonymously, of course) to the New York Times, she can talk about politics to just one in 30 of her classmates back in China. Most of the time, Kathy’s friends are “normal people, even kind.” But as soon as Nancy Pelosi visited Taiwan, “a program embedded in the robots was turned on,” and “everyone started posting the same horrible language on social media.” I saw it myself: gentle and kind-hearted acquaintances taking to the Chinese apps to shriek and lament that the People’s Liberation Army had failed to shoot down Pelosi’s plane—genuinely upset that an elderly woman had not been murdered.

The existence of CitizensDailyCN has convinced Kathy that there must be plenty of Chinese like her in London. But how to find them? The Telegram groups are full of pseudonymous users, for reasons of safety. Kathy managed to join the London protests, where she listened with terror and elation to other masked Chinese chanting Bridge Man’s slogans. She shivered with fear, she cried, and then she joined in. True courage, as they say, is not the absence of fear, but the decision to act even when afraid.

This question of the charged divisions in Chinese society recalls the Foshan tragedy of a decade ago—an incident that, at the time, seemed to quantify the moral decay in modern China. On October 13th, 2011, Wang Yue, aged two, wandered into a road in Foshan city and was hit by a van. The driver paused with her body still lying between his front and rear wheels, as if unsure of what to do, and then simply drove over her again and sped off. Within a minute, a second vehicle crushed her legs and also failed to stop. As the toddler lay mangled and dying, 18 people passed her. Cyclists glanced and swerved; pedestrians stepped over her body—it was like some darker Chinese retelling of the Good Samaritan story.

Finally a rubbish scavenger came to her aid. But by this point it was too late, and Wang Yue succumbed to her injuries in hospital. The tragedy caused outrage and some very public soul-searching, suggesting the existence of plenty of people with an active conscience. And yet there is no getting away from it: when actually placed in that situation, out there in the streets of Foshan rather than sitting behind a keyboard after the fact, only one person did the right thing. Some commenters appealed to a famous case in which a Chinese citizen had tried to help the victim of an accident and ended up being forced to pay the medical bill. People are afraid, so the argument went. But this does not solve the problem. Twenty individuals each made the same astonishing personal decision that the life of a child was not worth the threat of a medical bill. How can we explain it?

It was hardly a one-off: on the same day that Wang Yue was run down, a Uruguayan expatriate was forced to dive into a lake in Hangzhou to rescue a woman attempting suicide. Chinese bystanders were lining up at the lakeside to photograph the woman as she was drowning, and the Uruguayan realised that she needed to act because no one else would. Even as she hauled the victim out of the water and up an embankment, no one assisted. Instead, they filmed the scene on mobile phones and iPads. Just weeks later, down on China’s east coast, a five-year-old was struck on the head by a wooden beam falling from a construction site. The boy’s mother pleaded with passing drivers, pedestrians, and police officers to take him to hospital. All ignored her. The boy died.

Now, I don’t know the political opinions of the Foshan rubbish scavenger, but I’m tempted to equate the minority who would help a dying stranger with the minority who would reject all state indoctrination. Disregard for the individual is something learned in childhood, via the anti-human philosophy of collectivism which authorities have the nerve to call a “Chinese tradition.” It’s just another part of the brainwashing; it all spews from the same source. Those who manage (for whatever reason) to distrust their education will also manage to hold on to their natural human feeling.

“I lost my idea of the gentleness of human flesh,” laments the Nazi protagonist of Time’s Arrow by Martin Amis. “We lost our feeling about the human body. Children even. Tiny babies.” This is what we see in modern China—ideology leaves little room for empathy. But I believe the idea of the gentleness of human flesh can be recovered. We might imagine, once the Party falls, that it will take decades to repair the damage done to the nation’s psychology. And yet progress can be made surprisingly quickly in the age of the Internet. We saw an example two years ago, when Chinese citizens began using Clubhouse (an app that allows thousands of users to join the same audio chat room). Authorities were slow to catch on to Clubhouse, and so mainlanders had an unexpected window to the real world. They listened as Uyghur users told the truth about the Xinjiang genocide, describing their relatives’ personal experiences in the concentration camps.

Young Chinese broke down and cried, and Uyghurs cried with them. Reality was suddenly unfiltered; undiluted. The iron mind grip was gone. With no Party presence to tell people how to process this shocking new information (how to think about it “correctly”), ordinary human beings found themselves free to recognise the humanity in one another. Some stated frankly that their belief in the government had collapsed. Soon enough the authorities became aware of what was happening, and Chinese users found they could no longer log in to Clubhouse. But there is tremendous hope to be drawn from this brief episode.

Indeed, historian Taisu Zhang has expressed his surprise at how “brittle” Chinese nationalism has proven in the face of socioeconomic upheaval: “If my Weibo feed (which includes most of the major nationalist public intellectuals) is any indication, [nationalism]’s been forced into a defensive posture far more swiftly than its near-total domination over the last two years could have reasonably suggested. … It seems that online Chinese nationalism doesn’t have a very high pain tolerance.” Zero COVID is ramping up the pain, and people are losing their faith. The apostate numbers will only grow. For now, China’s dissenters are still isolated. But not as isolated as they once were.