Art and Culture

Napoleon in Rags

Jann Wenner’s attempt to set the record straight only confirms the unattractive picture painted by his critics.

A review of Like a Rolling Stone by Jann Wenner, 592 pages, Little, Brown (September 2022)

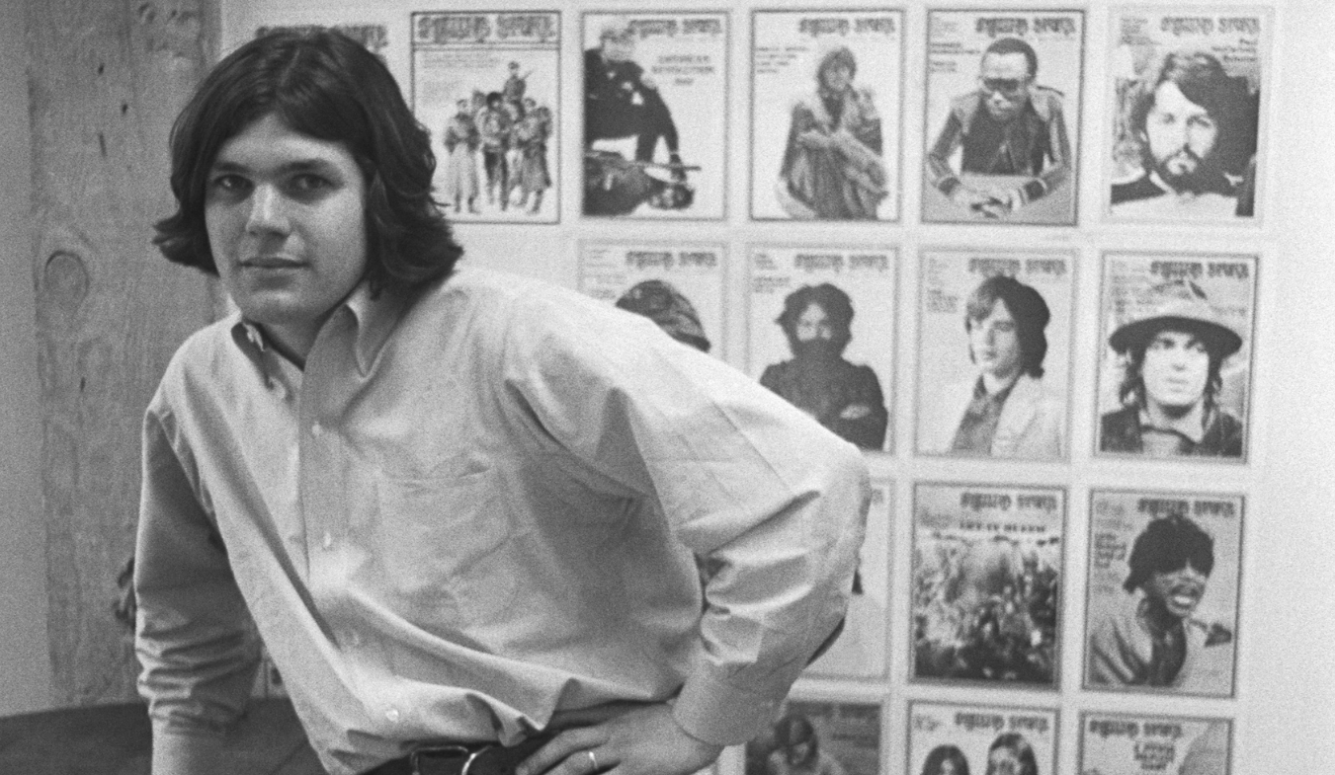

Over the past two decades, media magnate Jann Wenner has commissioned three authorized biographies. Unfortunately, each portrayed him as such a loathsome creature that he had two of them shut down and unsuccessfully attempted to stop the publication of the third, Sticky Fingers: The Life and Times of Jann Wenner and Rolling Stone Magazine (2017). Enraged that three separate biographers had portrayed him as a cruel, greedy, and shallow shyster, Wenner has set out to show the world that he is, in fact, a decent human being with his memoir, Like a Rolling Stone (September, 2022). He has failed.

