Education

Sex and the Academy

The inclusion of women in higher education is a great achievement for Western liberal societies. How is this changing academic culture?

Psychologists and other social scientists have been studying human sex differences for 100 years, and in recent decades have demonstrated that many of the differences that emerge in Western cultures are found in every other culture in which they have been studied.

~Dave Geary

We are in the middle of a great social experiment. The sex ratios of many important institutions in the West are changing, and few institutions more dramatically illustrate this shift than academia. For centuries, academia was primarily a male-led institution. Although many universities in the United States began admitting women in the 1800s, others did not begin to do so until the mid-to-late 1900s.

Only in the past few decades have women started to outpace men at all levels: new bachelor’s degrees, new graduate degrees, new faculty members. Today, an institution once led and populated almost entirely by men, is increasingly led and populated by women. Because men and women (on average) have different traits, tendencies, and priorities, this change in sex ratios has changed and will continue to change the nature of the modern university.

Evidence for the Changing Sex Composition of Academia

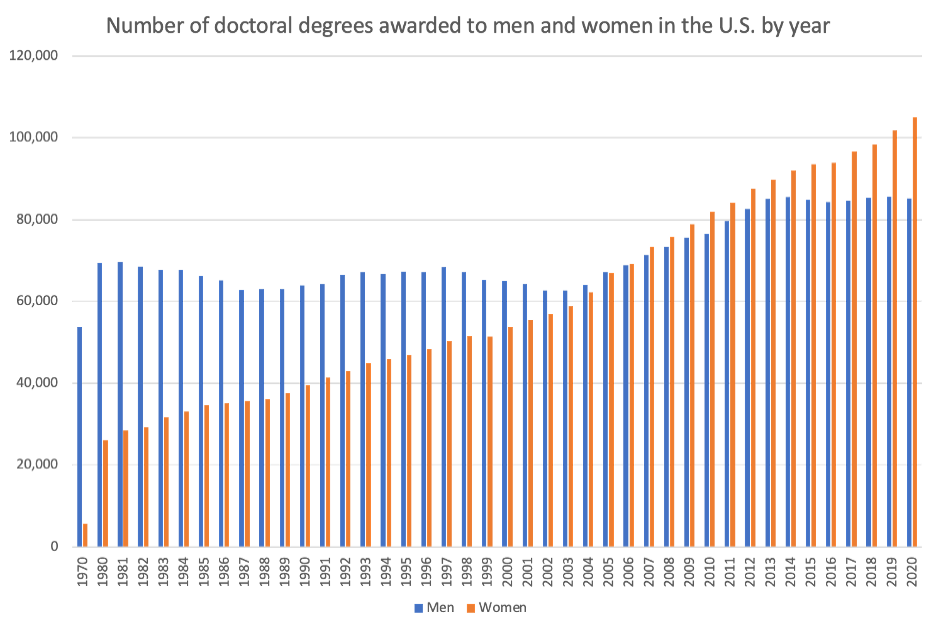

In 1970, women received less than 10 percent of doctoral degrees awarded in the United States. This percentage has steadily increased, reaching parity with men around 2005. Today, the majority of new doctorates are earned by women. Similar patterns pertain elsewhere, including in Australia and many European countries.

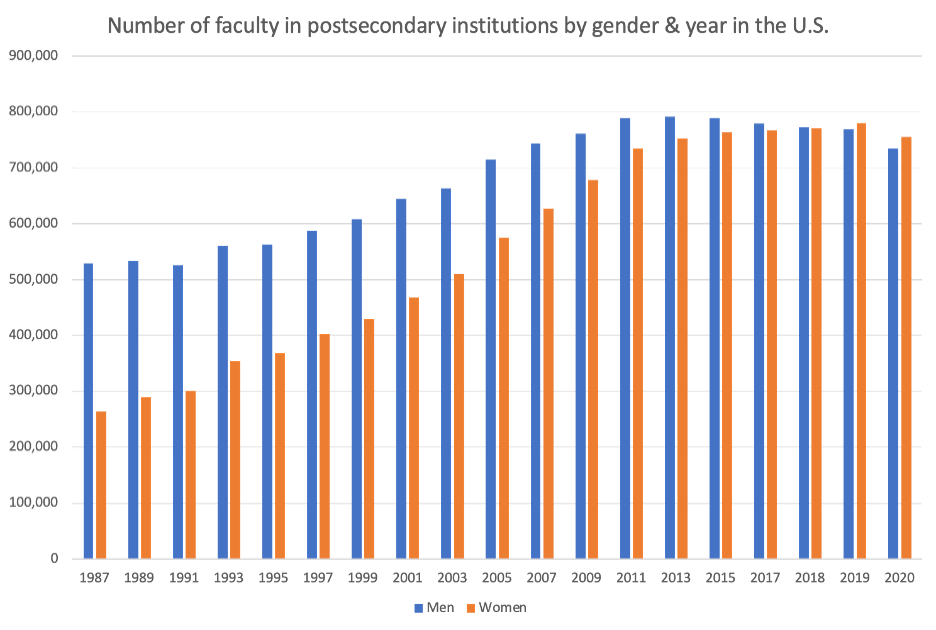

In 1987, less than a third of faculty at postsecondary institutions in the United States were women. Today, 50.7 percent are. In the coming years and decades, this percentage is likely to grow. One way to predict future trends (albeit imperfectly) is to look at the percentage of men and women at different career stages: older cohorts retire and are replaced by new ones.

As of 2020, men made up about 63 percent of full professors, about 52 percent of associate professors, and about 45 percent of assistant professors. Among scholars employed at universities and four-year colleges in 2019 in science and engineering disciplines, faculty with 30 years of experience or more were about 25 percent female, and faculty with less than 10 years of experience were about 42 percent female. Across biological and life sciences, computer sciences, mathematical sciences, physical sciences, psychology, social sciences, and engineering, the percentage of female faculty with less than 10 years of experience is 1.6 to 4.8 times higher than the percentage of female faculty with 30 years of experience or more.

If current trends persist, women will gain increasing influence over the direction of the university.

The inclusion of women in higher education is a great achievement for Western liberal societies. Women are now supported and encouraged to pursue their intellectual interests, and it is clear that when they do, they excel. These societies now benefit from the many contributions of women in the sciences and humanities. And indeed, many have argued that the inclusion of women in formerly male-dominated fields has broadened the scope of inquiry and shed light on once-mysterious or hitherto neglected phenomena.

So, how are these changes impacting academic culture—its priorities, policies, and norms—and shaping the direction of higher education and science? It is increasingly evident that men and women view the purpose of higher education and science differently, and that many emerging trends in academia can be attributed, at least in part, to the feminization of academic priorities.

Evidence for Gender Differences in Academic Priorities

Numerous surveys over the past five years have found large and consistent differences in the preferences and priorities of men and women, and these differences cohere with a broader pattern of evolved traits and tendencies.

A 2017 YouGov survey of 2,300 US adults on issues related to free speech and tolerance on college campuses (weighted to be nationally representative) found that:

- 56 percent of men said that colleges should not protect students from offensive ideas; 64 percent of women said that they should.

- When presented with a variety of controversial claims made by speakers (e.g., men are better at math, all white people are racist, police are justified at stopping African Americans at higher rates), a majority of men supported nine of the 11 speakers’ right to speak on campus, and a majority of women opposed all 11 speakers’ right to do so.

- 51 percent of men said colleges should not disinvite speakers if students threaten violent protest; 67 percent of women said they should.

- 58 percent of men opposed a confidential reporting system at colleges which students could use to report offensive comments; 54 percent of women supported it.

- 63 percent of men thought controversial news stories in student papers should not need administrators’ approval before publication; 51 percent of women thought they should.

- 65 percent of men believed that supporting the right to make an argument is not the same as endorsing it; 51 percent of women disagreed.