The book begins promisingly in mid-2019 with an ageing Wenner in the offices of Rolling Stone bidding farewell to the magazine he co-founded more than a half-century before. He is brash but reflective as he looks back on the impressive legacy of his publication. A guided walk through the detritus of a dying empire alludes to its former glories, like exploring the streets of Rome, guided by Julius Caesar himself. Wenner briefly admits some regrets and teases a sense of bitterness as he passes the reins to his son, Gus (short for the rather apt Augustus).

We are about to embark, it seems, on an introspective journey, but soon we are back in Wenner’s childhood and the bragging begins. This is, after all, a rock ’n’ roll memoir—the sort that elevates its already lionised hero, allowing him to exaggerate his accomplishments, boast about his bad behaviour, strike back at his critics, and stroke his own unwieldy ego. He was a “problem child,” he tells us; a rebel so difficult that his parents packed him off to boarding school. In sixth grade, he decided he would be a great publisher and editor, and set off on his journey, publishing his own minor newspapers.

This troublesome but precocious kid is soon seduced by rock music and his future unfolds before him. At first, Wenner is enthralled by The Beatles, about whom he has this to say:

We didn’t realize it then, but they alleviated the heaviness and cynicism of a society that had killed its beautiful young president and had peeled back the mask on its racism. The Beatles were a last flourish of innocence and joy before the war in Vietnam came home.

Right out of the gate, it is clear that Wenner is not just a music fan but fascinated by rock stars and stardom. “The rap against Wenner,” William McKeen writes in Outlaw Journalist: The Life and Times of Hunter S. Thompson, “was that he was the ultimate groupie, that he had started Rolling Stone as a way for him to meet the Beatles.” In Sticky Fingers, Joe Hagan agrees, calling him a “fanboy” and “starfucker,” whose adulation managed to embarrass John Lennon. Robert Anson, in Gone Crazy and Back: The Rise and Fall of the Rolling Stone Generation, said much the same: “Wenner had started Rolling Stone simply so he could meet his gods.”

Wenner, of course, frames his motivations quite differently. Throughout his book, he claims that his political views were the prime motivator of almost all his actions. Before Rolling Stone, he was active in the Berkeley Free Speech Movement, and from his first days as a publisher, he used his magazine to further progressive causes guided by noble liberal beliefs. Others have disagreed, suggesting that Wenner was interested in fame, power, and money, and only moved into politics when it became profitable to do so. “His relationship to radical politics had always been a cautious one,” Hagan writes. Wenner was not nearly as eager to push Rolling Stone into politics as he now claims and had always been quick to run out on protests whenever it looked like the police might show up.

That Wenner had a deep love of rock music and a passion for progressive politics is evident from his book. Nonetheless, these were underpinned by a desperation for attention and a desire for power. The most irritating aspect of the book is Wenner’s shameless name-dropping. Of the 185,000 words in this hefty volume, it sometimes feels like half are the names of famous friends. Of course, many of these names are included for good reason—Wenner was, after all, the publisher of an important rock magazine and did indeed meet with numerous celebrities. But he is extremely keen to emphasise just how much musicians and movie stars loved him and how close he was to them. And some of his anecdotes are rather dubious—a teenage car ride with Neal Cassady, for example, or his arrival in London as a young man with no connections where he bumped into Brian Jones on the street.

The ceaseless name-dropping isn’t just gauche but it also frequently produces a disjointed narrative. He jumps from memory to memory, apparently determined to include every moment of personal, cultural, or political significance, without bothering to connect one passage to the next. This is particularly jarring when traumatic events are awkwardly juxtaposed with humorous ones. And notwithstanding its vast length, the book appears to have been brutally cut in places, so that certain references don’t make sense. The dust-jacket may describe Wenner as “the greatest editor of his generation” but you wouldn’t know it from reading his memoir.