A 2021 survey of 3,772 academics and PhD students at universities in the United States, Britain, and Canada conducted by the Center for the Study of Partisanship and Ideology found that:

- 66–76 percent of men support intellectually foundational texts above diversity quotas on reading lists; 44–66 percent of women support diversity quotas above foundational texts.

- Female academics report a greater willingness than their male counterparts to support dismissal campaigns against a colleague who has conducted research that reached a controversial conclusion.

A 2018 Knight Foundation survey of 4,407 full-time college students on issues related to free expression on campuses and diversity and inclusion found that:

- 71 percent of men reported that protecting free speech is more important than promoting an inclusive society; 59 percent of women said promoting an inclusive society is more important than protecting free speech.

- 58 percent of men said it is never acceptable to shout down speakers or to try to prevent them from delivering their remarks; 58 percent of women said it was sometimes or always acceptable.

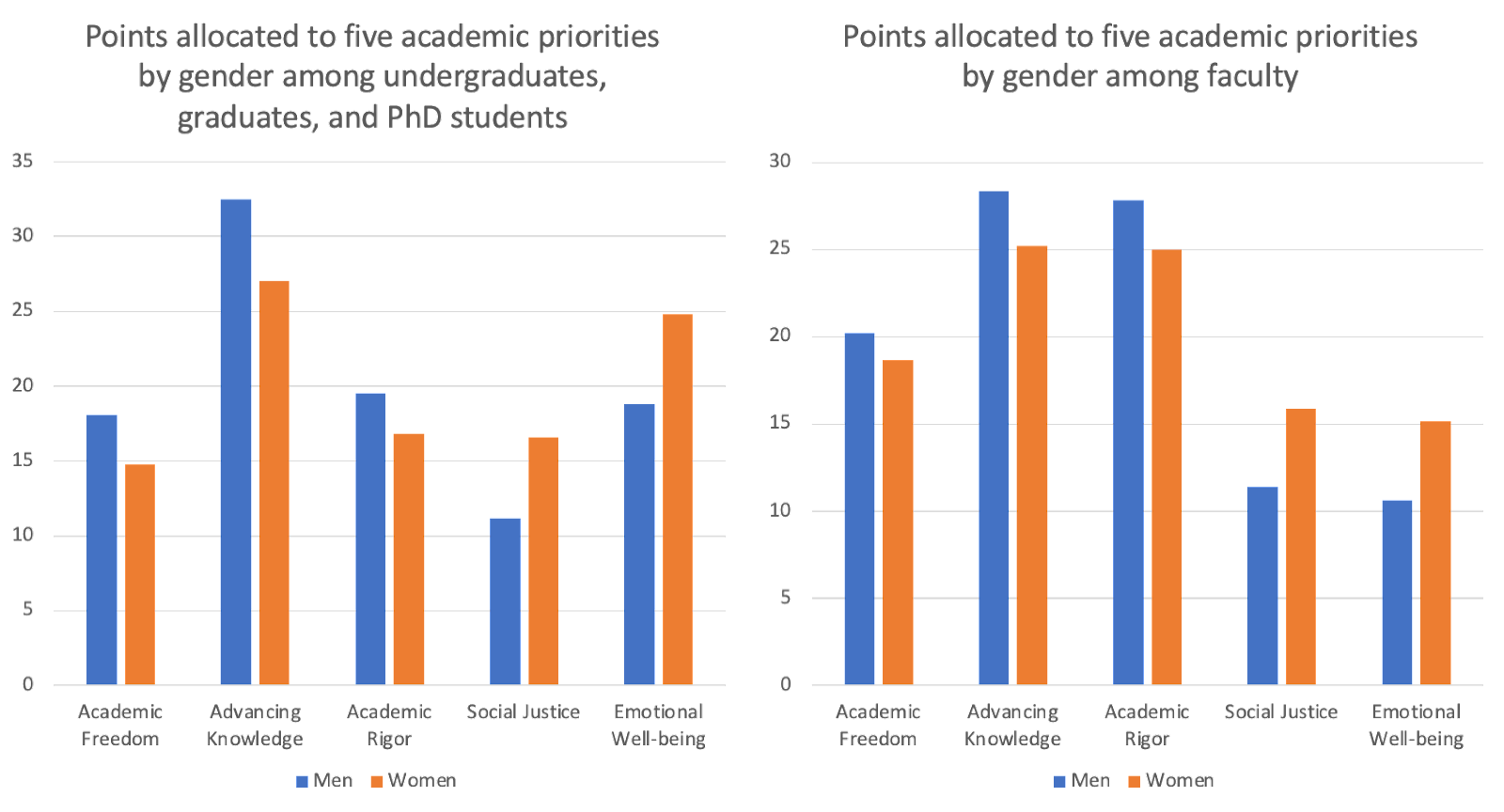

A 2022 paper by Rausch and colleagues (in press at the Journal of Open Inquiry in Behavioral Science, some details of which can be found here) in which 574 undergraduates, graduates, and PhD students were asked to allocate 100 points toward five different academic priorities, found that:

- Men allocated more points toward academic freedom and advancing knowledge than women, and women allocated more points toward social justice and emotional wellbeing than men.

A 2020 paper by Geher and colleagues, in which 140 academic faculty at colleges or universities in the United States completed the same point-allocation task described above, found that:

- Women allocated more points to social justice and emotional wellbeing than men, and consequently had fewer points to allocate to advancing knowledge, academic rigor, and academic freedom, although these latter three differences did not reach statistical significance.

A 2021 paper by Zhang and colleagues that coded 1,193 abstracts and surveyed 2,587 European researchers across three disciplines found that:

- Male researchers were more likely to specify scientific progress/the advancement of knowledge as the aim of their research; female researchers were more likely to specify societal progress/external usefulness as the aim of their research.

- Female scholars were more likely than their male counterparts to report that “creating a better society” inspires their work and to place higher value on research that has benefited society.

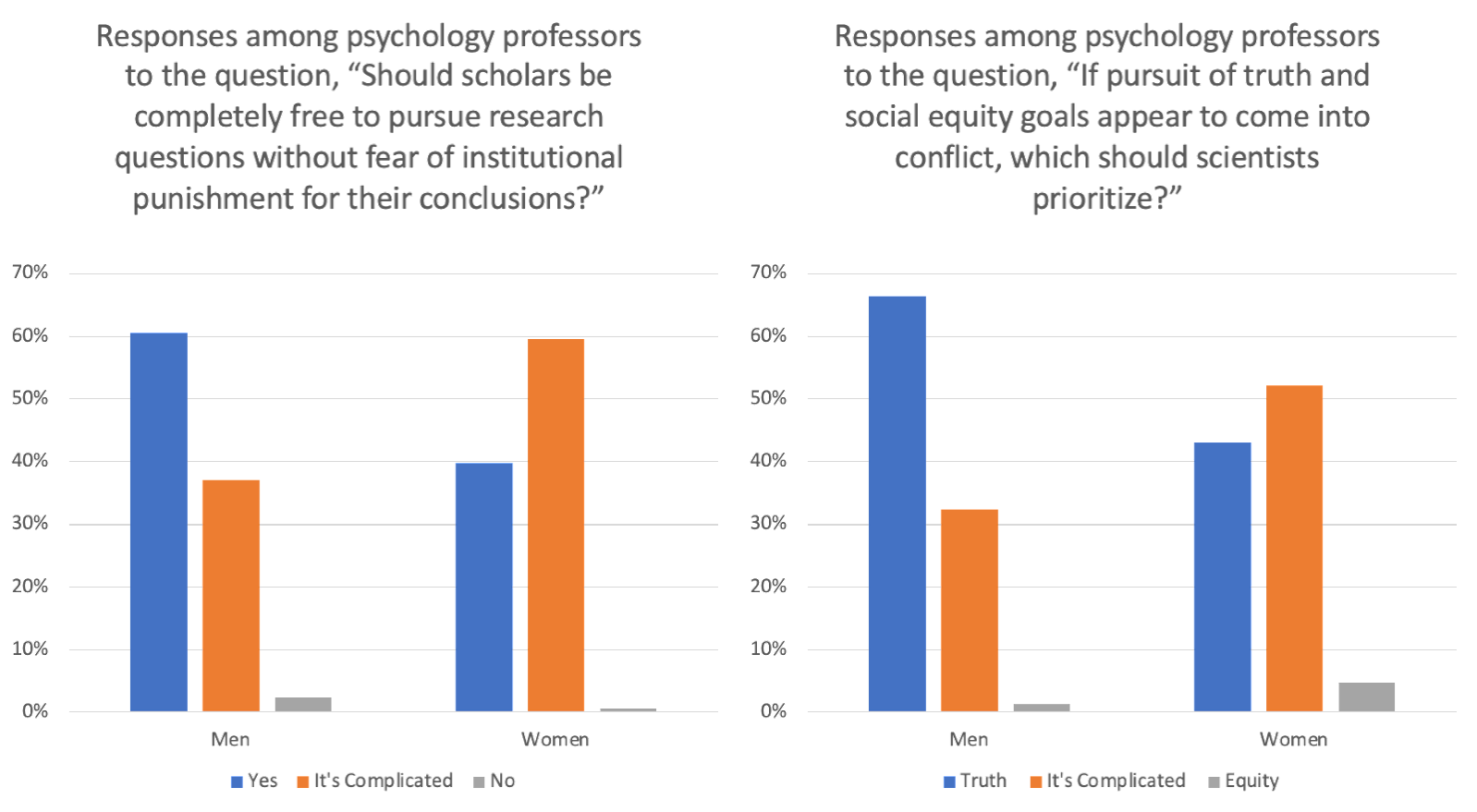

A 2021 survey one of us conducted with 468 psychology professors from over 100 top universities in the US (preprint in progress) found that:

- When asked whether scholars should be completely free to pursue research questions without fear of institutional punishment for their research conclusions, among men, the majority (60.5 percent) said “yes,” 37.0 percent said “it’s complicated,” and 2.5 percent said “no.” Among women, the majority (59.6 percent) said “it’s complicated,” 39.8 percent said “yes,” and 0.6 percent said “no.”

- When asked whether scientists should prioritize truth or social equity goals when the two conflict, among men, the majority (66.4 percent) prioritized truth, 32.4 percent said “it’s complicated,” and 1.3 percent prioritized social equity. Among women, the majority (52.1 percent) said “it’s complicated,” 43.0 percent prioritized truth, and 4.8 percent prioritized social equity.

The overall theme of these differences is that men are more committed than women to the pursuit of truth as the raison d’être of science, while women are more committed to various moral goals, such as equity, inclusion, and the protection of vulnerable groups. Consequently, men are more tolerant of controversial and potentially offensive scientific findings being pursued, disseminated, and discussed, and women are more willing to obstruct or suppress science perceived to be potentially harmful or offensive. Put more simply, men are relatively more interested in advancing what is empirically correct, and women are relatively more interested in advancing what is morally desirable.

Of course, it is often difficult to know what information is empirically correct and what information is most likely to improve society; therefore, such judgments will often be subjective and vulnerable to various biases and preferences. But in general, men appear to be less concerned about the potential moral consequences of empirical information than women. So, when a scholar forwards a potentially true but also potentially offensive claim or set of data, women will be more likely to strive to suppress it than men.

As is always the case when discussing group differences, these are averages. It is important to emphasize that plenty of women champion academic freedom and resist the claim that scholars should suppress research for moral reasons. Plenty of men, meanwhile, have embraced the claim that moral concerns should play an explicit role in the scientific process. However, on average, women are more willing to suppress science for moral reasons, and men are more willing to allow offensive or even potentially harmful ideas to be shared. As the population of academia shifts from one dominated by men to one that is more balanced or disproportionately female, support for including moral and harm concerns into the scientific and publishing process is likely to increase, and support for academic freedom is likely to decline.