It is tempting to forgive such problems amid the general exuberance of your average rock ’n’ roll autobiography. These people are, after all, professional bad boys, so being rude, boastful, and semi-literate comes with the territory. But one expects more from the man who made his millions as the publisher of a rock magazine, and who positions himself as a key figure in countless works of art and journalism from the late 20th and early 21st centuries. This is something Wenner badly wants his reader to appreciate.

Again and again, we are reminded of Wenner’s prescience and genius. Every accomplishment at Rolling Stone, it seems, is directly attributable to him. Each award-winning article was the result of his advice and each iconic photograph was his idea. You get the impression that he taught Annie Leibovitz how to take a picture and Joe Eszterhas how to write. He applauds himself for every triumph, regardless of how much input he actually had, and this extends not only to the content of Rolling Stone, but to songs and books by his friends. Whenever he claims to have had a word in an artist’s ear, their next hit is practically Wenner’s own work. No one, it seems, would have achieved a modicum of success without his guidance.

Still, it bears repeating that he was a talented man and that he did provide gifted people with a platform to pursue greatness. Wenner took risks on young writers and encouraged them to make great creative leaps. Most former Rolling Stone writers and editors, despite their contempt for the man, freely admit that he was in some ways a brilliant editor. But as he details the story of his empire building, Wenner feels the need to remind us of his own genius constantly, tossing off lines that begin, “As talented and passionate as I was…” When he tires of flexing his own ego, he uses quotes from his famous friends to highlight his brilliance. There are dozens of these inserted awkwardly throughout the book, from Linda McCartney to Bono, and even chunks of speeches given at award ceremonies, where rock stars fawn over him. The most embarrassing of these is Mick Jagger’s declaration that, “Jann almost single-handedly pioneered the idea of popular music and of rock and roll in particular as a vibrant art form.” Later, he tells us that Dylan and Jagger fought over who inspired him to name his magazine. The superfan, it now seems, is adored by his own idols.

More troubling than the poor writing and editing, the endless name-dropping, the eagerness to take credit for the work of others, and the casual boasting is that Wenner generally seems to have been an awful human being. This is made clear in Hagan’s book and almost any book or article about Rolling Stone, as well as in most interviews with the magazine’s writers and editors or anyone who spent any time at its offices. “He loved to humiliate people” is a representative comment. Wenner was famously sadistic, constantly belittling staff members and firing them over trivial matters. An explosive and impulsive temperament was no doubt aggravated by his cocaine habit (which he makes no effort to disguise in his book). One might reasonably have expected him, in his old age, to look back on these temper tantrums with some remorse, but instead he sneers and laughs, recalling the superiority he felt. Explaining his desire to cover Bob Dylan’s receipt of an honorary degree, Wenner writes:

The managing editor thought it was trivial, so I told him it was time for him to hit the road. Which he did. I got rid of his loyalists. … I decided I would be the new editor.

For all the people he recalls casually firing, there are others he omits. In Sticky Fingers, we learn that Wenner once bought an expensive lighter, accidentally scratched it, and then fired his secretary in a fit of rage when she hesitated to send it back and pretend that it had arrived damaged. She had exercised “bad judgement,” Wenner told Hagan.

In his memoir, he quotes the following line from a New York magazine article: “Jann Wenner desperately wants to be famous; he’s erratic … humiliates staffs; eats off other people’s plates…” Few who knew Wenner would disagree with this description, the truth of which is made abundantly clear in his own writing. Yet, somehow, he believes it to be an outrageous calumny written by a journalist who was self-evidently jealous of his success and his famous friends.