This does not mean, of course, that women do not care about truth or that men do not care about social justice. It means that men and women weigh the relative importance of these values differently. In many cases, this will be irrelevant. But in those cases where truth and morality appear to conflict, men and women may adjudicate slightly differently. Because the social sciences are full of potentially morally relevant data about human nature and social disparities, this sex difference may be especially relevant to the future development of disciplines like anthropology, psychology, sociology, and other fields that study humans closely.

The Evolution of Sex Priorities and Preferences

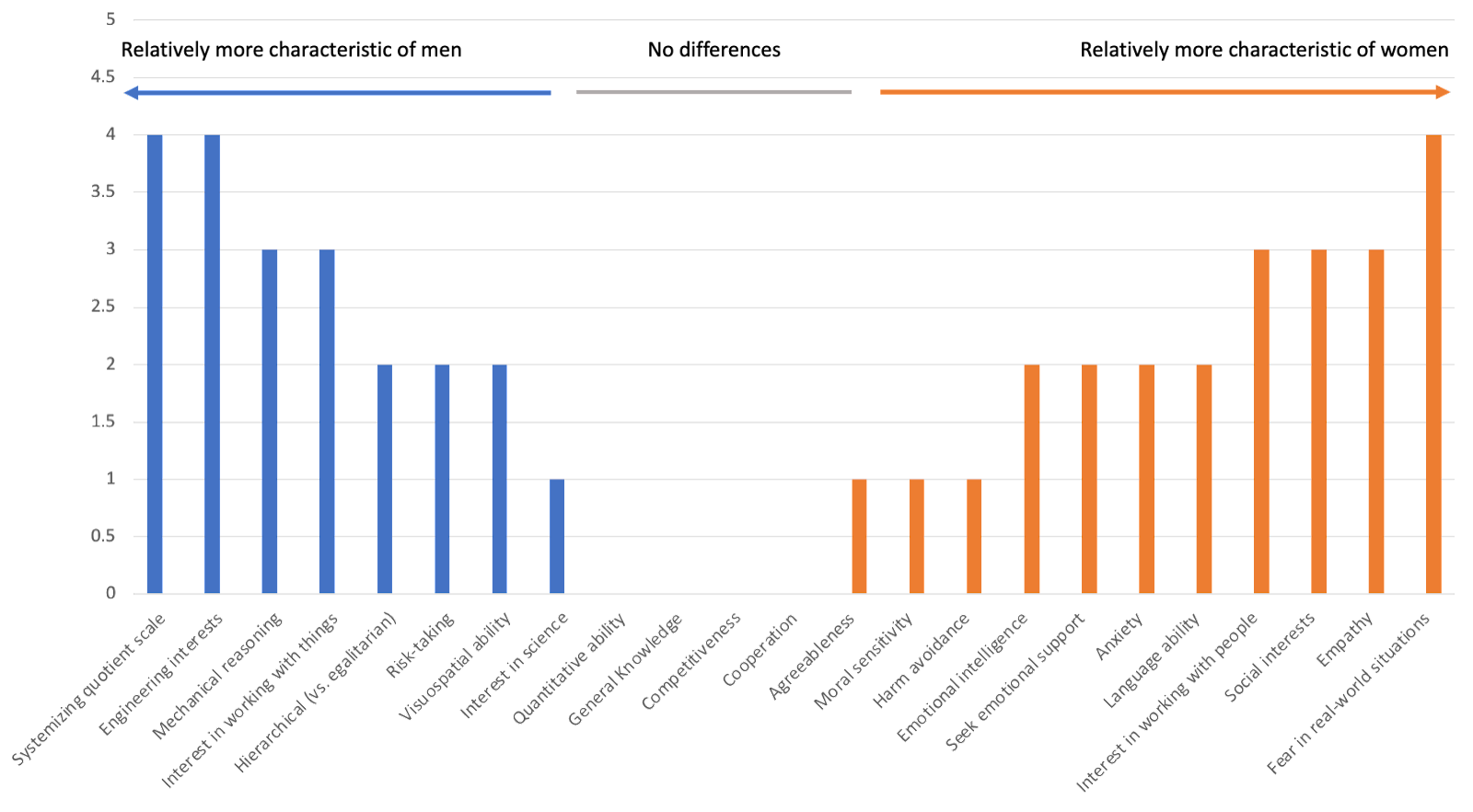

These sex differences in preferences and priorities for academia are consistent with a broader pattern of sex differences that have been extensively discussed and debated in the scholarly literature. Although the causes of these differences remain contested, we believe that evolutionary psychology (EP) provides the most fruitful framework for understanding them.

According to EP, the ultimate source of many sex differences is sexual selection, or the share of evolutionary selective pressures related specifically to reproduction. Sexual selection is ultimately governed by the level of parental investment of each sex, and sex differences are a result of differences in parental investment. In most mammalian species, including humans, females invest relatively more in offspring, whereas males invest relatively more in mating opportunities. Although this fundamental disparity has likely produced psychological differences in numerous domains (mating, for example), two are especially relevant: competition and interests.

Men compete more overtly than women for status; they are the larger and more physically aggressive sex (especially as that aggression becomes mortal), and they are more contest-oriented, vying against each other openly. Women, on the other hand, compete more covertly, using relatively safer and often more subtle methods. Men also compete mortally against other groups of men and have therefore evolved traits and tendencies that encourage the creation and coordination of large coalitions with status hierarchies. Women, on the other hand, prefer egalitarian social relations when in large groups and are not as predisposed as men to coordinating in large groups. Consequently, women prioritize equality more than men.

Perhaps the most dramatic way of expressing this suite of competition-related psychological differences is to describe men as “warriors” and women as “worriers”—a distinction Harvard’s Joyce Benenson coined in the title of her book about human sex differences. Although potentially provocative, such a heuristic is not without value. Women evolved, as Anne Campbell memorably put it, to survive so they could nurture their vulnerable offspring. Thus, women are more likely to experience self-protective emotions such as anxiety and fear, to be more harm- and risk-averse, and to have more empathy and desire to protect the vulnerable. Men, on the other hand, are more likely to take risks and to endorse hierarchy and support for conflict.

Men and women are reliably more interested in things and people, respectively. Relatedly, men have advantages in visuospatial reasoning and mechanical reasoning, and are more likely to desire system-oriented careers in engineering and programming than women. Women, on the other hand, have advantages in decoding non-verbal emotional cues and verbal fluency and are more likely to desire human-oriented careers in the arts and humanities. These differences, and others like them, are found in many cultures, arise early in development, and therefore likely explain the academic differences itemized above.

A protective impulse is likely to be alarmed by data or theories that appear to threaten egalitarian norms or vulnerable groups, and may produce an urge to suppress such scholarship. Since men are less empathic and sensitive to potential harms, and more interested in explaining things mechanically, they are less likely to be troubled by those data or theories and more motivated to publish apparently provocative but potentially illuminating research. This same pattern holds for campus speakers, professors, and classroom instruction: Women are, on average, more sensitive to potential moral threats than men.

From the perspective of EP, the sex-ratio-related changes in academia are neither arbitrary nor easily alterable. Men and women are psychologically different, on average, not because of patriarchy or social expectations, but because of evolved psychological mechanisms.

|

|

Men |

Women |

|

Social |

Open contest with hierarchical preferences |

Covert with egalitarian preferences |

|

Cognition |

Mechanical reasoning |

Verbal fluency |

|

Interests |

Things and systems |

People and relationships |

EP is not without critics, of course, and some scholars argue that psychological sex differences are in fact almost exclusively caused by cultural expectations and narratives. Perhaps not coincidentally, men and women assess the plausibility of evolutionary claims differently. Among psychology professors, men are more likely than women to agree that the sexes evolved different psychological tendencies. But even if one is skeptical of the evolutionary framework, men and women do display different preferences and priorities, so these analyses remain relevant. The changing sex ratios in academia have therefore led—and will continue to lead—to predictable changes in the institution because men and women have slightly different traits and tendencies.