Wenner’s astounding arrogance has left him so out of touch and bereft of self-awareness that he sometimes appears sociopathic. He seems to have no capacity for empathy. Watching his children being born via caesarean section, he casually describes his wife’s organs being lifted from her body, “spellbound.” Watching another of his children born this way, he simply remarks, “It didn’t bother me.” Later, he physically recoils from his dying mother, admonishing her for being “self-aggrandizing.” His hypocrisy beggars belief. He goes on to say he is uncomfortable with her coming out as a lesbian late in life, even though he hid his own homosexuality until he’d fathered three children with his wife. In New York City on 9/11, he describes watching the unfolding horror while he eats his breakfast. “I wasn’t thinking of people jumping out of windows,” he writes—instead, he thinks about wasted money and ponders how it will affect the next issue of Rolling Stone.

Unsurprisingly, a lot of the book is devoted to the career of Hunter S. Thompson. Wenner was, after all, a major part of Thompson’s life and the two men knew each other from 1970 until Thompson’s 2005 suicide. It is fair to say that much of Thompson’s success was due to Wenner taking a huge gamble on him, providing advice and support, and tolerating numerous missed deadlines and outbursts. It was a marriage of convenience, of mutual respect at times, but they were both difficult individuals—egomaniacs, cokeheads, bullies—and constantly at each other’s throats.

So how does Wenner portray his old friend? The chapters about Thompson’s suicide and funeral are certainly the most engaging and coherent sections of the book. However, there are numerous problems with how Wenner remembers their relationship. In addition to multiple factual errors, Wenner has re-written their shared history to make himself look better. One of the most famous stories about Thompson and Wenner is that when the former flew to Saigon to cover the city’s fall to the North Vietnamese, Wenner fired him and voided his life insurance whilst Thompson was en route. Here is Wenner’s version of events:

After he got back, he started telling people and his college-lecture audiences that I had canceled his health insurance while he was in “the middle of a goddamn war zone.” It got a good laugh but the story was patently false. I shrugged it off at first, but as he kept spreading it, I realized that people believed him. I told him to stop or I’d start telling the true story. He stopped, but that allegation lingered.

The truth is that Wenner attempted to fire Thompson but that his staff, accustomed to his fits of rage, simply decided not to file the paperwork. Wenner claims that this was a joke between the two men and that Thompson only made the claim to get laughs, but that isn’t true either. Thompson’s letters and unpublished writings attest to the fact that he was furious about Wenner’s attempt to fire him.

During a different passage about Thompson, Wenner accidentally offers another glimpse of how greedy and two-faced he could be. In 1975, cartoonist Garry Trudeau turned Thompson into Uncle Duke for his Doonesbury comic, mocking him in public and stealing his intellectual property. Thompson was livid. He eventually became paranoid that someone in his inner circle was feeding Trudeau private stories. Of this, Wenner writes:

I told Hunter he could and should stop “Uncle Duke,” that it was his literary property, his soul, his livelihood. But Hunter did nothing. … I never said anything to Garry about it, other than to make a few casual digs, and when he asked about doing a Rolling Stone cover of Uncle Duke, who in the strip had become the U.S. ambassador to Samoa, I went along with it.

Putting Uncle Duke on the cover of his magazine was a pretty gross violation of their personal and professional relationship, yet Wenner expresses no regret about betraying his friend for financial gain (Wenner’s inability to be self-critical is one of the book’s recurring themes). Much later, after two lengthy and touching chapters about Thompson’s death, Wenner makes this dubious claim:

For the record, Hunter and I never had a fight with each other, not once. I’m sure he called me a “cheap and greedy waterhead,” and I called him “washed up and brain-dead,” but he was always carrying on about people … We were having fun, lots of it.

This is not supported by the evidence. Thompson was forever bitching about Wenner to journalists and friends—I have news clippings, letters, faxes, and transcripts of phone conversations and it’s obvious that Thompson’s grievances were perfectly serious. In 1975, for example, he contacted the Chicago Tribune in an effort to make his complaints public. The reporter was cautious and admitted that he would not print most of what Thompson said, but summarised: “Basically, Thompson thinks he has been betrayed in several ways by the magazine, and is upset enough about it to want to dissociate himself from Rolling Stone.”