Evidence for Changes in Academic Priorities

Academia has changed in various ways over the past few decades. By no means are all of these changes the direct or inevitable result of changing sex ratios. Nevertheless, some of the most drastic developments over the past 25 years share a common theme: They reflect the priorities of women. These include:

- The introduction of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) committees and offices on university campuses (e.g., in 1999 at Ohio State, in 2007 at SUNY, in 2016 at Amherst College), DEI programming and degrees, and a 34 percent increase in spending on DEI budgets from 2014–15 to 2018–19.

- The introduction of DEI Commitment Statements as a required part of job application materials for faculty members, which are more common in (more female-dominated) social science jobs than in (more male-dominated) STEM jobs.

- An increase over the past seven years in the number of academics targeted for sanction for their scholarship and teaching (and often, due to harm concerns about the content of their teaching or scholarship).

- The addition of extra-scientific moral concerns to the evaluation criteria for publications and retractions by journals such as Nature Human Behaviour and Nature Communications.

- The introduction of safe spaces and trigger warnings on college campuses.

- The requirement now made by large professional societies, such as the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, that presenters explain how their work advances equity and anti-racism, and the evaluation of presentations based on their ability to achieve these goals. (Anecdotally, this policy was instituted under a 13-member board, 11 of whom appear to be women. And this policy received public pushback from at least two members, both of whom are men.)

- Growing concerns about “coddling,” the “free speech crisis,” and increasing censorship and self-censorship on college campuses.

These changes reflect rising prioritization of egalitarianism (potentially at the expense of merit-based evaluations of science) and a desire to minimize potential harms and psychological distress (potentially at the expense of academic freedom). Both priorities are consistent with women’s evolved psychological preferences for egalitarianism and harm avoidance and stated higher prioritization of social justice and emotional wellbeing. In other words, these recent cultural trends in higher education are precisely what one would expect as women’s representation in academia grows.

One might argue that egalitarianism and psychological safety rarely come into conflict with academic freedom, pursuit of truth, and scientific rigor, and so as these former two priorities rise in importance, the latter three will not be affected. This may often be true. In many applied settings (such as medicine), for example, the entire purpose of the rigorous pursuit of truth is to discover interventions that improve human wellbeing, so truth goals and moral goals are almost perfectly aligned. But in other more theoretical areas of inquiry, the benefits of accurate information are not readily apparent but the potential dangers are obvious. These areas will likely be affected by sex-based priorities.

For example, research on psychological sex differences might appear to threaten egalitarianism and feminism because it suggests that some sex disparities are “natural.” It is easy to imagine that such research could be abused to undermine and restrict the rights of women—rights that were arduously won. So, this research may seem to be more risky than it is useful. In such cases, women are likely to be more cautious and have stronger desires to prevent such scholarship than men.

Of course, this pattern of change in academia is also confounded by ideology. Women are generally more left-leaning than men, and “equity and inclusion” has become a major moral concern on the political Left with which academia is increasingly dominated. In our own data, however, female sex continues to predict lower support for academic freedom and lower prioritization of truth after controlling for political allegiance.

Nevertheless, these changes may be co-occurring to create positive feedback loops. To wit: desire for social equity encourages women to pursue academia; a changing sex composition affects the ideological tilt and intellectual priorities of academia; and these new priorities further attract women and others with left-wing political priorities. But regardless of whether the equity or the estrogen came first, the growing percentage of women is likely to continue to influence the priorities of science and higher education.

The point here is not to lament or celebrate these changes, but simply to identify and try to understand them, and to note that they will lead to predictable downstream consequences. Institutions are not independent of the people who populate them, and altering the characteristics of those people will inevitably change them. Those who believe that the purpose—the lodestar—of science should be the pursuit of truth might find these trends worrisome. But it would be unethical and futile to attempt to roll back the enormous social gains women have made. The “men’s club” era of academia is over. A new and more female-oriented era is here for the foreseeable future.