The following year, Thompson’s lawyer sent an article to Esquire that he insisted be published under the name “Deep Thrust.” Titled “Citizen Wenner,” it was clearly written by Thompson and his attorney. In it, the pseudonymous author claimed that all of Rolling Stone’s post-1970 success is attributable to Thompson’s ideas and denounced Wenner as a “prick.” He continued:

[Wenner] has ruptured relations with each and every key person who helped put Rolling Stone on the map. Even Ralph Gleason who put up most of the original capital was disgusted by Wenner’s arbitrary tyranny and he made no bones about saying so. He would have puked if he had seen the tribute to him in those pages after his death last summer and heard Wenner claim he was suffering from an emotional breakdown because of the loss. “He was a father to me,” moaned the bereaved Baron (sic) over and over again. … Sure he was Jann and of course no boy is a man until he has kicked his father in the balls.

This incident and countless others prove the obvious: That the relationship between Thompson and Wenner was frequently far more acrimonious than Wenner admits. But the book is filled with brazen falsehoods like this one, not to mention evidence of the author’s willingness to hurt his friends when he found it profitable or otherwise expedient to do so.

Sticky Fingers almost certainly offers a more accurate view of Wenner and his business than this book, as does the slightly dated Gone Crazy and Back Again. But even readers unfamiliar with Wenner and the extent to which he misrepresents history will find enough in his transparently self-serving memoir to earn their distrust. He harps endlessly on his lofty values, yet shows himself violating them at every turn. Does he express any remorse for spiking stories to appease advertisers? He does not. This money, he tells us with evident satisfaction, was his pass to private jets and mega-yachts and holidays with the Kennedys in the most exclusive resorts. It was his entry into the highest of high societies.

Wenner may claim that his mission was to turn rock ’n’ roll into art and to speak truth to power, but towards the end of the book we see just how much power he has amassed. He tells us about taking Al Gore’s seat in Air Force Two, riding with Bill Clinton in Air Force One, and about Barack Obama dropping by to visit him, not the other way round. “I felt like I was sitting with an equal,” he blithely announces as he recounts chit-chatting with the President of the United States. At no point does he ever seem to be aware that he is now a part of the establishment his magazine initially stood against.

As so many autobiographies do, this one slides to a close with tales of its author’s ailing health. He is introduced in the first chapter leaning on two walking sticks, and towards the end of the book we learn of a litany of health problems. I even began to feel a little sorry for him, in spite of everything. His decline mirrors that of his magazine, which struggled badly with the arrival of the Internet and then almost stumbled to its demise with the UVA rape scandal in 2014—a catastrophic failure of investigative journalism. Yet even here, Wenner is defiant: “I thought it was terrific and authorized publishing it. It didn’t occur to me to remind anyone about fact-checking and secondary sources. We trusted the writer.” Another missed opportunity to admit fault—Wenner subtly shifts the blame with his use of the word “remind.”

In the paragraphs that follow, Wenner blames a lack of money for fact-checking, the university for hindering the investigation, and even points out that other magazines and newspapers had made similar mistakes. He is indignant that Rolling Stone had to pay damages, despite the harm caused by its fraudulent essay. He then moves quickly to claim he was the first to see the danger of Donald Trump, and tells us how he sold Rolling Stone to become even richer.

At the end of a long and successful career, it must be tempting to use your memoirs to settle scores with those who criticised you along the way—and Jann Wenner has no shortage of critics. But such a project also offers a rare opportunity for self-reflection, contrition, and gratitude, and an occasion for humility and acknowledgement of good fortune. Wenner has taken precisely the opposite approach. He wants to remind us, blowing as hard as he can and as often as possible, that he is special. He is rich and powerful and walks among the greats as their equal. In the final pages, he notes that Keith Richards’s autobiography, Life, was his inspiration. It is a telling admission. Wenner wants to be perceived as another rock star. But it is one thing to read about the gritty life of a talented musician and quite another to spend nearly 600 pages in the company of a bitter millionaire attempting to lay claim to the achievements of everyone around him.